Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, our affiliate Hunterbrook Law and the litigation firm Slarskey LLP are investigating potential claims based upon Hunterbrook Media’s reporting. You may contact them regarding any rights you may have at ahollander@slarskey.com.

After Hunterbrook Media published an investigation into LGI Homes ($LGIH) — exposing the company’s predatory sales tactics aimed at low-income shoppers — multiple former sales employees reached out to confirm key aspects of our reporting and offer additional details. One, seeking anonymity because of retaliation concerns, shared LGI’s highly guarded sales training manual, a 261‑page internal document codifying the company’s coercive sales playbook in gritty detail. The findings are alarming:

- The manual directs sales agents to do the work of mortgage loan originators — a role they need a license to play — as part of LGI’s pressure-driven sales strategy: The sales manual instructs sales agents to, among other things, pull customer credit reports, review income and debts, counsel customers on credit and mortgages, and prequalify borrowers on their first visit to accelerate their path to a home purchase — all activities typically performed by licensed mortgage loan originators. In some states, including LGI’s home state of Texas, unlicensed mortgage activity is a criminal violation.

- LGI funnels ineligible borrowers onto what one source called a “hot list” and uses credit counseling to boost their scores: In practice, that counseling reportedly often amounted to telling buyers to open a high-fee credit card and start using it. Former sales employees said they were uncomfortable being tasked with serving as unlicensed credit counselors to help buyers improve poor credit scores.

- Potential steering to affiliated lender: LGI customers told Hunterbrook that sales agents represented LGI’s affiliated lender as the only permissible lender — a potential violation of federal law, if true. Former employees also confirmed that they were trained to position the affiliated lender as the only option. The manual itself says that sales agents are expected to channel at least 90% of customers toward an affiliated lender.

- Sales agents are taught to manipulate, coerce, and pressure buyers: The manual provides a step-by-step guide on manipulation tactics sales agents should use to control the customer experience and turn a “no” into a “yes.” Former sales employees described a sales philosophy that preys on vulnerability akin to the time-share model. One said LGI’s sales techniques were based on the premise that “your clientele is stupid and it’s your job to be smarter.”

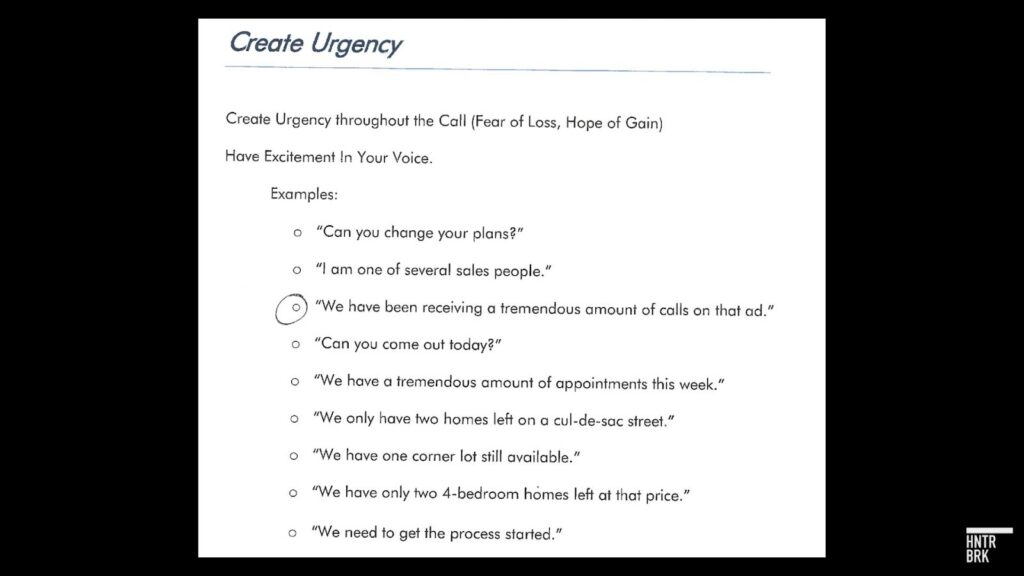

- Misleading claims and a false sense of urgency: The manual instructs sales agents to manufacture urgency using a scripted set of claims that are not universally true. A former sales manager and a homeowner said LGI placed “Sold” signs on homes not yet sold to mislead potential buyers about the desirability of properties.

- Ads to Target Renters Not Looking To Buy: Former employees said that many people who ended up in an LGI office believed they would be renting and were pressured into buying a home instead. The manual confirms that sales agents are directed to seek leads within Craigslist sections specifically designated for renters in order to convert them into buyers.

- Selling false dreams to consumers and employees alike: Former employees said that ethical concerns about how LGI’s tactics were harming customers were routinely ignored. They also told Hunterbrook about an alleged incident of abuse, being pitted against each other, and false promises that they would make millions of dollars.

Every new sales agent at LGI Homes receives the manual — tagged with their name on each page to prevent leaks, fiercely guarded by legal threats. The company calls it the “LGI Way.” Former employees we spoke with see it as something else: a blueprint for exploitation.

The 261-page document was voluntarily provided to Hunterbrook by a former sales agent, who reached out after seeing our earlier reporting on LGI’s predatory sales practices. That investigation found foreclosure rates among LGI customers were four times the national rate for comparable mortgage borrowers.

“Wait until you see it in black and white. When you see the sales techniques, you’re going to be like, ‘there’s no way,’” the former sales agent said, referring to the manual.

The “bible,” as the former sales agent called it, provides step-by-step instructions on what to say and how to treat customers to convert them into homebuyers on their first visit to the office. LGI sales agents are expected to study every line, memorize them all, and master the techniques before they can become full-fledged representatives of LGI, according to the source.

The manual details a process that former employees confirm is designed to pressure low-income shoppers into purchasing homes they cannot afford. It also directs sales agents to employ tactics that could violate federal and state consumer protection laws.

One such tactic: Instructing sales agents to act as loan originators and offer financial advice for which they are generally unqualified — possibly illegally, based on Hunterbrook’s review of federal law and prior regulatory actions.

The manual also teaches psychological techniques designed to manipulate customers who say “no,” providing scripted responses aimed at reversing objections based on the idea that “people often reject what they need the most.”

It offers fill-in-the-blank scripts for creating false urgency about limited inventory.

With each step, the explicit goal is always to keep LGI in control. “THEY feel in command, but WE are,” it states.

These are just a few examples of the tactics outlined in the manual.

Barry Hersh, clinical professor of real estate at New York University, told Hunterbrook that using questionable lending practices and targeting customers with low credit was reminiscent of the tactics that led to the financial crisis in 2008.

“It seems to me they’re repeating what was done from 2002 to 2007 until the market collapsed,” he said.

The manual describes a commitment to “integrity” and “ethical behavior.” Its contents — and our interviews with eight former employees and homeowners — tell a different story.

LGI did not respond to a detailed request for comment by the time of publication.

Sign Up

Breaking News & Investigations.

Right to Your Inbox.

No Paywalls.

No Ads.

LGI Directs Sales Agents To Conduct Mortgage Activity — A Potential Criminal Violation in LGI’s Home State

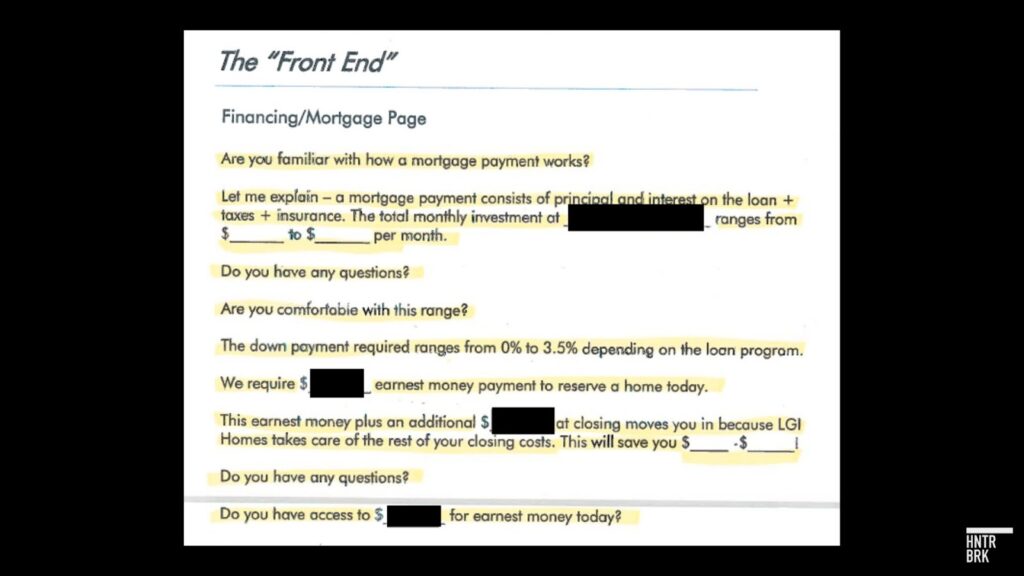

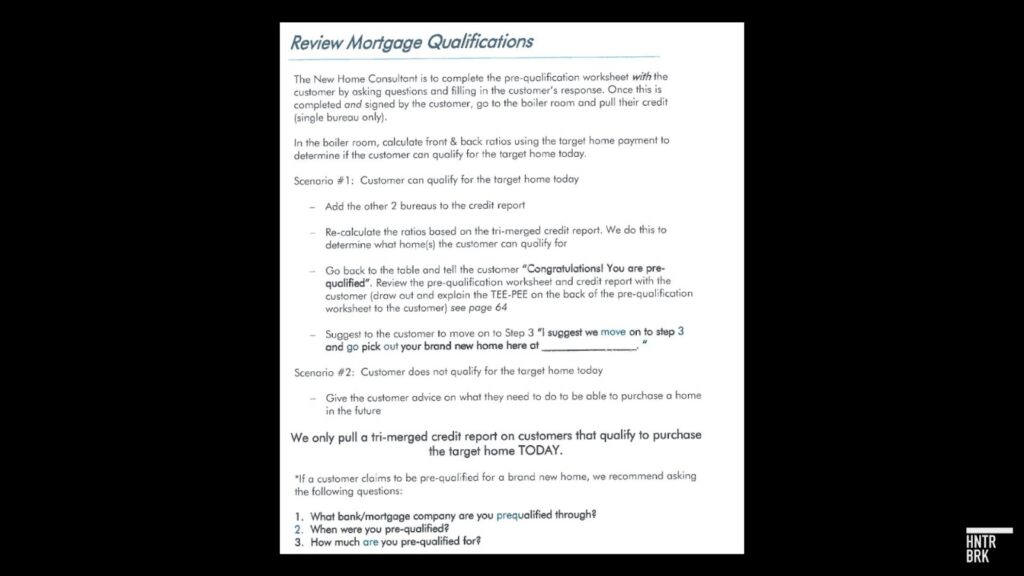

LGI’s sales manual spells out a strategy in which sales agents explain to customers how a mortgage works, collect detailed financial information about the customer, pull credit, “give the customer advice,” and, notably, “pre-qualify” customers for a mortgage.

According to former sales employees, however, sales agents were typically not licensed as mortgage originators, and the manual itself explicitly tells sales agents, “You are not in the mortgage business.” Hunterbrook found additional information that suggests LGI sales agents are not licensed as loan officers. In its latest 10-K, LGI said, “Our information centers are … generally staffed by two to four sales professionals who are supported by a dedicated loan officer.” However, according to a mortgage officer data aggregator, there were only 37 loan officers associated with LGI nationwide, compared to 141 communities in active sales as of November, staffed by an estimated total of 423 sales agents. (Hunterbrook derived that estimate based on LGI’s claim that there were 141 communities as of November, and that each community’s sales office was staffed by two to four — or an average of three — sales agents.) Additionally, according to the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System database, two of LGI’s 44 sales agents in California held a license as a loan originator, but none were sponsored by LGI — a requirement for engaging in the activities of a mortgage loan originator on behalf of LGI. Thus, these activities could run afoul of laws against unlicensed mortgage activity, a criminal violation in certain states such as LGI’s home state of Texas.

State and federal laws generally require real estate brokerage or sales activity and mortgage origination activity to be conducted out of two separate and appropriately licensed entities, even if there is common ownership of both operations. The separation exists to ensure consumers receive accurate, independent mortgage advice from licensed providers, and to protect borrowers from being steered or pressured into unsuitable financing.

On the surface, LGI appears largely to be organized in compliance with these rules: Its sales arm — licensed as a real estate sales organization — is supposed to sell homes, and its affiliated mortgage broker, LGI Mortgage Solutions, employs licensed mortgage loan originators who handle the financing.

In a nod to this legally mandated distinction, the manual alerts sales agents, “You are not in the mortgage business. It is your job to sell the homes,” right before it directs them to jump headfirst into that very business.

The sales agent is instructed to introduce the customer to the concept of a mortgage in a way that appears to highlight the potential benefits and mask the risks. Repeatedly, the sales agent is trained to mischaracterize the monthly payments, including interest, taxes, and insurance, as an “investment.” Calling monthly mortgage payments an “investment” could leave the customer with the false impression that a large portion of the monthly payment — specifically the amount tied to interest, taxes, and insurance — constitutes an “investment,” when in fact these items are a cost of homeownership.

Then the sales agent is told to describe to the customer the different down payment amounts related to various loan programs offered by LGI’s affiliated lender. The script even includes an opportunity for the customer to ask questions about mortgages, the answers to which the sales agent may be unqualified and unlicensed to answer.

The manual also directs sales agents to complete a prequalification worksheet with the customer, collecting the shopper’s name, social security number, and income, the address of the target home, the property’s estimated value, and the proposed amount of a mortgage loan — the six elements of what officially defines a mortgage application. By following the script, the LGI sales agent, even if unlicensed as a mortgage originator, has accepted what likely amounts to the submission of a mortgage application. The official interpretation of the TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure (TRID) rule lists the following as the six elements of a mortgage application: the shopper’s name, income, address of the target home, property’s estimated value, and proposed amount of a mortgage loan.

The Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act, commonly known as the SAFE Act, Throughout this article, “SAFE Act” refers specifically to the federal Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008, which established licensing and registration standards for residential mortgage loan originators, and not to other federal or state laws that use the same acronym. stipulates that an individual must be licensed as a mortgage loan originator if they “take a residential mortgage loan application,” even if the individual does not actually verify the information or originate the loan.

In fact, under federal law, the collection of the six components of a mortgage application triggers a requirement for the delivery of a loan estimate within three days.

The SAFE Act also defines offering mortgage loans as licensed mortgage origination activity, including verbal offers — something that the manual directs the sales agents to do next.

The sales agents are then told to “go to the boiler room and pull their credit,” and if all goes well, return saying, “Congratulations! You are pre-qualified.”

“These people have never been approved to buy a home. So, there’s so much excitement for it, for you to go out and show them this house,” a former sales agent explained.

States have enacted laws and regulations parallel to the federal SAFE Act. In Texas, the state finance code that governs mortgage companies defines a “residential mortgage loan originator” as an individual who for “the expectation of compensation or gain” takes a “residential mortgage loan application” or “offers the terms of a residential mortgage loan.” Texas law also provides that unlicensed activity may be a criminal violation and can result in civil fines and private liability. The Texas Department of Savings and Mortgage Lending reached regulatory settlements related to this rule, e.g., Texas Department of Savings and Mortgage Lending v. Fred David Rich, VAH Investments of Texas, Inc. d/b/a Coastal Properties, et al., where it was found that Fred David Rich and affiliated businesses engaged in the sale of real estate were simultaneously and unlawfully engaged in unlicensed residential mortgage origination activity within the State of Texas.

State regulatory actions on the basis of unlicensed mortgage activity are common. As recently as October, Hawaii, Idaho, Oregon, and Texas settled with E Mortgage Capital for $669,000 in part because “E Mortgage engaged in unlicensed activity by allowing unlicensed mortgage loan originators … to conduct origination activity.”

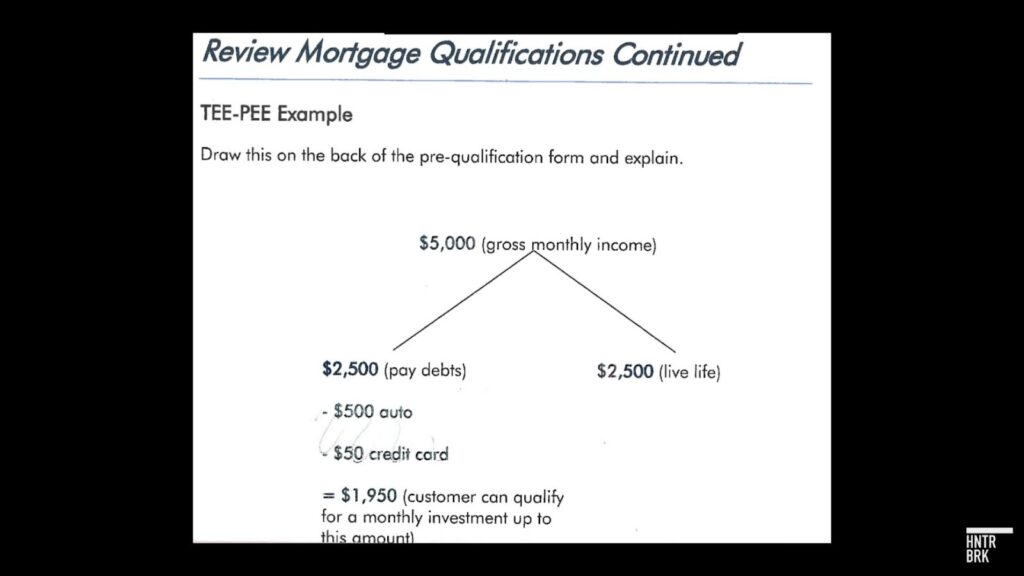

The potential harm of unlicensed mortgage activity to a consumer becomes apparent in the next step in the manual: The sales agent is instructed to draw a simple diagram to assure the customer that they really can afford the home that they want to buy. If the estimated mortgage payment plus debts such as auto and credit card bills are less than or equal to 50% of their self-reported gross income, the customer can afford the mortgage, the manual says.

While maximum debt-to-income ratios vary by loan type and the overall profile of the borrower, Fannie Mae, a government-backed company that buys mortgages from lenders, generally sets the DTI limit to 36% for conventional loans but allows for some exceptions for higher DTIs — not to exceed 50% — with strong compensating factors. FHA loans — government-sponsored loans designed for lower income borrowers — can allow debt-to-income ratios up to about 55%, but only for borrowers who meet stronger credit or financial criteria. widely used affordability standards, which come from federal mortgage-underwriting rules, The Federal Housing Administration’s Handbook 4000.1 establishes a 31/43 DTI benchmark for manually underwritten FHA loans (4000.1, II.A.5 “DTI cannot exceed 43% without compensating factors”). generally expect total debt obligations — including not just mortgage payments but also any other debt obligation such as auto loans, credit cards, student loans, or child support — below roughly 36%–43% to avoid overstretching the borrower’s budget. These same ratios are echoed in Consumer Financial Protection Bureau consumer guidance and in longstanding FDIC advice on prudent debt-to-income levels.

The diagram also allocates the other 50% as money available to “live life,” without accounting for federal and state income taxes, Social Security and Medicare taxes, retirement contributions, and other fixed expenses like insurance, HOA fees, and utility bills. Taken together, this gives a misleading impression of affordability, ultimately offering what could be an unsustainable path for borrowers.

As the customer leaves the LGI office to tour homes, the agent hands them a “sold” sign and delivers a reassuring line: “I am a very optimistic person and believe we have the right home for you.”

Numerous regulatory actions

In the Matter of Kelly Mortgage Inc., Tracy Kelly is a regulatory action brought by the Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services, Division of Financial Regulation where it was found that representatives of Cal-Am Properties, Inc., some of whom were unlicensed or only licensed as a real estate broker, unlawfully conducted mortgage origination activities on behalf of Kelly Mortgage.

Texas Department of Savings and Mortgage Lending v. Fred David Rich, VAH Investments of Texas, Inc. d/b/b Coastal Properties, et al. is an action brought by the Texas Department of Savings and Mortgage Lending, where it was found that Fred David Rich and affiliated businesses simultaneously and unlawfully engaged in both real state sales and unlicensed residential mortgage loan origination activity in the state of Texas.

In the Matter of Loansnap, Inc. d/b/a LoanSnap NMLS #76967 is a regulatory action brought by the Connecticut Banking Commissioner where it was found that Loansnap engaged the services of at least four individuals who were not licensed to act as mortgage loan originators. Specifically, Loansnap used these unlicensed individuals to accept applications and negotiate loan terms in violation of the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act and other state laws.

show that the activities described in the manual are treated as mortgage origination activity and require licensing by the relevant mortgage regulator.

A former sales manager often worried about regulators catching wind of LGI’s tactics. “We don’t have the licenses to pull credit to see their financials,” they said. “That’s an NMLS NMLS stands for the Nationwide Multistate Licensing System/Nationwide Mortgage Licensing System, which credentials mortgage loan originators and other financial professionals. thing … I’m not supposed to be touching this stuff.”

They added, “I can’t believe nobody’s come in here and shut this down.”

“I can’t believe nobody’s come in here and shut this down.”

– Former LGI sales manager

The former manager also noted that, unlike LGI, other homebuilders strictly followed policies prohibiting sales employees from reviewing a customer’s financial information.

“Every other builder I’ve worked for does things by the book. Just normal industry standards. You guys are here to sell homes, that’s what your license is for.”

Unqualified Credit Repair Services To Edge Low-Credit Shoppers to Mortgage Eligibility

The LGI manual also instructs sales employees to identify customers whose credit scores fall short of qualifying immediately for a loan and nudge them over the threshold with a bit of “credit counseling.” Federal laws may prohibit unlicensed professionals from providing such services, however.

Credit counseling, like mortgage origination, is a tightly regulated activity only licensed professionals are permitted to perform because it involves providing sensitive financial advice to consumers that can materially affect their financial health. Federal laws like the Credit Repair Organizations Act exist to prevent businesses from giving misleading advice or steering consumers toward harmful financial decisions.

More than 70% of LGI’s leads enrolled in the “credit remediation program” because of their “questionable” credit, a former manager estimated.

One manager recalled being trained to first “get them to trust you.” Then sales employees were told to go over their credit reports, review financials, and even offer advice such as telling customers to sell their car to boost their score.

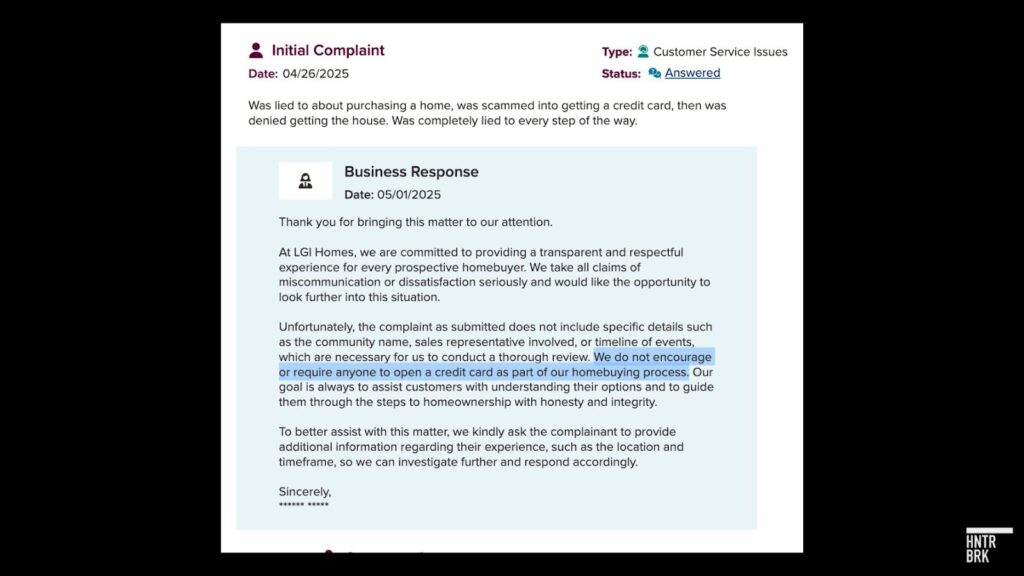

Among the most questionable advice? Telling customers to open a very high-fee credit card.

A customer complaint in April on the Better Business Bureau website mentioned being “scammed” into getting a credit card as part of the purchasing process.

LGI’s official response: “We do not encourage or require anyone to open a credit card as part of our homebuying process.”

That’s not what the manual says.

An entire section of the sales manual lays out how agents can encourage customers to sign up for a First Premier credit card as a credit repair strategy. LGI specifically recommends First Premier because, unlike most credit card companies that report to the three major credit bureaus within 90 days, First Premier reports to all three in less than 10 days, the manual claims. LGI asks sales agents to quickly follow up directly with First Premier to inquire about the status of the customer’s credit card application, potentially in violation of privacy and consumer protection law. Under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), “application status” counts as personally identifiable information because it relates to the consumer’s financial transactions. As a result, sharing this information with a nonaffiliate (LGI does not appear to be formally affiliated with First Premier) could violate privacy regulations.

“We have seen scores increase from 0 to 50 points with this scenario,” the manual notes.

Opening a First Premier credit card might not be as simple and benign a strategy as the LGI manual implies.

With one of the highest interest rates in the industry, As of November 2025, the average APR for all new credit cards is 24.04%. First Premier’s credit card APR is 36%. First Premier’s other consumer-unfriendly policies like multiple ongoing fees, low limits, and a 25% credit-limit increase fee could make the credit card a risky option for many shoppers.

First Premier has a checkered history. In 2007, the company paid $4.5 million to settle an investigation by the New York Attorney General into deceptive marketing to subprime consumers. In 2010, First Premier was awarded the dubious honor of “worst credit card in America” by Consumer Reports. In 2014, First Premier sued a consumer credit card comparison site for refusing to take down data comparing the rates and fees charged by First Premier with those of its peers. And as recently as 2020, well-known credit card review site The Points Guy gave the card a 1.5 star rating, noting “the many fees that it charges and how confusing they can be, even to someone accustomed to reading credit card terms and conditions.”

“LGI never talks about the downside of anything,” a former sales agent said, referring to the fact that they were trained to not discuss any issues with the First Premier credit card.

Kit McQuiston, who teaches real estate development at New York University, told Hunterbrook that while it is hard to prove when a sales agent crosses a legal boundary, red flags include offering financial advice while not providing alternatives, overriding objections, and not discussing drawbacks or dangers with clients.

“Sometimes companies just talk about the benefits and not the risks. And if that’s not balanced and if you’re giving financial advice and you’re not representing that — you’re an unlicensed person giving financial advice — then I would assume you could get in trouble for that,” McQuiston said.

A former sales manager described the process of reviewing and offering financial advice as not only uncomfortable but possibly illegal. “We are by no means credit counselors,” they said, and added, “We’re just supposed to be selling houses.”

One homeowner, who purchased an LGI home three years ago, dodged LGI’s credit card suggestion but said, “We definitely did not have the proper information in order to make an informed decision.”

They added, “They prey on first-time homebuyers and younger families who don’t have much experience in buying a home.”

Potential Steering to Affiliated Mortgage Service

In addition to encouraging unlicensed mortgage and credit advice, LGI also appears to be instructing its sales reps to steer buyers to the company’s affiliated lender — regardless of whether that delivers the best outcome for the buyer. The manual tells agents that “all customers should obtain their mortgage with LGI Mortgage Solutions” and sets a goal to achieve a 90% capture rate — describing this as a “mission critical task.”

But that goal risks directing sales agents to violate federal law once again. When LGI channels customers to its affiliated lender, this action could be considered a “referral” to a “settlement service provider” under the Real Estate Settlements Procedure Act, or RESPA. RESPA mandates that “[n]o person making a referral has required any person to use any particular provider of settlement services,” subject to narrow exceptions.

While other national builders encourage buyers to go with their affiliated lender, they typically do so by offering competitive incentives. Homebuilders D.R. Horton and Lennar, for example, have been making headlines since last year with dramatic incentives, including mortgage rate buy-downs, amid a continued housing downturn.

LGI, on the other hand, had openly touted its refusal to budge from its longstanding policy of not offering incentives — only beginning to offer them in the last two quarters this year as market conditions further tightened.

A former LGI sales manager confirmed that sales agents were expected to employ the tactics described in the manual to convince customers to use the affiliated lender: “We had to steer everybody toward them. So, it wasn’t really an option. People couldn’t come in and go, ‘Oh, I’m working with Wells Fargo.’ No, you’re not anymore.”

Multiple LGI customers confirmed that was their experience as well. Bri Jackson, who purchased a home with LGI in 2020, told Hunterbrook that LGI’s affiliated lender was presented as the “only option” if she wanted to purchase a home with LGI.

“It was like a one-stop shop. We sell, we finance you here, and that’s how that works,” she said. “This is the only way you get this house, through this company.”

Another LGI homeowner, Latoya Jackson, echoed those sentiments. “They kind of pushed that,” she said, explaining that she had been pre-approved through three other lenders but was told she could close faster with LGI’s lender.

LGI’s possible incentives for steering may be twofold. First, there are financial gains from mortgage origination that typically drive companies to steer borrowers to their preferred lenders. Also, for LGI, it often comes back to one central theme: control. The manual indicates that customers obtaining their mortgage through their affiliated lender allows LGI to “control the transaction” and “control the customer experience.”

Psychological Manipulation Tactics

This emphasis on control weaves through various tactics outlined in the LGI manual, from giving loan advice to creating a sense of urgency.

Former employees told Hunterbrook these tactics were used on vulnerable groups, including first-time homebuyers with little or no experience in real estate transactions.

The manual provides a highly detailed script for LGI’s sales agents to take control and peel away every possible objection by a customer, from the beginning of their first interaction until the customer ultimately signs the contract. The moment a customer calls LGI to inquire about an ad, they unknowingly become part of the script.

The phone training section of the manual is designed to “create urgency throughout the call” with “Fear of Loss, Hope of Gain” in order to pressure potential customers to come into the LGI office as soon as possible. The script directs sales agents to “take control of the call.”

The script continues to the next steps, each spelled out in painstaking detail, from what brand of drinks to offer customers who arrive in the LGI office, to what lines to say, in what order.

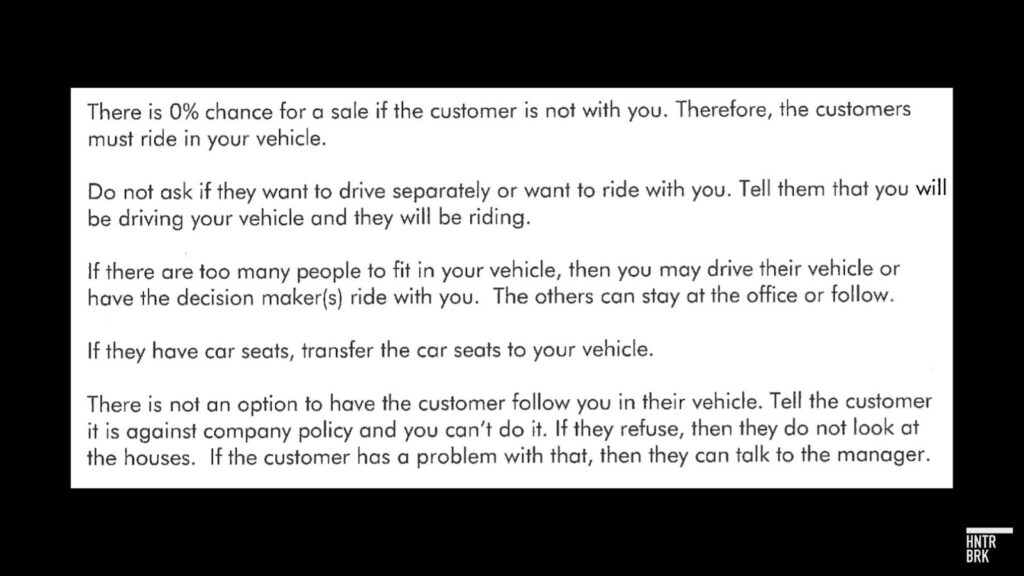

In a particularly stunning example of the company’s emphasis on control, the manual tells sales agents that customers who want to view homes are forbidden from driving their own vehicles.

“Tell them that you will be driving your vehicle and they will be riding,” it says. “If they have car seats, transfer the car seats to your vehicle.”

If there are too many people to fit in the agent’s vehicle, the agent must drive the customer’s vehicle, according to the manual.

If the customer refuses these options, “then they do not look at the houses,” the manual says.

Another key theme throughout the manual is that a customer’s objection is just an obstacle that must be overcome.

“A ‘NO’ OR HEAVY OBJECTION IS SIMPLY NOTHING MORE THAN A ROADBLOCK TO THE SALE,” it goes on. “We must have the ability to meet the ‘No.’” The manual then lays out a detailed diagram prescribing responses sales agents should use to reverse a “no.”

Customer concerns are treated as insignificant — they can be overridden with a bit of psychological maneuvering. A section of the manual distills a customer’s decision to buy a home simply as a mindset change, and teaches sales agents how to help their customers “work through the discomfort” of that change.

“People often reject what they need the most,” the manual declares.

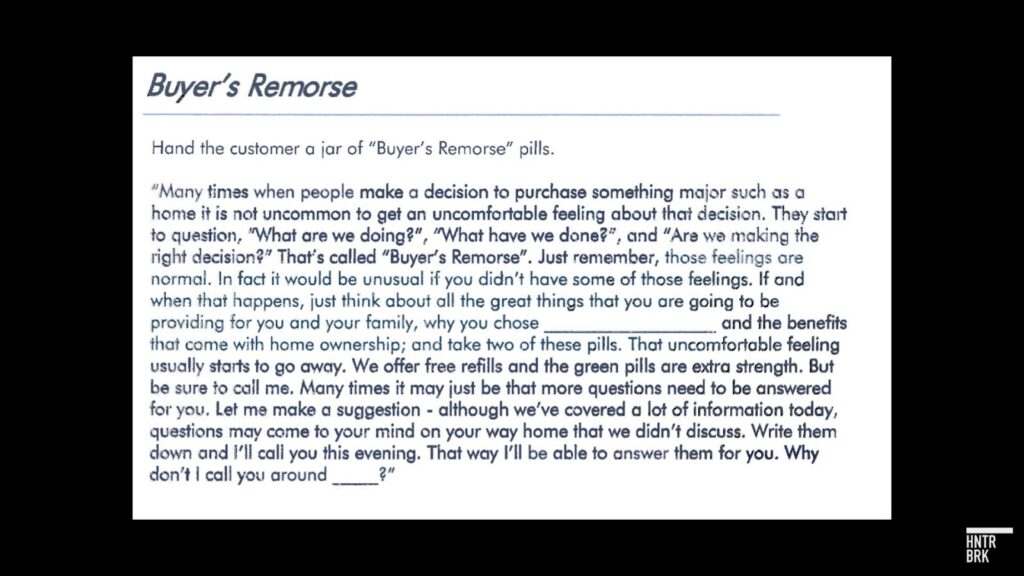

The manual even prepares sales agents to handle buyers having second thoughts after finding themselves signing off on perhaps the biggest financial decision of their lives.

A dedicated section titled “Buyer’s Remorse” directs sales agents to tell customers expressing second thoughts about their home purchase that “those feelings are normal,” and instructs the agents to redirect the conversation to “anything besides the house,” such as kids or weather.

“Just think about all the great things that you are going to be providing for you and your family,” the sales agents are expected to say, before offering jelly beans it refers to as “buyer’s remorse pills.”

“We offer free refills and the green pills are extra strength.”

“We would lie to people all the time.”

The manual teaches agents to make dubious, off-the-shelf marketing claims to influence a buyer’s decision — claims that could amount to fraud, according to Hunterbrook’s review of federal and state regulations.

For example, the manual declares in big, bold letters: “CREATE URGENCY!”

A worksheet offers pick-your-own statements sales agents can use to create urgency — regardless of whether those statements reflect reality. “We have been receiving a tremendous amount of calls,” reads one example. “We have only two 4-bedroom homes left at that price,” reads another, and, “We only have two homes left on a cul-de-sac street.”

“We would lie to people all the time,” a former manager told Hunterbrook.

“We would lie to people all the time.”

-Former LGI Sales Manager

As part of creating urgency, LGI sales agents — many of whom come from the “mattress industry,” according to Hunterbrook’s last investigation — were told to put “Sold” signs on homes that had not sold before weekend tours, the former manager said. Such tactics could potentially violate federal and state consumer protection laws, if not amounting to outright fraud.

“In general, actionable fraud occurs when one party knowingly misrepresents a material fact, another party reasonably relies on it, and that reliance results in damages,” real estate lawyer Todd McLoughlin told Hunterbrook.

McLoughlin said, however, that laws vary by state, and there is often difficulty in proving that misrepresentations are material to a customer’s buying decision.

Booking Sales with Ineligible Buyers To Boost Orders

Amid continued weak demand for its homes, there may be another reason LGI goes to such lengths to get customers to sign the contract, regardless of whether they can actually qualify for a loan and close on the home: to boost order numbers as reported to shareholders.

“They are running credit and approving pretty much anybody they can and then they’re falling out of contract later,” said a former sales agent.

One motive for booking orders from as many potential buyers as possible could be to create the appearance of strong business performance, even if many contracts never close. On LGI’s most recent earnings call on November 4, 2025, CEO Eric Lipar emphasized a 44% year-over-year increase in net orders, and LGI’s stock rose about 10% that day — despite the fact that sales had fallen 39.4%. Net orders account for all purchase agreements signed, not homes that actually closed.

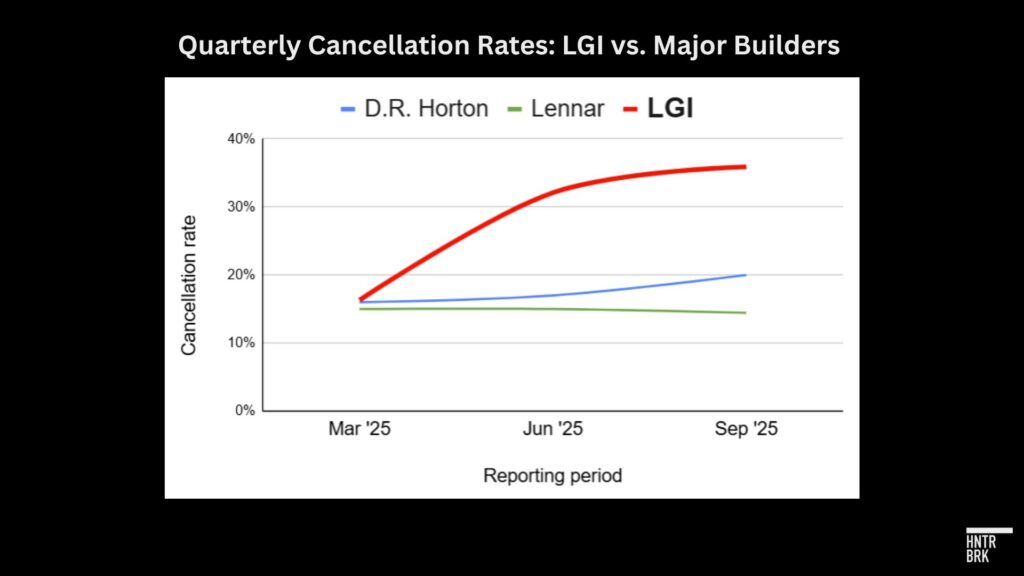

LGI’s climbing cancellation rates suggest, however, that many of the net orders are not materializing into sales — even with LGI’s systematic efforts to bring up buyers’ credit scores. On the call, Lipar admitted that the loan ineligibility of buyers was a key reason for difficulties in closing the sales, telling investors that buyers may need additional time to “make modest improvements in their credit.”

Although LGI apparently did not publish the figures for the third quarter of 2025, Hunterbrook’s calculations pointed to an approximate cancellation rate of 35.9% — up from 32.1% in the second quarter, and 16.3% the quarter before.

In comparison, the cancellation rates for leading home builders D.R. Horton and Lennar in the third quarter were 20% and 14.5%, respectively.

And when LGI’s credit repair program alone couldn’t convert the order into an actual sale, sales agents were directed to try other methods, according to a former sales agent.

Confirming Hunterbrook’s earlier reporting, the former sales agent mentioned they were trained to find all possible cosigners. “Oh, you can’t afford the house? Maybe we can just put it under your son,” they said as an example of the tactics LGI would tell them to employ.

Looking To Rent, Pressured To Buy

Hunterbrook’s earlier reporting revealed how LGI sends flyers to renters with unrealistically low monthly prices and phrases like, “Why rent when you can buy?”

According to a former sales manager, many of the potential customers did not understand that LGI was selling and not renting homes. “It was kind of a gray thing and we all knew,” they said.

And while LGI does offer rental properties, former employees said LGI intentionally posted ads within Craigslist’s rental sections to attract renters, bring them to the sales office, and pressure them to buy a home instead.

“A lot of people would say ‘I thought these houses were for rent’ and then we had a whole phone script to get them to come in for an appointment to see if we could get them to qualify to buy a home,” a former sales manager explained.

A former sales agent said official policy was to “never acknowledge the fact that you’re talking to somebody who’s looking to rent. Just get them in the door.”

Another former manager confirmed this practice, telling Hunterbrook that sales agents would try to convince people who viewed Craigslist “For Rent” ads to buy a home once they were in the LGI office. “Next thing you know, they’re filling out a pre-qual when they were just trying to rent a house,” they said.

False Dreams Sold to LGI Customers and Employees Alike

Much like the process with potential buyers, some sales employees were sold a mirage at first.

A former sales agent recalled their first week of training at LGI: They were flown out to Texas to the CEO’s mansion. The new agents were fed an elaborate dinner, and according to the former agent, were told by leadership, “You guys are going to make millions of dollars.”

A former sales manager recalled that on his cohort’s trip to the CEO’s mansion in Texas, they were welcomed into “the club” and told it was harder to get into than Harvard.

But once the initial welcome faded, a harsh reality surfaced about working at LGI, former employees recalled. Employees being pitted against one another. Barred from leaving the office for lunch breaks. Multiple former LGI employees described a scene where sales employees would race each other to get to the office first, because that’s who got the best leads. Like Glengarry Glen Ross, but in real life.

One former sales manager told Hunterbrook they were attacked by an executive, reported it, and were ignored.

Another former employee claimed that LGI’s policies encouraged agents to fight with each other over leads.

Repeatedly, former LGI staff described a sense of guilt at what they were doing to customers.

“It’s a really hard place to work if you have any sort of compassion for people,” a former sales agent recalled.

“You’re basically wrecking people’s lives,” another former employee said.

TreVon Encalade and his wife were among the customers affected by these tactics. They were first-time homebuyers with LGI in 2016, he said, “looking for somewhere to call our own.”

Encalade felt he had been misled throughout the process. “We were 23 at the time. So we didn’t really know what to look for, what questions to ask,” he said.

They were encouraged to go with LGI’s lender without discussion of other options. They quickly signed a purchase agreement.

“We just thought, okay, this is standard practice. So we just signed on a dotted line.”

Reflecting back on the process, Encalade summed up the experience: “Deception by omission.”

Authors

Michelle Cera trained as a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She completed her PhD in Sociology at New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. She has also served as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and innovative research methodologies.

Matthew Termine is a lawyer with nearly five years of experience leading the legal team at a mortgage technology company. In 2017, Matt was credited by the Wall Street Journal, among others, for identifying suspicious mortgage loan transactions that led to several successful criminal prosecutions, including that of a prominent political operative and the chief executive officer of a federally chartered bank. He is a graduate of Trinity College and Fordham University School of Law. He grew up in Old Saybrook, Connecticut and now lives in Brooklyn with his wife and three children.

EDITOR

Jenny Ahn joined Hunterbrook after serving many years as a senior analyst in the US government. She is a seasoned geopolitical expert with a particular focus on the Asia-Pacific and has diverse overseas experience. She has an M.A. in International Affairs from Yale and a B.S. in International Relations from Stanford. Jenny is based in Virginia.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.