Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $PDD at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

The latest blow in the brewing U.S.-China trade war: The U.S. Postal Service temporarily suspended parcels from China and Hong Kong before announcing it would be resuming shipping on Wednesday.

The USPS action hit shipping by Chinese retailers like Temu, owned by PDD Holdings (NASDAQ: $PDD); its closest competitor Shein, which had planned to IPO in the U.S., then due to scrutiny shifted toward London, where it has since been judicially challenged by the nonprofit Stop Uyghur Genocide; and JD.com (NASDAQ: $JD), an e-commerce platform based in China.

In a brief note posted Tuesday evening, the USPS announced “International service disruptions” with the temporary suspension of packages from China and Hong Kong.

On Wednesday morning, the USPS updated the page to say it would be “accepting all international inbound mail and packages from China and Hong Kong Posts” — but would be “working closely together” with Customs and Border Protection “to implement an efficient collection mechanism for the new China tariffs to ensure the least disruption to package delivery.”

The USPS suspension follows a 10% tariff on imports that had previously been protected by what is known as the “de minimis exemption,” which had exempted packages worth less than $800.

“Prices on such orders could now go up an average of 30 percent,” reported The Washington Post.

China retaliated with a range of tariffs on U.S. exports.

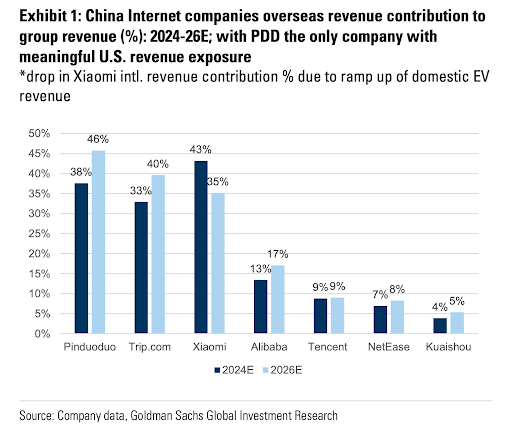

“PDD’s Temu has the highest US exposure amongst China cross-border players,” wrote

Goldman Sachs analysts in a Tuesday evening research note hours before the USPS news. “Temu will also bear a portion of the extra tariff/tax cost burden (36% extra cost for full-entrusted products, which we estimate contributes approximately 70% of Temu US’s GMV),” referring to gross merchandise value.

“The Trump administration is focused on targeting de minimis for another reason: its apparent ties to the fentanyl trade,” reported The New York Times.

A bipartisan Congressional letter in September, 2024, urged then-President Biden “to use executive authority to end the dangerous de minimis loophole and protect Americans from its growing dangers,” claiming that “increasingly, the loophole is being exploited by drug cartels and criminals to facilitate the importation of deadly substances like fentanyl.”

According to a Congressional investigation “Fast Fashion and the Uyghur Genocide” released in 2023, “Temu and Shein alone are likely responsible for more than 30% of all packages shipped to the United States daily under the de minimis provision.”

Temu appears to represent the majority of PDD’s annual revenue — with an estimated 40% of its sales coming from the United States in 2023.

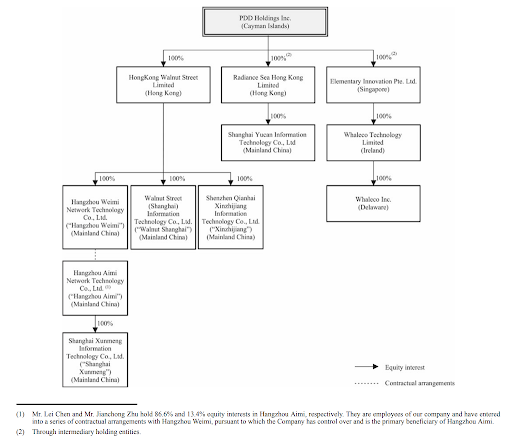

Source: PDD Form 20-F SEC Filing

Forced Labor Sanctions?

Semafor reported on Tuesday evening that the Trump administration is also considering adding Temu and Shein to the Department of Homeland Security’s forced labor entity list.

In the 2023 investigation, Congress found that “Temu does not have any system to ensure compliance with the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA),” and that “Both Temu and Shein rely heavily on the de minimis exception to ship packages directly to U.S. consumers, allowing them to provide less robust data to CBP [Customs and Border Protection], avoid import duties, and minimize the likelihood that the packages will be screened for UFLPA compliance.”

The Congressional investigation also found “Temu conducts no audits and reports no compliance system” and that “Temu’s business model, which relies on the de minimis provision, is to avoid bearing responsibility for compliance with the UFLPA and other prohibitions on forced labor while relying on tens of thousands of Chinese suppliers to ship goods direct to U.S. consumers.” Temu conceded that it “does not expressly prohibit third-party sellers from selling products based on their origin in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region.”

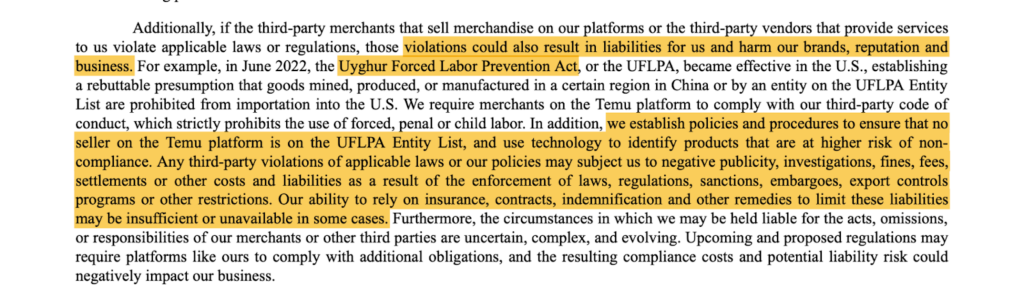

In its latest Form 20-F SEC filing, PDD noted the risk of UFLPA violations to its business.

PDD claimed that “we establish policies and procedures to ensure that no seller on the Temu platform is on the UFLPA Entity List,” the same list to which the Trump administration is now reportedly considering adding PDD.

Hunterbrook previously exposed the American agricultural giant Archer-Daniels-Midland (NYSE: $ADM) for false statements about its presence in Xinjiang, the Chinese region known for forced labor. Experts told Hunterbrook that the UFLPA could be one tool the government could use against a subsidiary in Xinjiang owned, in part, by ADM.

PDD is also the focus of a federal class action lawsuit that alleges “PDD has no meaningful system to prevent goods made by forced labor from being sold on its platform, and has openly sold banned products on its Temu platform.”

The litigation alleges that PDD’s applications contained malware designed to obtain user data without consent, including reading private text messages. A 2023 comparative analysis of cybersecurity at Temu versus peers claimed PDD had the most malware liabilities. PDD’s Pinduoduo app was temporarily removed from the Google store due to surveillance issues.

PDD did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment.

A Hunterbrook investigation also reveals three other Nasdaq-listed companies linked to Chinese tech surveillance: Datasea ($DTSS), Taoping ($TAOP), and Luokung ($LKCO), each of which have collapsed into microcap territory.

Asked to comment on whether it would explore delisting these companies, the Nasdaq declined.

Several Companies Enabling Chinese Surveillance Remain Listed on Nasdaq

Abduweli Ayup planned to open a chain of kindergartens teaching the Uyghur language. But in the Xinjiang province of China, where officials equate Uyghur traditions with criminal behavior, Ayup’s schools swiftly attracted police attention.

In 2013, Ayup — a linguist, poet, and scholar — was taken into custody, questioned, and eventually sentenced to 18 months in prison for illegal fundraising. As police presented the case against him, Ayup realized that his cellphone had been monitored, his email checked, and his location tracked. Once the government released Ayup, after more than a year in prison, he remained haunted.

“I feel like I’m naked all the time,” Ayup told Hunterbrook. “I felt that I was not even safe at home.”

Across China, increasingly sophisticated technology has ushered in a new era of surveillance, designed to harass, intimidate, and control people opaquely branded as threats to public security.

This surveillance is at its most severe and intense in Xinjiang, the vast Central Asian territory where many Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities have been persecuted. In Xinjiang, officials force citizens to download surveillance apps on their phones and identify themselves at checkpoints. In some cases, officials arrest citizens and sentence them to years in internment camps.

Officials also use versions of the tools wielded against Uyghurs and Muslim minorities throughout China to suppress other people the government considers a threat. That typically includes people with a history of filing petitions or complaints against the government.

“The goal of its systems is to prevent even the possibility of dissent,” said Maya Wang, associate China director at Human Rights Watch.

Behind the sweeping tendrils of surveillance are companies that profit from selling invasive technology to public security bureaus. A Hunterbrook investigation reveals that three technology companies — Taoping, Datasea, and Luokung — are currently trading on the Nasdaq, despite a decline into the microcap territory associated with delisting.

Taoping, Datasea, and Luokung did not respond to Hunterbrook’s requests for comment.

Like other small companies, they already face significant vulnerabilities on the Nasdaq. They risk being delisted if their share price falls below $1 for 30 days, their market capitalization dips too low, or they fail to file timely financial reports. They also fall into a category of growing scrutiny by U.S. lawmakers: companies that supply Chinese police with surveillance tools that can be used to repress minority groups, peaceful dissidents, and other citizens.

Reviewing publicly available contracts, government tenders, company announcements, and relevant articles on Chinese-language sites, Hunterbrook has determined that the technology developed by these three companies is used by police to stifle political dissent, infringe on human rights, and increase surveillance.

Taoping: The Company Aiding China in Solving “The Difficult Problem of How To Control People”

Taoping, a China-based tech company known for its cloud-based and artificial intelligence products, advertises its “smart screens” on a central page of its company website. Toward the bottom of the page, a series of massive monitors display highways, city streets, and residential neighborhoods.

These images are of screens used in “command centers,” facilities Taoping has supplied to cities like Beijing, and Shenzhen through its subsidiary iASPEC. Taoping has a long history of developing tools for police surveillance. The company was briefly named “China Public Security Technology Inc.” Some of Taoping’s early clients were Chinese entities known as public security bureaus.

Foshan is another city that Taoping has helped supply with command centers, according to trade data reviewed by Huntebrook. Foshan has vastly expanded its surveillance technology in recent years: it has installed cameras not only in city streets, but at bus stations dotted along mountain hikes. In Xiqiao, a Foshan district, government records show that officials purchased at least 1,400 cameras and 300 facial recognition cameras between 2006 and 2019. In a government document obtained by China File and viewed by Hunterbrook, officials stated their hope that this equipment would enable a “breakthrough in addressing the difficult problem of how to control people.”

When Taoping supplies a city like Foshan with command centers, it equips police with the technology needed to sift through vast amounts of data gathered from these cameras. That means large smart screens, like the ones shown on Taoping’s company website, to stream live video footage. It also means Internet of Things services and machine learning programs to analyze and assess information. For example, in 2022, former Taoping subsidiary Wuda Ji’ao applied for a patent that was ultimately denied for its “social risk index classification model.” This system uses machine learning to assess “social stability,” trying to understand the correlation between “crime” and several obscure metrics, including “rate of petitions,” “social public morality,” and “social core value identity.”

Machine learning programs like Taoping’s, which attempt to analyze and predict where crimes, protests, and other social unrest will occur, typically encourage police to target communities considered to pose a risk to the Chinese government. That includes Uyghurs, other ethnic minorities, migrant workers, those with mental and psychosocial disabilities, and petitioners — even for carrying out mundane activities like donating to mosques or sending a message through WhatsApp.

“Predictive policing in China will mainly be a more refined tool for the selective suppression of already targeted groups by the police,” wrote Daniel Sprick, a scholar of Chinese law at the University Cologne, in a 2019 paper. For this reason, Sprick concludes, it “does not substantially reduce crime or increase overall security.”

Datasea: Audio Surveillance

For decades, China has blanketed its cities with cameras, expanding its vast network of visual surveillance. More recently, the government has also been collecting personal information through another form of monitoring: audio surveillance.

In 2021, a white paper published by Datasea subsidiary Shuhai Zhangxun commented on the state of public security; now that “video monitors have been basically deployed,” it reads, “audio monitors will be the next focus.” The paper goes on to suggest this technology be applied to “criminal investigation and criminal tracking in public security and justice.”

Datasea is known for its security systems and 5G messaging services. The company has been developing acoustic intelligence for a variety of partners. In October 2022, Datasea signed an agreement with China City Vision Investment Group to work on “acoustic intelligence, and urban and rural operations.” Another Datasea subsidiary, Xunrui Technology, developed audio surveillance products for “anti-terrorism and stability maintenance.” According to an article posted by Datasea’s corporate account, audio surveillance, a key “security” tool, is now used in airports, railways, banks, and elsewhere.

While Hunterbrook has not confirmed where Datasea deploys acoustic intelligence, there’s evidence to suggest its products may be used in Xinjiang.

In 2021, China City Vision Investment Group signed an agreement to work with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, a state-run paramilitary organization currently sanctioned by the U.S. government for its leading role in repression and the use of forced labor in Xinjiang. Datasea’s website also frequently mentions the use of audio monitoring in “anti-terrorism work,” a term most often used in connection to Uyghur and Muslim surveillance.

Although details around Datasea’s audio collection remain opaque, there’s documentation obtained by Human Rights Watch of China’s effort to collect a national database of “voice patterns,” samples that could alert police of people they deem suspicious speaking in private phone conversations.

This expanding field adds to China’s collection of other biometric data, from DNA samples to palm prints. Taken together, this personal data allows police to paint a comprehensive profile of citizens in police files. In the case of audio surveillance, this information is often collected without individuals’ awareness or consent.

“The mass collection data itself is a violation of human rights,” said Wang. “Human rights standards require that the collection of data be necessary, proportionate, and lawful.”

Luokung: Geographically Targeting Dissidents With “God’s Perspective”

In a 2017 interview, Zhang Dongpu, general manager of Luokung subsidiary Super Engine, showed a reporter for Taibo.com the company’s advanced mapping system, a dense display of colorful location points.

“There are 1 billion location data here,” Dongpu explained. By selecting two specific points, Dongpu pulled up two individual vehicles, displaying their trajectories on the map, as he put it “giving governments or business owners a ‘god’s perspective.’”

Geographic information systems, like the ones created by Luokung, are used by government policing systems across the world. These systems, which collect vast swaths of information and are used both to track and anticipate crime, often reflect cultural biases. In China, where there is little public scrutiny of these tools, they can be deployed to concentrate power and suppress legal and peaceful dissent.

Police departments in China often use software to track the locations of petitioners, according to a 2023 report from China Digital Times. This common practice, called “petitioner interception,” occurs when local authorities try to stop “citizens with grievances” from reaching the capital to file complaints to central authorities against them. There’s even precedent of forcing petitioners into mental health hospitals, which has led to the phrase “to be mentally-illed” (被神经病), or institutionalized against one’s will.

Police can even use GIS to track and scrutinize those labeled “persons of interest” for their religious affiliation, history of mental health hospitalization, or status as migrants — including citizens who haven’t committed any prior crimes.

In Nanjing, a city whose mapping system was designed by Luokung subsidiary Super Engine Technology Co., millions of vehicles travel highways, streets, and bridges each day.

In an interview published on Sohu, Gao Huiwu, the East China regional director of Super Engine, boasts that the Nanjing operation — designed to find the proverbial needle in a haystack — processes “more than 300 million vehicle position data generated every day.”

Part of this technology, Huiwu explains, allows police departments to store information about a vehicle’s movement, tracking and replaying the trajectory of suspicious vehicles. As cars and trucks weave through the city, police officials watch on — identifying license plates, pulling up data on vehicle owners, and using this information at their discretion.

Will These Chinese Surveillance Companies Be Delisted From the Nasdaq?

The U.S. has already acted against several Nasdaq-traded tech companies with ties to China’s public security and surveillance apparatus.

In 2019, the White House added companies like Hikvision, SenseTime, and Megvii to the U.S. entity list for their role in enabling human rights violations, particularly in Xinjiang. In 2021, the White House added additional companies to this list and barred them from receiving American investment or trading on U.S. markets.

The White House said, “The use of Chinese surveillance technology outside the PRC,” and its use “to facilitate repression or serious human rights abuses, constitute unusual and extraordinary threats.”

In recent years, Datasea, Taoping, and Luokung have nearly been delisted several times for issues related to low stock prices and market capitalization.

In December 2022, Datasea’s market value fell below the Nasdaq minimum for 30 days. In January 2024, Datasea was forced to enact a one-for-fifteen reverse stock split to avoid delisting when its shares fell below the $1 minimum. After revenue growth in 2024 and projected growth for 2025, Datasea is trading at over $2 as of January 2025.

In July 2023, Taoping was forced to enact a one-for-ten reverse stock split when its shares fell below the $1 minimum. In June 2024, Taoping received a Nasdaq warning when its share price again dipped below the minimum; the company has until June 2025 to regain compliance. As of January 2025, Taoping is still trading below $1.

In October 2024, Luokung received notice from Nasdaq that the company had failed to meet the minimum stockholders’ equity; Luokung was asked to submit a compliance plan by December. If Nasdaq accepts the plan, they may grant Luokung until April 2025 to regain compliance.

There is precedent for withdrawing these companies’ ability to list on the Nasdaq, not only due to their persistent financial challenges but for their connections to public security.

The U.S. Department of Defense previously put Luokung on a list of Chinese Communist military companies (CCMCs) barred from trading on the Nasdaq.

In 2021, Luokung was briefly delisted, but the decision was revoked in May 2021, after a U.S. judge suspended the DoD’s investment ban. Luokung’s ability to trade on the Nasdaq significantly influenced its market value; when the Nasdaq withdrew its delisting decision, shares of the company shot up almost 20%.

“The Chinese government is committing crimes against humanity,” Babur Ilchi, program director at the Campaign for Uyghurs, told Hunterbrook. “Companies that have provided advanced surveillance tools to continue doing this have made themselves complicit.”

Months before Ayup’s arrest, he was stopped at a checkpoint and questioned. As police interrogated him, Ayup realized they had collected information about everything from his recent visit to a friend to an email he had received from the Canadian embassy. Once he was arrested, police officials videotaped him walking, recorded him reading, and asked him to smile on camera. Ayup now realizes officials were gathering more biometric data to add to his file — data that could ultimately be harnessed to send him back to prison, or an internment camp.

The vicious cycle of surveillance and imprisonment led Ayup to flee to Norway, where he now lives with his family. For those unable to leave, Ayup said, “This surveillance technology makes people prisoner, even when they are living outside.”

UPDATE: This article was updated to reflect the fact that USPS resumed package shipments on February 5th.

Authors

Julia Case-Levine is a journalist, writer, and podcast producer based in Brooklyn. She has produced Signal-Award winning podcasts for Campside Media, and has written for The Nation, Bookforum, Quartz and elsewhere. She has a BA in History from Princeton University and an MA in Journalism from New York University.

Coby Goldberg is a law student at the University of Chicago. He was previously a Senior Analyst focused on China’s global business interests at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS). His work has been covered by CNN and The South China Morning Post, and has been published in Foreign Policy and the L.A. Review of Books.

Editor

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.