Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $DXCM at the time of publication, and hedging with a basket of derivatives that may include securities named in this article. Positions may change at any time. Based upon our reporting, the claims in this article are being further investigated by the law firm of Wisner Baum LLP. You may contact them regarding any rights you may have to a refund for your purchases of the products discussed in the article. We’ve also petitioned the FDA to intervene and shared this investigation with a senior HHS official. Doctors or others wishing to support the petition may do so via ideas@hntrbrk.com. See full disclosures below.

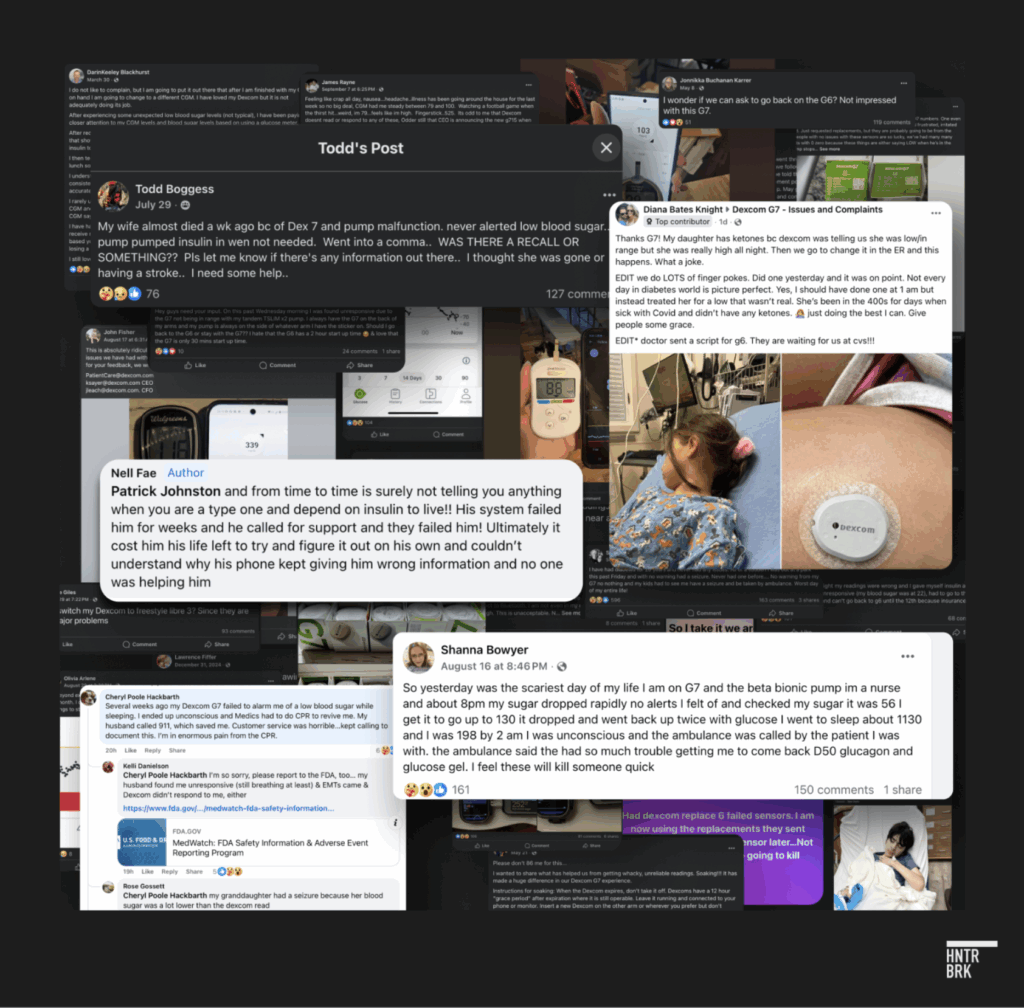

- G7 users have been hospitalized and died: Billy Sosbe lost his life in June after his G7 gave him incorrect glucose readings. Diana Bates Knight’s six-year-old daughter was rushed to the ER when her G7 misread her blood sugar by hundreds of points. Bob Hawkinson passed out behind the wheel when his G7 failed to alert him to dangerously low blood sugar. These aren’t isolated incidents. More than a dozen other G7 users interviewed by Hunterbrook said they felt betrayed by a technology that had once been life-changing. According to a law firm investigating the G7 following a recall and FDA warning letter, at least 60 people claim to have been hospitalized and multiple others allege death connected to G7 issues. A Facebook group for G7 problems exploded to more than 58,000 members in just over one year.

- Dexcom staff say corporate culture put margins over safety, eroding trust in the brand: Former employees described safety concerns in a rush to launch the G7 to compete with Abbott. Leadership of the team responsible for a component flagged by the FDA had inadequate credentials with a “very low” technical level according to a former scientist. The former senior director of manufacturing at the company’s critical Mesa, Arizona, plant said “Dexcom definitely dropped the ball” and “the arrogance of Dexcom is really what needed to be reset.” Another former executive said Dexcom compromised the product trying to “hold on to large revenue margins.” Multiple former employees told Hunterbrook the G7’s problems are symptomatic of a deeper struggle: an innovative company floundering to keep alive a growth story demanded by Wall Street amid a series of headwinds.

- Doctors raise alarms: Hunterbrook spoke with endocrinologists across the country. While all reported imperfections with continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) generally, several highlighted issues with the G7 in particular. They noted disproportionate sensor inaccuracies, repeated device failures, connectivity issues, and problems with the adhesive. Two said when they spoke with Dexcom representatives, the company expressed surprise or “didn’t know anything,” a phenomenon one doctor said was tantamount to “gaslighting.” Others told Hunterbrook they have stopped putting patients on the G7 altogether.

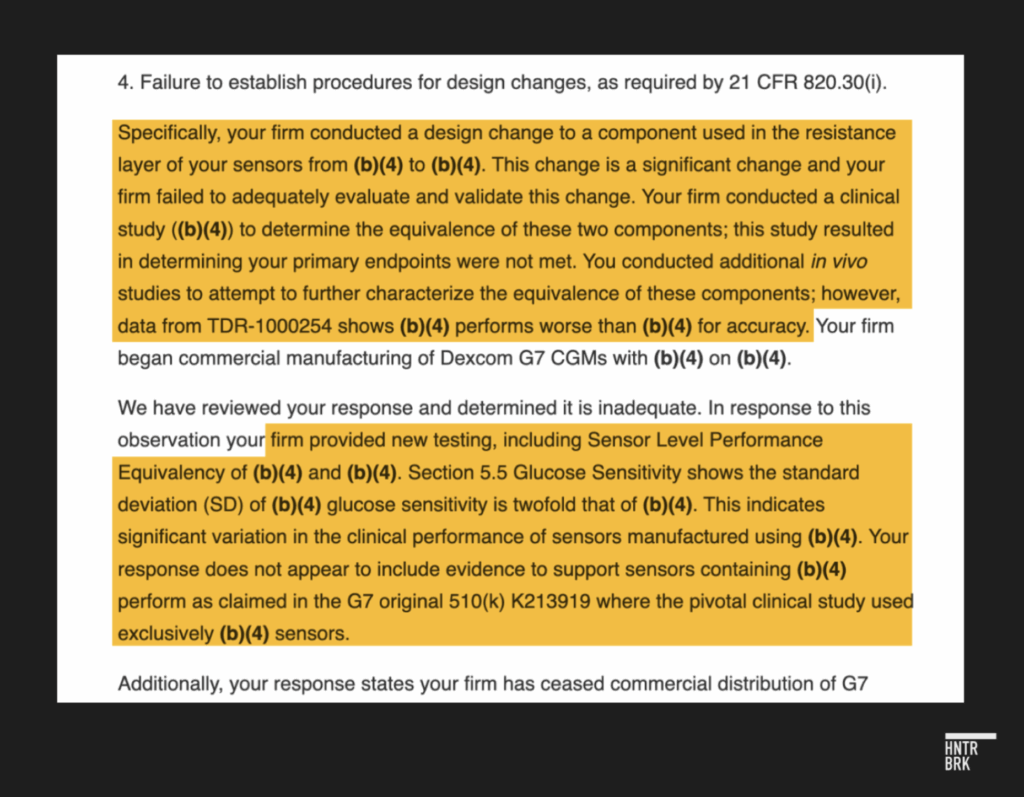

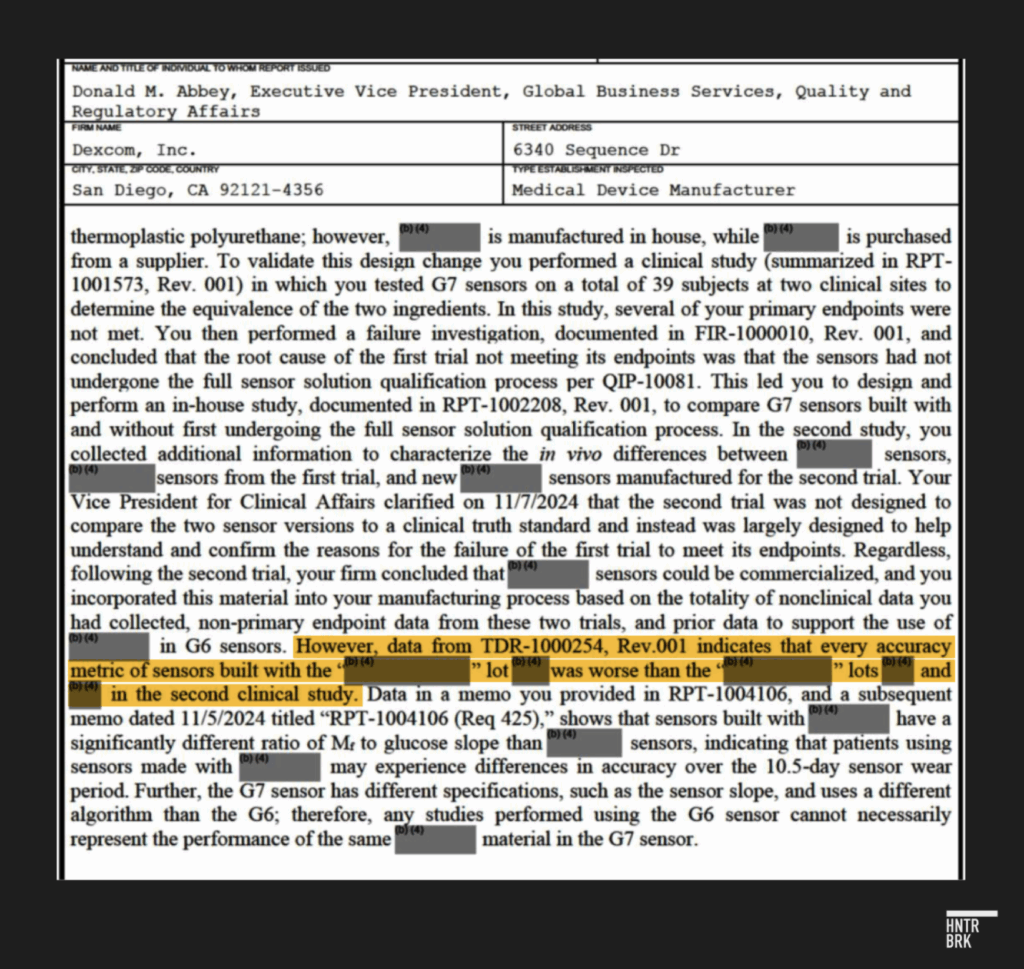

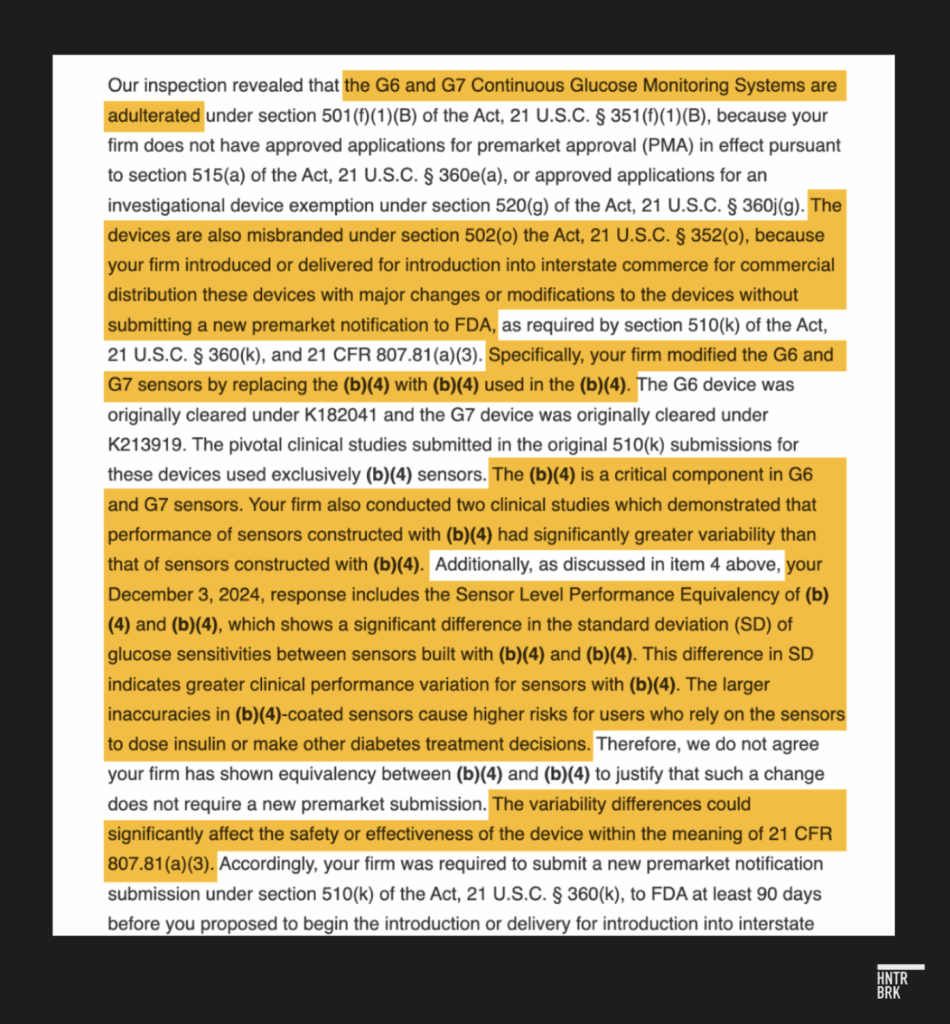

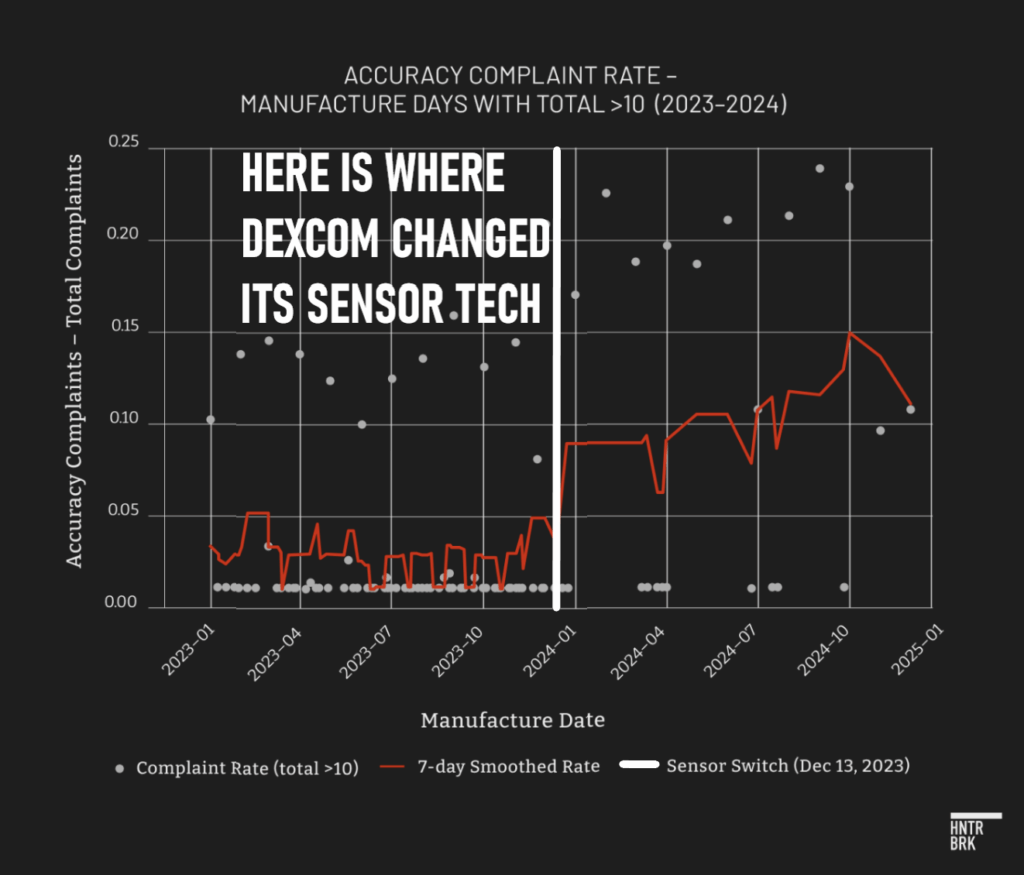

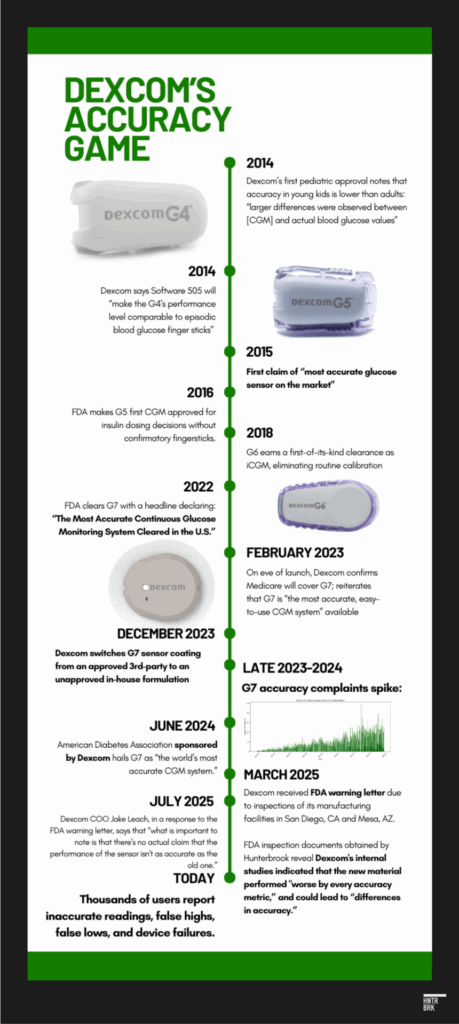

- Dexcom incorporated materials into the G7 that it knew were worse by “every accuracy metric,” according to FDA documents: In December 2023, Dexcom switched the coating of G7 sensors from an outsourced material to an in-house formulation. FDA inspection documents obtained by Hunterbrook show Dexcom’s internal studies demonstrated the new material could lead to “differences in accuracy” that may affect insulin dosing. Despite its own tests failing to show equivalence with the original component, Dexcom sold the product anyway — without proper regulatory clearance. The FDA cited Dexcom with a violation for making this unauthorized change to a “critical raw ingredient” and declared the devices “adulterated.” Complaints about the G7’s accuracy were far greater for devices manufactured after Dexcom changed the material in December 2023, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of FDA data.

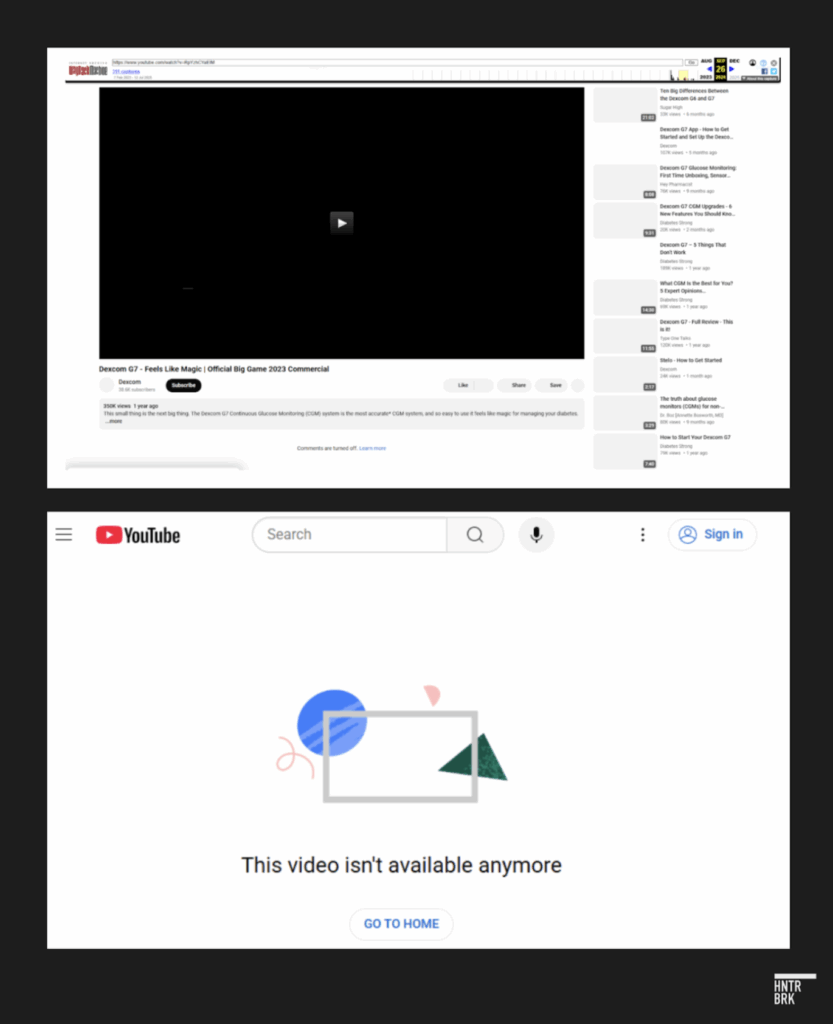

- Despite “Most Accurate CGM” marketing, the G7 has more FDA complaints for accuracy than competitors: Hunterbrook analyzed the FDA adverse event reports for Dexcom’s G6 and G7 versus Abbott’s competitive Libre 3 line. Dexcom generates 22% more accuracy complaints than expected based on a Hunterbrook estimate of market share, while Abbott logs 68% fewer. An Abbott-funded study demonstrated that its Libre 3 beat Dexcom’s G7 on accuracy. Dexcom’s multimillion-dollar 2023 Super Bowl ad starring Nick Jonas marketing the G7 as the “most accurate CGM,” requiring “no fingersticks,” disappeared from the company’s YouTube channel.

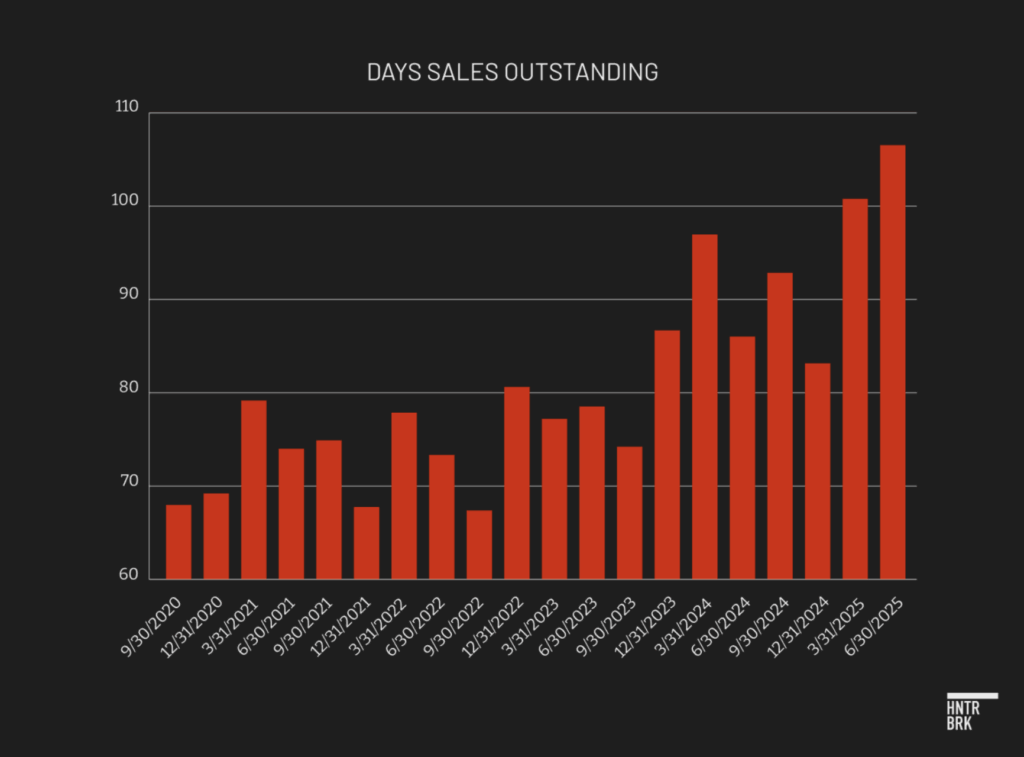

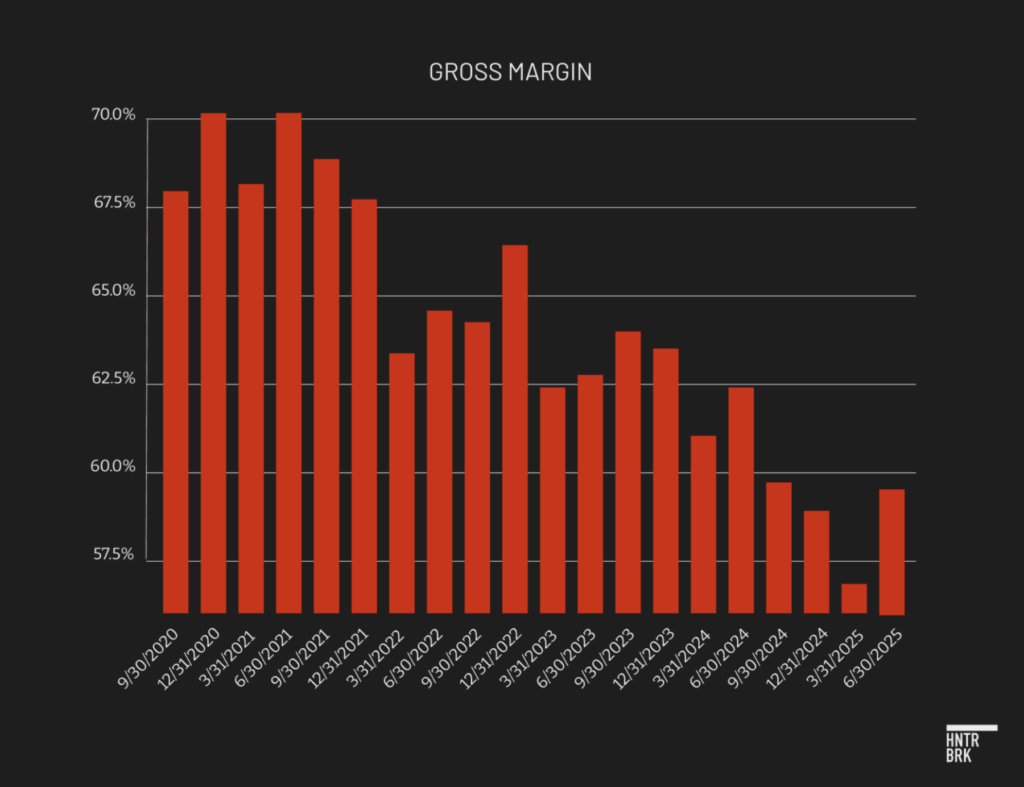

- Dexcom only beat second-quarter earnings with aggressive accounting — setting up another potential downside surprise like 2Q24: Accounting tactics nudged Dexcom over the bar of earnings expectations in its last quarterly report, according to forensic accounting. Dexcom appears to be pulling forward revenue, with days sales outstanding ballooning past 100 days, compared to a normal range of between 30 and 90 days. Work-in-process inventory doubled from historical norms, possibly concealing expenses. The last time Dexcom was exposed for similar accounting issues, its stock then fell 40% when it reported disappointing second-quarter earnings in 2024. Bank analysts are seeking for Dexcom to grow over 15% annually, despite cutting costs to keep well over 60% margins (aka: demanding growth while reducing expenses). This growth story relies on the G7 penetrating markets currently led by Dexcom’s competitor Abbott, which appears to have a more reliable, cheaper CGM. Abbott recently claimed it will “100%” take users from Dexcom.

- Market share threatened: Abbott is developing a next-gen device to monitor both glucose and ketones, a major upgrade. Dexcom’s Stelo CGM (an over-the-counter product marketed to nondiabetics and people who don’t need insulin) missed launch expectations. The Stelo drew so many complaints that an unrelated software company also named Stelo sued Dexcom claiming brand damage. GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic may slow the previously inexorable rise of Type 2 diabetes, Dexcom’s growth market. Meanwhile, proposed Medicare changes would subject CGMs to a competitive bidding process, meaning Medicare might pay Dexcom less for CGMs, its core product.

- Executive exodus: Several top executives left within a year including the CEO, VP of global operations, chief commercial officer, and head of engineering, according to SEC filings, LinkedIn profiles, and deleted Dexcom website pages. Longtime CEO Kevin Sayer was supposed to stay through the end of 2025 and then become executive chairman, but unexpectedly left this week, citing medical leave. The new CEO is the son-in-law of Dexcom’s former CEO.

- Dexcom did not reply to repeated requests for comment: Hunterbrook’s reporting indicates that amid declining market growth and increased competition, Dexcom cut corners, compromised safety, and manipulated financials while its execs were selling their own shares and jumping ship. Many users of its flagship device suffer the consequences. Dexcom apparently had nothing to say in response to Hunterbrook’s findings, but at an investor conference on September 10, management downplayed quality rumors as “minor things.” This mirrors a dismissal of patient concerns by Dexcom’s new CEO earlier this year. When asked about accuracy issues with the G7, he said, “Things happen.”

Billy Sosbe was inclined to be skeptical, his sisters recalled, not the person you’d expect to jump on the newest tech trends.

But the Wisconsin car salesman chose to entrust the management of his Type 1 diabetes to a Dexcom G7 continuous glucose monitor, or CGM. Like millions of other people with diabetes, Sosbe bought into Dexcom’s promise: no more painful and messy finger pricks.

Instead, Sosbe could rely on a constant stream of data on his blood sugar by wearing a coin-sized disposable patch.

Dexcom — a CGM pioneer — launched the G7 with a Super Bowl ad featuring Nick Jonas. Sosbe’s doctor recommended it. Sosbe suffered from a few health conditions, and the idea was that the G7 could help him better manage his diabetes.

In June, one of Sosbe’s sisters found him dead. He was curled on his bed with foam at his mouth.

A G7 was still stuck to his arm.

“He trusted it and he’s dead,” his sister, Janell Drake, told Hunterbrook Media.

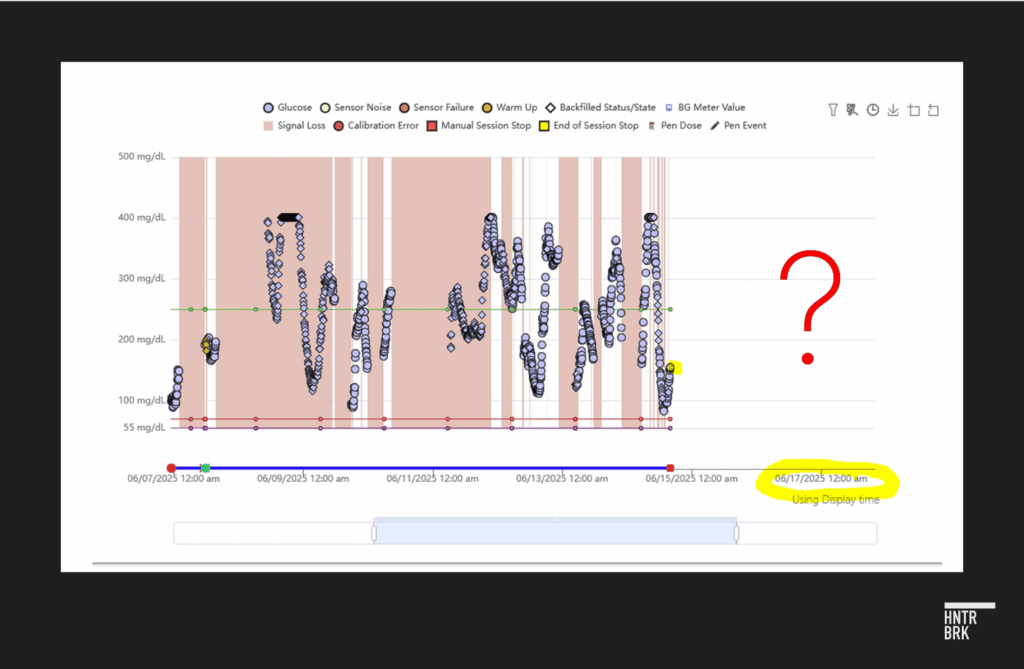

Drake said she believes her brother took the wrong doses of insulin for months based on inaccurate readings from his G7. Her conclusion appears to be supported by data that Dexcom shared with her after Sosbe died, showing “severe signal loss” on his device for months leading up to his death. Readings seem to have stopped entirely two days before he passed.

In Drake’s view, Dexcom had information about issues with his G7 prior to Sosbe’s death — issues she wishes they had flagged.

“Nobody batted an eye at it,” she said.

The G7 was supposed to be the best product Dexcom had ever made. Much smaller. Faster to start up. The “most accurate CGM,” the company claimed, after years of hyping its products as making obsolete the old school fingersticks diabetics had relied on for decades. (A sample quote from an ad: “Drones deliver packages and people with diabetes are still pricking their fingers — what?!”)

For Sosbe and other diabetics wagering their health on that claim, the G7 has proven catastrophically unreliable. More than a dozen other G7 users interviewed by Hunterbrook said they felt betrayed by a technology that had once been life-changing.

Bob Hawkinson harbors powerful childhood memories of glass syringes boiled by his mother, with hand-sharpened needles to deliver the insulin that has kept him alive since infancy. CGMs meant he could take a walk without pricking his finger.

Then, one day, he was revived by bystanders forcing grape juice down his throat, he told Hunterbrook, after he passed out while driving.

His G7 hadn’t alerted him to dangerously low blood sugar levels.

CGMs meant Courtney Duffy could avoid an awkward conversation with a date about how they might handle the sight of blood. But one morning, she told Hunterbrook, she was found unresponsive by her roommate and woke up in an ambulance to the sound of EMTs yelling, rushing to save her life when the G7 failed to connect to her automated insulin pump.

CGMs meant Diana Bates Knight could better manage her six-year-old daughter’s Type 1 diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition where the body mistakes insulin-producing cells in the pancreas as pathogenic invaders and destroys them, leaving people unable to make insulin naturally. People with Type 2 generally can produce their own insulin, but they don’t make enough, the body can’t properly use it, or both. Everyone with Type 1 has to take insulin; not all people with Type 2 do. But the G7 misread her daughter’s glucose level by hundreds of points, Knight told Hunterbrook, sending the child to the emergency room with a life-threatening complication.

“He trusted it and he’s dead.”

– Sister of William Harold Sosbe

The law firm Morgan & Morgan, which has opened an investigation into the device, told Hunterbrook that more than 400 people have recently contacted them related to Dexcom. Of those, nearly 60 allege that users were hospitalized, and several claims involve a user’s death.

The hospitalizations and deaths expose the depth of the crisis consuming Dexcom, a trailblazer in diabetes care since its founding in 1999.

Amid pressure from competitors, Dexcom cut corners and put an unreliable product on people who need it to survive, according to Hunterbrook’s months-long investigation.

Hunterbrook reporters spoke to dozens of users, former employees, and healthcare experts; analyzed data on complaints to the FDA relative to clinical trial results and competitor complaints; tested a Dexcom device on the arm of a reporter; attended a diabetes conference; and obtained access to FDA inspection records for Dexcom’s facilities via the Freedom of Information Act. What the FDA found in these inspections led the agency to send Dexcom a warning letter in March 2025.

Former employees described a toxic culture that put profit above quality — an environment that may explain the company’s rushed approach to bringing the G7 to market to compete with Abbott, a healthcare giant that recently told investors it will “100%” take market share from Dexcom.

While Dexcom awaited FDA review of the G7, Abbott’s competing Freestyle Libre 3 won clearance in May 2022 and launched later that year. Dexcom resubmitted its G7 application to the FDA in mid-2022, with software revisions based on FDA feedback, according to Dexcom. Its next-gen product, currently in development, will include ketone monitoring, an important upgrade that Dexcom has reportedly not committed to providing in its proposed G8. Ketones form when the body burns fat instead of glucose for energy. They’re another key biometric for diabetes management, as high levels turn blood acidic and can be life-threatening for people with Type 1 Diabetes.

“Dexcom is trying to hold on to large revenue margins,” a former regional account executive told Hunterbrook. “And whenever you try and do that, you are going to run into an area where you compromise the product, and I think they’ve done that.”

A former senior scientist noted the electrochemistry and membrane teams were led by managers with weak scientific credentials.

“The technical level was very low,” they said.

Sure enough, Dexcom replaced a critical ingredient in the G7’s membrane with a substitute that had performed worse by “every accuracy metric” in the company’s own testing, a November 2024 FDA document shows. It’s unclear how long Dexcom sold the less accurate device before telling the FDA it ceased “commercial distribution” of the “adulterated” G7. FDA records show that (1) Dexcom began manufacturing the devices with this change on December 13, 2023; (2) the FDA first cited Dexcom for problems with the change on November 7, 2024; and (3) in a response letter dated December 3, 2024, Dexcom provided additional data in support of the change, presumably before agreeing to stop “commercial distribution” of G7 products with the change sometime before the FDA’s March 4, 2025, warning letter.

A former senior director of manufacturing at the facility the FDA inspected in June 2024 described how Dexcom made design choices that lacked scientific backing — for example, assuming that different needle shapes would work similarly.

“Dexcom definitely dropped the ball,” said Edward Carr, adding, “The arrogance of Dexcom is really what needed to be reset.”

And the problems with the G7 have persisted, even though, according to an interview given by incoming CEO Jake Leach on the Diabetech podcast in July, Dexcom stopped using the new membrane material.

Endocrinologists and pharmacists have taken notice, too.

The program director of a diabetes center in California told Hunterbrook he became increasingly frustrated with Dexcom “gaslighting” its customers — and providing “no public recognition and no recognition to doctors who are prescribing this.”

He summed it up: “All is not right in the world of G7.”

“Dexcom definitely dropped the ball.”

– Edward Carr, former senior director of manufacturing at Dexcom’s Critical Arizona facility

Dr. Jonathan Figueroa, an endocrinologist at NYU Langone, witnessed this dynamic firsthand.

Figueroa told Hunterbrook he had many patients report issues with the G7 this year. When he raised concerns with a Dexcom representative, he was told the company was unaware of any issues, he said.

Now, the consequences of Dexcom’s “arrogance” are starting to leak out — and patients are organizing. A Facebook group dedicated to G7 problems has exploded to 58,000 members in the past year.

Figueroa said there’s a Facebook group of endocrinologists and they have been documenting G7 complaints as well.

A Hunterbrook data analysis reveals the FDA receives more complaints about the accuracy of Dexcom devices than does its main competitor Abbott, even after controlling for market share.

In May, based on separate issues than those identified in the FDA’s March warning letter, G7 receivers were recalled for failing to sound an alarm when blood sugar becomes dangerously low or high. As of July, the FDA reported at least 56 injuries related to the recall. It was categorized by the FDA as Class 1, the most serious type of recall, for defects where “there is a reasonable chance that a product will cause serious health problems or death.”

Patients and doctors have reported a host of concerns about the G7, including data signal loss, inaccurate glucose readings, complete device failures, and adhesive issues. In July, Dexcom issued another Class 1 recall notice announcing a smartphone app update to correct a software flaw that may not alert users when their sensor fails.

Sensor inaccuracies in the G7 are particularly high on the first day of use — a problem possibly unique to that model — according to Dr. Michael Weintraub, an endocrinologist who specializes in diabetes.

Several G7 users told Hunterbrook their sensors rarely last the full 10.5-day wear time. Every premature sensor failure means requesting a replacement from Dexcom, which users described as a time-consuming and frustrating process. Dexcom is planning to launch a sensor that lasts 15 days.

Some users have sought to switch from the G7 to the earlier G6 or a competitor like Abbott, only to run into insurance coverage issues and compatibility hassles. Not all insulin pumps work with every CGM.

Publicly, Dexcom has brushed aside G7 reliability issues — “Things happen,” the new CEO said.

As recently as an investor conference on September 10, Dexcom’s vice president of finance and investor relations cast G7 complaints as “minor things” inside an otherwise “best-in-class” platform.

When directly asked if there was “anything that would be big enough to rise to the level of something we need to worry about from the next couple quarters,” he answered firmly, “No, no, by no means.”

But at some level, Dexcom appears to recognize that the G7’s problems are symptomatic of a deeper struggle. A once exceptional company has lost its way in its effort to compete — cutting corners to keep alive a growth story that seems increasingly out of reach.

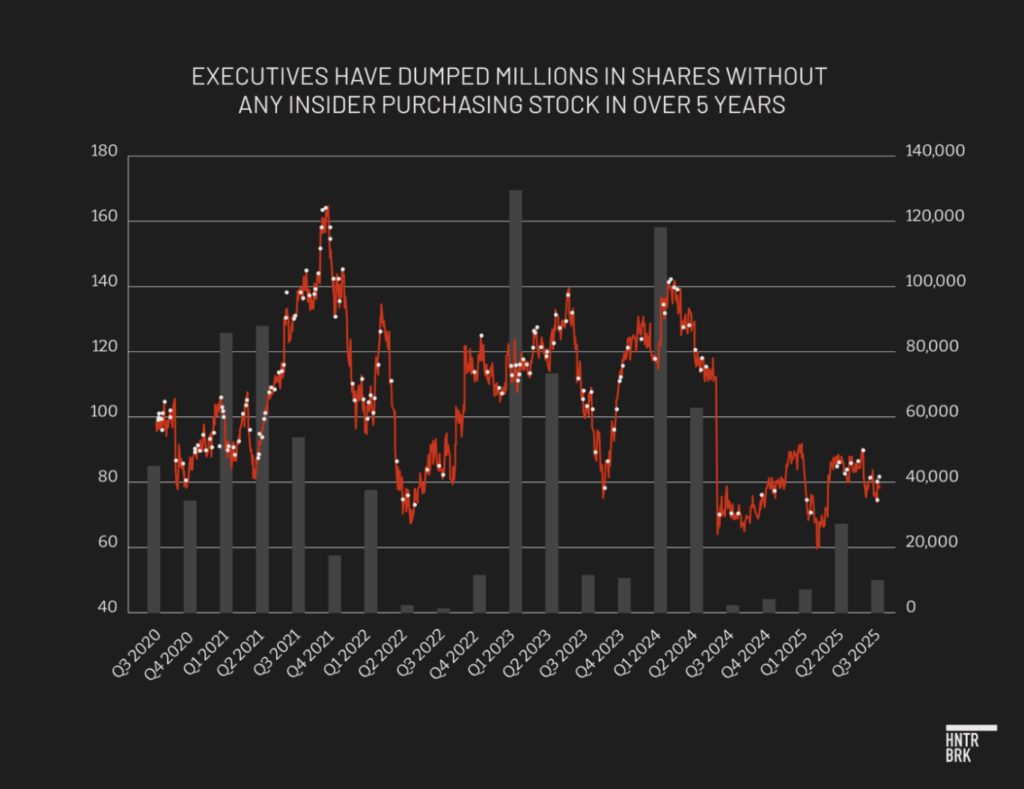

In the past year, the senior executives who have left Dexcom include the CEO, CCO, vice president of global operations, and head of engineering, according to a review of LinkedIn profiles and deleted webpages. No insider appears to have purchased Dexcom stock since early 2020.

Earlier this week, CEO Kevin Sayer stepped down suddenly on “temporary medical leave,” according to an 8-K filing, a few days after Hunterbrook’s first request for comment. The company previously reported Sayer would serve as CEO until the start of 2026, then transition to executive chairman, ensuring a smooth transition to Leach’s takeover.

Instead, he’s apparently out as active CEO months ahead of plan and no longer acting as chairman.

This comes as Dexcom faces a range of threats — from a proposed Medicare rule that could reduce profit margins; to the rise of GLP-1 drugs, which have the potential to slow the progression from prediabetes to diabetes and reduce insulin usage or disease severity; to the recent shuttering of the medical devices program at Alphabet’s Verily, the hardware supplier Dexcom relied on for the creation of the G7.

Meanwhile, Dexcom has turned to aggressive accounting to mask deteriorating fundamentals, according to Nick Gibbons, a Hunterbrook advisor and forensic accountant. Gibbons teaches forensic accounting at New York University and was previously head of quantitative forensic research at Citadel, one of the largest hedge funds, among other investment roles.

The consequence: The company’s financials appear to be a ticking time bomb. Last time Dexcom played similar games with its accounting in early 2024, which were highlighted by the accounting firm Behind The Numbers, it then released disappointing earnings, resulting in a 40% stock decline.

But for diabetics who rely on CGMs, there’s much more at stake than money.

CGMs revolutionized diabetes care. By replacing finger pricks and mental math with a stream of data, they improved millions of lives. Adoption exploded from 20% of Type 1 diabetics in the early 2010s to over 49% by 2019, one study found. Including Type 2 diabetics and some users without diabetes, more than 2.4 million Americans use millions of CGM sensors each month.

Dexcom helped lead that revolution.

But now the trust it has built over decades has begun to erode.

“Things happen.”

— Jake Leach, Dexcom’s incoming CEO, responding to G7 complaints

Dexcom sold the G7 as a “diabetic dream” to Billy Sosbe, his sisters recalled.

“It’s almost like a savior walked in the room,” said his sister, Janet Ladurini.

He was excited to replace the finger prick measurements that had kept him alive for 20 years.

Within eight months, he was dead.

“The Arrogance of Dexcom”

The FDA hadn’t visited Dexcom’s Mesa, Arizona, manufacturing facility in nearly five years when inspectors appeared at the door in 2024, according to Carr, the facility’s former senior director of manufacturing.

Within hours, a routine inspection turned into a corporate emergency. Corporate leaders flew in from headquarters.

A 25-year veteran FDA auditor and a scientist asked about Dexcom’s manufacturing process and data, recalled Carr.

What inspectors found may help explain why Dexcom users are being hospitalized.

In December 2023, Dexcom had quietly swapped a critical component in its G7 sensors.

The original design used a silicone compound produced by a third-party supplier, to coat the hair-thin filament that measures glucose under the skin. Dexcom and Abbott CGM sensors rely on a thin wire that rests just under patients’ skin called a “filament.” The filament picks up electrochemical signals of glucose presence, which the sensor interprets through an algorithm to generate glucose concentration readings. This membrane coating prevents interference from other chemicals like acetaminophen that can throw off readings. It ensures accurate glucose measurements that insulin pumps rely on for dosing decisions.

Dexcom replaced it with an in-house formulation. The FDA privately alerted Dexcom leadership that the company’s own tests showed the coating performed worse, according to FDA documents exclusively published by Hunterbrook.

Later, once the FDA’s warning letter was published, incoming CEO Leach, who had spent years at the company in engineering roles including chief technology officer, told a different story on a podcast.

“What is important to note is that there’s no actual claim that the performance of the sensor isn’t as accurate as the old one,” Leach said on Diabetech this summer.

But the FDA inspection documents appear to contradict him.

Sensors with the new material showed “significantly different” glucose sensitivity over time. They performed worse on “every accuracy metric.”

Patients using the altered sensors “may experience differences in accuracy over the 10.5-day sensor wear period,” inspectors wrote, based on Dexcom’s own data.

This change to a “critical raw ingredient” required regulatory clearance before implementation, according to the FDA. For devices regulated under the 510(k) pathway that Dexcom used to obtain clearance for the G7, companies must submit premarket notification to the FDA at least 90 days before introducing a product into interstate commerce after it has been “significantly changed or modified in design, components, method of manufacture, or intended use.” Dexcom never sought that FDA sign-off, apparently because they believed the change was “non-significant.”

Their regulator, however, disagreed.

The FDA also deemed the company’s risk analysis of the G7 “inadequate and incomplete,” specifically citing dangers with automated insulin dosing. Exact language from the warning letter: “The larger inaccuracies in (b)(4)-coated sensors cause higher risks for users who rely on the sensors to dose insulin or make other diabetes treatment decisions.” Note: “(b)(4)” in the FDA warning letter indicates text redacted in accordance with FOIA exemption 4, permitting agencies to withhold trade secrets and other confidential commercial information.

“I think the way Dexcom had done its design process, which translated to manufacturing process, were probably not the best in the world,” said Carr, the former Mesa facility director.

He added: “When the FDA asked for a lot of the data and reasoning behind how Dexcom had set up its manufacturing processes, because Dexcom had grown so fast so quick, they could not really produce really good data and analysis to show why they had come up with the manufacturing processes.”

The FDA did not respond to questions on the G7 or warning letter. The agency did, however, recently clear a version of the G7 that can be worn for an extended 15 days — though, notably, the 15-day version of the G7 is only cleared for adults. Those 17 and under can continue using the 10.5-day G7.

Though not diabetic himself, Carr — who said he was let go by Dexcom in January — wears the G7 and believes it is both safe and accurate. He maintains that Dexcom generally tries to do the right thing. But he took issue with Dexcom’s manufacturing and design processes, for years unchecked by the FDA.

Several former employees proposed an emphasis on improving revenue and margins as explanations for the G7’s flaws. Carr had a more nuanced take, noting that the company made design choices with correct intent but lacking diligence, failing to adequately research and validate its decisions.

He described some unscientific assumptions made at Dexcom. That different needle shapes would work the same. That alternate sensor coatings were interchangeable. That changes could be made without rigorous validation.

“Best guesses that were made along the way,” Carr said. The FDA’s warning letter, issued in March 2025, used a different term: Dexcom had “adulterated” its devices.

Between December 2023 and the warning letter, Dexcom likely continued manufacturing the altered devices.

Hunterbrook’s analysis shows that devices manufactured after the sensor change drew significantly more accuracy-related complaints from users. Users reported readings off by hundreds of points. Sensors failing after days instead of lasting the promised 10.

Dangerous false lows and, worse, false highs that could trigger insulin overdoses.

“As a Type 1, I understand we’re not like the Dexcom engineer expert,” diabetes advocate and author Quinn Nystrom told Hunterbrook. “Because we rely on it every second of every day, we know if it’s working or not working.”

“Because we rely on it every second of every day, we know if it’s working or not working.”

— Quinn Nystrom, a diabetes advocate and author

It’s unclear precisely when Dexcom stopped manufacturing sensors with the unauthorized membrane coating, but supply chain lags mean patients could still be using these compromised sensors today. According to Hunterbrook’s analysis of FDA records, it takes, on average, about 230 days from the date of manufacture for complaints about accuracy problems to be filed.

The Numbers Don’t Match the Message

Two lime green characters glowed atop Dexcom’s booth at an August diabetes conference in Phoenix, Arizona: “G7. “

Beneath it, the claim: “the most accurate CGM. period.”

In a dim bathroom next to the booth, the reality of life with a G7 came into stark relief.

David Jopke discarded a failed G7 — and popped a fresh unit on the back of his right arm.

“Is some of the messaging dangerous?” Jopke asked. “Well, potentially.”

He added: “These are, at heart, companies that are trying to sell a product.”

The world met the G7 with a confident kickoff in a 2023 Super Bowl ad. Nick Jonas flipped it into the air like a coin.

That Nick Jonas ad — boasting “No Fingersticks” — has since vanished from the company’s YouTube channel. Jonas could not be reached for comment.

But Dexcom is still marketing the G7 as the most accurate CGM, despite mounting evidence to the contrary.

Hunterbrook analyzed every adverse event report submitted to the FDA’s Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database, known as MAUDE — a public repository for medical device complaints — between the date of the first complaint for each product and the end of 2024, using natural language processing to isolate complaints specifically about inaccurate glucose readings. A reporter then compared complaint rates across manufacturers, adjusting for estimated market share.

If all CGM devices had comparable reliability and users reported problems at similar rates, then the percentage of complaints to the FDA about Dexcom would mirror its CGM market share in the U.S.

Instead, Dexcom’s share of accuracy complaints is 22% more than its market share. Meanwhile Abbott — maker of the competing Freestyle Libre 3 — logs 68% fewer. Methods Scope. We scraped every CGM adverse event submitted to the FDA’s MAUDE database through 12/31/2024. Filter for inaccuracy. NLP flagged narratives containing terms such as “inaccurate,” “false high/low,” “off by,” or “meter mismatch.” Normalization. To compare companies, we benchmarked each firm’s share of accuracy‑related complaints against its U.S. CGM market share, which we (roughly) estimated using a range of publicly available sources; at device level (G7 vs. G6), we used the share of each device’s MAUDE total to isolate accuracy mix. Key metrics. According to studies sponsored by their manufacturers, Dexcom’s clinical MARD for G7 is 8.2% while Abbott’s Libre 3 is 7.9% (lower is better); our analysis tests whether real‑world complaint patterns track those headline claims. Limitations. MAUDE is a passive system with reporting bias; complaint rates are not incidence rates. We use it to spot signal and timing, not to compute clinical accuracy. These deviations suggest that factors beyond market share, like device performance, likely contribute to the imbalance.

The G7 stands out as the worst performer.

Even nondiabetics have taken notice.

“It’s nearly always inaccurate for me,” Bryan Johnson, the Silicon Valley entrepreneur known for intensive health monitoring and biohacking, texted about the G7.

Dexcom touts its 8.2% “mean absolute relative difference,” or MARD, the percentage by which CGM readings differ from actual blood glucose, on average. Lower MARD means better accuracy. CGMs with MARD scores under 10% are considered accurate enough to adjust medications without backup confirmation by finger prick. , Dexcom’s “most accurate” claim comes courtesy of a clinical trial conducted for FDA clearance of the G7. In clearing the G7, the FDA determined it was at least as accurate as a G6. The results of that clinical trial were published as two studies, separated for adult and pediatric users. Abbott’s Freestyle Libre 3 generated the first MARD score under 8%, with an overall MARD of 7.9%.

But real-world FDA data tell a different story: Accuracy complaints comprise about 13% of all G7 reports, more than double the nearly 6% rate for the older G6 model, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis.

The timing of the complaint surge seems to be revealing.

G7 accuracy reports spiked dramatically for devices manufactured after December 2023, just when, as the FDA revealed, Dexcom implemented its unauthorized material change.

In the second half of 2024, complaints about the G7’s accuracy climbed again — this time coinciding with a sharp rise in imports from Dexcom’s new Malaysian facility, according to trade data.

Kamil Armacky, who runs the YouTube channel Nerdabetic, routinely asks users with G7 complaints to check their box’s manufacturing location. “It’s more likely than not that it was probably in Malaysia,” he said in a June episode of the Diabetech podcast, implying a correlation between sensor failures and Dexcom’s international manufacturing site.

Hunterbrook could find no evidence that Dexcom’s manufacturing process in Malaysia differed from that at its U.S. facilities.

Abbott, meanwhile, decided to challenge Dexcom’s claims head-on.

In 2024, Abbott published a direct comparison study showing the Freestyle Libre 3 beat the G7’s accuracy “throughout all days of sensor wear in all glycemic ranges,” according to the authors.

While the Abbott-funded study should be viewed with natural skepticism, Hunterbrook’s analysis shows Abbott’s device has generated fewer real-world complaints, even after controlling for market share.

When the FDA’s March warning letter noted Dexcom had changed MARD specifications for both the G7 and G6 — changes that “could result in all commercial sensors being released with borderline acceptable MARD” — Dexcom pushed back. Company spokesperson Nadia Conard told reporters the company was “surprised” by the FDA’s findings, claiming all changes were backed by “extensive testing.”

In a March SEC filing about the warning letter, the company vaguely told investors it would “undertake certain corrections.”

Six months later, on September 8, analysts at the investment bank Oppenheimer downgraded Dexcom due to “various challenges,” noting “field checks point to rising concerns about G7 accuracy/performance.”

Oppenheimer also cited competition from Abbott, competitive bidding on the horizon, and issues in the over-the-counter market, among other financial concerns. Regarding product quality, it concluded: “There seems to be a manufacturing/software quality control issue somewhere.”

Oppenheimer did not cite cases of hospitalizations or deaths following G7 quality issues, which Hunterbrook appears to be reporting here for the first time.

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2014/FDA-Approves-Dexcom-Software-with-Artificial-Pancreas-Algorithm

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2015/FDA-Approves-Dexcom-G5-Mobile-Continuous-Glucose-Monitoring-System/

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2016/FDA-Approval-of-Dexcoms-Non-Adjunctive-Indication-Triggers-a-New-Era-in-Diabetes-Management/

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2018/FDA-Authorizes-Marketing-of-the-New-Dexcom-G6-CGM-Eliminating-Need-for-Fingerstick-Blood-Testing-for-People-with-Diabetes/

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2018/Dexcom-G6-Continuous-Glucose-Monitoring-System-Will-Be-Available-to-Medicare-Beneficiaries-with-Diabetes-in-Early-2019/

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2022/Dexcom-G7-Receives-CE-Mark–Next-Generation-Continuous-Glucose-Monitoring-System-to-Revolutionize-Diabetes-Management/

https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20221208005302/en/Dexcom-G7-Receives-FDA-Clearance-The-Most-Accurate-Continuous-Glucose-Monitoring-System-Cleared-in-the-U.S.

https://investors.dexcom.com/news/news-details/2023/Dexcom-G7-Continuous-Glucose-Monitoring-System-Will-Be-Available-to-Medicare-Beneficiaries-at-Launch/

The Accounting Game

Dexcom appears to have turned to aggressive accounting to mask deteriorating fundamentals, according to Hunterbrook advisor and forensic accountant Nick Gibbons.

Dexcom’s latest financial reporting raises questions about the sustainability of its growth. The company’s revenue recognition practices appear to have boosted current performance by pulling forward future sales.

Days sales outstanding — the average time it takes sales to convert into cash — surged to a record 106 days in the quarter, up six days from Q1 and 20 days from a year earlier. This sharp rise in receivables suggests revenue is outpacing cash collection or that excess product is being pushed into distribution channels beyond actual end-customer demand, raising concerns about the quality of reported revenue.

The quarter after Dexcom’s DSO spiked near 100 in early 2024 — an issue flagged at the time by the accounting group A Peek Behind The Numbers — the company’s stock fell around 40%.

In its second-quarter 2025 SEC filing, Dexcom attributed the increase to “timing of sales and customer collections.” But according to forensic accounting, Dexcom’s specific pattern of rising DSO suggests the company is booking revenue prematurely or channel stuffing, heightening the risk of weaker future performance as Dexcom may need to fill the gap left by demand that was pulled forward.

Dexcom’s profitability is also under strain.

Gross margin has now fallen year over year for 15 consecutive quarters, slipping to 59.5% in the second quarter. While the company has offered a range of explanations, the problems appear structural rather than temporary. Analyst notes at banks ranging from Goldman Sachs to JPMorgan have recently targeted gross margins well above 60% as consensus benchmark, alongside >15% annual growth.

The sustained margin pressure stems in part from mounting excess and obsolete inventory charges, likely tied to product issues, according to Hunterbrook’s forensic accounting expert.

Dexcom recorded $9.4 million in such charges in the first half of 2024; a record $44.1 million in the second half of 2024, tied to faulty build configurations and sensors damaged during shipment; and another $37.0 million in the first half of 2025, linked to damaged sensors and a receiver recall.

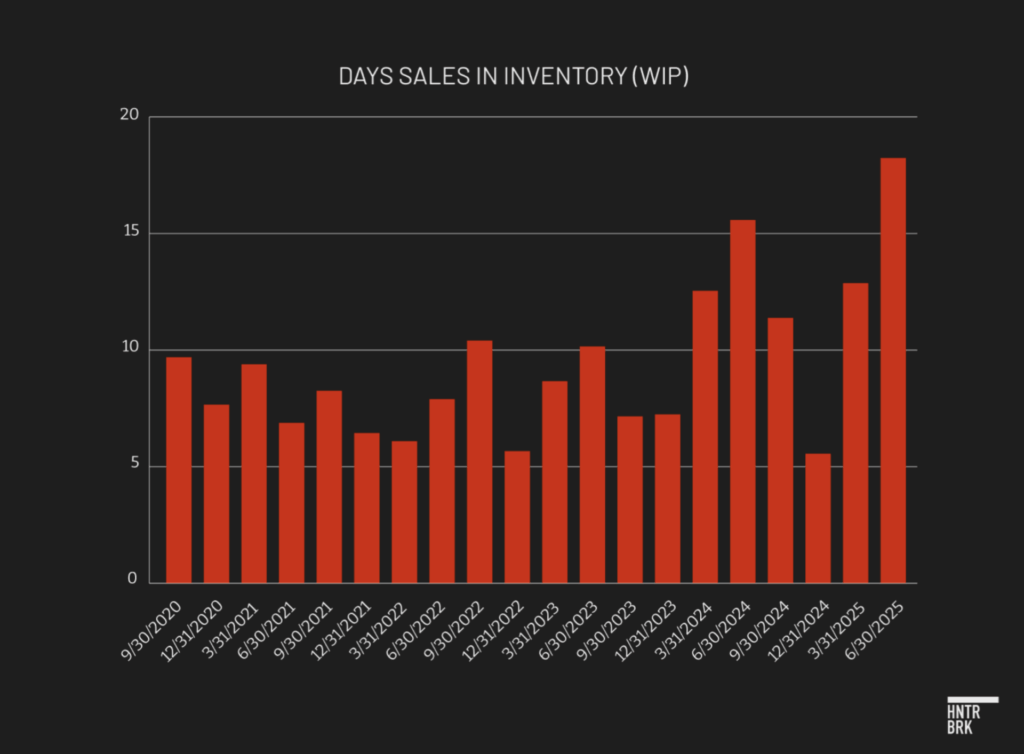

An unusual shift in Dexcom’s inventory composition adds another layer of concern, according to Gibbons.

Work-in-process (WIP) days of inventory spiked to 18 days — more than double the 2023 quarterly average of 8 and well above the average of 11 in 2024.

Unlike finished goods, which can be valued against observable selling prices and historical margins, WIP requires management to allocate labor, overhead, and material costs to partially completed units. That judgment introduces more estimation error and subjectivity. It complicates the calculation of excess and obsolete charges, creating greater opportunity for misstatement.

Gibbons noted that the buildup may indicate Dexcom’s CGMs are becoming more expensive to make, either through higher actual production costs or through accounting maneuvers that shift more overhead costs onto inventory.

Either way, when these higher production cost units are eventually sold, they will drag down profit margins further. The trend also raises questions about whether inventory accounting is being used to obscure deeper profitability challenges.

The Stelo: Over-The-Counter, Over-Promise

With declining margins and a saturated CGM market in Type 1 Diabetes, Dexcom jumped into the consumer wellness space with a new product called Stelo.

The device is an over-the-counter CGM for those who do not use insulin. That includes nondiabetics. It tracks how diet and exercise affect blood sugar. The March 2024 FDA clearance made it the first prescription-free CGM. It was cleared based on its “substantial similarity” to the G7. Stelo has been marketed by Dexcom with similar fervor.

Dexcom painted Stelo as a potential game-changer that could reach millions of health-conscious consumers. A lifestyle more than a lifeline. A health product analogous to a Fitbit or Apple Watch.

But it doesn’t seem to be going great.

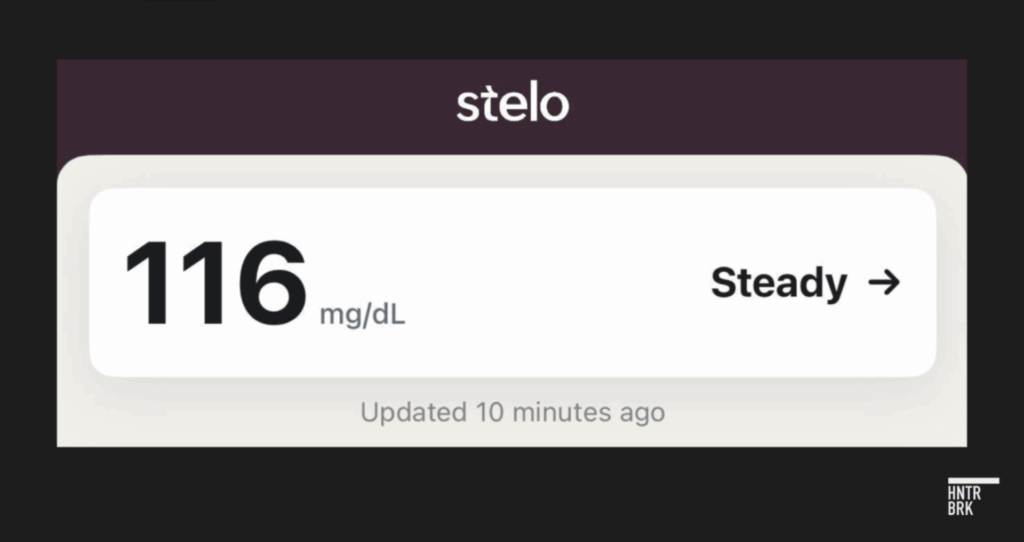

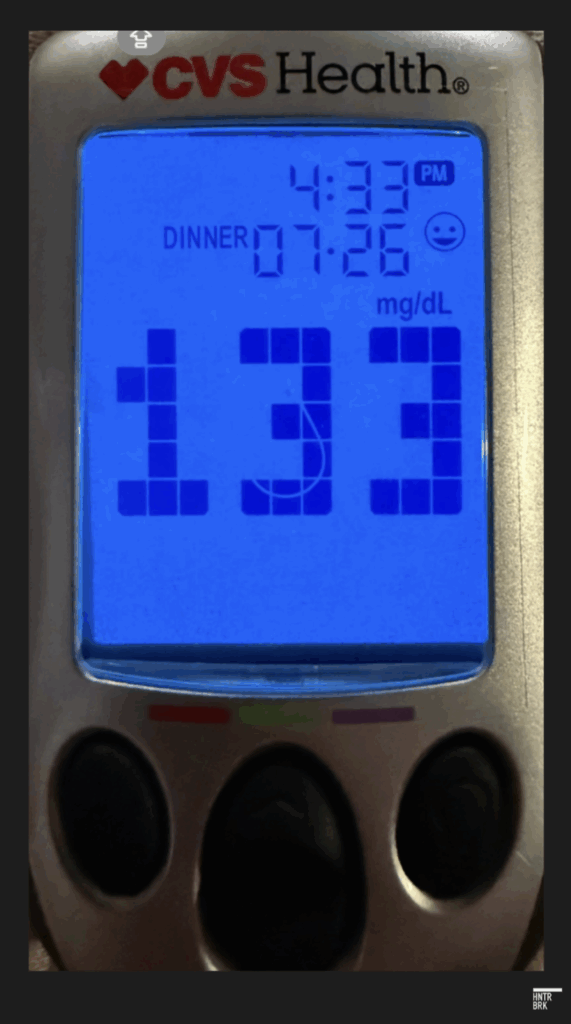

When tested by a Hunterbrook reporter, the device showed significant accuracy problems.

After a meal on day two, Dexcom’s Stelo measured a steady reading of 116 mg/dL.

A simultaneous finger stick reading showed 133 mg/dL — a 17-point difference, which is particularly meaningful given the reporter does not have diabetes, therefore likely has a tighter blood sugar range.

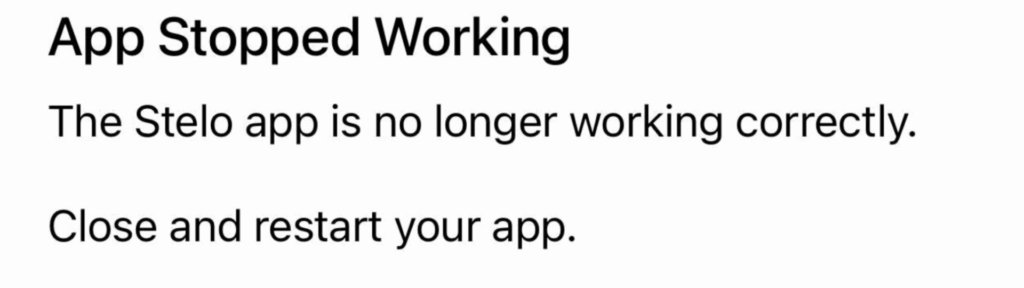

The Stelo app also crashed multiple times during the four-day test period.

It wasn’t just one reporter.

Stelo has also generated hundreds of adverse reports to the FDA and today carries a mediocre 2.9 star rating on Amazon. The average star rating on Amazon was 4.23, according to a 2023 report.

“They aren’t reliable and you may not be able to tell when they are spewing worthless/misleading readings,” one review of the Stelo said in May.

Stelo complaints grew so frequent they prompted a federal lawsuit in June. An unrelated software company that does business under the name “Stelo” claimed its brand was tainted because Dexcom named its product similarly and its customer service couldn’t handle patient complaints.

According to the lawsuit, thousands of confused users contacted the wrong Stelo company with complaints about Dexcom’s device.

An example: “I purchased [your] … glucose sensor in October of 2024….[My wife] started using it and after using it for about 8 days or so the sensor came apart. It came out of the arm that my wife was using it for. I think it broke off and, I think where there is a needle or whatever is still embedded in the, inside her. I was wondering what we need to do and what the procedure is.”

Living with Dexcom’s Flaws – Or Leaving

For many of the millions depending on Dexcom’s CGMs, corporate dysfunction can mean terror.

Kelli Danielson woke to paramedics crowding her living room. Six hours earlier, she’d lain down for a nap with her G7 showing normal blood sugar. While she slept, the device failed completely.

Her husband found her unresponsive on the couch.

When EMTs arrived, her blood sugar had fallen beneath the lowest limit their equipment could detect.

“That’s when I realized I REALLY couldn’t trust Dexcom’s readings,” Danielson wrote Hunterbrook. “What if I lived alone? I really could have died!”

“That’s when I realized I REALLY couldn’t trust Dexcom’s readings,” Danielson told Hunterbrook. “What if I lived alone? I really could have died!”

— Kelli Danielson

Her other two sensors that month also failed. The replacements took three weeks to arrive.

Without insurance, CGMs typically cost between $1,200 and $7,000 annually. Even with coverage, patients are often stuck with few options. Insurance companies have preferred devices. Not all CGMs work with all insulin pumps.

Danielson didn’t have coverage for early refills and was unwilling to pay out of pocket for sensors likely to fail. So she spent a week doing finger sticks. Exactly what Dexcom promised to eliminate.

Beyond depending on Dexcom personally, Danielson is a pharmacist. She’s wrestled with giving her patients a product that she couldn’t trust. Danielson has also seen many of her customers switch from the G7 back to the G6, or from G7 to an Abbott CGM. “Even my sister in law … she was on the G6 and her doctor, of course, was like, ‘Oh, you need to switch to the G7.’ So she did, and after two sensors, she’s already back to the G6 again,” Danielson said.

“I almost feel unethical dispensing them, just because I know there’s been so many problems, and I’ve had so many problems,” she said.

Ashley Raymond, a 27-year-old runner in Austin, faced life-threatening problems during a yoga class in January.

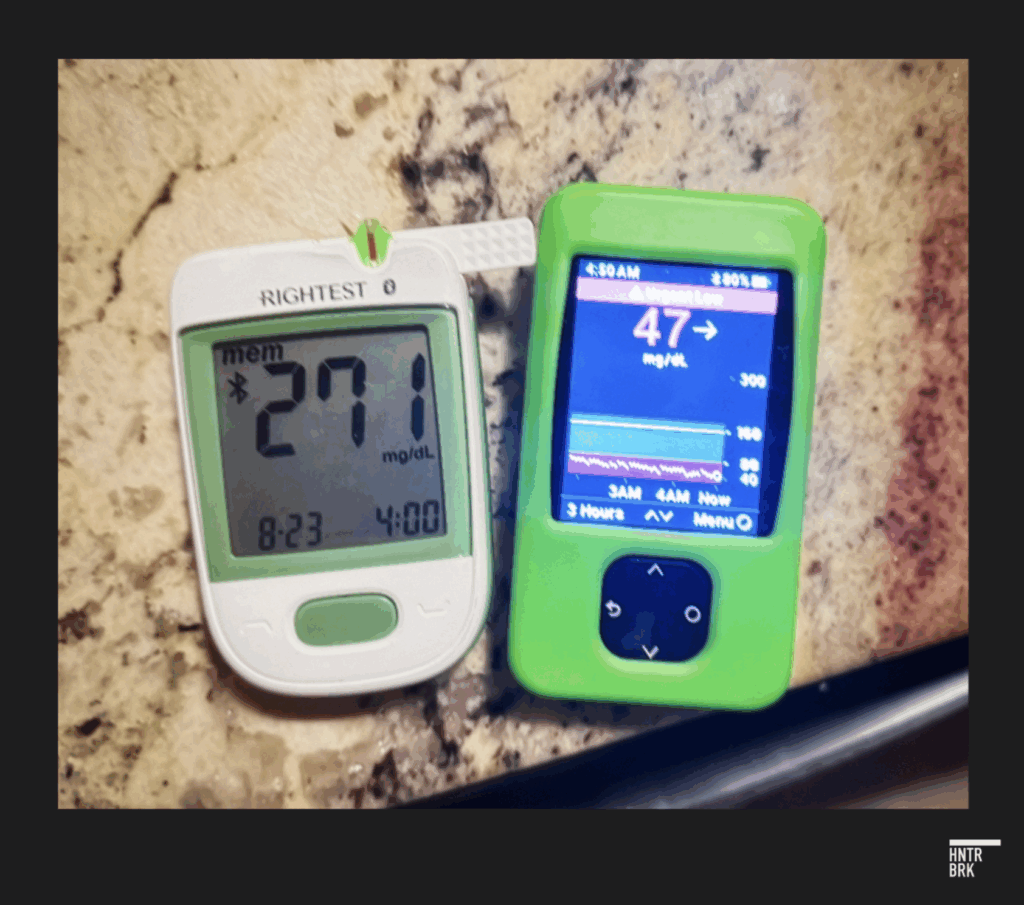

Twenty minutes in, she felt faint. Her G7 showed 170 — high, not low. She left class, pricked her finger, and discovered the truth: Her blood sugar was under 40. Her insulin pump, trusting the false high reading, had been dosing her with insulin she didn’t need.

“It’s absolutely terrifying,” Raymond said.

Even when the devices work, some users still live with constant doubt.

Lib Gatti, 36, of Boston, knows their G7 often shows false lows when they sleep on their side — pressure on the device can cause inaccurate readings. They’ve learned to ignore nighttime alarms, roll over, and hope for the best.

But even flawed technology beats the mental stress of wondering: “If I go low, will I wake up?”

Three of the five people in Gatti’s so-called “diabesties” group chat refused to upgrade from the G6, too worried about G7 errors.

Jessica Casey helps run the Facebook group dedicated to letting G7 users share their complaints.

A lifelong diabetic, she’s used Dexcom devices for 15 years. The G5 “never failed and was completely accurate.” Now, with macular atrophy affecting her vision, she can’t afford sensors that fail.

“The difference between not hospitalized, hospitalized, and dead,” Casey wrote Hunterbrook, “are a couple drops of insulin.”

Authors

Andrew Ford is an investigative journalist who exposed systemic flaws and prompted reforms in healthcare, business, policing and state government. His reporting was published by ProPublica, USA Today, The Arizona Republic, Asbury Park Press, and Florida Today. He holds a journalism bachelor’s from the University of Florida and is in his final semester of a data analytics master’s from Georgia Institute of Technology. He’s based in Phoenix, AZ.

Laura Wadsten is an investigative journalist specializing in healthcare. She began her career reporting on antitrust and health care markets as a Correspondent for The Capitol Forum, a premium subscription financial publication. Previously, she was Executive Director of the nonprofit Moving to Value Alliance, where she produced the MTVA Unscripted Podcast. Laura was a Hodson Scholar and Editor-in-Chief of The News-Letter at Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a B.A. in Medicine, Science & the Humanities.

Blake Spendley joined Hunterbrook from the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), where he led investigations as a Research Specialist for the Marine Corps and US Navy. He built and owns the leading open-source intelligence (OSINT) account on X/Twitter, called @OSINTTechnical (over 1 million followers), which also distributes Hunterbrook Media reporting. His OSINT research has been published in Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, and The Economist, among other top business outlets. He has a BA in Political Science from USC.

Michelle Cera trained as a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She completed her PhD in Sociology at New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. She has also served as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and innovative research methodologies.

Dhruv Patel is an investigative journalist based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, specializing in data-driven reporting. He helps spearhead investigative coverage at The Harvard Crimson, and his reporting has been cited and discussed by The New York Times, CNN, The Boston Globe, ABC News, and BBC, where he also frequently contributes commentary. A John Harvard Scholar at Harvard College, he studies computer science and economics to leverage machine learning for accountability journalism.

Editors

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar (taking much easier classes than Dhruv!) and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

This investigation underwent dedicated fact-checking, as well as review by Hunterbrook advisors Paul Steiger, the founder of ProPublica, and Bethany McLean, the best-selling author known for her investigative journalism into Enron. Design contributed by Alexander Spacher.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.