Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time.

Are you ready for your mind to be blown? How about harvested?

BrainCo, a neurotechnology company that branded itself as Harvard-founded, has apparently harvested brain wave data from schoolchildren and elite athletes — including the world’s #2 tennis player, Formula 1 champions, and Olympic gold medalists. Its flagship products — wearable EEG headbands — collect and analyze brain wave data of the users to help improve their focus, the company claims.

The problem: BrainCo has quietly been funded by the Chinese government and government-linked entities, including a sanctioned military contractor, for almost a decade.

The company — which is preparing to go public at a $1.3 billion valuation, according to Bloomberg — built its reputation on Harvard credentials. Founded at the Harvard Innovation Labs. Advised by then dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. Staffed by a team from “Harvard University and MIT Brain Science Center.”

But a cross-continental Hunterbrook Media investigation — from Taipei to Cambridge — in collaboration with Pablo Torre Finds Out reveals that the Chinese government has been backing BrainCo since its early days in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

That was long before Beijing’s announcement of its major goal this year: leading the world in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology by 2030.

Sign Up

Breaking News & Investigations.

Right to Your Inbox.

No Paywalls.

No Ads.

China’s BCI roadmap, published in August, details an ambitious plan to achieve major breakthroughs in BCI — a technology that “enables communication between the brain and external devices by using thought alone” — including by nurturing two or three domestic companies to become global leaders in the field.

BrainCo fits the mold.

Since BrainCo’s Series A in 2016, state-owned enterprises — including a sanctioned defense contractor — have poured millions of dollars into BrainCo.

Despite continuing to highlight its presence in the “Greater Boston Area” and claiming to be “within walking distance of MIT, Harvard, and other leading institutions” on its website, BrainCo has in fact moved its headquarters to Hangzhou’s “Future Sci-Tech City” — an incubator explicitly designed to marry commercial and defense applications, where companies are promised special government support for technologies deemed critical to military dominance.

And in the last several years, BrainCo has been named one of Hangzhou’s “Six Little Dragons,” a title for its most prized tech startups, along with AI powerhouse Deepseek and robotics leader Unitree, and hosted visits from top Chinese officials.

In 2023, Premier Li Qiang — the CCP’s #2 official — visited BrainCo’s offices. This spring, Hong Kong’s chief executive, John Lee, known for squashing democratic protest, stopped by. Now, BrainCo’s founder Bicheng Han sits on Lee’s advisory board, tasked with providing advice on strategic matters.

The Hangzhou office may be also where BrainCo stores its trade secrets — technology developed by American researchers, with brain data that appears to be collected from world famous athletes and schoolchildren around the globe, Hunterbrook’s investigation suggests.

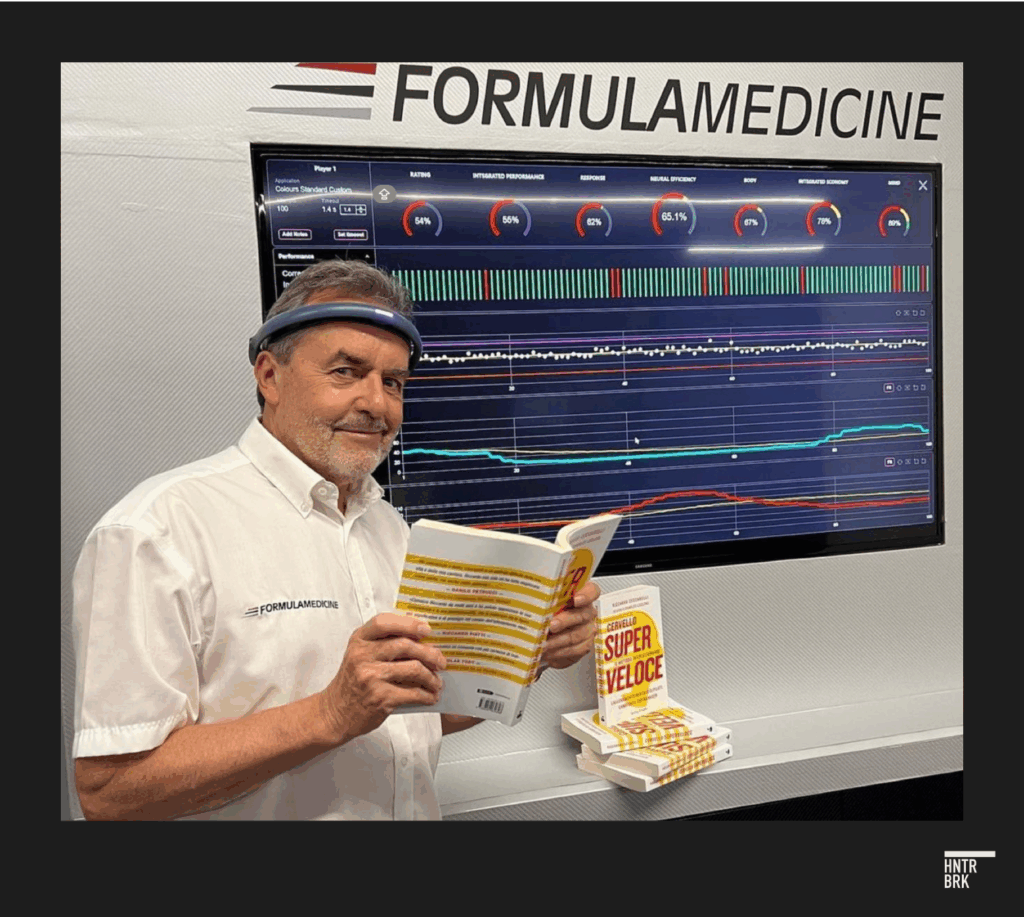

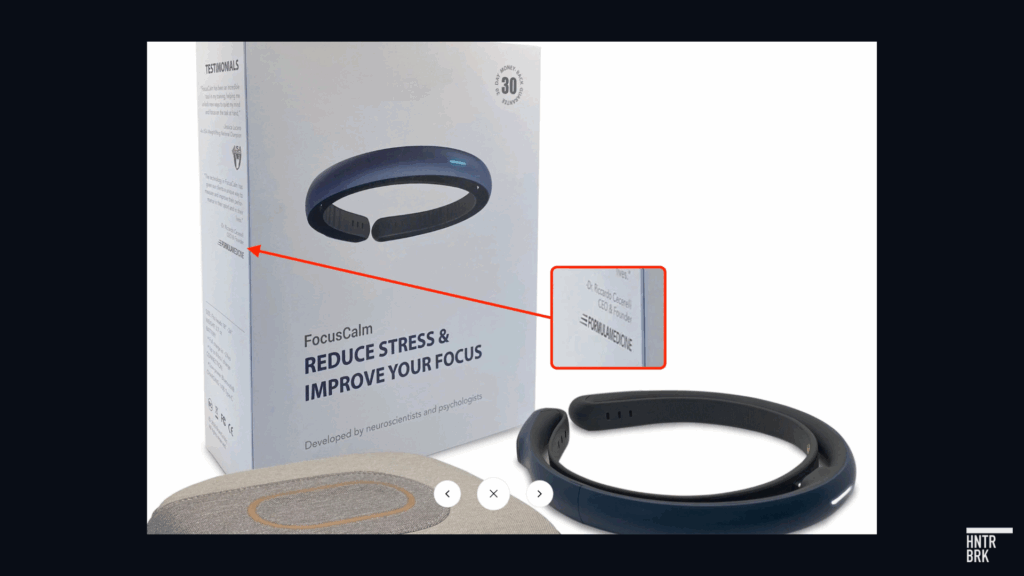

A BrainCo spokesperson denied the company collects any brain data from its customers, telling Hunterbrook in an email that such data is “purged from the application at the conclusion of each use.” However, Formula Medicine founder and one of BrainCo’s highest-profile customers, Dr. Riccardo Ceccarelli, told Hunterbrook that brain data from the athletes he helps train with BrainCo’s devices is saved in the “cloud.”

Multiple documents reviewed by Hunterbrook also contradict BrainCo’s statement.

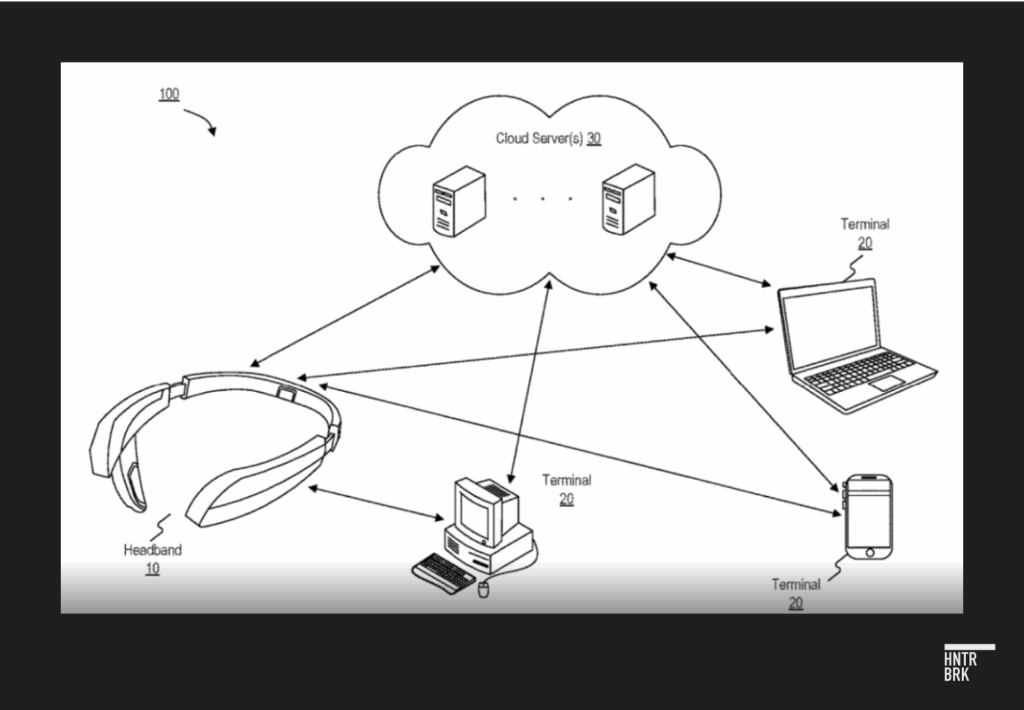

They include: BrainCo’s privacy statement explicitly saying it collects brain wave data from users and that aggregated data may be sent to any office worldwide or even third parties; a U.S. patent application filed in 2020 indicating data from its devices is sent to a cloud-based servers; BrainCo’s code that allow developers to access user brain data “every half second”; and past interviews by BrainCo executives where they claim to be building the “largest database” of EEG data in the world.

What makes these findings particularly worrisome is this: Under the updated national security laws, Chinese companies are legally obligated to share their data with the Chinese Communist Party, which is partly why Congress passed a law banning TikTok.

“There is no exception anymore,” Daria Impiombato, senior analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, told Hunterbrook. “Like, it’s actually difficult to describe any Chinese company as private.”

That may be especially true of companies working in the field of BCI.

“There’s fever pitch around anything BCI,” said Tom Oxley, founder and CEO of Synchron, the American BCI company partnered with Apple, in an interview with Hunterbrook, after a recent trip to China. “The CCP has issued a top down strategic initiative.”

And while much of the conversation around BCI has focused on commercial, medical applications — such as mind-controlled prosthetics for amputees — the Chinese government has made no secret of its ambitions for other applications, including military ones.

State media discusses “super soldiers“ Translated from Chinese language text by Hunterbrook. This article cites quotes in translation from original Chinese language texts throughout. with neural enhancements. The People’s Liberation Army has hosted national BCI competitions, and its medical research arm has partnered with private companies to develop BCI products for memory and attention training for soldiers.

Three Democratic U.S. senators warned in April about the potential exploitation of sensitive neural data, saying that Chinese companies are developing “purported brain-control weaponry.”

All of this comes as U.S. President Donald Trump has escalated his attack on Harvard, pulling billions in federal funding and citing an alleged CCP footprint on campus. Since April, Trump and his allies in Congress have launched a flurry of investigations into Harvard’s ties to Chinese entities, even accusing the school of knowingly training top CCP officials.

There is no indication Harvard had knowledge of BrainCo’s ties to the CCP. The Innovation Labs hosts hundreds of companies; BrainCo spent no more than a few weeks working out of that program. And Harvard has called out BrainCo for using its name.

But Han was back on campus as recently as April to deliver remarks at the opening ceremony of the Harvard College China Forum, an undergraduate-run event drawing over 1,000 attendees.

A few blocks away, BrainCo’s former headquarters in Somerville sits mostly empty, according to three separate visits from Hunterbrook reporters, with only a few employees working at a given time.

Asked where everyone who worked at this soon-to-be unicorn went, one of the employees said only: “They are away on a trip.”

From Hype to Reality: How AI Could Supercharge Brain Tech

Brain-computer interfaces — or BCI — are, in the most simple terms, an attempt at reading minds.

More technically, BCI translates brain activity into digital signals that control external devices. In medicine, they’re being developed to restore movement and communication, to help paralyzed patients from moving robotic arms to selecting words on a screen with their mind alone.

U.S. neurotech companies like Neuralink and Synchron that are leading the field are focused on invasive applications. This involves surgically placing sensors in or on the brain to capture neural activity. Though still experimental, the technology shows extraordinary promise, offering a potential path to independence for people who have lost the ability to move or speak. (See this Wall Street Journal video explaining how Neuralink and Synchron are leading the research on BCIs to allow telepathic control of computers and wireless operation of prosthetics).

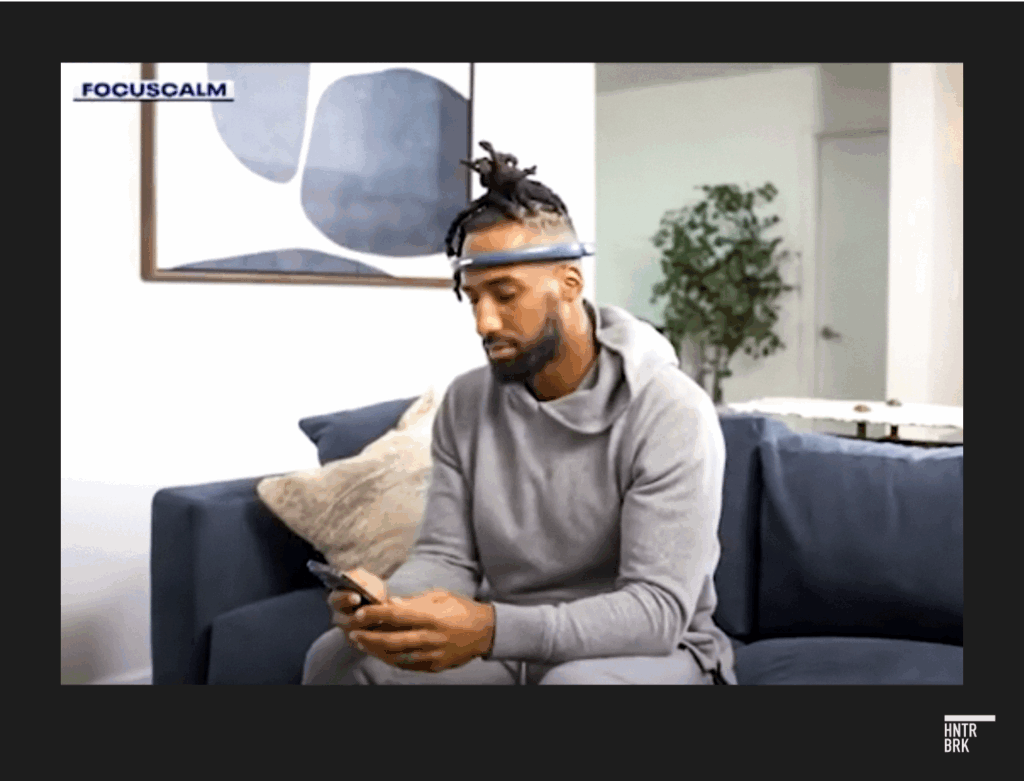

BrainCo has tried something different. Its flagship device, FocusCalm, is a noninvasive, wearable headband with EEG sensors that the company claims can collect brain wave data to help “train your brain for better focus and a calmer mind.”

EEG sensors have been around for a century. And unlike medical EEGs that use dozens of sensors, consumer devices like BrainCo’s FocusCalm use just a few. But combined with BrainCo’s AI algorithm, “inspired by NASA technologies and optimized through hundreds of thousands of iterations based on big data,” the headbands can “accurately detect electrical brain signals,” the company has claimed.

FocusCalm isn’t the only such device on the market: Similar headbands from companies like Muse claim to improve focus and relaxation, and treat anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

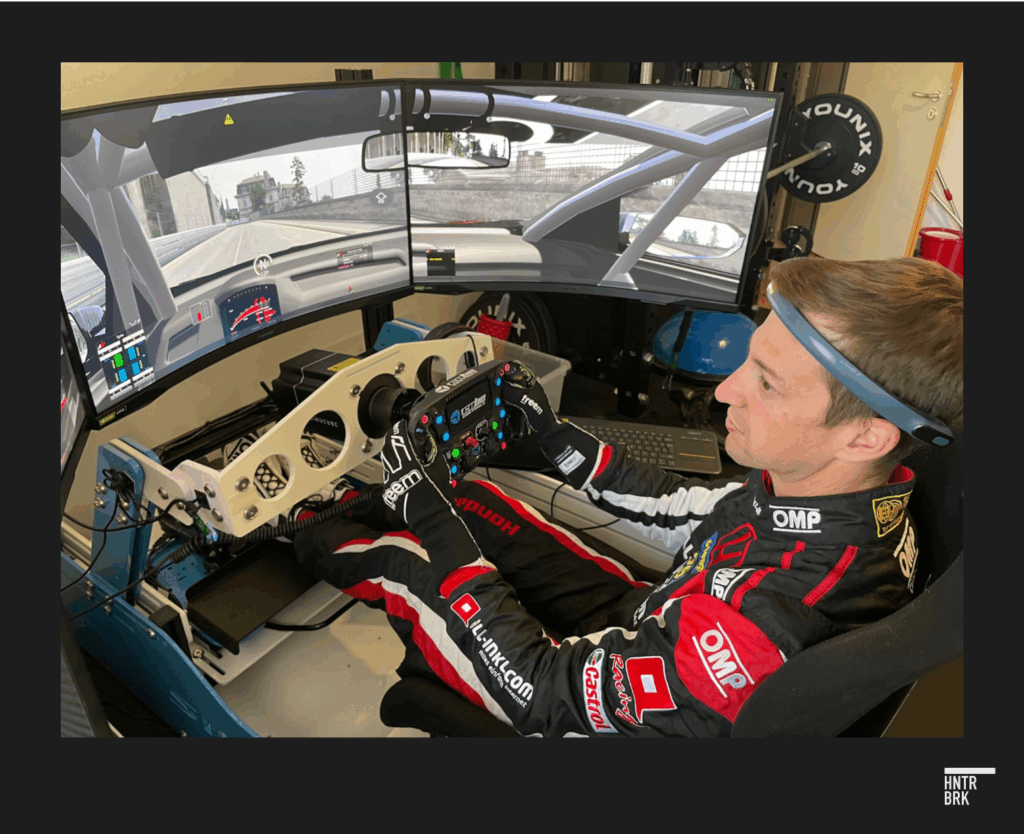

Such devices have gained traction in the sports world, as a way for elite athletes to quantify their level of focus.

Logan Ryan, a former BrainCo spokesman and NFL defensive back, explained why he was drawn to the company’s headbands in an interview with Pablo Torre Finds Out: “I realized if I could think faster, I could play faster as I got older. My legs weren’t going to get faster as a 30-year-old DB, but my mind’s a lot faster than I was when I was 20, 21. So I really started to put in a lot of mental training.”

Some scientists are skeptical about these claims, noting that unlike invasive products from companies like Neuralink and Synchron, wearable neurotech devices collect brain data through multiple layers of interference. Two neuroscientists analogized the technology to putting an ear outside the walls of a stadium — you might hear the crowd cheering, but individual conversations would be indiscernible. (This perspective mirrors a 2019 academic paper: “EEG is like hearing the roar of the crowd from outside the stadium.”)

In fact, one of BrainCo’s former executives told Hunterbrook the company wasn’t collecting much data at all — and called the idea of putting EEG sensors on someone’s head to pick up meaningful brain waves “pseudoscience-y.”

But Nita Farahany, professor of law and philosophy at the Duke University Law School, who advised President Obama on bioethics — and wrote the book The Battle for the Brain about the rise of BCI technology — warned against underestimating its power, especially in light of recent advances in artificial intelligence.

AI, she said, has started to be able to make sense of all the data that may previously have been undecipherable. “What people had labeled as noise can now be part of the signal,” she said. “Even old signals, if they were collected in raw format, could now be processed with more advanced AI techniques to start to decode more and more from what they’ve collected in the past.”

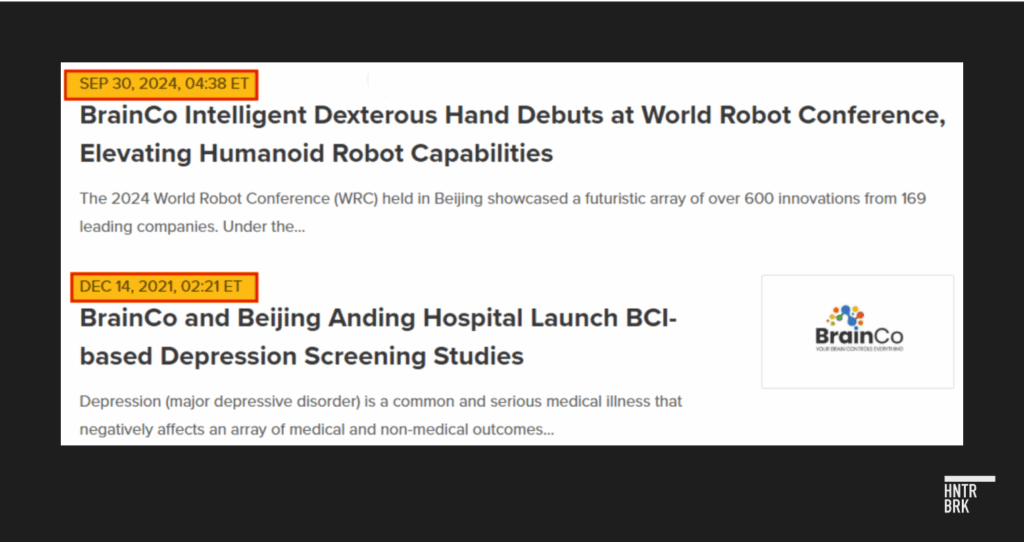

BrainCo isn’t only focused on EEG headbands. Its BrainRobotics division develops advanced prosthetic knees and hands marketed as medical devices for amputees. BrainCo also makes a version called a “dexterous hand” for integration with humanoid robots.

Instead of listening for brain waves outside the skull, the prosthetic devices read electrical signals from muscles in the residual limb (known as electromyography, or EMG). Those signals are then translated by machine-learning algorithms into fine motor control, allowing wearers to pick up a coffee cup, type on a keyboard, or even play the piano.

While EMG control is distinct from classic BCI, “it’s the same technology,” explained Han in a 2019 interview. The article appears to have been revised during the course of Hunterbrook’s investigation: It no longer contains references to the quote cited here; but the archived version (dated August 13, 2020) on the Internet Archive shows the original text that contains these references. All following references to this article will be linked to the archived version, unless otherwise noted. ”We collected brain signals and muscle nerve signals at the same time, and synchronized the signal sequences on both sides.”

The potential applications of BCI unlocked by AI could be boundless — and dangerous.

The algorithms that help athletes find their flow state can theoretically identify cognitive vulnerabilities during interrogation. The data that trains prosthetic limbs might be repurposed to teach humanoid robots to kill on the battlefield. And so on.

This dual-use potential is why both superpowers are racing to control it. Whoever has the most neural data and best algorithms could gain an unprecedented advantage in medicine, commerce, or warfare.

“You should never look at technology in isolation,” Farahany said. “China’s investment in BCI together with cognitive warfare together with humanoid robots — this is a huge play.”

Farahany sketches one possible scenario: citizens shown propaganda images while their neural responses are silently logged. Rising anger levels, suppressed reactions to Xi Jinping speeches, even the faintest hints of dissent could all be captured as data points in a state security system.

There is reason to believe that’s not just a pure hypothetical: In a chilling glimpse of the Party’s vision for BCI technology, a Chinese government-run research institute in 2022 announced a system using “AI+EEG-facial recognition” to measure Party members’ ideological commitment, according to International Defense Security & Technology Inc., a California-based defense think tank.

In a now-deleted video (but cached and reposted here), the institute claimed the “mind-reading” software could be used on party members to “further solidify their determination to be grateful to the party, listen to the party and follow the party,” according to IDST.

The post was taken down following an online outcry.

The Beginning: Building a brand on a “Harvard roots” narrative

It was 2014 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a young Chinese student named Bicheng Han arrived at Harvard, where he would soon have a vision: leading in BCI technology.

The Harvard connection opened doors.

Han launched BrainCo in 2015. In 2016, BrainCo enrolled in a 12-week program at the Innovation Labs, which by then had incubated nearly 600 other student startups. And, according to CCP newspaper China Daily, Han once taught a neuroscience course at Harvard, where he recruited students by promising “there’s a technology that enables girls to understand the minds of their boyfriends.”

The story was part myth.

Han was a teaching assistant, according to the professor who led the class.

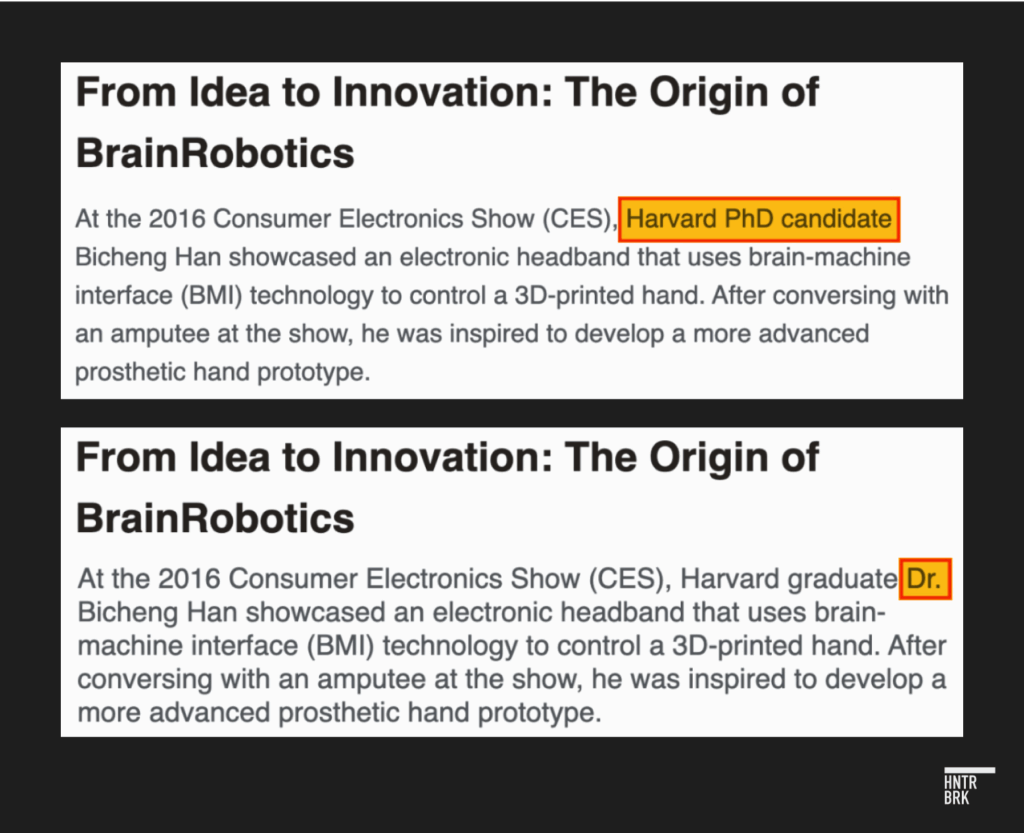

He never completed his Ph.D., despite the company referring to him as “Dr. Han” on its website.

BrainCo told Hunterbrook on September 5 that Han has “consistently been identified as a ‘PhD candidate'” and described the inaccurate reference on its website as a “single example that has since been corrected.” BrainCo deleted the reference the same day, though Hunterbrook found examples across the internet of Han being called a doctor.

Han’s claims about BrainCo’s relationship with Harvard also seem exaggerated. In a 2019 Chinese article reporting on Han’s interview with a Chinese market research firm iResearch, Han claimed that BrainCo had access to Harvard’s scientific research database — “the largest EEG database in the world.”

“BrainCo is quite special in this respect because we are a company incubated by Harvard University,” Han said.

BrainCo declined to respond to Hunterbrook’s questions regarding this, but Harvard told Hunterbrook it was “not aware of what database Han may be referring to” and “has identified no indication of access as having occurred to any such database that could have been maintained by Harvard.”

As of September 15, the article no longer contained references to the database, although an archived version on the Internet Archive does. (The revised article also omits previous information regarding BrainCo’s funding and investors, which included the CEC, a reference to BrainCo now being the company with the “largest data storage capacity in the brain interface field,” and a claim that “EEG data…cannot be transferred across borders, but models trained with this data can.”). These changes appear to have been made in the last two weeks — days after Hunterbrook contacted BrainCo with specific questions about statements in the now six-year-old article.

BrainCo also appears to have continued using Harvard’s name across communications, despite being admonished by Harvard for violating its policy that prohibits the use of Harvard trademark for commercial purposes.

A Harvard spokesperson told Hunterbrook that it “became aware of violations of Harvard’s trademark and use-of-name policies by BrainCo” in 2019 and 2020 — claiming it “engaged the company directly to ensure those violations were resolved.”

BrainCo declined to comment about its alleged misuse of Harvard’s trademarks.

Perhaps this is all more a sign of sloppiness than mendacity. It would fit the image of disorganization at the company painted by one former executive at BrainCo, who described the company as having a “severe case of ADHD,” without any specific idea of what to build, starting one project then quickly dropping it to move onto the next cool project.

But even amid the purported chaos, Han managed to assemble a team of experts from “Harvard University and MIT Brain Science Center” to join his venture.

And with its Harvard associations and American-educated scientists, BrainCo made waves with its technology.

In 2017, MIT Technology Review was celebrating Han as one of their “Innovators Under 35.” The headline: “An inventor that brings brain machine interface out of science fiction into reality.”

BrainCo also released an affordable prosthetic hand, named one of Time Magazine’s “100 Best Innovations of the Year” in 2019.

In total, BrainCo’s had amassed “more than 360 patents in the field of brain computer interface,” according to a company profile at a Chinese tech expo.

But while Han had recruited America’s brightest minds to build out the company in the U.S. — and generated praise in American media — to his Chinese audience, he made his loyalties clear:

“Starting a business now is equivalent to contributing to the development of the motherland,” Han told a China-based outlet in 2021.

The Money Arrives from China, as the Harvard facade fades

The first break came in 2017. BrainCo announced a $15 million funding round led by Decent Capital — the venture office of Tencent co-founder Jason Zeng — and China Electronics Corporation (CEC), according to a write up from the publication EdSurge.

About a year later, government emissaries from Hangzhou visited Somerville to meet with Han, Chinese media reported. “Moved by the team’s passion and dedication,” the government envoy “brought Qiangnao Technology to Hangzhou, providing the R&D and industrialization space needed for its headquarters,” the report said, referring to BrainCo’s Chinese operating arm.

In a video posted on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, Han attributed his decision to move to Hangzhou to the visit: “What really moved me was that they were willing to go such lengths to bring talent and projects back to China,” Han said. “I felt this was the best to pursue my work in brain-computer interfaces … not just to build a company, but to contribute to a national strategy and a much larger vision.”

Thus BrainCo’s Chinese headquarters was born, plump with seed money and generous support from the Hangzhou government that reportedly included tax breaks, rent subsidies, and special funding.

At the time, the significance of CEC’s name among the funders might have escaped most Americans following BrainCo. But on its own website, CEC describes itself as “one of the key state-owned conglomerates directly under the administration of central government, and the largest state-owned IT company in China.”

It is also now subject to U.S. government sanctions.

On June 3, 2021, the Department of the Treasury placed China Electronics Corporation on its inaugural list of Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies from which U.S. investors would be prohibited from purchasing securities. On January 7, 2025, the Department of Defense placed CEC on its list of “Chinese military companies operating in the United States.”

A Chinese military contractor designated by the U.S. for its role in the “PRC’s Military-Civilian Fusion strategy” was now part of the investor syndicate behind a Harvard-incubated startup.

Two years after that initial funding round, Chinese databases showed a broader line-up of state-tied investors:

- China Everbright Limited — the Hong Kong arm of China Everbright Group, a state financial conglomerate owned in part by the Ministry of Finance.

- CE Huada Technology Company Limited — a semiconductor affiliate of CEC.

- CDH Investments — one of China’s most politically connected private equity firms.

The state money didn’t stop there.

By 2024, BrainCo was raising capital directly from government funds.

The Zhejiang Provincial Industry Fund announced it had invested 200 million yuan (about $27 million) into BrainCo, while boasting that the deal had leveraged another 400 million yuan in matching “social capital.” Hangzhou Science and Technology Innovation Fund reportedly also injected two rounds of funding in 2022 and 2024, according to local media.

By this point, the facade of a quirky Cambridge startup had fallen away.

James Ryan (no relation to Logan Ryan), then dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education who became an advisor to BrainCo in 2017, stepped down in 2023, Ryan told Hunterbrook in an email. He explained he served largely as a mentor to Max Newlon, a former Harvard Graduate School of Education student who joined BrainCo in 2016 and was later promoted to president. Newlon also stepped down in 2023.

Asked about BrainCo’s links to the Chinese government, Ryan told Hunterbrook he didn’t know anything about it; and when told BrainCo had plans to IPO, Ryan said he would not exercise the options he had been granted in the company.

“I am disturbed and saddened to hear about ties to the Chinese government,” he said. “And very disappointed, obviously.”

Ryan explained that, as an administrator, he had been briefed on China’s attempts to steal intellectual property from American universities. He said he even spoke to Newlon about it. And Newlon had said, plainly: “‘We are not connected to the Chinese government.’”

“I truly hope Max didn’t know.”

Newlon did not respond to multiple requests for comments by Hunterbrook.

Another former executive at BrainCo’s Somerville office who asked to be anonymous told Hunterbrook that, by 2024, things got “really hush hush,” with rumors of the company doing “something crazy in China, a huge contract.” The source also said Han was shutting down the teams at Somerville, firing people one by one.

“It was really sad,” they recalled.

The mood couldn’t be more different in China, where BrainCo was being described as “one of the world’s best-funded neurotech companies,” as it began gearing up to IPO at a $1.3 billion valuation — along with fellow “Little Dragon” Unitree, at $7 billion. Another Little Dragon company, Manycore Tech, which makes 3D design tools using AI, filed for a Hong Kong IPO in February after dropping U.S. listing plans due to regulatory challenges faced by Chinese firms, according to TechinAsia.

From a Dystopian Test Run to Brain Training for Athletes

The scene looked like it had been ripped from an episode of Black Mirror: a classroom of primary school students, all wearing black headbands with electrodes pressed against their skulls. Their small, serious faces were captured as their brain activity was tracked and quantified.

The images were from the 2018 debut of BrainCo’s Focus EDU headbands in China that would “measure how closely students are paying attention through electrodes that detect electrical activity in kids’ brains and send the data to teachers’ computers or to a mobile app.”

The international backlash was swift.

“Virtually unobstructed access to a potential sample pool of around 200 million students” would “provide a key advantage for China in the ongoing race with the U.S. for global dominance in the field,” warned the Wall Street Journal.

Chinese social media erupted with criticism. Parents questioned whether their children had become lab rats. Privacy advocates sounded alarms. Responding to the online backlash, the local education bureau suspended the headbands a few months later.

For a while, BrainCo retreated from the public spotlight, with an almost three-year gap on PR Newswire.

But BrainCo hadn’t gone away.

Even as the classroom controversy raged, BrainCo found at least one school in the U.S. willing to test out the experiment. A Boston school gave the headsets a try in 2019, according to CBS News, though it’s unclear whether this was a one-off demonstration or an actual purchase.

BrainCo found a yet more accommodating market: elite athletes desperate for any competitive edge.

Enter Dr. Riccardo Ceccarelli, an Italian sports doctor who’d spent decades training Formula 1 drivers from his facility in Tuscany.

In 2019, searching for ways to optimize mental performance, he discovered BrainCo, noting its devices were “the best and most reliable,” he told Pablo Torre Finds Out in an interview.

He cited the application in Chinese schools as an inspiration.

“One of the first pictures that I remember about BrainCo was an application that they did in a school, in a Chinese school for babies,” he said. “You know that the problem of the babies is that they lose easily — especially the new generation — the attention, the concentration.”

“There are lots of applications, positive applications, not for punishment, but for improving,” he said.

For Ceccarelli, the application was sports — and BrainCo was happy to help.

BrainCo didn’t just sell him headbands — they provided full integration with Formula 1’s existing training apparatus. “Without their support, obviously for us, it would have been impossible to create a system like this,” Ceccarelli said.

Ceccarelli became BrainCo’s gateway to elite sports, with his name literally on the box.

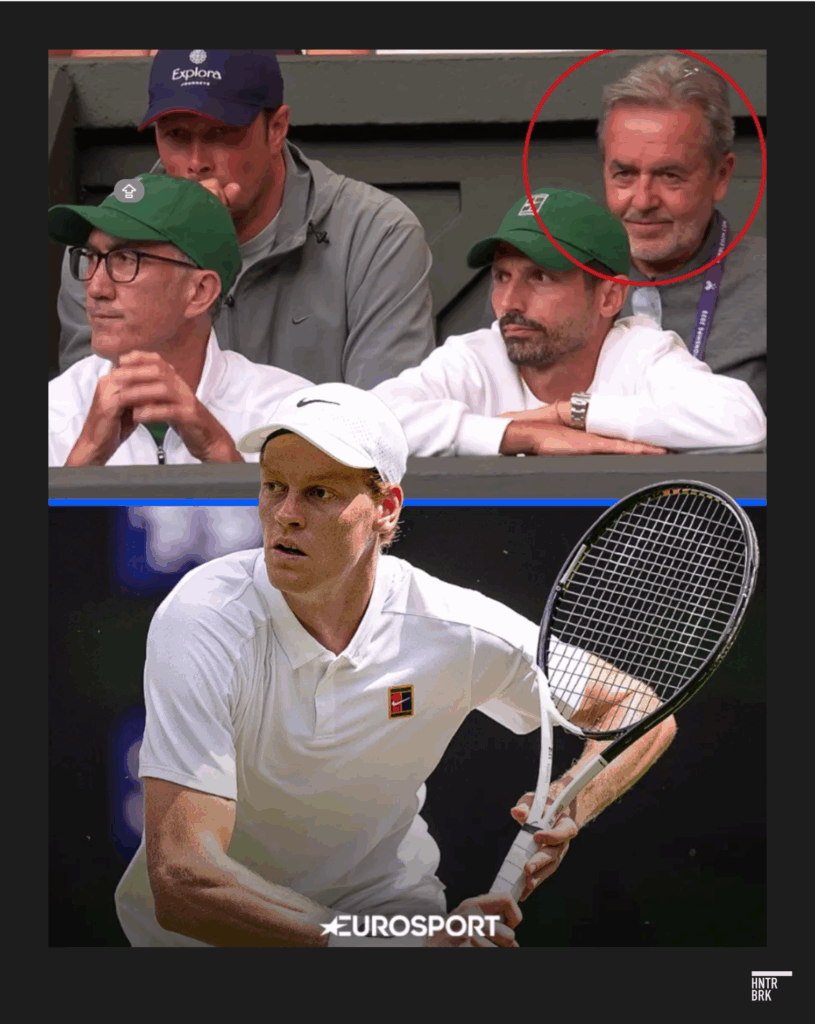

Using BrainCo’s FocusCalm, Ceccarelli said he trained athletes like Jannik Sinner to control their mental state. “Jannik had to learn how to cook,” he said, likening the gelling of Sinner’s brainwaves to “a good carbonara.”

Today, Sinner is the world’s No. 2 tennis player.

Word spread through the sports universe. According to Ceccarelli: Mikaela Shiffrin used FocusCalm, as she cemented her place as the most successful alpine skier in history. Italian Olympic teams adopted it. Manchester City players integrated it into training.

BrainCo’s website boasts its headbands are “currently used by over 20 NCAA teams and Olympic and professional organizations.” The company has also mentioned relationships with the U.S. Olympic Weightlifting Team and the U.S. Olympic Bobsledding Team.

In his interview, Ceccarelli revealed: “We are closing a contract with one of the best football teams in the world,” likely referring to soccer rather than American football. He also said he planned to bring BrainCo’s technology to the Middle East, working with governments on “aviation” and “military” applications.

Super Bowl champion Logan Ryan found BrainCo through an unexpected path: yoga.

“I would use yoga as my sense of therapy,” the NFL defensive back explained in his interview with Pablo Torre Finds Out. His instructor introduced him to breathwork, then to a device that gamified mental training. (Logan Ryan is not related to James Ryan)

“You would play a race car game. The more that you were in the right breathing and the right mental space, the faster your car would go. And the harder you tried, the slower it would go.”

The paradox fascinated him. Success came from letting go, not forcing. “I was practicing how to be in the flow state every single night. So when the two minute happened or the last drive against Tom Brady is happening, I’m not freaking out.”

The results seemed real. Ryan intercepted Tom Brady’s final pass as a Patriot. Picked off Aaron Rodgers at Lambeau Field. Got Peyton Manning too.

“I finished my quest of picking off all the GOATs of my era.”

BrainCo made him a spokesman, he said. In 2022 commercials, he endorsed the technology that helped him best the best. The company showcased the two-time Super Bowl champion who used their device to read the greatest quarterbacks in history.

Then, during an interview for this investigation, Ryan learned about the company’s apparent links to the CCP.

Torre laid it out: Chinese state funding. Sanctioned entities. Congressional warnings about “brain-control weaponry.”

Asked if he knew about any of this: “Yeah, no, absolutely not,” Ryan said. “You know, I had no idea about that.”

“Nobody on my team could even have thought this is a possibility,” he added. “That’s all pretty alarming to me and I definitely need to look into that.”

Asked if he’d use the device again, he said, “Not if my information is going to a Chinese robot, I would not.”

Though he noted, if humanoids could really train on his brain data, then they’d be “making some quick decisions, some smart decisions out there.”

“They’ll be tough to beat, man,” he joked.

Beijing’s Deepening Reach Into Private Data Comes Amid BrainCo’s Conflicting Data Protection Promises

For any BCI company, data isn’t optional — it’s the raw material that makes or breaks the technology. To build reliable models that can decode brain signals accurately, companies need large datasets of EEG, behavior, and attention metrics.

That’s what Han has said, himself.

In a 2019 interview with a Chinese market research firm iResearch, he explained that the reason BrainCo was able to achieve such a high accuracy rate in interpreting brain signals was because their model was trained from the “world’s largest EEG database.” (That database, Han claimed, had been accessible through Harvard, although Harvard denied knowledge of any such database in an email to Hunterbrook.)

After BrainCo’s Harvard links ended, BrainCo had been collecting “massive amounts” of data from its users on a large scale through our equipment to train “90% of our models,” Han said in the interview.

“In Latin America alone, we’ve collected data from over 6,000 students. Including data from China, we now have EEG data from over 50,000 people,” iResearch quoted Han as saying.

Yet, when Hunterbrook asked BrainCo about its data collection, a company spokesperson vehemently denied that BrainCo collects any user data, saying “all EEG data remains within the user’s smart device and is purged from the application at the conclusion of each use.”

The statement mirrors the privacy policy for FocusCalm — last revised on September 7, 2025, three days after BrainCo’s response to Hunterbrook — which says: “To protect user privacy, all EEG data is automatically purged from the application at the conclusion of each use.”

The revised policy explains only the computed user scores are sent to BrainCo’s servers, and that these scores “cannot be reverse-engineered to recreate raw EEG signals or any user-specific biometric data.” An earlier version of the policy saved on the Internet Archive also claims EEG data is never collected, but warns that all data other than EEG data is “collected and sent to BrainCo’s servers.”

Inconsistencies in BrainCo’s claims about data collection abound elsewhere. Asked about data security, Ceccarelli confirmed every session is uploaded to the cloud.

Asked about how he keeps this information secure, he said he would “trust BrainCo to help me with the privacy protections.”

The critical question: Could China use this data to train its own athletes?

“Yes, absolutely. Yes, absolutely. Yes.”

According to a document for software developers on BrainCo’s GitHub repository, the device collects brain wave data and sends it to the developer “every half second” — hardly consistent with BrainCo’s claim that the data does not leave the device or the app.

Hunterbrook also dug up what appears to be BrainCo’s most recent U.S. patent application. It’s for “neuro-feedback training” and specifies that information is being sent directly between the headband and cloud servers. Asked about this patent, BrainCo did not reply as of the time of publication.

And BrainCo’s data privacy policy for all its devices, still available on its original website, directly contradicts the newly revised privacy statement intended for FocusCalm users: “BrainCo’s devices and applications collect personal data” to allow BrainCo to “monitor, maintain, and improve our services.” Attention level, location, raw EEG data, gender, and time stamps of the user are included as the types of data BrainCo collects.

In that privacy statement, BrainCo asserts that “all personal data collected through, or by using, devices within the United States are stored on servers located within the United States,” although aggregated information “may be shared with BrainCo’s international network of offices as well as third parties.”

Aggregated or not, the stakes may be high for any user data that reaches BrainCo’s offices in China, where authorities can demand access. Studies have shown that anonymized data can sometimes be reverse-engineered or linked up with auxiliary datasets to re-identify individuals.

Sweeping updates to China’s national security, data privacy, and intelligence laws now mandate private citizens and entities operating in China to hand over any data deemed critical to national security to state authorities upon request.

“The thing with the national security law is that it’s very open-ended and so, under the banner of national security, they can in fact request access to any data they need,” Impiombato, the Mercator Institute senior analyst, told Hunterbrook. Impiombato recently authored a study on how BCI and other emerging behavior-shaping technologies could be harnessed for political influence and national-security purposes.

“Non-defense companies or research institutes might reach a breakthrough in something that has a military application, then that becomes classified research and can feed directly into the military industrial complex.”

This is in part why Congress passed a law banning TikTok in the U.S. While TikTok claims that it stores the data of Americans on American servers, critics have pointed out that TikTok’s parent company servers are all located in China, and company employees or Chinese government agents may have access to systems, backups, or tools that allow them to view or manage that data.

From Wellness and Education Tech to Military-Grade Robotics in the Age of Brain War

It may sound farfetched, but experts insist brain wave data may really be part of China’s recipe for the future of robotics.

Beijing’s interest in incorporating AI into warfighting capabilities is hardly unique. Countries including the U.S. have poured billions into “algorithmic warfare” initiatives, experimenting with AI-enabled battlefield decision-making, drone swarms, and predictive intelligence. Nor has Beijing downplayed it: Over the past two years, official military mouthpiece PLA Daily has published a number of articles discussing the military applications of humanoid robots, the South China Morning Post recently wrote.

What makes China unique — and potentially worrisome in the context of BrainCo, according to experts — is the increasingly blurred lines between civilian industry and the military under Beijing’s military-civil fusion strategy that seeks to leverage the civilian economy for rapid military modernization.

In other words, BrainCo’s U.S.-grown technology, as well as all of its data can flow straight into the hands of Chinese Communist Party and military authorities.

Meanwhile, BrainCo has shed its image as merely a wellness and education tech company, debuting as Beijing’s poster child for its BCI ambitions and deepening collaboration with known state-controlled entities leading China’s AI revolution.

At international trade shows, BrainCo no longer emphasizes classroom concentration. Instead, it showcases its “industrial dexterous hand” — a prosthetic originally designed for amputees, now marketed as a key component for humanoid robots. (In a comment to Hunterbrook, BrainCo claimed amputees were still its main market.)

At one tech expo in Barcelona in March, “a sci-fi scene of a ‘cyber human’” demonstrated by a Unitree robot interacting with BrainCo’s dexterous hand provoked “waves of amazement and applause,” according to one business news outlet. Unitree was recently called out by members of Congress as “a company with well-documented ties to PLA-affiliated institutions and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) entities.” Documentation from Unitree’s codebase confirms BrainCo is one of its hardware suppliers.

And then, there’s Huawei.

In 2024, BrainCo — alongside 15 other Chinese tech companies — signed a cooperation agreement to “build superior robots” with Huawei’s newly launched Global Embodied Intelligence Innovation Center, local news reported.

Huawei isn’t just any tech company. It was sanctioned by the U.S. for enabling state surveillance of religious minorities — developing facial-recognition technologies specifically designed to detect Uyghurs, a mostly-Muslim ethnic group in China’s Xinjiang province, and automatically alert government authorities.

The web of military connections runs deeper. BrainCo has reportedly also cooperated with at least three of the Seven Sons of National Defense, Chinese universities whose students are now barred from U.S. graduate programs because of their direct ties to the military establishment.

Earlier this year, BrainCo joined the government-sponsored Shijingshan Humanoid Robot Data Training Center — Beijing’s first such facility “expected to produce more than one million high-quality multi-modal data every year.” The data would be used to train the AI models that make up the robot’s “brain,” Chinese news reported.

Asked about these connections, BrainCo offered blanket denials that their technology serves any military purpose: “We have implemented stringent compliance measures that explicitly require our customers not to use or transfer our technology for prohibited end-uses or to prohibited end-users, including military applications,” a BrainCo spokesperson told Hunterbrook in an email.

But when pressed for specifics, the company went silent.

BrainCo declined to respond to Hunterbrook’s follow-up questions about ties with military contractors like Unitree and Huawei, or what concrete measures prevent its partners from sharing sensitive information with the government.

Instead, the spokesperson accused Hunterbrook of making allegations that “contain erroneous biases and numerous misrepresentations that fundamentally mischaracterize our work and mission.” They warned that “publishing it would not only severely damage your organization’s credibility and reputation, but could unfairly and unjustifiably damage our company’s reputation for which we would hold your publication responsible.” BrainCo said the report was full of “unsubstantiated speculation” and “false information.”

Notably, BrainCo’s classroom surveillance ambitions — which sparked global outrage in 2019 — have quietly resumed.

The company found a new customer in Ningxia, where BrainCo headbands, marketed as a “cognitive intervention system,” will monitor schoolchildren with “special needs,” according to a government contract obtained from the official Chinese government procurement database.

The location may be telling. Ningxia is a central Chinese province where minority Hui Muslim communities have been subjected to intense CCP “Sinicisation” campaigns — including mosque closures, surveillance, and the imprisonment of religious leaders, according to an NPR report.

For Duke’s Farahany, this represents the ultimate authoritarian toolkit.

“This seems like the most powerful kind of oppression that you could do and not have to physically harm somebody,” said Farahany. “If you’re an authoritarian government, it’s an insidious way to achieve your goals.”

The implications extend far beyond individual privacy.

As The Atlantic observed, an authoritarian state with sufficient processing power could funnel every neural signal into government databases, creating a predictive algorithm for dissent.

It’s a terrifyingly simple formula: No physical violence required. No detention centers. No interrogation rooms.

Just a headset.

AuthorS

Wendy Nardi joined Hunterbrook after working as a developmental and copy editor for academic publishers, government agencies, Fortune 500 companies, and international scholars. She has been a researcher and writer for documentary series and a regular contributor to The Boston Globe. Her other publications range from magazine features to fiction in literary journals. She has an MA in Philosophy from Columbia University and a BA in English from the University of Virginia.

Dhruv Patel is an investigative journalist based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, specializing in data-driven reporting. He helps spearhead investigative coverage at The Harvard Crimson, and his reporting has been cited and discussed by The New York Times, CNN, The Boston Globe, ABC News, and BBC, where he also frequently contributes commentary. A John Harvard Scholar at Harvard College, he studies computer science and economics to leverage machine learning for accountability journalism.

Blake Spendley joined Hunterbrook from the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), where he led investigations as a Research Specialist for the Marine Corps and US Navy. He built and owns the leading open-source intelligence (OSINT) account on X/Twitter, called @OSINTTechnical (>1 million followers), which now distributes Hunterbrook Media content. His OSINT research has been published in Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, and The Economist, among other top business outlets. He has a BA in Political Science from USC.

Alec MacDonald is a contributor to Hunterbrook Media, where he focuses on Open-Source Intelligence reporting, China, and Taiwan. He is a News Producer for TaiwanPlus News, a division of Taiwan Public Television Service in Taipei, Taiwan, where he focuses on geopolitical and domestic political stories. Previously he was a post-graduate researcher at National Dong Hwa University in Taiwan where he focused on governance, policy, and development in East Asia.

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar (taking much easier classes than Dhruv!) and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

EditorS

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.