Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. Full disclosures below.

Eggs have become a status symbol — sold as loosies in New York City bodegas; dubbed the new caviar; climbing to a record average of $8.05 per dozen in February.

And that’s just for normal eggs, not even the organic, pasture-raised kind with the bright orange yolks.

As news of Americans reeling from sticker shock and empty egg shelves has dominated headlines, the industry has been quick to remind us they, too, have suffered.

“It’s been a devastating two years for the industry,” American Egg Board CEO and President Emily Metz told a trade publication recently. “Our farmers are fighting for their livelihood and their farms.”

Big Egg has emphasized that price hikes have coincided with mass outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza across the U.S. since 2022 — the longest-running and deadliest in the nation’s history.

But a months-long investigation by Hunterbrook Media, one of several published on the industry by various outlets this month, suggests bird flu may not have been solely, or even mostly, responsible for the increase in egg prices. And while some egg farmers were undoubtedly devastated by the flu, the largest players — across an industry that has been consolidating for years — have been clucking all the way to the bank.

At Cal-Maine Foods (NYSE: $CALM), the nation’s top producer, quarterly profits have been up an average of 948% since the calamities began in 2022, Hunterbrook compared profits reported by Cal-Maine in its quarterly SEC filings, starting with the filing for FY Q2 2022 (which covers the period from November 27, 2021, to February 25, 2022) with corresponding quarters that roughly fell in the 2021 calendar year, which included fiscal quarters Q3 2021, Q4 2021, Q1 2022, and Q2 2022. compared to the corresponding quarter in 2021.

The company’s stock price is up over 100%. A recent board decision to carry out a $500 million share buyback and allow the founding family members to sell their stock on the open market suggests insiders are gearing up to cash in.

Amid growing concerns of potential price gouging, the industry has defended its windfall as simple economics.

“It is deadly, it is devastating, and the impact that you’re seeing is a direct result of very, very tight supply and consistently high demand. Americans love eggs. So, we have a supply shortage and high demand and that’s why you’re seeing the prices you’re seeing,” Metz told Newsmax recently.

A deeper dive into the data exposes cracks in the industry’s narrative, however.

Sign Up

Breaking News & Investigations.

Right to Your Inbox.

No Paywalls.

No Ads.

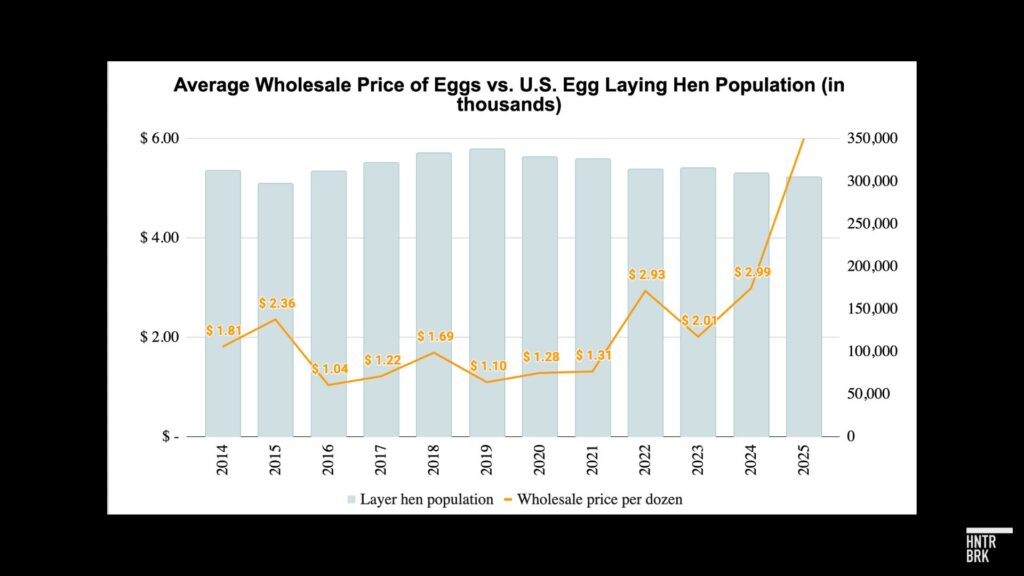

For starters, it isn’t the first time the industry has been hit by a massive bird flu outbreak. The monthly reduction in the egg-laying flock size since 2022 has been similar to those in 2015, when HPAI destroyed 43 million egg-laying hens.

And yet prices since 2022 have risen more than three times more per hen loss than they did during the earlier outbreak.

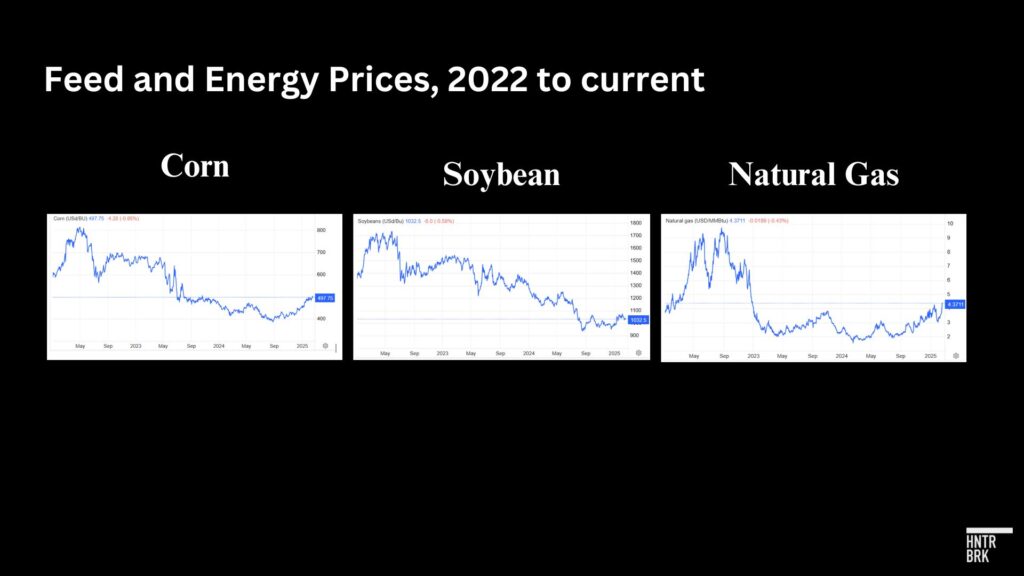

It’s not just avian flu, Metz told CNN NPR last September. “Inflationary pressures” are also at play, Metz said, pointing to operational costs that are “completely outside the control of the egg farmer.”

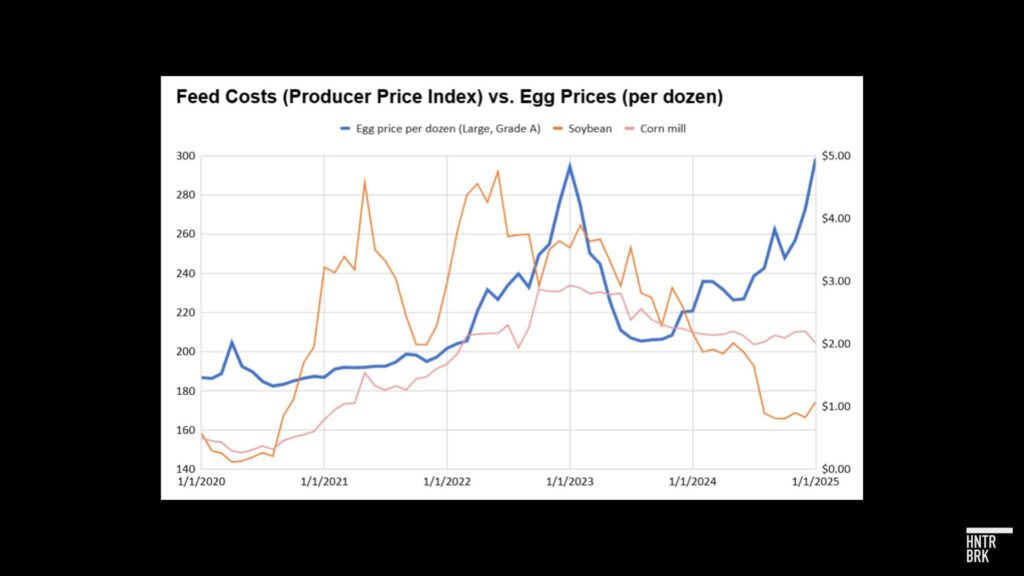

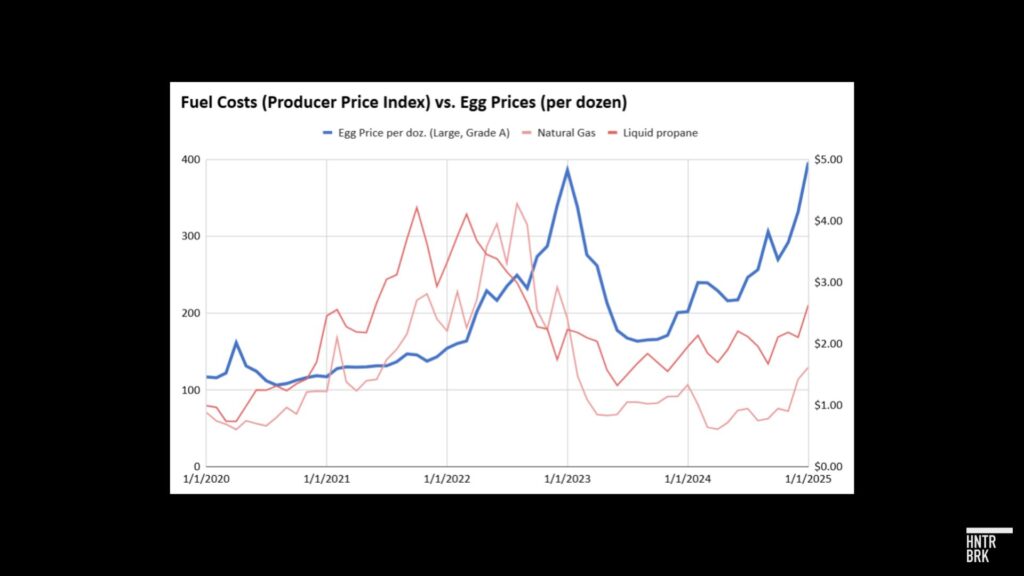

But feed costs, which account for roughly half of all production costs, have gone down significantly since 2022. The price of natural gas, one of the key fuels used for running egg farms, is also down.

Metz separately cited old fashioned “supply and demand” to explain egg prices, but that, too, does not seem to explain the full story.

“We do not see the supply and demand numbers that justify the prices being charged,” Joe Maxwell, co-founder of Farm Action, a farmers’ advocacy group, told Hunterbrook. Farm Action recently sent a letter to the Federal Trade Commission calling for an investigation of the egg industry, saying the actual impact of bird flu on production has been minimal.

“The minute we see a market not responding the way it should, that’s a flag for us to say, ‘OK, what is going on here?’ Because the market dynamics, the basic laws of economics, are not working,” said Maxwell.

He isn’t alone. Multiple state attorneys general have questioned whether egg prices really are dictated by competitive market dynamics, as the industry claims.

In a string of lawsuits filed against egg giants in recent years, states have zeroed in on a pricing system widely used in the egg industry. Unlike publicly traded commodities like soy, corn, or orange juice—whose prices are transparently set by exchange markets—egg prices are dictated in part by quotes from a private price reporting agency called Urner Barry, now also known as Expana.

The problem, alleged New York Attorney General Latitia James in a 2020 price gouging complaint against major egg producer Hillandale, is that Urner Barry calculates its quotes based on the inputs collected from the very egg producers that use its quotes to justify their prices — creating a game of telephone that is inherently vulnerable to manipulation.

“The function of Urner Barry’s pricing report during the coronavirus pandemic has been to allow producers such as Hillandale to capitalize on increased consumer demand during a crisis,” the attorney general claimed. Asked for comment, an Urner Barry spokesperson noted the Hillandale case was settled out of court. He said: “Whether they are going up or down, we do not set prices, we simply observe and report what is happening.”

“The UB Egg Index publishes data on trades in the spot market. It is a data set; it does not influence producers any more than, say, the S&P 500 going up or down influences investors to buy or sell shares,” the spokesperson added.

The growing market power of the leading egg producers — a result of decades of market consolidation through aggressive acquisitions — hasn’t helped ease suspicions of price gouging, either.

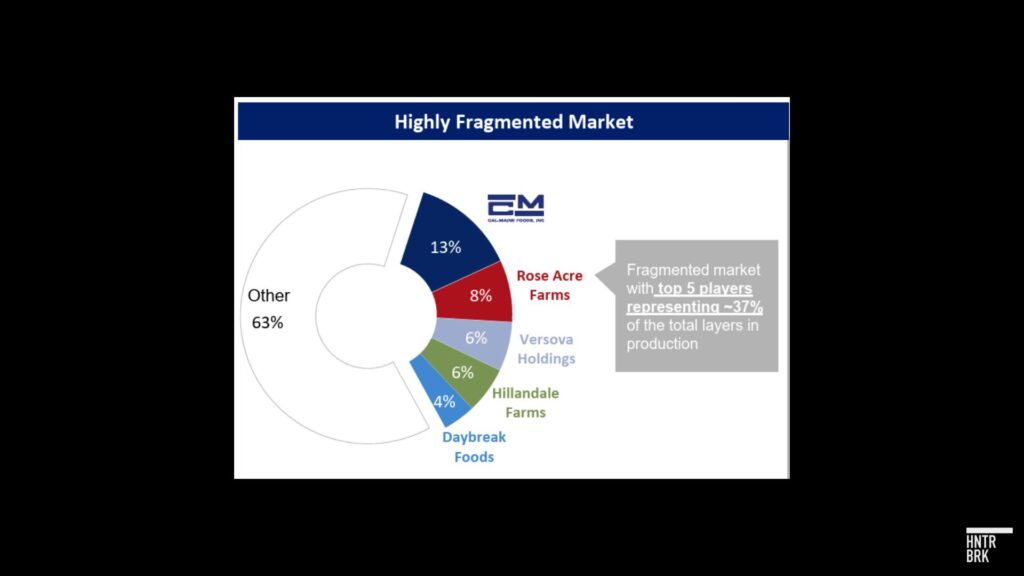

Indeed, with the four largest companies now controlling nearly 40% of the market, the egg industry is approaching the threshold established by some economists to determine concentrated markets.

In 2023, a federal jury found leading egg producers including Cal-Maine guilty of colluding to fix prices and reduce supply in a lawsuit filed by Kraft Foods and other food companies. A report released by Food and Water Watch, a consumer advocacy group, just a few days ago largely mirrors Hunterbrook’s findings on Urner Barry and the potential risks posed by industry consolidation to competitive pricing.

It’s one of the few issues where the Trump administration and Congressional Democrats have expressed similar concerns.

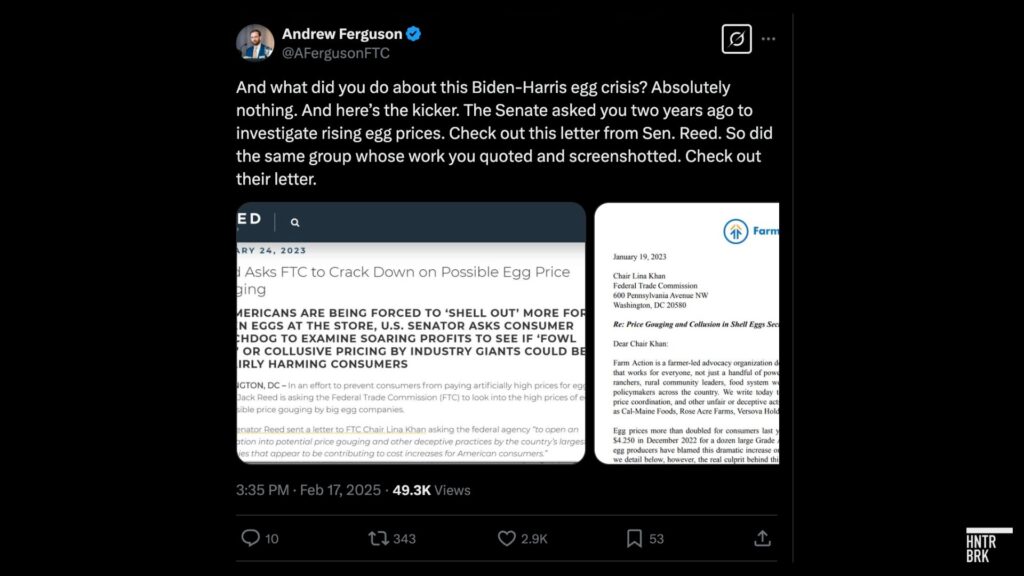

Sen. Jack Reed, a Democrat from Rhode Island, in 2023 urged the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice to investigate potential price gouging by egg producers — calling out Urner Berry in particular.

“Industrial egg producers seem to be feeding the American public a phony narrative about why egg prices are so high and could be using anti-competitive pricing tactics to force consumers and retailers to shell out more for eggs,” read a press release from Reed’s office.

“While the wholesale price of eggs is tied to the Urner-Barry index, the dozen largest egg producers have the ability to feed data into the index that could result in beneficial pricing for the industry,” Reed added.

Reed repeated the plea for the FTC and DOJ to open an investigation to President Donald Trump last month.

In a recent X post, newly appointed FTC chair Andrew Ferguson harshly criticized the FTC under the Biden administration for failing to investigate the egg industry, suggesting the new administration may be gearing up for action.

None of the top five egg companies Hunterbrook reached out to for comment responded.

What’s the Difference Between Price Gouging and Inflation?

The avian flu outbreak in 2022 did put a serious dent in the U.S. egg-laying flock. The industry lost about 44 million hens in late 2022, followed by 14 million more in late 2023 and — after a yearlong lull — 63 million more as of February this year.

The numbers have been so mindbogglingly large because HPAI is extremely infectious. The USDA — in line with World Animal Health Organization recommendations — has mandated the culling of entire premises if a single infection is detected. Given the massive scale of many commercial egg farms, just one farm could contain millions of hens.

There are “simply not enough chickens laying eggs in the U.S. right now to cover the level of demand that we’re seeing,” Karyn Rispoli, managing editor at Urner Barry, said in an Expana video on YouTube regarding elevated egg prices in August. People in the industry have told her it’s “unlike anything they’ve ever seen before,” she said.

Compounding the effect of supply cuts on egg prices is the fact that egg demand is notoriously price inelastic, economists say, meaning people don’t cut back when prices increase. That means a change in supply could cause an outsized swing in pricing.

But even accounting for historical trends in the price inelasticity of egg demand, prices in the last three years have gone up wildly, disproportionate to actual reductions in supply.

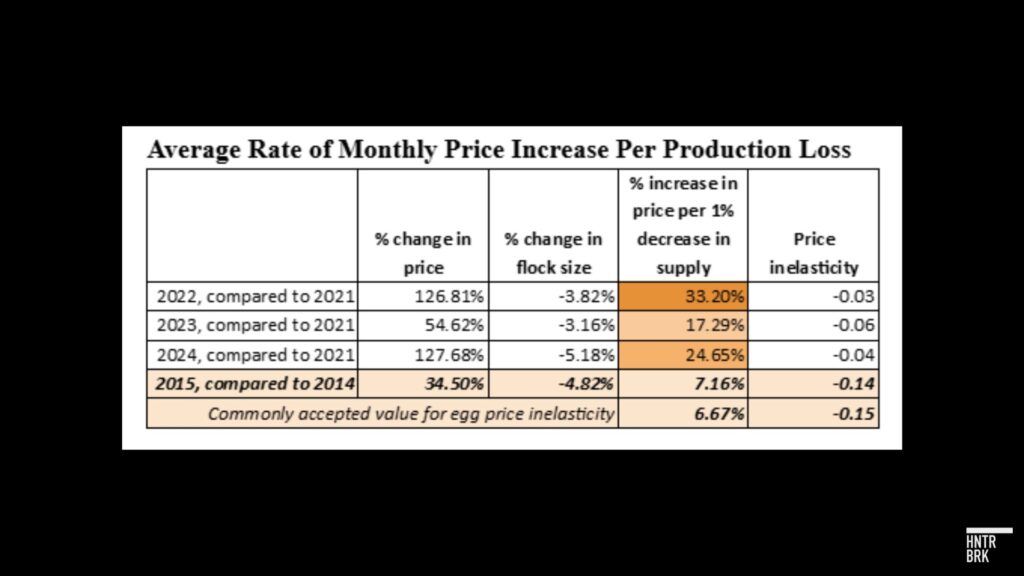

According to the latest analysis of USDA inventory data by Farm Action, the average monthly total U.S. egg-laying hen flock — a commonly cited proxy for the egg supply — was “on average only 3.82% smaller in each month of 2022, 3.16% smaller in each month of 2023, and 5.18% smaller in each month of 2024,” compared to the corresponding month in 2021, before the bird flu outbreak.

That’s because, as antitrust lawyer Basel Musharbash explained in a 2024 study he conducted on the monopolization of the agricultural industry for Farm Action, the hens “were not lost all at once, and there were always over 300 million other hens alive and kicking to lay eggs for America” in 2022. It took about seven to nine months to repopulate farms in 2015.

For example, Cal-Maine lost a total of 3.7 million chickens to avian flu in two of its facilities in Kansas and Texas in December 2023 and April 2024, but by early November had added 8 million hens to its flock, more than recovering from its losses in just six months.

In fact, Cal-Maine’s flock as of last November, at a total of 60.1 million, was 15% higher than it was before 2022.

Moreover, the actual domestic egg supply fell even less than the flock size, due to a significant reduction in egg export and an unprecedented increase in laying rate per hen, owing to improved genetics.

Accounting for these factors, the effective reduction in flock size in 2022 was only 3.5 million laying hens — or about a 1% decrease — compared to 2021, according to a presentation by Egg Industry Center researcher Maro Ibarburu at a USDA-sponsored conference in 2023.

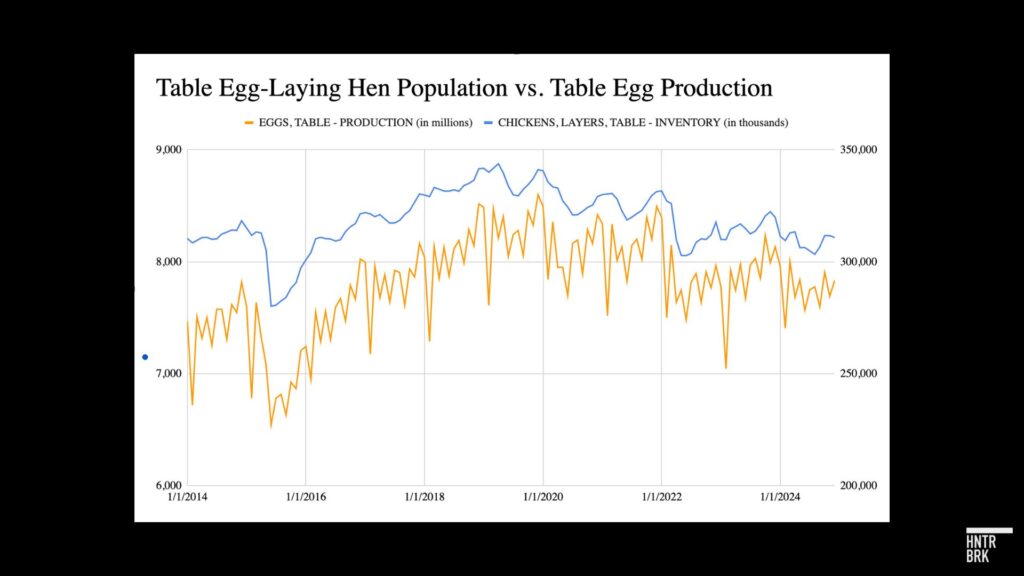

Egg production per hen has improved significantly since 2022, suggesting that hen losses have had a disproportionately smaller impact on the egg supply compared to previous years, as shown by the narrowing gap between the two trend lines.

And yet, the national average wholesale prices in the same month-to-month comparison to 2021 rose 127% in 2022, 54.6% in 2023, and 127.7% in 2024, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of USDA wholesale egg price data.

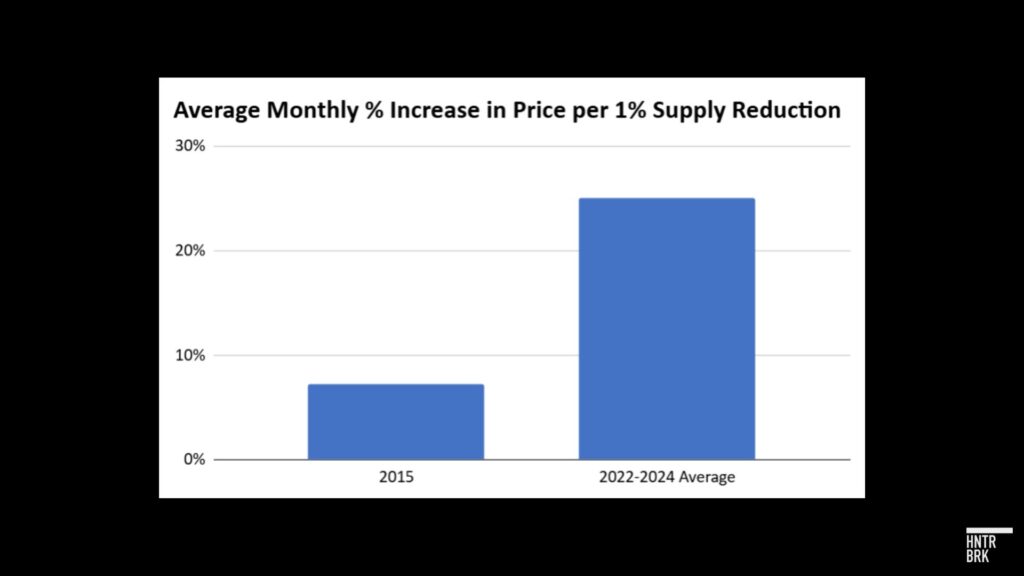

These numbers imply a 33% increase in price per 1% decrease in supply in 2022, a 17% increase in price per 1% decrease in supply in 2023, and a 25% increase in price per 1% decrease in supply in 2024.

That’s on average more than three times the rate of price increase per supply loss in 2015, when prices rose 7.16% per 1% layer hen loss — a rate more consistent with the commonly assumed value for the price elasticity of egg demand of 6.67% increase for every 1% reduction in quantity, according to Jayson Lusk, agricultural economics professor at Oklahoma State University.

The U.S. egg price spike is even more puzzling when compared to Europe, which also saw a massive supply shortage in 2022 after 50 million layers were depopulated — compared to 43 million in the U.S. And yet, prices only rose about 30% in Europe from January 2022 to January 2023, compared to nearly 170% in the U.S.

Did Demand Change?

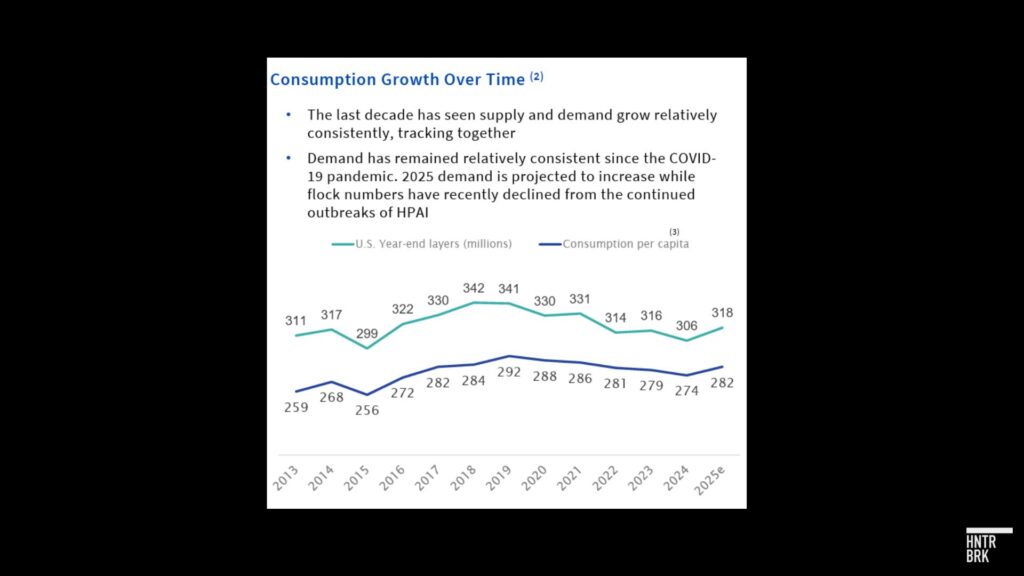

A significant change in the demand might explain the discrepancies. A switch in consumer preferences — say, because of a new fad diet — could further steepen the demand curve for eggs and make the price more inelastic.

But that doesn’t seem to have been the case, according to Cal-Maine’s statistics that show demand has moved largely in parallel with the trend in supply.

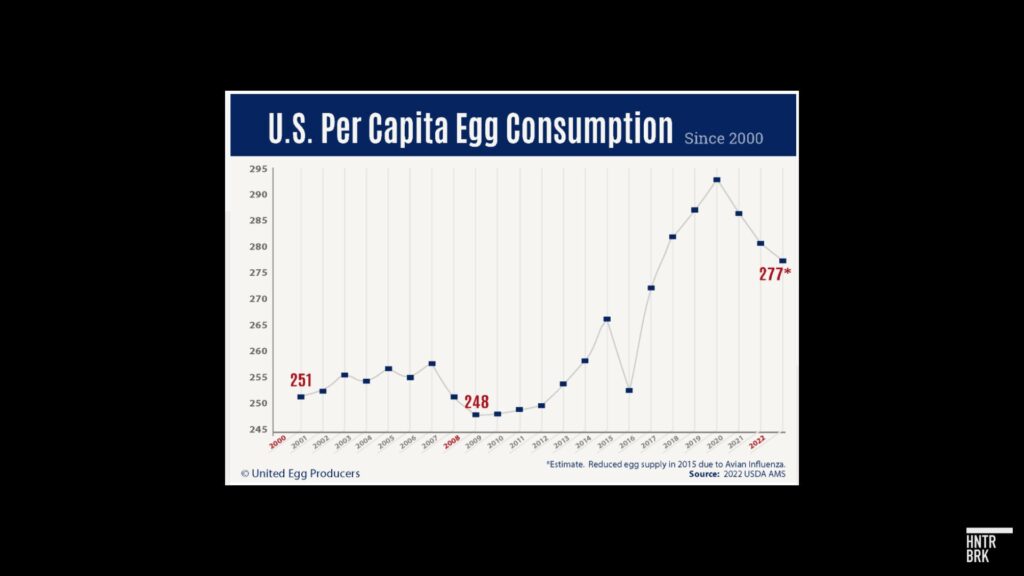

A chart compiled by United Egg Producers, the industry’s premier trade association, also shows a noticeable dip in egg consumption per capita since 2019.

Did Production Costs Soar?

Production costs can be a leading factor influencing prices in a competitive commodities market.

In fact, Metz told the Associated Press in 2023 that she believed the cost increases farmers had faced the previous year had played more of a role than bird flu in price increases. “When you’re looking at fuel costs go up, and you’re looking at feed costs go up as much as 60%, labor costs, packaging costs — all of that … those are much much bigger factors than bird flu for sure.”

But feed costs, which account for the majority of production costs of eggs, have been largely going down since 2022 as well.

The cost of propane and natural gas, the most common type of fuel in poultry farming, are also down.

Cal-Maine’s quarterly and annual statements also show production costs have gone down by over 17.5% from their peak in mid-2023 to the end of 2024, even as the prices the company charged for its eggs continued to climb.

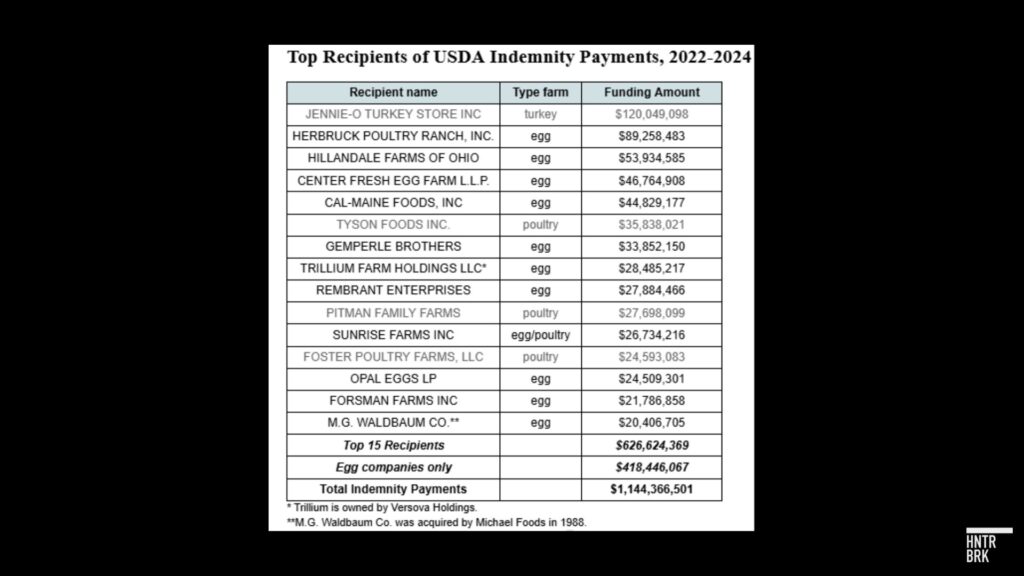

The industry also received $1.1 billion in taxpayer-funded indemnity payments from the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service since 2022 to help offset costs. The payment covered up to 100% of the “fair market value” of the lost hens — or the estimated revenue from the eggs that the layers would have produced — as well as “feed, depopulation and disposal costs, and virus elimination costs.”

More than half of the total indemnity payments went to the top 15 recipients, the majority of which were the largest commercial egg producers running massive-scaled operations housing millions of hens.

A Cal-Maine executive told investors last November that the indemnity program “takes some of the sting, but by no means would it compensate for lost income.

“But I haven’t seen any desperate bankruptcy situation.”

Indeed, the largest egg producers’ continued spending spree to further expand their operations seems like anything but a bankruptcy situation.

Since 2023, Cal-Maine has acquired two separate assets — ISE America Inc. and Fassio Farms, adding 4.7 million and 1.2 million layers, respectively, to its flock. Rose Acre Farms broke ground in 2023 on a new $100 farm in Arizona to operate 2.2 million cage-free hens and announced in 2024 that it was in the process of adding cage-free farms in Indiana to house 1.2 million to 1.3 million hens. Daybreak Foods, ranked fourth-largest, acquired two operations — Hen Haven LLC and Schipper Eggs LLC — in 2023.

Are Egg Producers Charging More for Eggs because they can?

So if market conditions like a significant demand increase, supply reduction, or rise in production costs don’t fully explain the dramatic price increases, what does?

“It’s a head scratcher for us,” said Russell Diez-Canseco, CEO of Vital Farms (NASDAQ: $VITL) — which distributes premium, free-range eggs — in a 2023 interview with Yahoo Finance. “I don’t see anything in my cost structure that would have led me to raise our prices by as much as you’re reporting. We’ve taken just enough price to keep ourselves whole and continue to pay our farmers an appropriate profit for the work they do. I’m not suggesting anybody’s price gouging. I’m just saying I can’t explain why prices have gone as high as they have.”

Vital Farms’ revenue has also surged since 2022, with its stock price up nearly 70%. However, unlike Cal-Maine, Vital Farms’ margins have remained relatively stable. This is because it sells pasture-raised premium eggs, which were less affected by the extreme price volatility characterizing the conventional egg market.

An Urner Barry analyst offered the answer might be “psychology” in a weekly roundup video last year. The “participants are perpetually aware of HPAI,” he explained, referring to bird flu. Everyone is more “confident about the value they can offer to the market.”

In other words, producers are charging higher prices for eggs because they can.

Which is what differentiates inflation from price gouging, according to the Harvard Business School. While “inflation is a general increase in prices” due to market dynamics over time, price gouging “is often the result of a business decision.”

Cal-Maine’s recent presentation to its investors hints at such a business strategy by touting consumer tolerance for price hikes.

What Is Urner Barry and How Do Egg Producers Price Their Eggs?

Amid mounting complaints of price gouging, Cal-Maine has explained that it doesn’t control retail prices.

“We are a producer and distributor and do not sell eggs directly to consumers,” said the company’s CEO. “The majority of our conventional eggs are sold based on market quotes published by Urner Barry, an independent, third-party market reporter.”

The egg market — unlike those for other agricultural commodities like soy, coffee, and sugar — does not have a regulated market exchange where eggs are openly traded and prices are discovered. Instead, producers largely use the daily price quotes provided by Expana, as a baseline for their own pricing in contracts with their buyers.

There is an online spot market, called the Egg Clearinghouse Inc., where farmers can offload excess inventory or buy more eggs to fulfill existing contracts in a crunch. But only about 5% of eggs are traded through the Egg Clearinghouse. Whether the prices discovered through the ECI is an accurate reflection of real market dynamics is an open question. “The top firms control so many of the eggs they can manipulate even the spot market price,” Maxwell told Hunterbrook. A 2005 research paper appearing on the Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics also noted that “thin” markets like the Egg Clearinghouse where only a marginal number of players utilize the market raises concerns that “transacted and reported prices may no longer represent overall supply and demand conditions.” “The potential impacts of individual transactions on price in thin markets create incentives for price manipulation,” the paper explained. For example, a firm that needs to buy eggs could first sell eggs on the exchange to dilute prices. The study showed that at least one firm bought and sold on the same day on the ECI more than 50% of the trading days in 2021.

The ECI was founded by Cal-Maine founder Fred Rogers Adams, Jr. in 1971. Adams’ son-in-law Adolphus B. Baker, who has served as Cal-Maine’s chairman since 2012, previously served as the chairman of the ECI and continues to serve on its board of directors.

For its part, Urner Barry takes the prices discovered through the Egg Clearinghouse, as well as information it collects daily from the producers and other industry participants like distributors and retailers, to come up with its own quotes.

“While ECI is a fantastic platform, they provide a great amount of transparency, but it rarely paints the entire picture, and that’s where we come in,” Urner Barry analyst Rispoli explained in a recent podcast.

Urner Barry asserts that it adheres to strict methodologies and international standards to collect impartial pricing data. An Urner Barry spokesperson told Hunterbrook, “We guard against the risk of manipulation by adhering to the IOSCO methodology,” adding that IOSCO, the International Organization of Securities Commissions, is a “global association of securities regulators whose job is to protect investors, promote fair and efficient markets, and reduce systemic risk.”

“Leading accountancy firm BDO audits UB annually for compliance with IOSCO standards. We have passed every audit.”

That fact, however, may not mean as much as Urner Barry thinks it does – according to recent reporting by Bloomberg, “Two-thirds of [BDO’s] audits picked for inspection [by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board] fell short of U.S. standards in BDO’s most recent report,” leading the firm to make substantial changes in its auditing process.

Regardless, regulators warn of the inherent risk of manipulation in the system due to the price reporter’s close, circular relationship with egg producers — its own customers.

In 2020, the Texas attorney general filed a complaint against Cal-Maine for price gouging during the COVID-19 pandemic — a violation of the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices-Consumer Protection Act. The complaint alleged that the company had misrepresented matters by claiming that its prices were based on “market quotations” that were “outside of our control,” which implied there was a regulated “market.”

“In fact, there is no egg market exchange,” the attorney general wrote. Instead, “a company called Urner Barry publishes an industry newsletter” and “publishes various price indexes” based on information from companies that submit data voluntarily.

Moreover, “as a vertically integrated company, Cal-Maine controlled its own pricing,” the attorney general argued, according to a local law blog.

The trial date is currently set for August 11.

Texas isn’t the only state to object to the industry’s claims about the independence of Urner Barry’s price quotes.

New York State Attorney General Letitia James also made a similar argument in a 2020 case against the country’s fourth-largest egg producer, Hillandale Farms. The lawsuit alleged that the company had engaged in price gouging during the COVID-19 pandemic. James noted that Urner Barry’s “indices work like a feedback loop” and egg producers such as Hillandale then used Urner Barry’s indexed prices as justification for charging “unconscionably excessive” prices during a crisis.

Hillandale settled that case the next year by promising to no longer engage in price gouging and donating 1.2 million eggs to food banks.

Others have gone further, accusing Urner Barry of actively facilitating price-fixing and other conspiracies by agricultural industries in violation of U.S. antitrust laws.

The State of Alaska in 2021 accused Urner Barry as well as Agri Stats for aiding the poultry suppliers in “their anticompetitive output restriction scheme” by serving as a “conduit for the sharing of information and ensuring the compliance with production cutting scheme.”

The complaint, which targeted broiler chickens rather than egg producers, argued that industry-wide events, such as Urner Barry’s annual marketing seminars and executive conferences gave poultry producers “additional opportunities to meet and discuss their collusive efforts to reduce Broiler production.”

Urner Barry’s role in anticompetitive practices has been featured prominently in cases brought on by private actors as well. In a major antitrust case against broiler chicken producers by retailers like Kroger and Albertsons in 2017, the plaintiffs claimed that the defendants directly influenced Urner Barry’s price calculations by submitting misleading or selective pricing data and pressuring a key executive at Urner Barry to raise prices. The case has led to over $280 million in settlements to date.

Federal regulators, too, are taking their suspicions about the inherent antitrust risks associated with private price quoting agencies to court.

In a landmark case filed in 2023 by the Department of Justice and six state attorneys general that did not directly name Urner Barry, regulators alleged that Agri Stats — another agricultural price quotation company — had violated the Sherman Antitrust Act by sharing “competitively sensitive information related to price, output and costs.”

The “Mystery” of Conventional Egg Prices Rising More Than Cage-Free Egg Prices

Recent economic data seems to suggest that price quotes in some cases allow producers to charge higher prices than they would without the quotes.

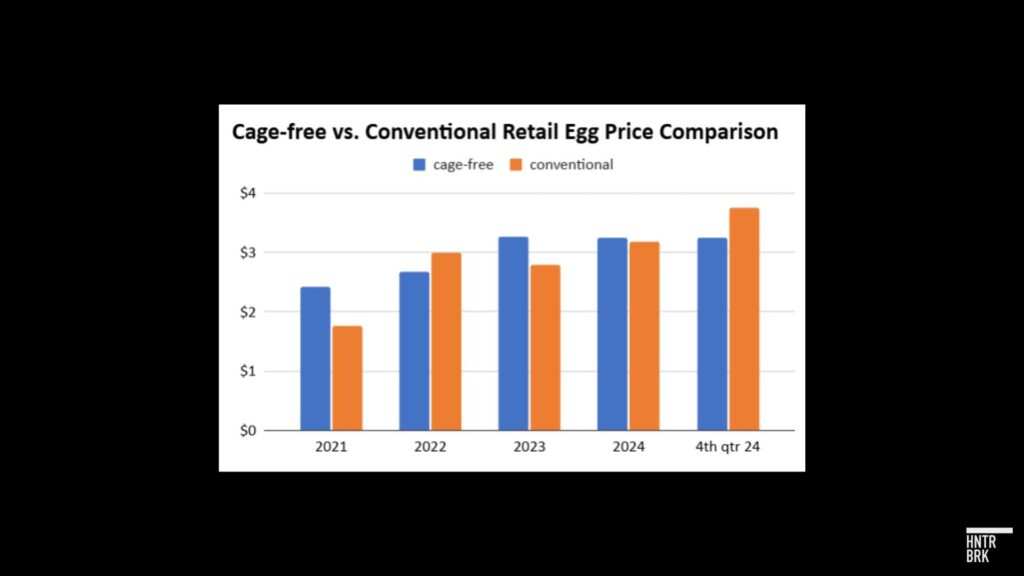

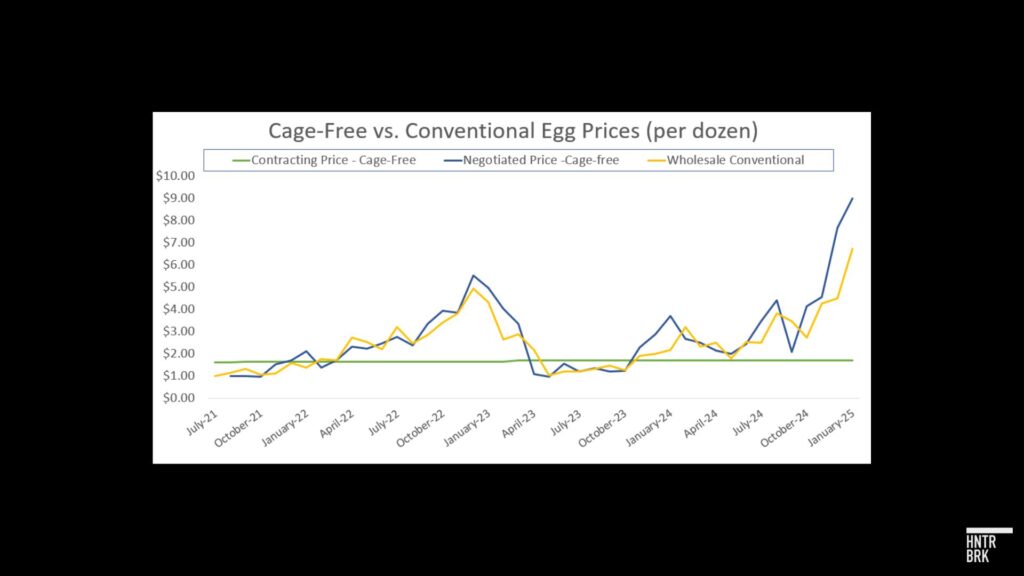

An analysis of egg prices shows that conventional egg prices, most of which are tied to Urner Barry quotes, rose more sharply than cage-free eggs, which are more often dictated by long-term contract pricing that are based on production costs.

The average price for cage-free eggs in the five months before the 2022 outbreak were about $0.65, or about 36%, more than conventional eggs. The typically higher price of cage-free eggs reflects higher capital ,labor, and feed costs of raising cage-free systems compared to conventional facilities, according to the Iowa Farm Bureau.

In 2022, however, conventional eggs were on average $0.33 higher than cage-free eggs. In 2023 and 2024, cage-free eggs were only 17% and 2% higher than conventional eggs, respectively.

Managers of small co-ops and specialty brands in 2023 noted that their egg prices rose far less during the recent spike, around 30%, compared to the 138% surge seen in commodity egg prices over the year.

It’s possible this reflects a lag in prices with long-term contracting, said Dan Scheitrum, an assistant professor of agribusiness at California Polytechnic State University, told Hunterbrook.

Indeed, negotiated cage-free egg prices have been much more volatile than contracted prices since the 2022 outbreak, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of USDA data on cage-free egg prices. But even negotiated cage-free egg prices still rivaled wholesale conventional prices through much of the pandemic, even surpassing conventional egg prices at times.

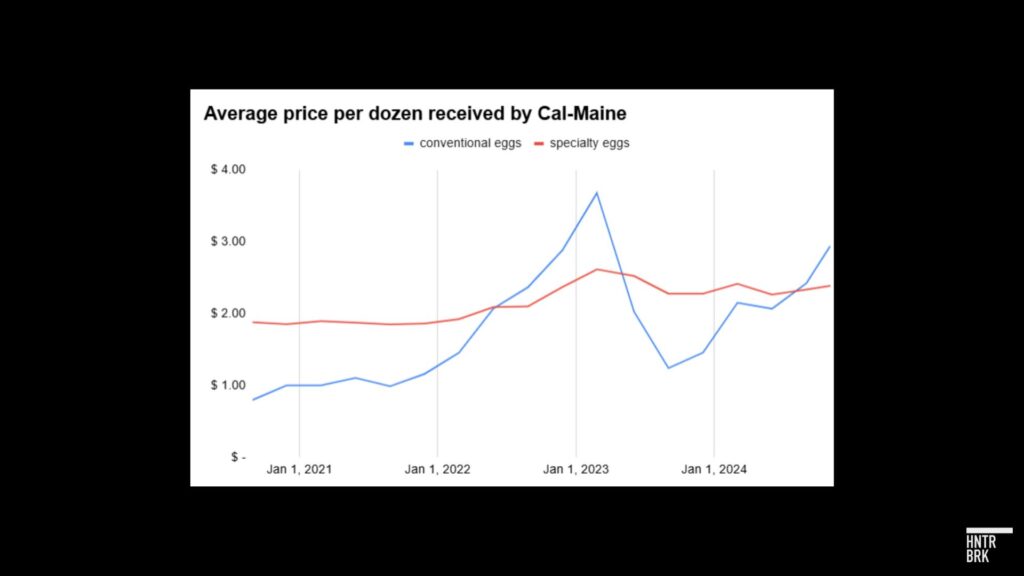

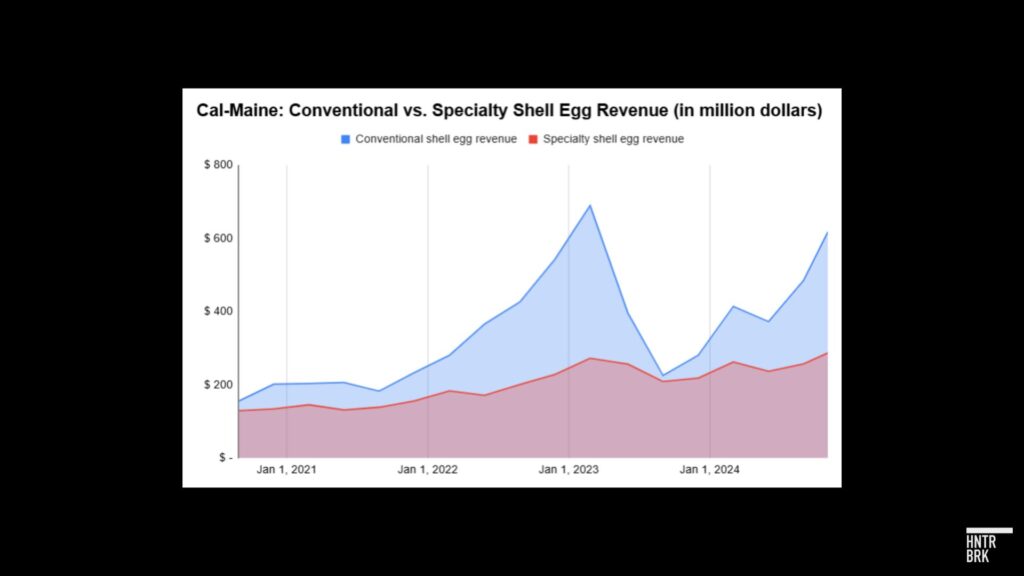

For Cal-Maine, too, which uses Urner Barry quotes for its conventional egg prices but not for specialty eggs, the difference in pricing is hard to miss. Since 2022, Cal-Maine’s average price per dozen received for specialty eggs each quarter remained relatively flat, around the $2 range, while its conventional egg prices rose more sharply in 2022 and again in 2024, even surpassing cage-free egg prices in certain periods.

The significant upswings in conventional egg prices allowed Cal-Maine to pad earnings during those peaks, while the revenue from specialty eggs stayed relatively constant.

Egg Industry’s Rapid Consolidation Drawing Antitrust Concerns

To measure a market’s competitiveness, economists often use the “four-firm concentration ratio,” or “CR4,” which is the combined market share of the top four companies in the market. While there is no consensus, a CR4 of 40% or above is sometimes seen as the threshold for a possible oligopoly.

Oligopolies are a concern for antitrust authorities because of the risk a small number of firms could influence prices and coordinate among each other at the detriment of consumers, according to a study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

As of last November, the top four companies accounted for 39% of total egg-laying hens in the U.S., according to Cal-Maine.

That’s up from the top four egg producers controlling 33% of the layer flock just a little over four years ago.

The consolidation of the egg market follows decades of mergers and acquisitions of smaller farms by the largest egg producers. In 1978, 30 companies owned 1 million or more egg-laying hens, representing 27% of the nation’s laying hens. By 2023, those numbers had climbed to 54 companies with 1 million or more hens, representing 98% of the nation’s total flock.

A recent court decision echoes these antitrust concerns that the largest egg producers may have exerted their growing market power to manipulate prices.

In last year’s ruling on a case that began in 2008, a federal jury found Cal-Maine and the nation’s second-largest egg producer, Rose Acre Farms, guilty of participating in a price-fixing scheme from 2004 to 2008 in violation of federal antitrust laws. The lawsuit, brought by Kraft, Nestlé, and other food-processing giants, accused the egg companies of playing “key roles” in a conspiracy organized by the United Egg Board, the industry’s trade association, to restrict the national egg supply.

A Cal-Maine executive wrote in a United Egg Producers newsletter urging members to “‘do [their] part and make [the] industry profitable for everyone’ through the ‘total disappearance’ of 201.1 million old hens,” court documents said.

Cal-Maine and the other defendants were ordered to pay $17.7 million in damages — an amount that can be tripled to more than $53 million under federal antitrust law — to the defendants.

Not everyone agrees these legal outcomes offer proof of industry collusion, however.

Daniel Sumner, agricultural economics professor at the University of California, Davis, told Hunterbrook that the “economic evidence in favor of a conspiracy was incredibly weak.”

“I mean, it was things like … they stayed in the same hotel … and then they said, ‘Look, they all raised their price at the same time,’” he said. “I do not rule out that there are crooks in the business. In recent years, I haven’t seen evidence of that sort and I haven’t seen any in the sort of general economic evidence suggesting that they have manipulated prices.”

In any case, industry consolidation is showing no signs of slowing down, despite challenges posed by the avian flu. In fact, it may have accelerated the market dominance of the biggest players.

In 2023, the top 63 U.S. egg producers had 9.17 million more hens than in the previous year, according to a Watt Poultry survey. This suggests that the losses disproportionately affected smaller farms.

One reason may be that the largest producers, including Cal-Maine, are vertically integrated and also breed their own hens, which means they are able to repopulate their hens more quickly than smaller farms that rely on external supplies of hatching eggs.

A backlog on hatching eggs — with just two breeding companies providing 94% of all breeder stock for egg laying hens, according to The Atlantic — has forced other farms to wait over three months to repopulate their flock.

The industry’s consolidation may also have driven higher egg prices in more indirect ways as well.

“When you have a highly concentrated industry, that means there’s a lot of production coming from a relatively few number of producers,” Scheitrum explained.

“Detection of a single instance of bird flu is going to have a larger percentage supply reduction than if we had many smaller operations.”

The large size of the facilities also make biosecurity measures more difficult to achieve.

Eric Gingerich, poultry health consultant who has closely followed the avian flu outbreak, told Hunterbrook that “these large complexes are where we’re seeing the problem.”

“There’s a lot more traffic on these larger farms compared to a small 20,000-bird farm,” Gingerich explained. “A lot of them have feed mills on site and some days, during harvest, they’ll have 300 trucks coming into an operation every day. And that’s a lot of traffic. It could pick up virus on the roadways, that they could track it into the houses.”

The massive death toll from each outbreak in the U.S. stands in stark contrast to operations in Canada, which have much smaller farms, averaging about 25,000 hens per farm, Bruce Muirhead, public policy research chair at the Egg Farmers of Canada and a professor at the University of Waterloo, told CBC Radio Canada. He surmised egg pricing there would not imitate the pattern in the U.S. because Canada has smaller egg farms and a supply management system.

Not everyone is OK with the idea of U.S. taxpayers paying over a billion dollars to subsidize the risks inherent in the business strategy of large commercial egg farmers.

“Why should this high-risk business be bailed out?” Crystal Heath, animal rights advocate who has closely tracked indemnity payments, told Sentient Media in January.

Egg producers seem to disagree. A team of executives from major egg companies codenamed the “DC Strike Team” recently paid a visit to the Capitol to demand more indemnity payments.

Shortly after the visit, members of Congress sent a letter to the USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins requesting more in indemnity payments, saying the current rates are “based on inaccurate data and are artificially low.”

“We support a proposal by the egg industry to revise these calculations … to make indemnities fairer,” the letter said.

A few days later, on February 26, the Secretary announced the USDA’s plans to invest $1 billion to combat avian flu, including $400 million “to farmers to increase indemnity rates and allow farms to quickly return to business after an outbreak.”

The administration has not, however, announced steps to crack down on industry consolidation — or to lower prices.

Authors

Jenny Ahn joined Hunterbrook after serving many years as a senior analyst in the US government. She is a seasoned geopolitical expert with a particular focus on the Asia-Pacific and has diverse overseas experience. She has an M.A. in International Affairs from Yale and a B.S. in International Relations from Stanford. Jenny is based in Virginia.

Julia Case-Levine is a journalist, writer, and podcast producer based in Brooklyn. She has produced Signal-Award winning podcasts for Campside Media, and has written for The Nation, Bookforum, Quartz and elsewhere. She has a BA in History from Princeton University and an MA in Journalism from New York University.

Vibhor Mathur is a Brooklyn-based writer, researcher, and storyteller. His work extends comedy, journalism, film, and new media. He has contributed to work featured in TIME, Sports Illustrated, The Boston Globe, and elsewhere.

Editors

Jim Impoco, the editor-at-large at Hunterbrook Media, is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has an M.A. in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets. He has a B.A. in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.