Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. Full disclosures below.

The air in Port Neches, Texas, is thick, even in December. A pungent smell permeates the city — schools, parks, restaurants, hospitals, and grocery stores. The odor is reminiscent of burning plastic mixed with the smell of a gas station pump. Some locals say they stopped noticing it a long time ago.

This region in southeast Texas is known as the Golden Triangle because of the wealth generated by the massive oil boom in the early 1900s. But today, some residents say the economic opportunities the petrochemical industry has offered them and their neighbors have come at a high personal cost.

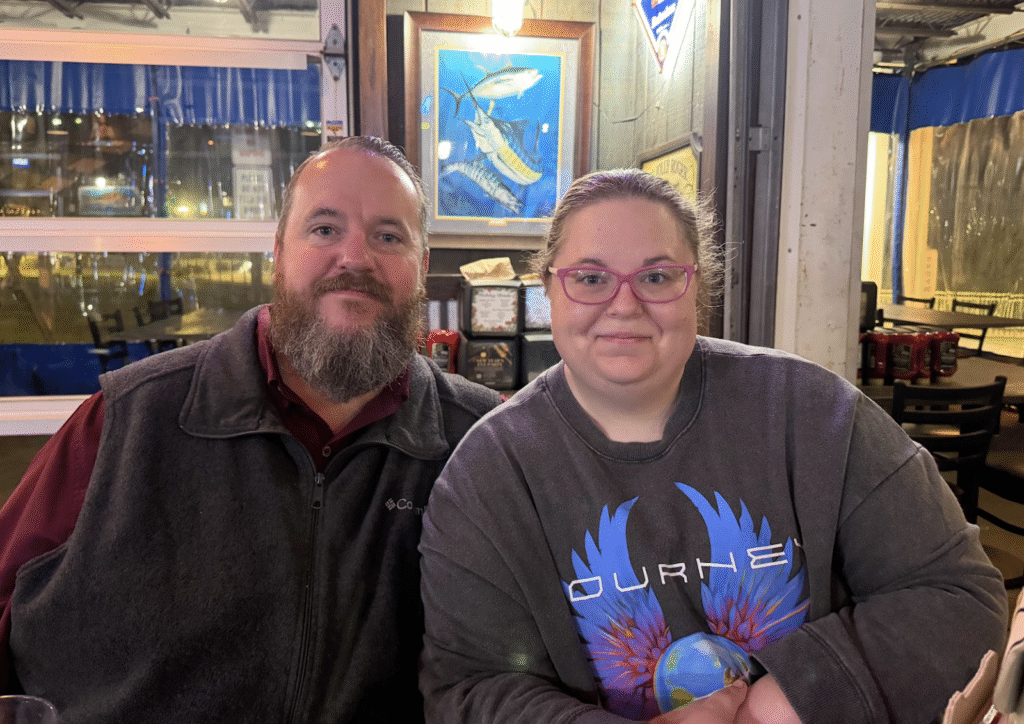

“You live here, you’re gonna get cancer,” a local mother said. She prefers not to be named because of her relationships with people who work in the oil and chemical industries.

Timothy, her son, is an ICU nurse. Both of them grew up in the Golden Triangle. They have another name for the region: cancer alley, reminiscent of the nickname for an 85-mile stretch of petrochemical plants and refineries along the Mississippi River in Louisiana.

He said he has personally treated countless locals with various cancers, including numerous cases of patients with lung cancer who never smoked.

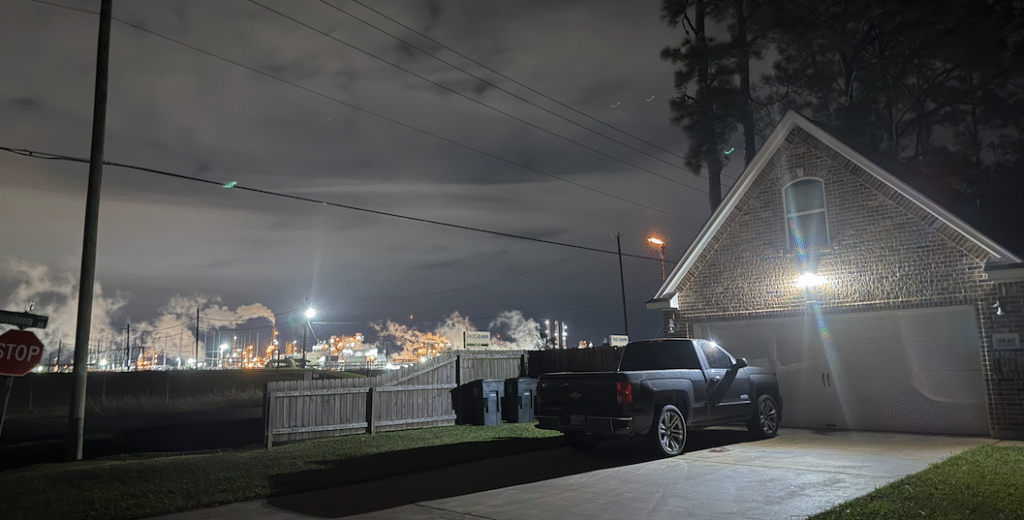

For Timothy and his mother, the flames, the smoke, the never-ending smell of chemicals coming from refineries and petrochemical plants are a fact of life. So are the sirens that go off during the day. And the eerie orange glow in the sky at night, from the lights on machinery at the plants.

Residents feel “helpless to do anything about it,” Timothy’s mother said. And the plants and refineries are the economic lifeblood of the region. “You weigh the risks of living in the area with the good living wages that you get.“

Sign Up

Breaking News & Investigations.

Right to Your Inbox.

No Paywalls.

No Ads.

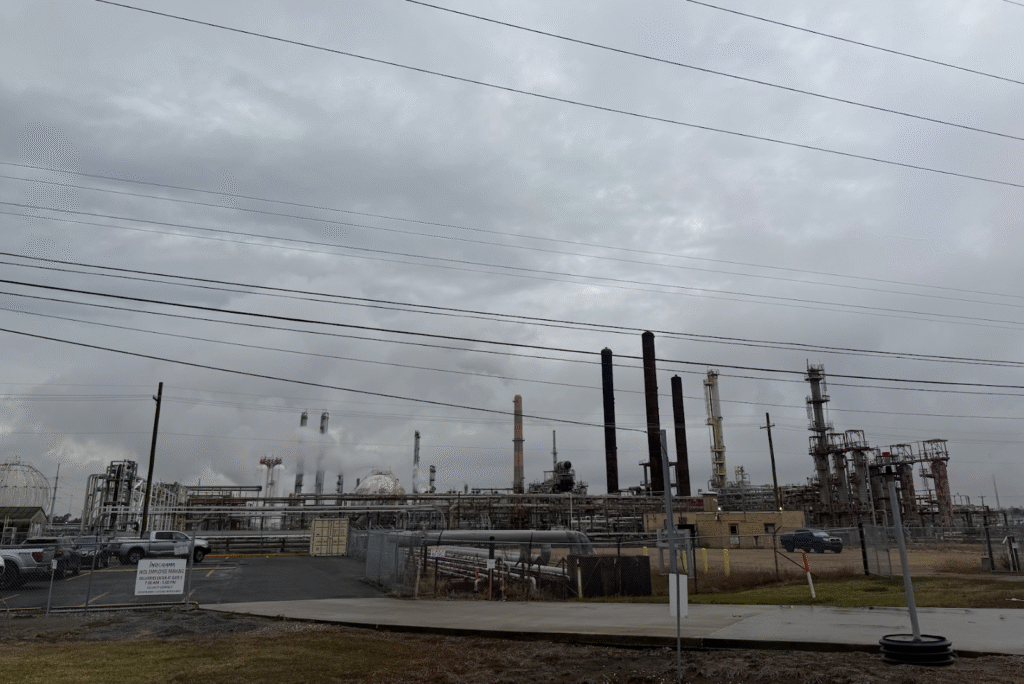

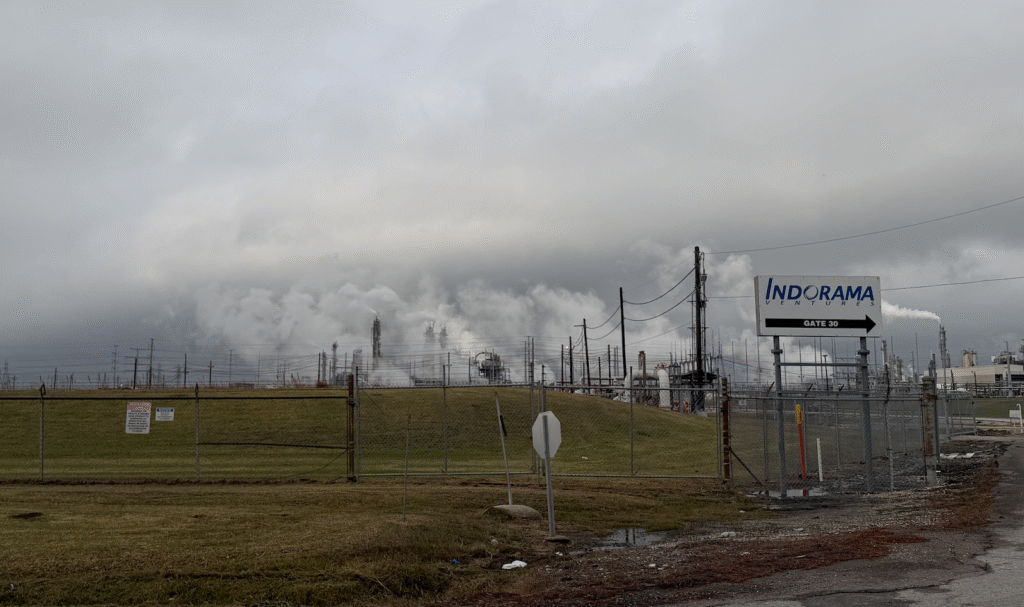

Inside Indorama’s Chemical Footprint in Texas

About 600 people in this area work for Indorama Ventures ($IVL), a $3.8-billion Thai petrochemical company. In 2020, it bought a complex in Port Neches that borders Groves and Nederland. Indorama referred to the plant as a “large flagship site on the US Gulf Coast.”

Documents obtained by Hunterbrook Media through public records requests show that the company has exposed residents of all three cities to high levels of a cancer-causing chemical.

Indorama’s plant produces ethylene oxide (EtO), a colorless, flammable gas used to make antifreeze, detergents, and textiles, and as a sterilizing agent for medical devices. It is also a ruthlessly efficient carcinogen. In 2016, the EPA in a revised toxicity assessment concluded it is 30 times more carcinogenic than previously thought. Ethylene oxide is linked to blood cancers like leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma, as well as breast cancer. In 2024, the EPA issued stricter rules that require commercial medical sterilizers and large chemical plants to reduce their ethylene oxide emissions.

A former Indorama employee who specialized in ethylene oxide at the Port Neches plant emphasized the extreme danger the gas poses. Malfunctions could “wipe out Port Neches,” they told Hunterbrook.

Given the highly hazardous nature of the chemicals it handles, Indorama has publicly stressed its responsibility to the surrounding communities.

“It’s a question of what you have to do right,” Chad Anderson, at that time Indorama’s vice president of manufacturing, told local media in 2021, “and that falls down to being responsible and abiding by our environmental permits, keeping employees and clients happy and maintaining our civil engagement.” That was shortly after the company took over the plant.

Yet, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality records show that Indorama has repeatedly failed to contain the carcinogen. The plant has emitted several thousand pounds of ethylene oxide and other toxic chemicals without TCEQ authorization. The records show a pattern of accidents and leaks at the plant that have exposed thousands of local residents to hazardous air pollutants.

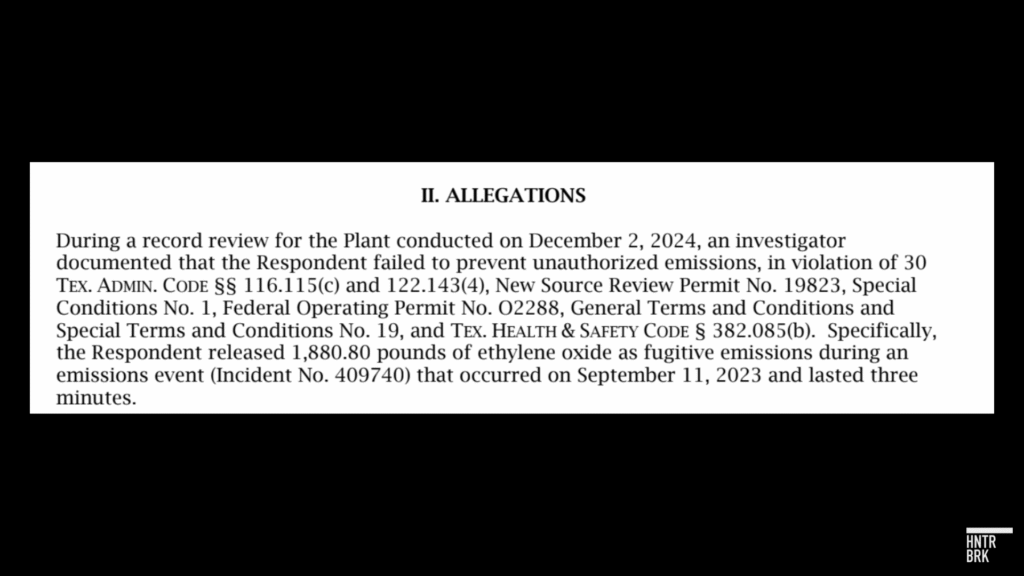

During six record reviews in 2024, the TCEQ found Indorama had exceeded its permitted emission limits several times in 2022 and 2023 and hadn’t notified regulators or the public of large chemical releases at its facility.

In one previously unreported incident, Indorama in September 2023 emitted roughly 1,880 pounds of ethylene oxide during a mere three-minute leak caused by defective tubing.

This brief emission alone would have made Indorama one of the top 20 emitters of ethylene oxide in the United States in 2023, according to the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory database.

For context, in 2023, Sterilization Services of Tennessee, a medical sterilization company, announced it would shut down its plant following months of community advocacy against its EtO emissions. It had released 2,000 pounds of ethylene oxide that year. Indorama released nearly that same amount in 180 seconds.

What’s more, the records show that Indorama did not report three releases to regulators until a TCEQ investigator discovered them during a record review. Two of these leaks were uncovered over a year after the fact. According to Texas regulations, facilities like Indorama’s are required to notify authorities of large emissions events within 24 hours.

Jefferson County — which includes Port Neches, Groves, and Nederland — has the highest breast cancer mortality among women under the age of 50 in Texas, according to the latest available National Cancer Institute data. Long-term ethylene oxide exposure is linked to a higher rate of breast cancer. The county also has the second-highest incidence of lung and bronchus cancers among people under 50 in the state, as well as one of the highest death rates from stomach cancer.

A 2021 ProPublica analysis calculated the cancer risk caused by industrial pollution across the United States based on emissions data and identified the area around Indorama’s facility as a major national hotspot. The estimated cancer risk around the facility is 1 in 53 — meaning that for every 53 residents, 1 is likely to develop cancer solely due to toxic exposure.

Indorama’s plant is not the only polluter in the area. Several nearby refineries and petrochemical facilities are also adding to the toxic cocktail that residents are exposed to daily.

But an ethylene oxide emitter of that size in such close proximity to several communities is rare, according to a Hunterbrook review of large EtO emitters. The only plant that released more ethylene oxide than Indorama’s Port Neches facility in 2023 was Dow Chemical’s ethane cracker in Plaquemine, Louisiana. Indorama’s facility is still listed under its old name “HUNTSMAN PETROCHEMICAL LLC PORT NECHES FACILITY” in the EPA Toxics Release Inventory. But while Dow’s facility is located next to a relatively sparsely populated strip of land, Indorama’s plant is located less than 1,000 feet from Groves Middle School. Port Neches Primary School is less than one and half miles from the facility.

And it’s not just ethylene oxide. Indorama released more than 7,300 pounds of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and 1,500 pounds of nitrogen oxides (NOx) between July 7 and July 10, 2023 — in violation of its permits, according to the TCEQ. An incident report shows this was due to an equipment malfunction.

Volatile organic compounds can cause various health issues, from eye and throat irritation and headaches to liver, kidney, and central nervous system damage. Some can cause cancer. Nitrogen oxides like nitrogen dioxide can aggravate respiratory diseases, particularly asthma, leading to symptoms like coughing, wheezing, or difficulty breathing.

Indorama did not respond to a request for comment.

“It’s very hard on my asthma,” Timothy said of the plant’s emissions. “I’ve been on the bathroom floor vomiting from coughing so hard.”

He and his mother had never heard of these accidental releases and were unaware of the thousands of pounds of carcinogenic ethylene oxide that Indorama emitted in violation of its permits in recent years. “We don’t know that,” Timothy said. “They hide that from us.”

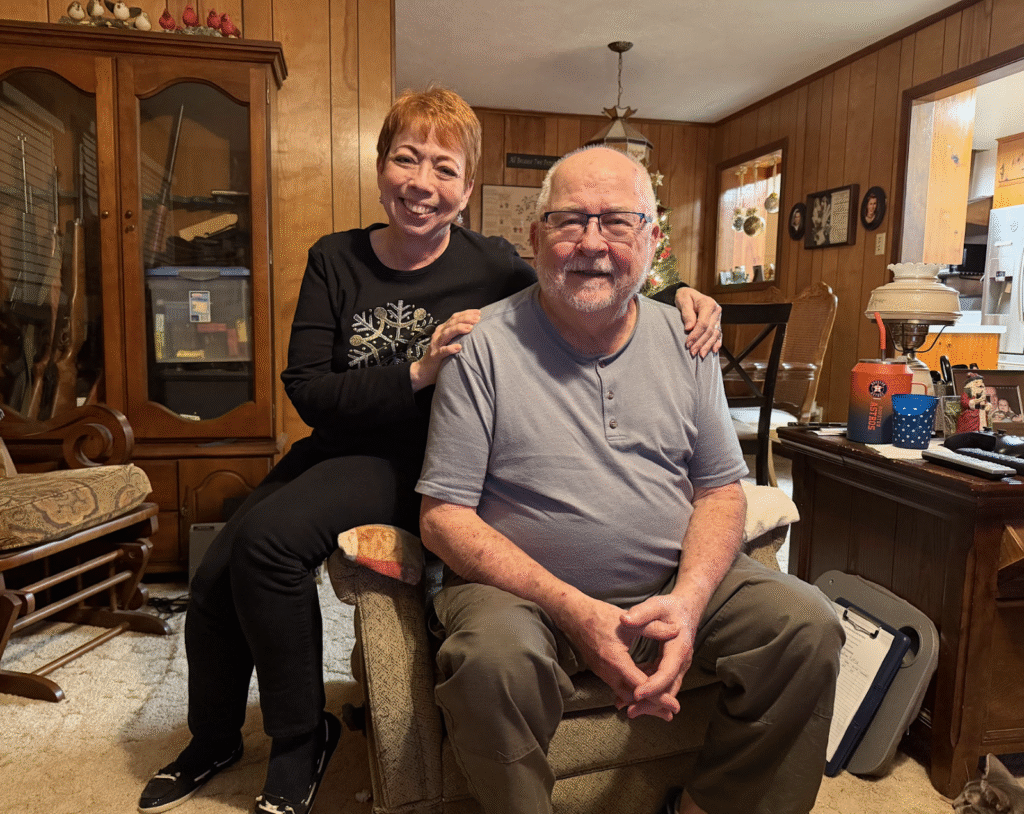

Cindy and Don Colwell said the same — and they live directly across the street from Indorama. “We’ve never heard anything,” Cindy said. They mentioned they had never seen or heard anything about the releases during their time living in Groves — nothing in the news, no phone alerts, and no written notifications.

“It would be nice to know what we are breathing,” Cindy said.

Their wood-paneled living room is filled with photos of their family. Their rescue animals, two dogs and three cats, lay by their feet. The Colwells have gotten used to the flares, they said, and the noises from the plant that sound like airplanes.

But they are also aware of the risk. Several of their loved ones have died from cancer. Cindy listed all of the cancers that had plagued her family and friends: breast cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, liver cancer, mesothelioma, and more.

While the Colwells are deeply concerned about their young grandchildren, for them, the tragedies that come with the oil and chemical industry in southeast Texas are part of the trade-off. “Well, I’m gonna die of something,” Cindy joked. “You can live as healthy as you want, it’s not gonna stop carcinogenic things from tearing into your body.”

But the health data is impossible to ignore. Jefferson County has the highest breast cancer mortality rate among women under 50 in the state. Its mortality rates for heart and long-term lung disease are respectively 38% and 46% above the state average, according to data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

A Hunterbrook analysis using National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration plume models shows that the single three-minute leak in September 2023 dispersed ethylene oxide as far as Louisiana.

The EPA models cancer risks for some air pollutants based on continuous exposure over a 70-year lifespan, so it’s difficult to estimate the increased cancer risk from acute exposure. For ethylene oxide, the agency considers a continuous lifetime exposure above 0.02 micrograms per cubic meter an “unacceptable” cancer risk. After the release at Indorama’s facility, ethylene oxide concentrations peaked at levels over 6,000 times higher than that on one residential block close to the plant.

New EPA rules for chemical plants would have required Indorama to set up fenceline monitoring by July of this year, with an action level for ethylene oxide set at an annual average of 0.2 micrograms per cubic meter. Exceeding this threshold would have triggered a root cause analysis and corrective actions. But Indorama received a presidential exemption for its Port Neches plant in July 2025, which granted the company a two-year extension of compliance deadlines set in the EPA rule.

Ethylene oxide concentrations peaked at more than 600 times the action level after the three-minute release at Indorama’s facility. Almost 5,000 people were exposed to concentrations five times the threshold for at least an hour.

And documents reviewed by ProPublica suggest that ethylene oxide levels around the facility have at least periodically been above the EPA threshold in recent years: When the agency asked Indorama to temporarily set up fenceline monitors in 2023, the ethylene oxide concentration was seven times higher than the action level, according to ProPublica’s investigation.

“Too Big to Fail”

For some residents, the cycle of leaks and lenient fines has bred a deep cynicism.

“Because of their contribution to the economy, they all enjoy the ‘too big to fail’ pass,” said Bill Johnson.

He and his wife Alicia live in Port Neches near the Indorama plant with their teenage daughter. They said the “deafening” sounds from the facility and the pollution are a part of their daily lives. The Johnsons were also unaware of the dangerous emissions from Indorama in recent years.

“If I am responsible for an accident that causes damage to 60,000 homes in the area,” Bill said, giving a figurative estimate, “I’m going to prison for eternity, right? I’m gonna be fiscally liable. But because of their contribution to the economy, they get a pass.”

He worked in the industry for many years. Risk has been a constant in his working life, something he learned to live alongside rather than fear.

“It’s become such a fact of life around here,” Bill said. “I don’t wanna be living across from a refinery for the rest of my life … but there isn’t really an option.”

Moving is more of a fantasy than a plan for him and his family. “It does kinda feel like the big bad wolf is the plant, and in the end it’s them saying, ‘If you don’t like it, you can move’ … but I don’t have millions of dollars. Y’all do,” Bill said.

Alicia agreed. “Who can afford to just pack up and move?”

Like nearly every other local who spoke to Hunterbrook for this story, their lives are intertwined with illness. A friend of theirs who grew up in Port Neches developed cancer and was told by doctors that it was environmental. Bill and Alicia understood the connection but also the futility of confronting it.

To the Johnsons, Indorama is not just a neighbor; it’s a company that defines everything around them. Bill described the plant as “swallowing up the town.”

“This is Port Neches, not Port Indorama,” Bill said.

The penalties the TCEQ proposed for the various violations it identified at Indorama’s plant in Texas add up to almost $75,000, according to the documents Hunterbrook obtained. For a company that recorded $15.4 billion in revenue in 2024, that’s barely a rounding error.

Two of the proposed orders with penalties totaling around $43,000 were adopted by the Commission on January 28. Another, carrying a penalty of about $10,000, was signed by the TCEQ’s executive director earlier that month. One other order is still pending approval.

The Commission is also working on enforcement cases for five other air emissions incidents at Indorama’s facility involving ethylene oxide releases between 2021 and 2024, according to a TCEQ spokesperson.

Broken Promises and Suspicious Emissions Numbers

Forty miles east of Port Neches, in Westlake, Louisiana, Indorama operates another facility with a similarly troubling record. The area surrounding the plant here is much like its Texas counterpart — a persistent toxic stench, smoky skies, and schools and homes close by.

After it bought the facility in 2015, Indorama made the same pledge to be a good neighbor in Louisiana that it had made in Texas. Then-Governor Bobby Jindal welcomed the company with a 1.5 million grant as well as a tax subsidy worth at least $73 million over 10 years, according to calculations by the nonprofit Together Louisiana. Indorama pledged to “meet or exceed all environmental regulations.” The company did not keep its promise.

The problems began as soon as Indorama started up the plant, which had been closed down in 2001.

Repeated mechanical failures led to emergency flaring at the facility in 2019. The flare belched black smoke into the community, roaring with such violence that it rattled the windows of nearby homes.

“It was like a 300-foot flame, and it went on for weeks,” said James Hiatt, director of a Lake Charles nonprofit called For a Better Bayou, at the time. “People couldn’t sleep at night.”

According to a Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality document, the vent flare of the facility burned for a total of 2,256 hours — or 94 days — in 2019.

The issues forced Indorama to shut the plant down in June 2019 before starting back up again. As it turned out, the company was also missing certain key permits for its facility.

Indorama quietly settled various environmental and compliance violations related to the bungled ethane cracker startup with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality this year and paid $175,000, according to a document published on the department’s website. The company was finally able to restart the ethane cracker in January 2020.

Roishetta Sibley Ozane lives less than a mile from Indorama’s Westlake facility. She is a mother of six and is concerned about the links between petrochemical plants and maternal health, including premature births and infant death. Ozane had a stillborn baby and several of her children have asthma.

“Indorama is a serial polluter,” she said. “I’m starting to realize that it’s my close proximity to these facilities and constantly breathing in this polluted air,” Ozane said about her and her children’s health issues.

She decided to purchase a special camera to show pollution that can’t be seen with the naked eye. “And it showed that Indorama was polluting way more than we even expected.”

Ozane said that she doesn’t understand why companies like Indorama only have to pay small fines when they release toxic chemicals that affect residents and the environment. “These facilities get to come here and pollute our air and our water, kill our children, cause us to have cancer and all these other different respiratory issues, and they’re not paying their fair share,” she said.

And emissions from Indorama’s plant are getting worse, a Hunterbrook data analysis shows. The company’s releases of known or probable carcinogens at the facility were four times higher in 2024 than in 2021, its first full year of operation. Emissions of 1,3-butadiene — a chemical linked to cancers of the stomach, blood, and lymphatic system — have increased tenfold.

The analysis also shows that the company kept violating its permits once the facility finally opened: Fugitive benzene releases were above emissions limits not only in 2020, but also in 2022 and 2023.

Fugitive emissions are the industry term for leaks that escape through valves, cracked seals, and loose connectors rather than being filtered through controlled smokestacks. In Louisiana, state data shows that large amounts of Indorama’s toxic releases come from these hard-to-track sources.

But a forensic review of the company’s filings suggest these numbers may be little more than fiction. For two consecutive years — 2022 and 2023 — the company submitted identical fugitive emission figures. Then, in 2024, the data became even more improbable: Indorama reported emitting exactly the same amount its permits allowed across a wide range of chemicals, down to the single pound.

A comparison with neighboring facilities underscores the anomaly. While similar plants in the area reported emissions with decimal-point precision, Indorama’s figures remained suspiciously static, despite the company enjoying permit limits significantly higher than those of competitors.

If Indorama indeed calculated its emissions inaccurately, surrounding communities would be left in the dark about the amount of toxic chemicals they are breathing in — and the company could potentially dodge fines for permit violations.

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality did not respond to a request for comment.

Residents in Louisiana are fighting back. Ozane decided to start organizing her community. She brought neighbors to city council meetings and police jury meetings, and even took a trip to Washington, D.C., to meet with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.

“We are literally fighting for our lives, trying to ensure that our children can breathe clean air and drink clean water,” she said.

“Dont Mess With Our Economy”

In Port Neches, however, speaking out against the petrochemical industry is sometimes viewed as civic betrayal. While a number of residents were happy to meet and share their stories with Hunterbrook for this article, others pushed back and defended Indorama vigorously.

“Ms New York, dont mess with our economy,” one resident wrote under a Hunterbrook reporter’s post on Facebook. “Somebody will run you out of town,” another wrote. “Go back to NY,” a third person commented under another Facebook query.

When a reporter knocked on the doors of homes near Indorama’s plant to talk about living in such close proximity to the facility, one resident threatened to call the police.

For many locals, raising concerns about Indorama isn’t simply about pollution or health risks; it’s about threatening the foundation of a city whose identity and livelihood are tied to the plant.

“It is the main economy,” Timothy’s mother said.

As an ICU nurse, Timothy’s livelihood doesn’t depend on Indorama. He dreams often of leaving Texas — of finding a place where the environment isn’t a daily hazard.

But for now, he stays for her.

He turned to his mother, the smell of the plant hanging thick outside.

“Do you know how nice it would be to wake up to clean air in the morning?”

Authors

Till Daldrup joined Hunterbrook from The Wall Street Journal, where he focused on open-source investigations and content verification. In 2023, he was part of a team of reporters who won a Gerald Loeb Award for an investigation that revealed how Russia is stealing grain from occupied parts of Ukraine. He has an M.A. in Journalism from New York University and a B.S. in Social Sciences from University of Cologne. He’s also an alum of the Cologne School of Journalism (Kölner Journalistenschule). Till is based in New York.

Michelle Cera trained as a sociologist specializing in digital ethnography and pedagogy. She completed her Ph.D. in Sociology at New York University, building on her Bachelor of Arts degree with Highest Honors from the University of California, Berkeley. She has also served as a Workshop Coordinator at NYU’s Anthropology and Sociology Departments, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and innovative research methodologies.

Evan Comen is currently the senior data editor at U.S. News & World Report, where he focuses on government rankings and accountability reporting. He has worked as a data journalist since 2015, covering climate change, urban economics, and public policy. Evan has a B.A. in economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and is based in New York.

editors

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a B.A. in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Graphic

Dan DeLorenzo is a creative director with 25 years reporting news through visuals. Since first joining a newsroom graphics department in 2001, he has built teams at Bloomberg News, Bridgewater Associates, and the United Nations, and published groundbreaking visual journalism at The Wall Street Journal, Associated Press, The New York Times, and Business Insider. A passion for the craft has landed him at the helm of newsroom teams, on the ground in humanitarian emergencies, and at the epicenter of the world’s largest hedge fund. He runs DGFX Studio, a creative agency serving top organizations in media, finance, and civil society with data visualization, cartography, and strategic visual intelligence. He moonlights as a professional sailor working toward a USCG captain’s license and is a certified Pilates instructor.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.