Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $SOC at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

This article includes detailed analysis by a recent federal law clerk engaged to clarify the complex array of litigation involving Sable. Nothing here is legal advice. Other sections were reported by Hunterbrook’s reporters. Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to reach the reporting team.

Hunterbrook Media has reported on Sable since early 2024. These investigations have scrutinized Sable’s effort to restart a project responsible for one of the biggest oil spills in California history. The articles have been cited by Bloomberg, Politico, the Wall Street Journal, and several other publications. The findings were also cited in Santa Barbara’s decision to deny the transfer of key permits to Sable from Exxon, the pipeline’s prior owner. When Hunterbrook published its first article on Sable, the company had already delayed its launch timeline to Sept 2024. That launch has still not occurred as of Jan 2026. Sable is once again teasing an imminent restart. Here’s our reporting on why that remains a long-shot.

“It’s much harder to stop us once we’re in production than the status quo being off production,” Sable Offshore CEO Jim Flores told investors in a leaked audio recording newly obtained by Hunterbrook.

“And the big key thing is we don’t need to publicize.”

He added: “We’re keeping it strictly within the investment community.”

Flores was laying out a stealth strategy to restart the pipeline responsible for one of California’s worst oil spills — pump first, deal with regulators later. Once oil was flowing, he reasoned, it’d be harder for the state to shut him down.

“Then, if the judge wants to come in and do something crazy, the status quo is production.”

There were a few problems.

Among them: Flores needed approval from a range of California government authorities, including the California Coastal Commission (CCC) — which Flores criticized on the call for what he called its “eco-Nazi attitude.”

That call took place on April 15, last year. At the time, Flores said: “Our target is June 1 to start putting oil into 324, 325,” referring to Sable’s onshore Las Flores pipelines, formerly known as Plains Lines 901 and 903.

As of this January, the quiet restart Flores had promised investors still hasn’t happened — nine months after that audio recording and two years after the company initially said its project would be online.

In the meantime, with the pipeline still dormant, California has done what Flores seemed to fear: launching a wave of legal and regulatory attacks to keep it that way, putting a labyrinth in Sable’s path.

In other words, for now at least, it looks like the “eco-Nazis” are winning.

In a court appearance earlier this month, Sable’s lawyers confirmed the Exxon spinoff had not filled its pipelines — and conceded the company cannot restart while a preliminary injunction remains in place.

“This is costing us millions of dollars every day,” Sable’s attorney told Judge Donna Geck of the Superior Court of Santa Barbara County, pleading for an accelerated legal timeline.

Sable now pins its hopes on the Trump administration, which only has limited authority over the project.

In December, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) asserted jurisdiction over one aspect of the pipeline’s approval process: safety. PHMSA approved that aspect of the restart plan despite California’s objections. In court, the company trumpeted this as a breakthrough.

But as evidenced by Sable’s failure to fill its pipeline, federal backing isn’t enough. PHMSA’s authority does not cover regulatory areas beyond safety, such as mitigating coastal effects in California. Those aspects are still delegated to state authorities.

In recent weeks, Hunterbrook has reviewed the relevant laws, precedents, and court proceedings — speaking with experts in state and federal environmental regulations. This reporting has revealed that Sable, whose only asset is this project, faces at least seven independent legal barriers to restart, several of which could keep the pipeline offline indefinitely.

Without additional funding, Sable appears set to run out of cash before it clears them all, if it ever does. The company has an estimated less than $100 million in the bank if spending hasn’t meaningfully slowed in recent months.

“There’s still a lot of legal obstacles in the way and a lot of opportunity for opponents to try to tie things up,” said Deborah A. Sivas, the Luke W. Cole Professor of Environmental Law at Stanford Law School.

Those remaining barriers include:

- A federal consent decree put in place after the 2015 oil spill. The decree explicitly requires approval from California’s Office of the State Fire Marshal (OSFM), not the federal PHMSA, before restart can occur. The requirement remains legally binding and enforceable by the California Attorney General, whose office has previously sued Sable. Earlier this month, the AG office said it was exploring its options to defend state jurisdiction over Sable’s pipeline. Under significantly changed circumstances, a consent decree can be updated by requesting modification from the federal court that entered it. But Sable has not begun this process — presumably because case law states the executive branch can’t unilaterally create a change that justifies departure from the terms of an agreement to which it bound itself.

- A court injunction requiring Sable to obtain “all necessary approvals and permits” before restarting the pipeline. That includes approval from OSFM, which Sable has conceded it does not have. At the next hearing in the case where the injunction was entered, scheduled for Feb. 27, the court will consider Sable’s argument that federal law preempts state authority to regulate the pipeline — including the injunction — now that PHMSA has claimed jurisdiction. According to our analysis, the active consent decree will make it hard for the judge to side with Sable that it no longer needs to obtain approval from OSFM, as OSFM still has authority under that agreement. The California AG office, who represents parties both to this case and to the consent decree, has stated it is exploring its options to protect OSFM’s authority, indicating that reconsideration of the injunction could be a drawn out process.

- A second court injunction surrounding coastal work. Judge Thomas Anderle of the Superior Court of Santa Barbara is barring Sable from any “development” activities on the pipeline. Excavation. Grading. Pipeline infrastructure work. Placement of materials on the seafloor. The injunction lasts until Sable obtains Coastal Act authorization from the CCC. Without the ability to maintain the pipeline, operating it would mean massive liability risk, including potentially for Exxon. Sable relies on Exxon’s permits in the absence of its own. Sable appealed this injunction, with briefing completed on Jan. 9. A hearing on a separate motion for reconsideration in the trial court is set for Feb. 18.

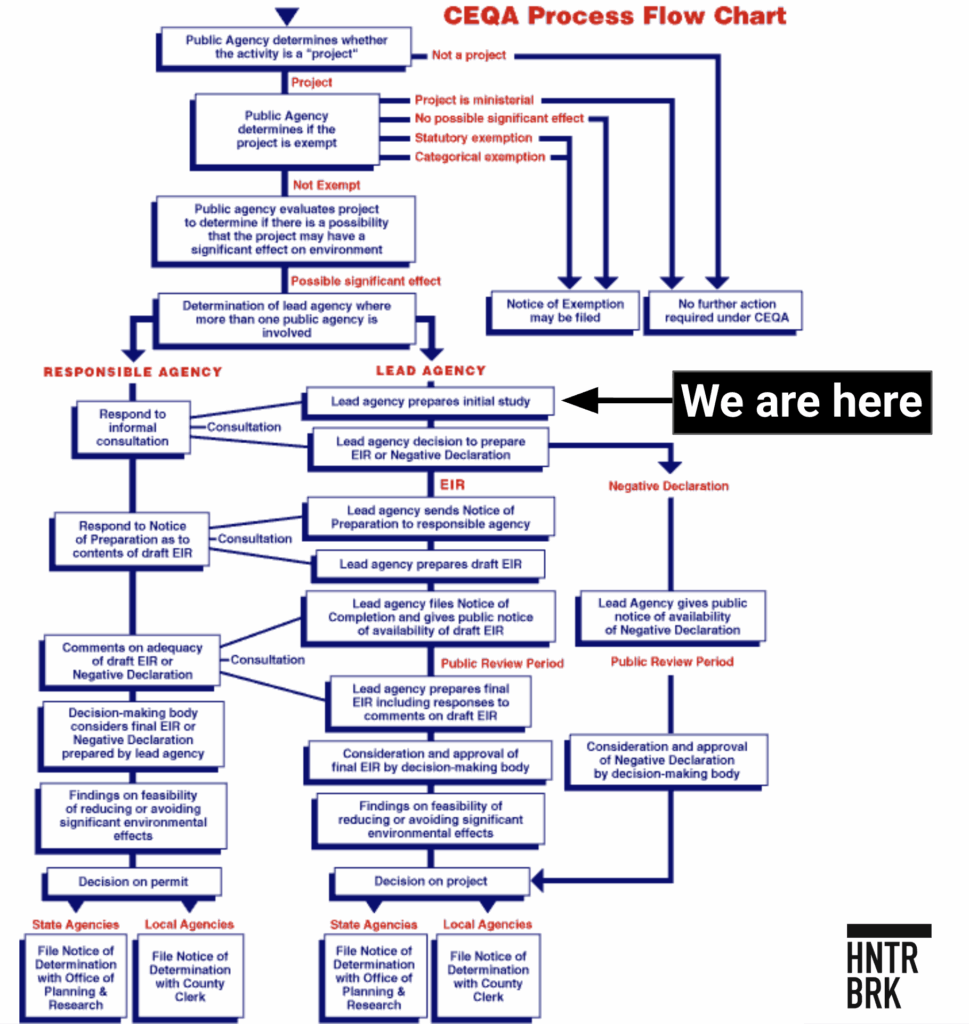

- A state parks easement that expired in 2016. The easement cannot be renewed until California State Parks completes environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act, a process with no overall defined timeline. California State Parks informed Sable it would begin an “initial study” on Nov. 13, which appears to be ongoing, the first step in a process that typically takes months at a minimum.

- An expiring federal emergency special permit that PHMSA granted to waive certain corrosion remediation requirements. The emergency special permit runs out on Feb. 21 and can only be renewed through a formal process requiring public notice and an opportunity for a hearing. PHMSA recently announced a policy not to enforce special permit requirements under certain circumstances, indicating PHMSA likely won’t hold Sable accountable if it operates with an expired permit during the period of renewal. But the legality of PHMSA’s policy may be challenged in court, as was PHMSA’s issuance of the emergency special permit in the first place, in a case before the Ninth Circuit. Briefing is scheduled to be completed in March. But even if Sable is successful in the Ninth Circuit, experts say it won’t impact the ongoing state and local disputes between Sable and various California regulators. The Ninth Circuit litigation concerns only whether PHMSA followed proper process in issuing its permits. It has no bearing on the lawfulness of actions by state regulators.

- A denied county permit after Santa Barbara County’s Board of Supervisors found Sable has “a record of non-compliant or unsafe operations systemic in nature.” On the leaked call, Flores suggested a workaround: operating under Exxon’s permits on Exxon’s behalf. But this approach carries its own risk: Sable likely couldn’t push forward with a rogue restart while relying on Exxon’s permits without Exxon’s (at least tacit) approval. Experts say Exxon is unlikely to approve in the face of two preliminary injunctions and a consent decree that could expose the oil giant to billions in potential liabilities. “They’re too big of a company to do something that stupid,” one former Department of Interior executive said.

- A federal Coastal Zone Management Act review that doesn’t appear to have begun, after the CCC sent a Dec. 23 letter to PHMSA. In the letter, whose substance was disclosed in a Dec. 31 update on a California government website, the CCC asserts that it never received required notice of Sable’s applications and has not waived its right to review the federal agency’s actions. CZMA review can last over six months.

Also, perhaps most challenging for Sable, the CCC can now enforce new state law SB 237, which California implemented on Jan. 1.

The bill has a section designed to stifle Sable, requiring any oil project that has been idled, inactive, or out of service for five years or more to obtain a new coastal development permit — a process that can take years. It may take even longer for a company that has compared the CCC to eco-Nazis and owes the commission $18 million in unpaid fines.

“I’d say it’s unlikely that the commission is going to grant the permit, and then if it denies the permit, then Sable can sue them and say you’ve wrongfully denied our permit, but that’s a process,” said Sivas, the Stanford professor. “Having litigated those coastal development permits, those take a few years to litigate.”

Sable is already suing in court to block the application of SB 237. The company claims the project has been “active” since resuming oil production offshore in May 2025. But petroleum has not flowed through the pipeline since the 2015 spill.

That May activity has also been dismissed by the State of California in a letter obtained by Hunterbrook.

“These activities do not constitute a resumption of commercial production or a full restart of the [Santa Ynez Unit]. Characterizing testing activities as a restart of operations is not only misleading but also highly inappropriate — particularly given that Sable has not obtained the necessary regulatory approvals to fully resume operations,” wrote the State Lands Commission in a May 23 letter.

In fact, the Senate Rules Committee digest for SB 237 specifically cited Sable, as the company pointed out in a recent lawsuit seeking a declaration that the statute doesn’t require it to secure a new coastal development permit from the CCC.

“I think they’d have a hard time making the case that the pipeline was active,” said Elmer Danenberger, a former chief of offshore regulatory programs at the federal Department of the Interior. “They did some well testing, and flowed a little oil to shore, probably in storage there. I don’t think any oil was ever sent into the pipeline that would transmit it.” For that reason, Danenberger claims, Sable is facing an uphill battle.

But more than any particular California regulation, Sable seems to have been stifled by its own actions — which have led to criminal charges.

As Assemblymember Gregg Hart from Santa Barbara told Hunterbrook about Sable’s proclaimed restart: “Sable’s announcement last May shows that the company will go as far as misleading the public and regulatory agencies about their operations to make their shareholders happy. It is reminder for us all that we can’t trust Sable to do the right thing and stay true to their word.” (Hart authored key text incorporated into SB 237).

Sable did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment.

In court, Sable’s lawyer said “there is no doubt now that this is a federally regulated pipeline system. That is not in question.” The company also claimed, in the event Judge Geck lifts her injunction, “we can go forward with our restart plan.”

The Legal Maze

Sable faces an overlapping web of court injunctions, regulatory requirements, and statutory mandates.

On the leaked investor call from early in 2025, Flores breezed through the regulatory landscape with characteristic confidence. “We got them on the run,” he said of environmental opponents.

What has happened since tells a different story.

Nine months after that call, Sable — which originally promised an early 2024 launch — is still not online.

And since going public via SPAC, Sable has diluted shareholders by about 60%, issuing tens of millions of new shares across multiple offerings to stay afloat.

At the close of Sable’s merger with Flame Acquisition Corp. on Feb. 14, 2024, the company had approximately 60.2 million shares outstanding. As of Jan. 2026, the company has approximately 145 million shares outstanding. An investor who owned one share at the merger now owns the same share of a company with 2.4 times as many shares — meaning their percentage ownership has declined by about 58%. Major equity raises include a $295 million public offering in May and a $250 million private placement in November at $5.50 per share.

“My guess is that they are not going to be successful in actually getting this going,” said Sivas.

Here are the obstacles in Sable’s path:

Court Injunction #1: Center for Biological Diversity v. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection

In Center for Biological Diversity v. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, Judge Donna Geck enjoined Sable from restarting the Las Flores pipeline “until 10 court days following the filing and service of notice by [Sable] that Sable has received all necessary approvals and permits for restarting the Las Flores Pipelines and that Sable intends to commence such restart.”

The injunction is unambiguous: Sable cannot restart until it has necessary approvals from OSFM, notifies the court, and waits 10 additional days, during which other parties can challenge Sable’s assertion.

Sable has moved for reconsideration, arguing the case is now moot because the federal PHMSA has taken over regulatory authority from California’s OSFM. The hearing on that motion is set for Feb. 27.

The injunction remains in force until then at the earliest. In court filings, Sable has conceded it cannot restart while this injunction is in place.

In fact, in its motion for reconsideration and at a hearing considering whether to expedite review of that motion, Sable’s lawyers seemingly acknowledged they could not start the 10-day countdown to restart without approvals from OSFM — not PHMSA. Having made that concession, Sable now presumably has no legal basis to claim PHMSA approval satisfies the injunction’s requirements.

So Sable’s only way to escape the injunction is seemingly to get the court to reconsider its original order.

But winning reconsideration is far from guaranteed. Three major problems stand in Sable’s way:

The Consent Decree

When the Las Flores pipeline ruptured in 2015, spilling over 120,000 gallons of crude oil onto the Santa Barbara coast, it triggered years of litigation. Plains All American Pipeline, the operator at the time, was convicted on nine criminal counts and paid millions in penalties. But the legal fallout didn’t end there.

In 2020, the federal government and California reached a settlement with Plains — formalized in a consent decree filed in federal court. A consent decree is essentially a court-supervised agreement: The parties negotiate terms to resolve a dispute, and a federal judge enters those terms as a binding court order. Unlike a private contract, a consent decree is backed as a court order, which can lead to civil or even criminal contempt charges if a party violates it.

Violating a consent decree means violating a court order.

The consent decree in U.S. v. Plains All American Pipeline, L.P. and Plains Pipeline, L.P., No. 2:20-cv-02415, a case in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, governs how and when the pipeline can return to service.

It explicitly states that restart shall not happen until OSFM — not PHMSA — approves a restart plan.

The specific language:

“All outstanding corrective actions in PHMSA’s closed Corrective Action Order (CAO), CPF No. 5-2015-5011H, as amended, are hereby merged into this Consent Decree, as outlined below, and subject to the sole regulatory oversight of the OSFM… If Plains seeks to restart Line 901, Plains shall develop and submit, at least 60 days in advance of a scheduled restart, a written Restart Plan for Line 901 to the OSFM for review and approval. Once approved by the OSFM, the Restart Plan shall be incorporated by reference into this Consent Decree … If Plains seeks to restart the Gaviota-to-Pentland segment of Line 903, Plains shall develop and submit, at least 60 days in advance of a scheduled restart, a written Restart Plan for the Gaviota-to-Pentland segment of Line 903 to the OSFM for review and approval. Once approved by the OSFM, the Restart Plan shall be incorporated by reference into this Consent Decree.”

When Sable acquired the pipeline from Exxon in 2024, it stepped into Plains’ shoes. The consent decree didn’t disappear with the change in ownership. Sable’s predecessor is a party, making Sable bound by its terms.

“You can’t just violate a consent decree. You have to go back to the court and get permission to somehow get out of it or undo it,” said Sivas. “That’s another fight.”

The other parties to the decree include the United States and California representing multiple agencies: the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, California State Parks, the State Lands Commission, and OSFM itself. The Regents of the University of California are also parties.

Any of these parties can enforce the decree. The California Attorney General, representing the state agencies, can seek a court order at any time holding Sable to the requirement that OSFM — not PHMSA — must approve restart.

Environmental groups have already cited this requirement in their filings in the case before Judge Geck.

“While PHMSA may issue permits related to pipeline safety, the consent decree makes clear that authorization to restart Line 901 rests with California’s Office of the State Fire Marshal,” said Assemblymember Hart. “I have full confidence in Attorney General Rob Bonta and his office to evaluate the facts, uphold the consent decree, and take appropriate action if necessary.”

The California Attorney General’s office, which sided against Sable’s accelerated timeline for its reconsideration motion before Judge Geck, has said it is actively considering how best to defend OSFM’s jurisdiction over the pipeline.

For her part, Judge Geck may conclude that regardless of PHMSA’s assertions, OSFM approval remains required under the consent decree — at least until or unless the consent decree is updated — and decline to lift the injunction.

In the meantime, PHMSA and Sable have no authority to unilaterally substitute federal for state oversight in the terms of the consent decree. Nothing in the agreement provides for such a substitution.

The decree says what it says, and it has the force of a federal court order. As the Ninth Circuit has explained, “Although a party may ask the district court [which entered a consent decree] to issue an order clarifying, enforcing, or modifying a decree and suggest a favored interpretation, a party — whether a private or public entity — cannot dictate the meaning of the decree to the court or relieve itself of its obligations under the decree without the district court’s approval.”

In other words, to escape the decree’s OSFM requirement, Sable or the United States would need to go back to the federal court that entered it — the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California — and seek modification under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b). This is the legal mechanism for asking a court to change a prior judgment — but it’s designed to be difficult, because courts want their orders to be final. If California disputes a request for modification, the parties will have to first go through informal and formal dispute resolution mechanisms specified in the agreement before the court reviews the request.

Rule 60(b) has six sub-provisions under which a party can seek to modify a consent decree — only one really potentially applies here. Sable could conceivably seek relief under Rule 60(b)(6), which allows a court to modify a judgment for any other reason that justifies relief. But that’s a catchall term requiring a showing of “extraordinary circumstances.” It’s extremely difficult to satisfy — and the Supreme Court has held it can only be invoked for reasons not covered by the other prongs of Rule 60(b). So it’s almost never successfully invoked in practice. Under Rule 60(b)(5), relief requires a showing that “applying [the judgment] prospectively is no longer equitable.” The Supreme Court has interpreted this to mean the moving party must demonstrate “a significant change in circumstances.”

Here’s the problem for Sable: There has been no change in the underlying law or facts.

The only argument Sable and PHMSA can muster is that PHMSA now considers the pipeline “interstate.” That doesn’t create a change in law. The Ninth Circuit has “reject[ed] the notion that the executive branch of the government can unilaterally create the change in law that it then offers as the reason it should be excused from compliance with a consent decree.”

So PHMSA and Sable must demonstrate there’s been a change in factual circumstances warranting Rule 60(b)(5) relief — after the decree was signed. They must also show that the change wasn’t anticipated when the decree was signed. And they don’t seem to have offered evidence that anything material has changed about the pipeline since the consent decree was signed in 2020. It appears to be the same pipeline constructed to transport oil from the same place. So the same facts that underlie PHMSA’s new “interstate” determination are the ones that were available to the parties when the consent decree was signed in 2020.

Even if PHMSA and Sable could make a showing that something about the pipeline has changed, they’d still have to convince the court that compliance with the OSFM approval requirement is now “more onerous, unworkable, or detrimental to the public interest.”

A unilateral relabeling, by one of the parties to the decree, when the underlying facts have not changed, does not constitute the kind of changed circumstances courts generally require for Rule 60(b)(5).

The Missing Permits Problem

Environmental groups have raised that Sable cannot satisfy the injunction’s requirement of “all necessary approvals” because it lacks:

- A new coastal development permit, now required under SB 237 (more on this later).

- An easement from California State Parks for pipeline maintenance in Gaviota State Park (the previous 30-year easement expired in 2016).

- The transfer of Final Development Permits from Exxon, which Santa Barbara County denied in December.

Under the literal terms of the injunction, Sable cannot restart until it has “all necessary approvals.” These are conceivably necessary approvals. Judge Geck may conclude the injunction remains in force regardless of PHMSA’s position — and regardless of whether OSFM maintains authority over the project.

The Interstate vs. Intrastate Problem

Leaving aside the consent decree, whether PHMSA or OSFM regulates the Las Flores pipeline depends on if the pipeline is considered “interstate” rather than “intrastate.” Under 49 U.S.C. § 60105(a), as a default matter, state authorities — not federal regulators — have jurisdiction over safety standards for intrastate pipelines.

PHMSA claims the pipeline is interstate because it originates on the Outer Continental Shelf. But as the California Coastal Commission explained in a letter to PHMSA, the pipeline may actually originate at the Las Flores Canyon facility onshore, not at the offshore platforms. Subsequently, the California Attorney General and environmental groups left open that they, too, might challenge PHMSA’s assertion of jurisdiction based on the pipeline being “interstate.”

If Judge Geck determines the pipeline is intrastate, the motion for reconsideration likely fails — because it follows that, even without the consent decree, OSFM retains regulatory authority under federal law. And regardless of what Judge Geck ultimately decides, this factual dispute may require additional evidentiary proceedings, extending the litigation further.

Court Injunction #2: Sable Offshore Corp. and Pacific Pipeline Co. v. California Coastal Commission

In Sable Offshore Corp. and Pacific Pipeline Co. v. California Coastal Commission, before Judge Anderle of the Superior Court of California, County of Santa Barbara, Sable has been enjoined from engaging in any further “development” in violation of the CCC’s existing cease and desist order on the pipeline.

Under the injunction, the California Coastal Act, and the Santa Barbara County Local Coastal Program, “development” is defined broadly. It includes:

- Excavation

- Removal of major vegetation

- Fill of wetlands

- Grading and widening of roads

- Installation of metal plates over water courses

- Dewatering and discharge of water

- Removal, replacement, and reinforcement of pipeline and pipeline infrastructure

- Placement of sand and cement bags on the seafloor below and adjacent to offshore pipelines

- Other development associated with returning the Las Flores pipelines to service

The CCC’s cease and desist order does not permit new development until Sable:

(a) Secures a new, final, operative coastal development permit specifically covering the work to be performed;

(b) Secures another final, operative, valid form of Coastal Act authorization for the work; or

(c) Secures a final, formal determination that the work is exempt from the Coastal Act’s permitting requirements.

This injunction does not explicitly bar introducing oil into the pipeline. But it makes operating the pipeline nearly impossible. Sable cannot perform any development to maintain the pipeline without facing massive liability exposure. A pipeline cannot be safely operated if you cannot legally maintain it.

Sable has moved for reconsideration, arguing the injunction was only intended to address past repair activities and that compliance interferes with PHMSA’s regulatory requirements. That hearing is set for Feb. 18. It’s not clear this motion is timely. California requires that motions for reconsideration be filed within 10 days of the filing of a notice of entry for an order. Despite Sable claiming otherwise, a notice of entry was filed on June 13. Sable moved for reconsideration on Dec. 12, six months later.

Sable has also appealed the grant of that preliminary injunction with briefing having been completed Jan. 9.

Given SB 237’s new requirements — which explicitly mandate a new coastal development permit for any oil project inactive for five years or more — this motion and appeal may be beside the point. That’s because, regardless of whether Sable checked the boxes of its last coastal development permit, it may need a fresh one.

SB 237: The New Statutory Barrier

California’s SB 237 took effect Jan. 1.

One aspect of the bill impacting Sable amends the Coastal Act to require that “repair, reactivation, and maintenance of an oil and gas facility, including an oil pipeline, that has been idled, inactive, or out of service for five years or more shall be considered a new or expanded development requiring a new coastal development permit consistent with this section.”

The legal weight of SB 237 appears to have caused some confusion among Sable investors, including on social media. Parts of the bill modify California’s Pipeline Safety Act, which focuses on intrastate pipelines, but Section 9 — the section impacting Sable — amends Section 30262 of the Public Resources Code, part of the Coastal Act, which isn’t focused on safety, covers both intrastate and interstate pipelines, and therefore isn’t superseded by PHMSA. (As PHMSA writes on its website: “The PSA [Pipeline Safety Act] does not preempt rules or regulations that are not related to pipeline safety.”)

The statute provides that “development associated with the repair, reactivation, or maintenance of an oil pipeline that has been idled, inactive, or out of service for five years or more requires a new coastal development permit.”

At Judge Geck’s hearing, Sable claimed its pipeline had been active since last May, but admitted it had not yet introduced oil into the pipeline. That ostensibly means the pipeline qualifies as “idled, inactive, or out of service for five years” under the statute — triggering the coastal development permit requirement.

Along these same lines, Sable filed a lawsuit in Sept seeking a declaration that its pipeline is active for purposes of SB 237 because of its ongoing maintenance activities.

“In my view, Sable’s well-testing activities did not constitute a restart of oil production,” said Assemblymember Hart, who helped write the key language in SB 237. “Sable, and any other oil operator looking to restart aging and dangerous oil infrastructure, should be required to get a permit. It’s the responsible thing to do.”

Sable has also argued that the law only applies to pipelines that are idled, inactive, or out of service for five years starting after Jan. 1, 2026 (so the earliest a pipeline could be inactive would be Jan. 1, 2031). Given the broad language of the statute and the fact that the legislature enacted SB 237 with Sable in mind, the company’s legal argument faces a steep climb.

“I think the state is going to take the position that that law absolutely applies,” said Sivas, the Stanford Law professor. “And I say that because that piece of that law was written for this project, basically.”

Now, PHMSA stated in a letter to Sable that the company’s pipeline is considered “active” under its regulations. But whether the pipeline is “active” under federal regulation is a different matter than whether it’s “idled, inactive, or out of service” as a matter of state law. PHMSA only differentiates between “active” – and therefore fully subject to all safety regulations – and “abandoned” status. “Abandoned” means that the pipeline is permanently and irreversibly removed from service. It’s not coextensive with pipelines subject to SB 237’s new requirements.

Pipelines that are “idled, decommissioned, or mothballed” still fall in the “active” category, because they have “potential for reuse at some point in the future.” This is to hold pipeline owners accountable for lines that may no longer be used, but haven’t been properly sealed off and could still contain oil or gas. And it makes importing the federal active/abandoned distinction an ill fit for determining whether Sable’s pipeline is subject to SB 237.

In order to get around SB 237, said Paasha Mahdavi — Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara — Sable “would have had to admit that they’ve been lying to someone, whether it’s their investors, whether it’s the court, whether it’s the county of Santa Barbara, because there’s no ever indication that they said that they’ve transferred oil from the processing facility to the pipeline.”

And Sable’s lawyers are unlikely to have told such a lie under oath.

If the company or its attorneys lied in state court proceedings, they may have opened themselves up to sanctions or even contempt or perjury charges, depending on the context. The same goes for the Ninth Circuit proceedings — sanctions as well as contempt and perjury charges are all possible in that scenario. Sable’s attorneys would have committed an ethical violation subject to discipline if they knowingly lied to a tribunal.

Assuming SB 237 applies, if Sable restarts — or threatens to restart — without a coastal development permit, the CCC can:

- Send notice of the violation.

- Give Sable time to “respond in a satisfactory manner” (the CCC has previously given Sable as little as one day).

- Issue an executive director cease and desist order, effective for up to 90 days.

- Hold a public hearing for a permanent cease and desist order and administrative penalties.

- Issue a permanent cease and desist order and administrative penalties.

- Seek court orders for injunctive relief and civil monetary penalties for violating the Coastal Act.

Alternatively, the Commission might simply rely on the existing injunction issued by Judge Anderle, which already bars development activities without Coastal Act authorization.

Either way, SB 237 has fundamentally changed the legal landscape.

Sable will have difficulty claiming its decades-old permits suffice. The law now requires a new permit — and obtaining one through the CCC that Flores compares to “eco-Nazis” may not be a quick process.

The Ninth Circuit Case and “Preemption”

There’s been a lot of buzz from Sable’s supporters about a recent win for the company in the Ninth Circuit, which did not issue a stay against Sable. But it offers little hope for the company’s ultimate prospects.

Claiming to have wrested jurisdiction from OSFM, in December, PHMSA “approved” Sable’s restart plan and granted Sable an emergency special permit waiving certain requirements for evaluation and remediation of corroded pipeline segments.

Environmental groups petitioned the Ninth Circuit for review of the emergency special permit in Environmental Defense Center v. U.S. Department of Transportation, No. 25-8059. They argue PHMSA failed to meet the statutory requirements for an emergency special permit (which requires finding that the permit serves the public interest, is not inconsistent with pipeline safety, and addresses an emergency involving pipeline transportation). Instead, the groups argued, PHMSA had to issue a regular special permit following notice and comment procedures, and was required to conduct environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act. PHMSA failed to do both.

On the last day of 2025, the court denied a motion to stay PHMSA’s approval of Sable’s restart plan and the grant of an emergency special permit. That was neither a final judgment nor a ruling on the merits. Specifically, the court found environmental groups hadn’t made the necessary showing for a stay — which requires demonstrating not only a likelihood of success on the merits but also irreparable harm absent a stay, a balance of equities in their favor, and that the public interest supports a stay.

The court offered no reasoning for its decision, which could rest on the environmental groups having failed to meet any one of these criteria. So, for example, the court could have concluded the petitioners didn’t demonstrate they would suffer irreparable harm absent a stay because they didn’t show the pipeline would operate without one. (The pipeline does remain idled, despite the stay being denied).

But there’s also reason to doubt the Ninth Circuit will ever rule on the case’s merits.

The Ninth Circuit has scheduled briefing in the case to conclude in March, meaning it won’t rule before then at the earliest. But emergency special permits are only valid for 60 days. So Sable’s permit, which runs out on Feb. 21, will expire before the Ninth Circuit has a chance to make a decision. Even though Sable’s emergency special permit is expiring, the company likely has cause for optimism that the federal government won’t enforce pipeline safety regulations against it. PHMSA recently announced a policy to not enforce federal hazard and pipeline safety regulations against unpermitted parties if they (1) demonstrate that compliance would contribute to what the federal government terms “the national energy emergency” on the West Coast, (2) show that deferred compliance will not “unreasonabl[y] risk . . . public safety, property, or the environment” and (3) apply for a special permit promptly (no later than 45 days after determining compliance would contribute to the “emergency”). When granting Sable’s emergency special permit, PHMSA already found waiving safety requirements to be “in the public interest,” “not inconsistent with pipeline safety,” and “necessary to address an actual or impending emergency involving pipeline transportation.” So it’s likely PHMSA won’t take enforcement action against Sable moving forward while its renewal is pending. That may make the case moot. And assuming the case becomes moot, the Ninth Circuit will lose jurisdiction before making a merits-based judgment. That date is also notable because it is before Judge Geck will rule on whether to reconsider her injunction (hearing on Feb. 27). So Sable can’t take advantage of the emergency special permit before it expires.

A new case could emerge if PHMSA renews the emergency special permit. But renewal is not automatic. Under federal law and implementing regulations, renewal of an emergency special permit requires public notice and an opportunity for a hearing.

“I think they’d have to allow at least 30 days for public comment. I think that would be the minimum,” said Danenberger, the former chief of offshore regulatory programs at the Department of the Interior. “Now, they may under their law or under their regulations … try and do it in like one week or two weeks, but then that just opens the door to further legal action and makes a farce out of the whole process.”

A case challenging any renewal won’t be ripe until permit approval occurs — adding more delay. There’s no guarantee the Ninth Circuit will even get a new case; it would have to be brought by a person or group, like the environmentalists, harmed by the renewal of the permit. These organizations might be reluctant to bring another case after the adverse ruling on their stay motion — and given the range of state-level protections seemingly blocking Sable from restarting its project regardless of what PHMSA does.

A Note on Preemption

Sable’s attorney has claimed that the company faces a “constitutional quandary.” The company seems to be arguing that the state court injunctions must be lifted now that there is a federal case ongoing. “We cannot have a federal court saying we are permitted to restart the pipeline and a state court order saying the opposite.”

This, as a matter of black letter law, is incorrect.

Preemption is a doctrine about when a court will find federal and state law conflict such that federal law supersedes state law. It goes to the merits of a dispute before a court, not to which court can hear the case.

Preemption does not give federal courts the power to disregard or stay the orders of state courts. Under the Anti-Injunction Act, federal courts generally cannot stay state court proceedings except in narrow circumstances that don’t apply here (“expressly authorized by Act of Congress, or where necessary in aid of its jurisdiction, or to protect or effectuate its judgments”). Neither Sable nor PHMSA has sought a stay of any state court proceedings from the Ninth Circuit, almost certainly because the case before it doesn’t afford an opportunity for such a drastic remedy.

State and federal courts routinely hear overlapping cases involving the same parties and related legal issues. This is not a constitutional crisis. It’s normal. As the California Attorney General’s office said in Judge Geck’s court: “The fact that state courts and federal courts deal with overlapping issues happens all the time.”

At the outset of litigation, claims arising under federal law can be removed from state court to federal court within 30 days of the complaint. But the proceedings before Judges Geck and Anderle are (1) not “arising under” federal law in the technical sense required for removal and (2) well past 30 days from the complaints.

If state courts get federal law questions wrong, the remedy is appeal through the state court system, potentially up to the U.S. Supreme Court. As the Supreme Court itself has repeatedly explained, because of the “fundamental constitutional independence of the States, Congress adopted a general policy under which state proceedings ‘should normally be allowed to continue unimpaired by intervention of the lower federal courts, with relief from error, if any, through the state appellate courts and ultimately th[e Supreme] Court.’” The lower federal courts cannot simply intervene in state proceedings.

As a matter of California law, if another court, like the Ninth Circuit, decides an issue before a state court rules on it, and that issue (1) is identical to the one before the state court, (2) was actually litigated in the prior proceeding, and (3) was necessarily decided in that prior proceeding for a final judgment on the merits, the state court may be bound to follow that decision.

The prior proceeding must also have been litigated by the party whom the decided issue is being used against in state court or at least a party who is in “privity” with that disadvantaged party. Different parties in different suits can only be in “privity” if they have interests so similar to each other that the party to the first proceeding acted as the second party’s “virtual representative” there. Even if these showings are met, public policies like “preservation of the integrity of the judicial system,” “promotion of judicial economy,” and “protection of litigants from harassment by vexatious litigation” must favor holding a party to the resolution on a previously decided issue. This doctrine is referred to as collateral estoppel or issue preclusion. This doctrine also works both ways. If a state court rules on an issue before a federal court (like the Ninth Circuit does), the federal court too is generally bound by collateral estoppel.

There are several reasons why it’s unlikely any issues in the Ninth Circuit case will have a preclusive effect in the state court proceedings. First, per above, there’s been no final judgment on the merits. The Ninth Circuit’s denial of a stay of the emergency special permit was neither a final judgment nor a ruling on the merits. And there’s a strong reason to believe that the Ninth Circuit will never rule on the merits. That’s because the Ninth Circuit won’t rule until after the emergency special permit expires. So the case will seemingly be moot by then.

Second, even if the Ninth Circuit were to rule on the merits, the issues that are being litigated are not the ones that are going to influence the state court judgments. For example, key issues in Judge Geck’s courtroom are whether the Las Flores pipeline is properly classified as “interstate” or “intrastate” under federal law and whether Sable still needs approval from OSFM. These are not issues raised in the Ninth Circuit case, which is about whether PHMSA followed proper process in issuing emergency special permits, not whether it had jurisdiction in the first place over OSFM.

Finally, even if the Ninth Circuit were to decide issues relevant to Judge Geck and Judge Anderle’s cases, the decision couldn’t be used against parties not party to the Ninth Circuit suit. So it couldn’t be used against the CCC in Judge Anderle’s case or the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection in Judge Geck’s case. Neither of these agencies are in “privity” with the environmental groups, PHMSA, and Sable, who are parties to the Ninth Circuit case. They have distinct interests as state organs.

Any preemption issues will be ruled on by state court judges in their respective state court cases.

“I think that Sable might raise the argument that somehow the local and state permitting requirements are preempted by the Pipeline Act, but I don’t think that’s going to be successful,” said Sivas.

The Missing State Parks Easement

Sable needs an easement from California State Parks for a four-mile section of pipeline that runs through Gaviota State Park. The previous 30-year easement expired in 2016.

On the leaked investor call, Flores described the easement situation with characteristic optimism. “We are very close to getting an agreement there,” he said, nine months ago.

But on Nov. 13, State Parks notified Sable that it would need to complete an environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act before any easement could be granted. It would start the process by preparing an “initial study.”

CEQA review has complicated timelines. It can take months or years depending on the complexity of the project and whether environmental groups challenge the review. Given the history of litigation surrounding Sable’s project, expect a challenge to the agency’s determination however it comes out.

On the investor call, Flores described a temporarily workaround of the easement: “We worked around this because of the two-week delay, we actually were able to pump water into our pipeline and do a volumetric hydro test around on the pipeline and we got water all the way around past the parks.”

But hydrotesting the pipeline is different from operating it commercially. Sable may have completed testing, but it cannot operate the pipeline through Gaviota State Park without an easement. And it cannot get an easement without completing CEQA review.

The Denied County Permits

On Dec. 16, Santa Barbara County’s Board of Supervisors voted to deny the transfer of Final Development Plan Permits from Exxon to Sable.

The Board’s finding was damning: “Sable reflects a record of non-compliant or unsafe operations systemic in nature for the Facilities being considered for operatorship, and therefore does not have the skills, training, and resources necessary to operate the permitted Facilities in compliance with the applicable permits and all applicable county codes.”

On the leaked call, Flores suggested a workaround: “We have a deal with Exxon to do an operating agreement with Exxon, operate on their behalf if we don’t get [the permits] preproduction.”

But this arrangement — Sable using Exxon’s permits on Exxon’s behalf — raises its own legal issues. And it doesn’t solve the fundamental problem: The County found Sable lacks the capability to operate safely.

Flores told investors he expected the County to come around. “We put a lot of pressure this week on them,” he said. “Hopefully we’ll get a resolution.”

The resolution came: The Board said no.

Now, Sable may still try to operate under Exxon’s permits — but experts say the oil and gas giant is unlikely to go along with a restart in defiance of two injunctions and without required coastal development permits in place.

“I don’t think Exxon defies the courts, and they’re too big of a company to do something that stupid,” said Danenberger.

Exxon did not respond to a request for comment.

The Coastal Zone Management Act

The federal Coastal Zone Management Act gives state coastal management agencies — in California, that’s the CCC — the right to review federal actions affecting coastal resources.

In a Dec. 23 letter to PHMSA (copying Sable), the CCC preserved its right to invoke this process. The CCC stated that both PHMSA’s approval of the restart plan and any special permit applications are “unlisted federal license or permit activities” subject to CZMA review.

Here’s how the CZMA process works, and why it could create a delay:

Step 1: Notice

Under federal regulation, the CCC has 30 days from receipt of notice of Sable’s applications to notify PHMSA, Sable, and the director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management (formerly the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management) that it is exercising its right to CZMA review. If the CCC doesn’t notify within 30 days of proper notice, it waives its right.

The CCC claims in its letter that it had not received proper notice — and, therefore, that the 30-day clock hadn’t started. Notice must be written notice sent directly to the state agency or published in an official federal notification document or through a state clearinghouse. There’s no indication PHMSA provided such notice.

Step 2: Director Review

Once the commission gives notice it’s requesting review, PHMSA and Sable have 15 days to comment to the Office for Coastal Management director. And the director has 30 days to approve or disapprove the commission’s request based on whether the activity’s coastal effects are “reasonably foreseeable.” The director can extend this deadline.

If the director disapproves the request, the CCC could sue, arguing the director exceeded their discretion. If the CCC loses or doesn’t sue, the CZMA process ends and the permits are approved.

Step 3: Consistency Certification

If the director approves the CCC’s review request (or if Sable voluntarily agrees to undergo certification, which it is unlikely to do), Sable must amend its applications with a “consistency certification” and provide the CCC with all necessary data and information.

Step 4: Commission Review

The CCC has at least the later of six months from its original receipt of notice or three months from the submission of the consistency certification to object. If it doesn’t object within that window, federal regulations conclusively presume the commission concurs with PHMSA’s approvals.

Step 5: Secretary of Commerce Appeal

If the CCC objects, Sable can appeal to the Secretary of Commerce within 30 days. The Secretary can override the CCC’s objection and give PHMSA the go-ahead to approve Sable’s permit(s) only if they find that the activity is “consistent with the objectives or purposes of the [Coastal Zone Management] Act” and is “necessary in the interest of national security.” Even if Sable is successful, the appeals process can take a couple months to nearly a year.

If the Secretary overrides, the permits are issued (though the CCC could sue arguing the Secretary exceeded his discretion). If the Secretary doesn’t override, the permits aren’t issued.

The Timing Problem

PHMSA purported to approve Sable’s restart plan without completing CZMA review.

The CCC’s Dec. 23 letter makes clear the CCC has not waived its CZMA rights. If PHMSA refuses to engage with the CZMA process, the commission could sue to vacate the approvals as procedurally defective. That would add months of uncertainty to the pipeline project.

And in the best case for CCC, where PHMSA and the Office for Coastal Management director cooperate with the commission, the process can still take up to six months, while CCC reviews Sable’s operations. If the commission objects and Sable appeals to the Secretary of Commerce, that would add many months.

The CCC’s letter also reserves the right to review Sable’s activities under a different CZMA pathway — for outer continental shelf (OCS) exploration, development, and production activities.

This pathway involves other review requirements, including submission of OCS plans to the Department of the Interior with consistency certifications, and a six-month commission review period with various notification requirements. Environmental groups have sued the Secretary of the Department of the Interior for failing to require Sable to update its development and production plans in accordance with the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act. The next hearing in that case, on a motion for summary judgment, is in May 2026. They also sued the Department of the Interior for extending Exxon’s offshore oil and gas leases, on which Sable relies.

Additionally, the CCC writes that it is reviewing whether PHMSA’s determination that the pipeline is “interstate” is itself a federal agency action with reasonably foreseeable coastal effects subject to consistency review. If so, that opens yet another procedural track for CCC to delay pipeline approval.

The CCC declined to comment.

The Financial Reality

As of Sept. 30, Sable reported just $41.6 million of cash and cash equivalents.

Less than two months later, presumably with even less cash in the bank, Sable found a lifeline, issuing $250 million in equity at $5.50 per share.

But the problem is the burn.

Based on Sable’s cash flow statements, it spent $253.6 million in operating cash over the first nine months of 2025 and $323.1 million on capital expenditure over the same period.

That’s more than double what the company projected in a Nov. 2024 investor presentation, where Sable said it expected capex to be somewhere between $110 and $130 million over the entire year. (What makes this especially notable: At the time Sable made these projections, the company was claiming it would restart early in the year. Which is to say, Sable ended up spending more than three times as much as projected, without even needing to incur the expenses required to operate the project.)

And Sable currently has no revenue. The Santa Ynez Unit is its only asset. “It’s not a company. It’s just an idea at this point,” said Clark Williams-Derry, an energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

In the third quarter of 2025, the company’s burn was around $80 million per month. If Sable is still burning cash at anything like that third-quarter pace, its raise only bought the company roughly three months of runway. Counting from the Nov. 12 close date, that model implies Sable has less than $100 million in cash as of mid-January, and would hit the wall in roughly mid‑to‑late February — right around (or even before) the next major court dates.

Sable is also required to maintain a cash balance of $25 million under its loan agreement with Exxon, meaning the date by which Sable would need to raise cash could come even sooner.

“There’s a reason that nobody wanted to buy the Santa Ynez Unit. Exxon loaned Sable the money to buy it, because nobody else wanted to do that,” said Williams-Derry. “And so adding additional cost to a product that was already unwanted, unloved, financially stressed? I think that’s a possibility, but in terms of a long-term financial plan, you’re basically throwing good money after bad.”

Absent a dilutive raise, legal obstacles outlined above suggest restart is essentially impossible before Sable runs out of money. The Geck hearing isn’t until Feb. 27. Even if Sable prevails, it still faces the Anderle injunction, the CZMA process, the permit issue, the CEQA review for the State Parks easement, and the consent decree’s OSFM requirement.

And even if Sable manages a restart, its project may not be as profitable as it once thought. In its Nov. 2024 investor presentation, the company calculated the estimated cash flows from its oil resources based on a price of $83 per oil barrel. Oil is now around $60 per barrel.

Meanwhile, Sable’s debt is enormous.

As of quarter-end, Sable disclosed $896.6 million of outstanding debt. And its balance sheet showed $53.3 million in accounts payable, or $163.7 million if you include accrued liabilities.

The cost of its debt is also rising: After the October amendment became effective, Sable’s term loan with Exxon accrues at 15% per year (compounded annually). Sable can elect to “pay” interest by adding it to principal. On roughly $897 million of debt, that’s approximately $135 million per year — about $11 million per month — piling onto the balance. (This is in addition to the $4 million per month Sable owes Exxon due to its failed permit transfer.)

“I don’t think Sable survives without more money from Exxon or Exxon further deferring their obligations and adding to them,” said Danenberger.

Any new capital Sable raises will likely come with unfavorable conditions.

“The cumulative risk profile is of a company that is waving every red flag,” said Williams-Derry. “You could wave it to the capital markets, and that doesn’t necessarily mean that they won’t get money, but it means that they’ll pay for it.”

And there’s still the cliff-edge in the underlying Exxon deal structure.

The Exxon purchase agreement gives Exxon a free reassignment option: If Sable fails to “restart production” by Mar. 31, Exxon can demand reassignment of the assets within 180 days, “without reimbursement of any Purchaser costs or expenditures.”

In other words: Exxon can just take back the asset. For free.

And if Sable’s regulatory pathway is really just delayed, not denied — as Sable claims — that may be a more appealing proposition for Exxon than it once was.

Or, perhaps, Exxon will decide to retire the project, recognizing the Sisyphean path to production. (Exxon already took a $2.5 billion write-down as part of exiting offshore operations in California.)

Either way, for now, Sable is doing what it often has: promising investors a restart is imminent.

Maybe this time will be different, and after years of blown timelines, “Big” Jim Flores will finally live out his Daniel Plainview dreams of liquid gold. But so far, at least, the “Teflon” “eco-Nazis” remain ahead.

And the “status quo,” as Flores put it, is that Sable’s pipeline remains a pipe dream.

AUTHORS

Jacob Hutt contributes to Hunterbrook following a clerkship with the Honorable Robin S. Rosenbaum of the US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. He is a licensed attorney barred in the District of Columbia, has interned for the US Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, and completed a summer associateship with Sullivan & Cromwell LLP. He has assisted with drafting amicus briefs before the Supreme Court and coauthored on the evolving legal landscape during the COVID-19 pandemic. He has worked on cases involving constitutional law, statutory interpretation, civil rights, voting rights, criminal prosecutions, health care, employment discrimination, consumer protection, and more. He holds a BA from Yale University in political science and a JD from Yale Law School.

Till Daldrup joined Hunterbrook from The Wall Street Journal, where he focused on open-source investigations and content verification. In 2023, he was part of a team of reporters who won a Gerald Loeb Award for an investigation that revealed how Russia is stealing grain from occupied parts of Ukraine. He has an M.A. in Journalism from New York University and a B.S. in Social Sciences from University of Cologne. He’s also an alum of the Cologne School of Journalism (Kölner Journalistenschule).

EDITOR

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life.

Graphics

Dan DeLorenzo is a creative director with 25 years reporting news through visuals. Since first joining a newsroom graphics department in 2001, he has built teams at Bloomberg News, Bridgewater Associates, and the United Nations, and published groundbreaking visual journalism at The Wall Street Journal, Associated Press, The New York Times, and Business Insider. A passion for the craft has landed him at the helm of newsroom teams, on the ground in humanitarian emergencies, and at the epicenter of the world’s largest hedge fund. He runs DGFX Studio, a creative agency serving top organizations in media, finance, and civil society with data visualization, cartography, and strategic visual intelligence. He moonlights as a professional sailor working toward a USCG captain’s license and is a certified Pilates instructor.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.