This is the second investigation in a new Hunterbrook Media series on the poisoning of American communities.

For decades, polluters have sickened towns and cities across the country by releasing toxic chemicals, often with impunity.

Hunterbrook has built a nationwide database to expose harm to communities and ecosystems, then hold accountable those responsible.

Our latest investigation takes us to Illinois.

Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Law is in conversations with firms regarding potential litigation on behalf of victims. Hunterbrook is also sharing its findings with the Illinois EPA and other regulatory agencies with oversight over Viscofan’s Illinois facility.

Alan Johnson spent more than 43 years working inside a chemical plant — a job that paid the bills, gave him purpose, and may have been slowly killing him all along.

Now 73, he lives about 15 miles outside Danville, Illinois, in a low-slung house with algae-streaked siding and a red barn out back. Inside, the rooms are dim and close. Model cars line the shelves. Pill bottles cluster on the table. Two dogs drift through the tight home — one calm, the other, Oreo, white-haired and rambunctious, eager to sit at Johnson’s feet.

It was raining the day we met. We’d planned to sit out front but instead settled in his living room, where a walker stood beside a worn recliner, and the window looked out onto wet grass. His hands shook and his voice wavered at times. The words came in fits and starts.

Parkinson’s, he said. Heart disease. Three kinds of dementia.

“You can’t hardly get a breath in there,” Johnson said, describing the air inside the chemical plant. He explained, “Even if you take a shower, you still got it on your skin.”

He spent decades working around vats of chemicals at the Danville factory now owned by Viscofan ($VIS.MC), the world’s largest producer of artificial meat casings. The plant emits carbon disulfide, hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and other chemicals — all substances linked to neurological, respiratory, and cardiovascular harm.

He remembers the burn pits behind the building — how they’d torch waste before dumping the rest under what’s now a maintenance shed. He remembers red-tinted runoff in the creek out back and dead fish. He remembers Environmental Protection Agency officials showing up in the middle of the night and giving his boss 20 minutes to shut down a leak — or they’d shut the whole place down themselves.

The problems, he said, never really stopped. “They don’t want to fix it. It costs money.”

His wife never worked a day at the plant, but died from a bad heart. To this day, Johnson thinks he brought toxic chemicals home on his skin.

And he’s not alone.

Hunterbrook Media talked to more than 40 Danville locals and former Viscofan workers — some of whom were granted anonymity out of fear of retaliation — to gather firsthand accounts of the experience of living next to one of Illinois’ most problematic polluters. Many told the same story: a workforce scarred with an unusual number of health problems, a sick town, and a company that never seemed to answer for any of it.

Some said employees were paid off in exchange for silence. Some residents only posted anonymously online. Others wouldn’t speak at all.

Still, the stories surface.

The roof caving overhead. Pennies turning green in one worker’s pockets. An employee being told to take a taxi, instead of an ambulance, to the hospital after coming into contact with acid. Lick Creek, where some locals recall swimming as children, carrying trails of dead fish. Locals call it “the smell.” It’s sharp, metallic — like cat pee and rotten eggs. Some say it causes headaches. Others don’t notice it anymore. It’s just part of living in Danville.

Before Viscofan, the plant had been owned by an American company, Teepak — and was, workers say, better run and safer.

“Teepak, they took care of their employees, they took care of us,” Johnson said. “This place? I don’t think they even give hams anymore for Christmas.”

Viscofan, a Spain-based multinational that touts Danville as its largest plant in the United States, took over the plant in 2006. Locals say that’s when things got worse. Enforcement didn’t improve, and protections weakened. And the illnesses? They kept coming.

Since then, the company has repeatedly violated environmental law through uncontrolled emissions, routine discharges into local waterways, and mishandling toxic waste on its property, according to public records obtained by Hunterbrook. For years, Viscofan defused pressure from the Illinois EPA by signing compliance commitment agreements — at least five since 2015.

But in June, that familiar escape route collapsed. In a sharply worded letter to Viscofan’s U.S. leadership obtained by Hunterbrook via a public records request, the Illinois EPA signaled its intent to pursue legal action, arguing that the company’s latest proposed settlement was insufficient given the “nature and seriousness” of the violations.

And now, as sickness spreads and more names fill the obituary pages, Danville’s residents are left asking: Why is this plant still here?

The Factory Town

Danville’s past reads like a tale of Midwestern industrial glory. A city powered by factories, the kind of place where stable, well-paying jobs were plentiful and manufacturing was booming. General Electric, Chuckles, Bunge, and Heatcraft were there, along with a Hyster forklift plant, and a large General Motors foundry that employed thousands.

But like so many factory towns in the Midwest, Danville watched its economy drain out in slow motion as plants closed and people left. Since 1970, Danville has lost at least six manufacturers and more than a third of its population.

What followed is still playing out. Today, Danville’s violent crime rate is nearly 1,700 per 100,000 people — among the highest in Illinois. The headlines barely scratch the surface: a man stabbed in an alley behind a neighborhood gas station and another slashed in the neck. Vacant homes — long abandoned — go up in flames, sometimes several in a single week, each blaze engulfing more than crumbling boards. The city is stretched thin, and trust in public systems is largely gone.

One side of town, where Danville High School is located, still bears the bones of what it was — the other side wears what it’s become. Viscofan straddles that intersection.

The factory was built in 1957 by Teepak, then a U.S.-based meat casing company that supplied major meat processors with cellulose and fibrous film. For decades, Teepak was seen as a reliable employer that treated workers well. In 2006, the company was purchased by Viscofan. Danville became its flagship U.S. facility; as of 2023, the plant employed nearly 300 people. And today, the site sits on more than 2.3 million square feet of land and operates around the clock, according to the company. The Danville facility is seemingly the only Viscofan plant in the U.S. producing cellulose casing fibrings. Its facility in Montgomery, Alabama, converts “cellulose, fibrous, and plastics,” and its Bridgewater, New Jersey, plant focuses on collagen casings, according to the company’s website.

Other manufacturers still operate in Danville — including Mervis, Hyster‑Yale, Thyssenkrupp, and Flex‑N‑Gate — but among the locals Hunterbrook spoke with, there was a near-unanimous view that Viscofan stands apart, and not in a good way.

“My mother worked for Bunge for years, and she never had issues with that place,” said Amanda Brady, a former Viscofan employee. “Hyster is just a place that ships parts — no fumes at all. Viscofan is the worst place I have ever worked. I didn’t mind the job itself, but the environment was horrible and was getting worse by the day.”

Where the plant is located tells its own story.

Viscofan backs up against some of the most distressed housing in Vermilion County. Fair Oaks, a nearly 200-unit public housing complex, sits a little over half a mile away. When a Hunterbrook reporter visited the complex in July, the neglect was evident — worn brick buildings with rusting window frames in need of repair.

Some of the homes in the streets just behind the plant echo the same pattern: overgrown lawns, dirty siding, personal belongings, even a refrigerator, catching dust on porches. Within a one-mile radius of Viscofan, 64% of residents are low-income, and around 25% of households earn under $15,000 a year.

A Hunterbrook analysis of property data shows that many of the cheapest homes in Danville cluster tightly around the Viscofan plant. Properties within half a mile sell for a median of just $47,500, and home values remain depressed out to nearly two miles.

Beyond that ring, values climb steeply. By three miles, the median home price has nearly doubled to $68,000, reaching about $90,000 by five miles. At the 10-mile mark, the median reaches $109,000 — more than twice as high as homes closest to the smokestacks.

The disparity holds even after adjusting for home size. Within two miles, the median home price is about $35 to $40 per square foot, compared to over $72 per square foot 10 miles out. Lot sizes also expand steadily: a median of 7,000 square feet near the plant, versus more than 11,000 square feet about 10 miles out.

In short, Viscofan’s footprint doesn’t just happen to sit amid low property values — it defines a gradient of cheaper and smaller housing radiating outward from the plant.

Still, some lash out at the critics. “Complaining about a smell, then complain when they close down, and folks are out of work as local industry further dive bombs,” one resident wrote in a comment on Facebook. “It’s not a perfect world.”

In Danville, that kind of tension is just another part of the landscape. Viscofan is still here — and that’s either the problem or the point.

Sick and Spreading

“If you made it out,” said Damian Street, a former Viscofan employee, “you were going to die in six months.”

“If you made it out, you were going to die in six months.”

Damian Street, Viscofan former employee

Street worked at the plant for nearly seven years, first as a process technician. He’d grown up just blocks from the plant, back when it was still Teepak, and said his grandfather had retired from the quality lab there. But by the time he started in 2016, the stories he’d heard as a kid — about the air, the chemicals, the people getting sick — were no longer rumors. They were realities he was starting to see up close, every day.

“There’s been numerous people out there get cancer last few years, and I’m worried myself about it now,” he said. “I had a neighbor that used to work there. … He made it about a year before he died. It was so aggressive that there was nothing that could be done.”

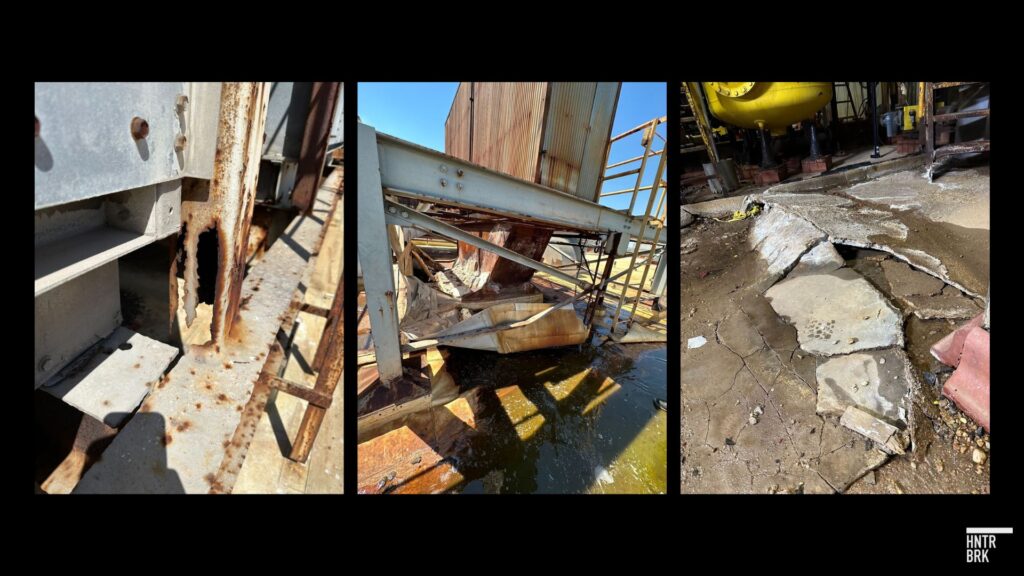

The longer Street stayed, the more it felt like the place was eating people alive. He spoke of toxic salt dumped straight onto the ground, walls dissolving under acid leaks, metal beams crumbling to flakes in months. “I’ve seen this stuff eat like complete metal,” he said. “If it’s doing that to concrete and cinder blocks and I-beams, what do you think it’s doing to your actual body?”

Over time, his colleagues started to disappear.

“It’s like two or three people have died since I’ve left from out there that have gotten cancer and died,” he said. “The EPA comes out there — they [Viscofan] make it look pretty, they do what they got to do to get by, and then they go right back to square one.”

Street’s stories weren’t an outlier. In fact, they fit into a pattern Hunterbrook began to uncover after four months of interviews, records searches, and outreach.

Hunterbrook reached out to hundreds of former workers at Viscofan’s Danville plant. Dozens responded, and nearly 20 agreed to speak. Several said they were currently battling cancer, breathing issues, Parkinson’s disease, or another severe health condition, or had recently recovered. The others pointed to friends and coworkers who hadn’t been so lucky. Through interviews, Hunterbrook learned of at least 20 former employees at the Danville plant who had developed serious health issues.

Most had cancer, but there were also reports of neurological disease and cardiovascular damage. Several also reported dental issues after leaving the plant. Brandy Lake, a former lab employee, experienced issues with her teeth and gums. In total, Brady lost 20 teeth following her time at the plant.

To understand how that could happen, we had to understand what working inside Viscofan actually meant.

Employees said that Viscofan prohibits them — but not supervisors — from bringing mobile devices into the plant. Johnny Gonzalez, a former Viscofan worker, recounted being told by his supervisors that the company was wary of trade secrets being leaked to competitors if pictures were taken.

But nearly 80 photos and videos obtained by Hunterbrook — shared by former employees willing to break company rules to expose the inner workings of the factory — reveal a grim portrait of life in and around the plant.

Inside the Plant

Viscofan is where your hot dog casing comes from — and where workers say the roof crumbles above your head and the walls are eaten away by salt.

Viscofan’s Danville plant manufactures cellulose sausage casings — transparent, high-gloss membranes used to hold hot dogs, ham sausages, and lunch meats. The product is simple. The process to make it is not.

The Danville plant uses the viscose process, a multistage chemical operation involving wood pulp, carbon disulfide, caustic soda, and sulfuric acid. In general, the sequence is controlled: Pulp is steeped in sodium hydroxide, aged, and reacted with carbon disulfide to create sodium cellulose xanthate. That compound is dissolved into viscose — a thick orange liquid — which is extruded into tubes and passed through regenerating acid baths made from sulfuric acid, which results in sodium sulfate. The cellulose is then regenerated into solid casings that are then dried and rolled into reels.

Robert Rust, a retired Iowa State University meat science professor who previously consulted for Teepak, said that this process isn’t unique to Viscofan. “I think that was the only process … for manufacturing those types of cases,” Rust said, noting that just a few companies have ever done it at scale in the United States — namely Viscofan and its competitor, Viskase. He described the market as “a classic oligopoly,” where the basic viscose formula and sulfuric acid bath have been standard for decades.

But standard doesn’t mean safe. The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies strong inorganic acid mists containing sulfuric acid as Group 1 — carcinogenic to humans — with greater risk in hot, poorly ventilated operations. At Viscofan, former workers said, dangerous exposure is normal.

The consequences could be immediate. Brady recalled a man being sprayed with 93% sulfuric acid — a concentration that can easily cause chemical burns and be corrosive to steel. Instead of calling an ambulance, the safety manager at the site made him wait while they summoned a taxi, Brady said.

Sulfuric acid, in particular, is no trivial chemical in the plant. In 2023, the Danville plant used about 6,700 tons of sulfuric acid, and at any given moment, it maintains two 65,940-gallon tanks of 93% sulfuric acid on-site, according to an Illinois EPA inspection report reviewed by Hunterbrook.

On the floor, it was seen as proof of how even life-threatening emergencies were treated as routine inconveniences inside the plant.

“They would put you under the shower station and if you felt fine after, they tell you to get a set of dry clothes and then get back to work,” one former worker said about acid exposure incidents at the plant.

When the viscose process is run cleanly, emissions are largely contained by scrubbers and solvent recovery systems. At Viscofan, it’s not.

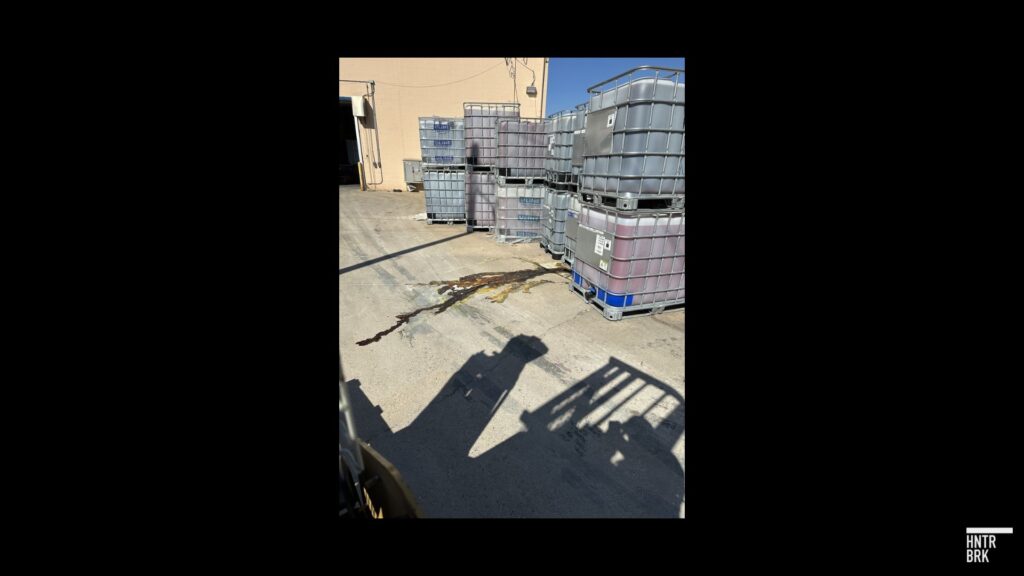

The issues begin before production even starts. Trains bring in tankers of bulk chemicals — namely sulfuric acid — via a side rail that runs directly into the plant. According to photos obtained by Hunterbrook, the ground near the unloading lines is damp with runoff and ripe with dark liquid pooling between the tracks. The liquid, which former employees say is full of chemicals, seeps into gravel and concrete. In at least one instance, the chemical-stained ground was covered by wooden pallets.

Once inside the facility, the breakdowns escalate. Carbon disulfide and hydrogen sulfide — both toxic, flammable gases — are generated during the extrusion phase, where viscose is shaped into its final form. And while the majority of hydrogen sulfide is removed through caustic scrubbers, carbon disulfide is not.

Photos obtained by Hunterbrook show hydrogen sulfide concentrations of 10.7 parts per million on a fixed wall monitor, and up to 40 ppm on a handheld reader inside the plant.

For reference, exposure to just 2 to 5 ppm can cause headaches and nausea. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends no more than 10 ppm of exposure in any 10-minute period, and OSHA sets a ceiling at 20 ppm over an eight-hour window for plants like Viscofan. Brady, the former lab employee, described Viscofan’s heightened levels as a regular occurence, and said evacuations happened roughly three times a year.

According to former workers, some areas of the plant are badly eroded, and rust and cracks in the concrete on the plant floor are common sights. “The ground under the acid tanks is eroded enough to park cars there,” said a person with knowledge of the plant’s operations.

In one picture obtained by Hunterbrook, a large concrete tank marked as “25% CAUSTIC” outside the plant showed significant cracks at its base with liquid seeping through.

Extrusion was especially bad, said Gonzalez, who said he worked at the plant from 2014 to 2016. The area was hot, humid, windowless, and almost pitch-black, and the ventilation was bad, he recalled. Giant rolls of paper were fed into dies, coated with viscose, and run through a series of acid tanks and rollers. When the casing broke, workers had to reach shoulder-deep into chemical baths, their clothes and skin soaked, according to Gonzalez. He said masks were communal, tethered to short air hoses, and often useless for the reach the job required.

“I would like, wake up feeling like I couldn’t breathe,” he recalled. “It felt like something was inside there, clogging it up.”

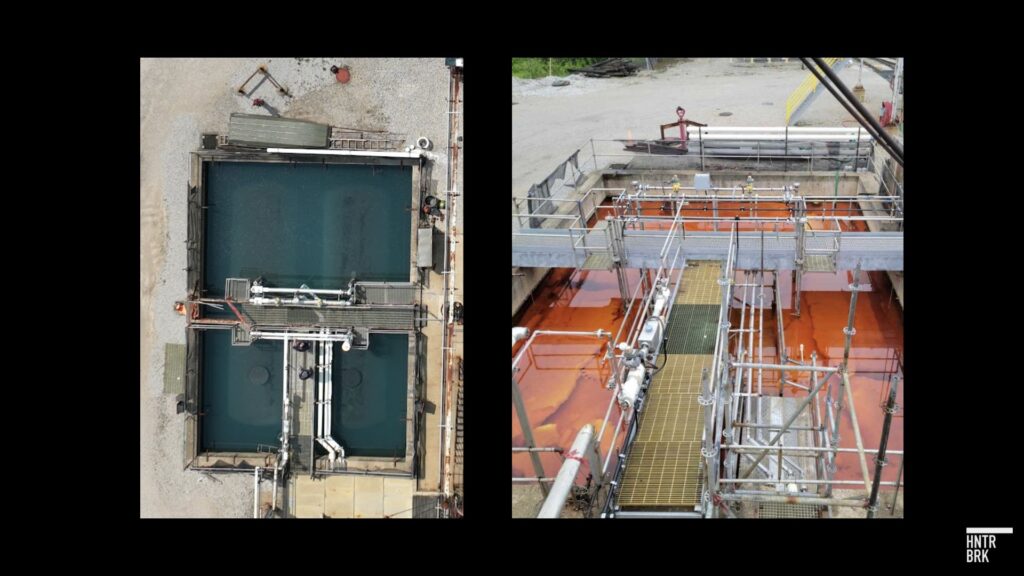

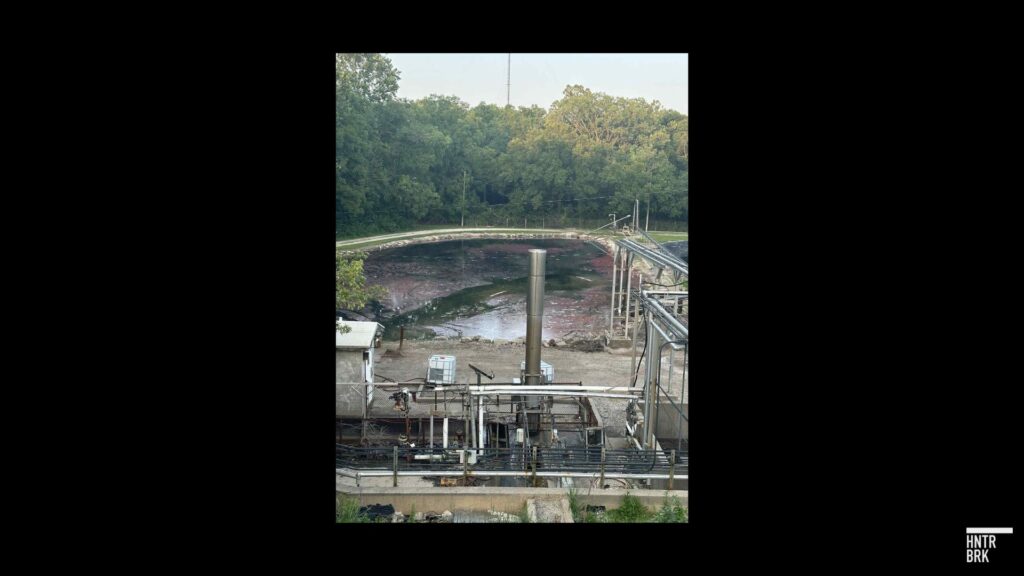

Outside the building, things don’t improve. Behind the plant are two wastewater basins known as the lagoons. In a 2023 report from the Illinois EPA, an inspector reported that the first of these, the north lagoon, received caustic material from 250-gallon totes of viscose for treatment. The second, the south lagoon, has an outfall that leads directly into the publicly owned treatment works. After the chemical waste is treated, workers routinely dredge the sludge from the lagoons for removal, according to a former employee.

“I couldn’t tell you how many animals have went across there and probably have just become part of whatever the hell is in the bottom of that lake,” said one former employee. That same employee was diagnosed with cancer within six months after leaving Viscofan.

A Record of Excess

Viscofan’s Danville plant has violated the Clean Air Act in seven of the last 12 quarters, according to the EPA. Each of those quarters included a violation marked as “high-priority” — one of the agency’s most serious categories, reserved for violations most likely to significantly harm human health and local environments or threaten the act’s programs.

And yet, the plant continues to operate at full tilt — treating less of its emitted gases on average and releasing carbon disulfide on a scale unmatched by any other casing facility in the country, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis.

In 2023, Viscofan’s Danville plant reported releasing 2.4 million pounds of carbon disulfide into the air. By comparison, the second-largest emitter in the country — Viskase’s Loudon, Tennessee, plant — reported less than 2 million pounds, with no significant violations of the Clean Air Act.

Carbon disulfide is a neurotoxin linked to memory impairment, peripheral neuropathy, and cardiovascular damage. Viscofan’s Danville plant emits an average of nearly 7,000 pounds per day, and a 2019 report from an independent research institute did not note the use of flares or biofilters — even though the Illinois EPA found in 2008 that biofiltration would be possible at the site. In filings with the EPA, the company has argued that carbon disulfide is “required to get cellulose completely into solution” — and warned that “product quality may decline” if it is compelled to reduce it.

Despite a 47% decline in emissions of hydrogen sulfide between 2012 and 2019, levels have since picked up and grown 45%. The plant’s RSEI Hazard score — an EPA measure of toxic exposure — is more than 3,300 times higher than the median among other unlaminated plastics shaping facilities nationwide.

Ammonia is another recurring pollutant. In 2014, Viscofan’s Danville plant reported releasing nearly 339,000 pounds. That number was over 145,000 pounds in 2023 — still high relative to most other casing plants. The company has stated that “reducing the amount used may impact quality and yield.”

Hydrogen sulfide, another toxic gas produced during cellulose conversion, is largely removed by a caustic scrubber, but some is still emitted. According to a report from the Illinois EPA, Viscofan is allowed to release up to 15 pounds per hour — which amounts to tens of thousands of pounds annually.

Solid waste has triggered red flags, too. Street recalled issues at the landfill about five years ago after unwashed casing waste was dumped without proper treatment. “These guys were dumping this casing right into the tote, taking it right to the dumpster,” he said. “Well, this stuff reacts with certain temperatures, so they were having flare-ups.”

He also said the company routinely ran defective machinery that produced unusable product — adding more chemical-laced scrap to the load. “They will run junk all day long,” Street said, “instead of shutting the machine down and trying to fix it.”

One man — who said he used to haul Viscofan’s waste for trash collection company Republic Services — said he witnessed the disposal operation firsthand.

“I saw it with my own eyes,” he told Hunterbrook.

He estimated he’d removed waste from about three 20-yard dumpsters of chemical sludge, three salt-filled 10-yard dumpsters, and compacted trash on a near-daily basis, including most weekends. A photo taken on Viscofan’s property obtained by Hunterbrook shows one such 20-yard dumpster lined with black plastic and stacked with yellow-orange blocks of solid chemical residue, according to the worker. The gelatinous blocks, he explained, are known as “solidified viscose” — the juices squeezed out of meat casings, collected in mini bulk tanks, left to harden, and then dumped once solid.

“It was so bad it rotted the dumpsters out on the bottom,” he said.

But he isn’t the only one who has had issues with the waste generated at Viscofan’s Danville plant. So has the Illinois EPA.

Viscofan produces three major types of solid waste: sodium hydroxide solution, a byproduct of the viscose process; xanthate crumb, the byproduct of the reaction between carbon disulfide and cellulose; and viscose that didn’t meet manufacturing standards.

In 2015, the company officially crossed the line into being “a large quantity generator” of hazardous waste after it produced more than 1,000 kilograms of corrosive sodium hydroxide in a month, according to an Illinois EPA report. By the following year, it also generated over 1,000 kilograms of flammable solids containing carbon disulfide in one month. That classification carried strict obligations: Label every container, store it properly, and ship it off-site within 90 days.

Viscofan did almost none of it, according to records from an inspection by the Illinois EPA on August 10, 2023, after it received a complaint.

On that day, the inspection report indicates, Britney Rutherford, an inspector from the Illinois EPA, asked Alvaro Mendoza, a company representative, how many totes of waste were present in different areas of the plant. He stated that there were approximately 350 totes in total. But when she walked the yard herself, the scale was much greater.

According to the report, Rutherford found more than 1,300 250-gallon totes scattered across Viscofan’s sprawling campus in Danville. Of those totes, some were dated back to 2021; one carried two different dates, marked in 2022 and again in 2023; and some even leaked caustic solution directly onto the ground.

Rutherford asked Mendoza to explain the sheer volume of waste on-site — but instead of acknowledging the backlog, in English he downplayed the problem, according to the report. In Spanish, though, Mendoza told someone that the inspector had exaggerated the count — despite photographs showing row after row of totes scattered across the yard.

“Viscofan is operating an unpermitted hazardous waste landfill,” Rutherford wrote in her report of the site inspection. “Dumping or allowing the continued spills of corrosive wastes onto the ground near the pond constitutes an unpermitted hazardous waste landfill without any of the engineering requirements of an actual landfill.”

The inspection notes also revealed a more systemic failure: Viscofan was misclassifying its waste. Instead of labeling viscose waste when it was first collected, the company waited until it aged and separated. At that point, the sodium hydroxide solution, the harmful part, had already been decanted, and the determination was made only afterward, leading to a misclassification of the hazardous waste.

The company’s own record contradicted that practice. Its contingency plan from November 19 and prior waste shipments to a disposal firm explicitly characterized the viscose solution as corrosive hazardous waste, according to the report. Yet when asked to label totes accordingly, employees apparently marked them as nonhazardous. When regulators requested a proper waste profile three times, Viscofan twice sent profiles only for the solids that had been treated, not for the liquid layer or the untreated waste as it was actually generated, according to the report. Only when Illinois EPA staff arrived on site to take their own samples did the company finally provide a complete profile. It confirmed what was already clear: The viscose solution was a corrosive hazardous waste.

By the end of that inspection, Rutherford was convinced that Viscofan was cutting corners in its waste management process — and slapped the company with 21 violations. She noted that properly disposing of all the discarded and off-spec viscose would cost the company over $700,000.

The violations set off a chain of escalating consequences. On October 30, 2023, the Illinois EPA issued a formal notice of violation. Viscofan delivered its first response on December 18, and barely a month later, on January 18, 2024, company officials were called into a meeting with state regulators to account for what inspectors had found. In that meeting, the plant claimed that the amount of waste Rutherford found was “atypical” — and blamed it on Republic Services, claiming the local trash hauler refused to accept the solidified waste.

By February 8, 2024, Viscofan tried to bargain with a compliance plan — but regulators weren’t buying it. Just a week later, the Illinois EPA warned the matter was so serious it might be handed off to prosecutors. That warning hung over the plant for more than a year, until on June 24, the Illinois EPA made its move: a letter of intent to pursue legal action.

And that is not the only legal problem facing Viscofan. In October 2024, the Illinois EPA referred two different violations to the U.S. EPA for use in separate federal enforcement actions regarding the company’s operations in Danville, according to a spokesperson for the state agency.

One involves a 2023 enforcement action over repeated air permit and emissions reporting violations dating back several years, including failures to properly monitor, test, and document sulfur compound emissions. The other, a 2021 case, centers on emissions-related compliance issues, including alleged lapses in maintenance, recordkeeping, and incident reporting.

The Locals

The harmful impacts of Viscofan’s operations don’t end at the factory’s fence line.

Before process gases are released into the air, Viscofan is required to clean them using a scrubber system — a device that brings polluted air into contact with a liquid to absorb or neutralize contaminants. When functioning properly, a scrubber can remove the vast majority of harmful emissions.

At the Danville plant, however, that isn’t always happening.

According to a picture obtained by Hunterbrook and a person familiar with the plant, stacks fans in one part of the plant — which vent gases from the extrusion process — appeared to be disconnected from the scrubber system responsible for removing harmful emissions. The elbows that would normally connect the fans to the scrubbers are missing, the person said, allowing fumes to vent directly into the atmosphere — unchecked.

Viscofan has been accused of skimping on proper air scrubber practices several times before. In 2015 and 2021, the Illinois EPA issued air-related violations to the plant, alleging that it emitted hydrogen sulfide beyond limit — and that its scrubbers underperformed in controlling toxic releases. In both cases, Viscofan struck compliance commitment agreements, promising better emissions control.

But drone footage of Viscofan taken by Hunterbrook on August 19 suggests that incidents of that kind are not relegated to the past. The video shows at least one stack fan visibly disconnected from its air scrubber, parts of which appear to be scattered across the terrace. The footage also captured the fan venting at the same time — releasing fumes into the air.

Similarly, in an aerial shot taken by Indy Drone Video, an Indiana-based videography group, in June 2023, one of Viscofan’s scrubbers again appears to be inactive — except this time the opposite stack fan is venting freely into the air.

Those same stacks, one person familiar with the plant said, contain equipment meant to measure emissions in parts per million. Federal and state guidelines limit how much can be released.

It is unclear what chemicals could be released from the particular stack vents that Hunterbrook identified as lacking proper scrubber control. An air test conducted independently by Hunterbrook just outside Viscofan’s entrance detected acetonitrile — a colorless, flammable solvent used in industrial processes, including plastics and pharmaceuticals production. It’s also used regularly in the process of casting and molding plastics.

According to the EPA, chronic inhalation of acetonitrile could result in “cyanide poisoning from metabolic release of cyanide after absorption.” The agency also notes that inhalation can affect the central nervous system and result in “headaches, numbness, and tremor.”

Chemicals released by Viscofan present a dual risk in Danville: They can travel through the air via smokestack emissions or leaks, and they can seep into water systems — most notably Lick Creek, a slow-moving waterway behind Viscofan’s industrial wastewater lagoons.

These open-air lagoons are used to store and treat runoff from the plant, located just feet from the creek’s edge. Contaminants from the lagoons can leach into the water table, flow downstream, or evaporate into the surrounding air.

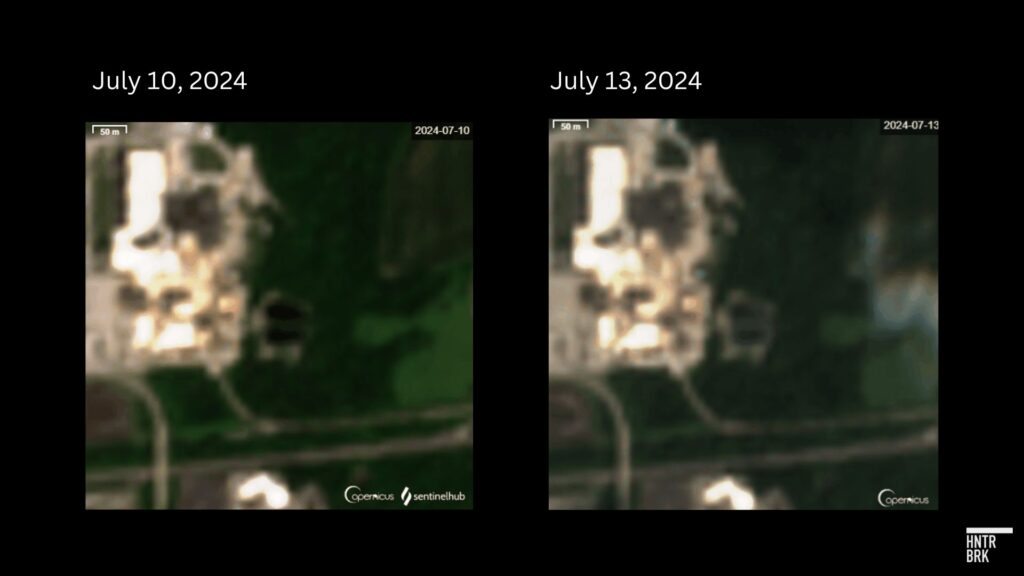

One clear example of this vulnerability occurred last year. On July 10, 2024, Danville received about 4 inches of rainfall — enough to noticeably raise the levels of the lagoons behind the plant relative to levels seen just three days later. With close proximity to Lick Creek, that kind of surge increases the risk of overflow, runoff, and contamination.

The August 19 drone footage shows the lagoon ending just a few feet from the creek’s bank.

In 2013, the Illinois EPA issued a permit for Viscofan’s Danville plant covering discharges to Lick Creek and setting pH and other limits. But Viscofan has repeatedly violated that agreement over the past decade.

The plant operates three outfalls, each discharging into Lick Creek. Since 2014, it has released high-pH and chemically contaminated water into the creek at least 20 times, according to records reviewed by Hunterbrook. Among the chemicals in these incidents: Red Dye 40, a sodium hydroxide solution, and scrubber liquid all flowing into the creek without control because of worker mistakes, poor manufacturing procedures, or aging equipment.

And at times, the contamination has been serious enough to trigger action from the Illinois EPA. In 2015, 2017, and 2018, Viscofan was cited for violating the Illinois Environmental Protection Act in connection with discharges — or conditions that could cause discharges — affecting local waterways.

When a Hunterbrook reporter visited the creek, the smell was sharp and unmistakable — a chemical musk hanging over the water.

Some residents who live near Lick Creek have echoed these concerns online. “They also dump the chemicals in water behind them,” wrote a local, whose home borders the creek. “I live on Daisy Lane by there — dead fish all the time.” Another resident replied, “I was told the same thing.”

In Danville, symptoms tied to chemical exposure aren’t theoretical. They’re routine.

“I’ve been back in Danville now for about 10 years,” said Sheena Morris. “I was born and raised here.” She’s been working full-time at a print shop less than a mile from Viscofan for more than three years now.

“There’s always a smell,” she said. “It gets really bad a couple to three times a week. Sometimes it’s like rotten eggs, like a sulfur smell to it … like a boiling hot dog.”

Her father, Tom Kelly, who owns the shop, has cancer — several types. So did her fiancé, who died last September. Two employees have been diagnosed — one with breast cancer twice, another with skin cancer. Her grandmother died of cancer. “I know a lot more people that have it really at this point in my life than don’t,” she said.

Cases of bottled water were stacked in the entryway and back rooms of Morris’ ink shop when a Hunterbrook reporter visited. Some locals don’t drink from the tap.

“We just don’t trust it,” Morris said. “I smell just a bunch of chlorine. They’re constantly treating it and then sending out notices about that too.”

When asked about the community response, she was blunt: “Nobody does really anything about that.”

“It employs people. So they’re not pushing back because they need the jobs in this community,” she added.

The health impacts she described are echoed in public data. Between 2018 and 2022, Danville’s 61832 zip code recorded 1,196 cancer cases — an annual rate of about 700 per 100,000 people. That’s far above the Illinois state average of 561.

And while there is no direct proof of a causal connection between the chemicals emitted by the factory and the health outcomes in the surrounding areas, community sentiment certainly lays some blame at Viscofan’s feet.

“My dad worked there when I was a kid,” wrote a local on a community Facebook page. “He would come home in the morning after working 3rd and the Pennie’s in his pocket would be green. … Place is nasty.”

“Came home smelling like cat pee,” another local recalled of her boyfriend who worked at the plant. “Some there have to wear mask[s]. It’s bad for the workers and environment.”

A local who said they worked at Viscofan recalled the factory removing its smokestack and facing repeated fines: “If there not burning off the chemicals I don’t see why the people living in the area can’t sue them.”

One woman said her father died of cancer after working at the plant. Another person said he knew multiple workers who died of heart attacks in their 40s. One local called Danville the “cess pool of the country.” Others described the plant as toxic and explosive: “It can even lead to infertility in women.”

Don’t Talk, Don’t Ask

Street started working in maintenance at Viscofan in 2016. At first, he liked it. “I thought, ‘Man, this is great,’” he said. “Days off, swing shift, rotating shift — what I wanted to do.”

But over time, the problems piled up. He said proper safety precautions often weren’t followed, and workers handled a slew of toxic chemicals without proper respiratory protection. “I had to take breaths, had to get down from where I was at before I lost my breath and actually passed out,” he said.

He also recalled a serious injury. “That one girl got her arm stuck in the roller,” Street said. “It literally rolled her arm for, like, 10 minutes before they actually got her out.”

For two to three years, he said, he lifted heavy weights completely alone. “I was lifting these 65-70,000 pound dies by myself and hanging them up in these bays and these tanks by myself.”

When he raised concerns about safety and contamination, he believed it made him a target. “They got rid of me because I was vocal,” he said. “I’m very vocal about stuff. … You can’t run from me. I’m gonna express my concerns and opinions about it.”

One day during lunch shortly after he raised complaints, he rested his head on top of his toolbox, he said. A Viscofan executive took a photo and accused him of sleeping. Street said he still had time left on his break and wasn’t asleep. The photo was used to put him on a “last chance agreement,” he said. He was later fired for “performance.”

“My performance? I said, ‘I was here for seven years and now all of a sudden my work performance is a problem,’” Street recalled telling his boss.

He said he wasn’t alone. Other workers who spoke up, he said, were also walked out.

And the woman who got her hand caught in the machine? “They just paid her off. Well, don’t say nothing about it,” he said.

The Union Collapse

For years, Viscofan’s union had been a buffer between management and workers — a place employees could take grievances about safety, conditions, and retaliation. But in May of this year, that structure effectively collapsed.

In a May 20 letter to hourly employees that was shared with Hunterbrook, Viscofan wrote that it was “withdrawing recognition” of the local chapter of the union represented by the United Food & Commercial Workers International Union, claiming that a majority had signed a petition requesting the move. Effective immediately, the company suggested, the union would no longer represent them. In the same breath, the CEO of Viscofan’s U.S. operations promised wage increases and new benefits — coming soon.

Whether Viscofan’s move is legal isn’t clear-cut. Traditionally, a union can be decertified through a secret-ballot election run by the National Labor Relations Board. But U.S. law also allows it if an employer has objective evidence the union has lost majority support — as Viscofan seemingly suggested in its letter to employees.

But by pledging raises and benefits in the same letter, the company risked appearing to offer incentives for rejecting union representation — a move that could violate federal labor law.

Michael C. Duff, a professor at the Saint Louis University School of Law and a former NLRB attorney, expressed skepticism about the company’s decision.

“The idea that it put references to improvements in benefits in a letter that it sent all employees suggests to me that either they don’t have the advice of counsel, or it’s possible that somebody doesn’t know U.S. labor law,” he said.

In a letter to Viscofan’s CEO on September 16, four members of the Congressional Labor Caucus also cast doubt on Viscofan’s letter to workers. They declared that the May letter to workers “clearly violates the National Labor Relations Act” and pointed to the company’s alleged attempt last year to pressure employees into signing a petition to weaken the union’s ability to collect dues.

They called on the company to negotiate honestly with the union. Yet today, the future of union protection for Viscofan workers remains unclear, and the union’s May 28 challenge before the NLRB has made little progress.

According to Alec Severins — the head of Vermilion County Watchdog, a community Facebook page — the company’s decision to unrecognize the union came shortly after he began looking into claims of runoff behind Viscofan’s anhydrous tanks and sharing concerns with union representatives. “Their union is real big on safety,” he said.

He described it as the tipping point in what had already been years of escalating tension between management and organized labor. “Union troubles have been going on for a few years,” he said. “But we haven’t seen anything like this happen.” (In 2019, workers at Viscofan’s Danville plant went on strike, leading the company to quickly sign a new collective bargaining agreement.)

Since then, Severins said, many employees feel they’ve been left with no option but silence. “Right now, since the union’s gone, they feel like they can’t speak up,” he said. “They’ll be retaliated against.”

The collapse of the union also coincided with a quiet shift in Viscofan’s workforce. Lake, the former lab employee, and one other employee said that by 2022, as much as 75% of Viscofan’s workforce in Danville had been hired from the company’s plants outside of the continental U.S. (Viscofan has manufacturing sites in Spain, Brazil, Mexico, Germany, China, and seven other countries outside of the U.S.).

Viscofan declined to comment on the makeup of workers at its Danville facility or the legality of its decision to withdraw recognition of the union.

Tim Miller, a former Viscofan employee, wrote in a post on Facebook that the shift in hiring practices was tied directly to the union’s weakening over the years. Without local hires and without a powerful union, he wrote, there were fewer protections. “They want to rid this place of the union and turn it into a minimum wage hell hole,” he wrote. “Bottom line. It’s their way or the highway. They show no respect for a binding CBA.”

Street, the former maintenance worker, echoed similar concerns. He said a strong union had once been a line of defense against dangerous conditions and retaliation. Without it, workers feared the worst.

“Now that these guys won’t have union representation, it’s going to be even worse,” he said. “Who you gonna go tell?”

Viscofan declined to address any of the allegations raised by workers — including unsafe working conditions, uncontrolled pollution, inadequate emission controls, and reported retaliation against those who spoke out. Instead, a spokesperson for the company insisted that it met “strict local and international standards for quality, safety, and employee well-being.”

No Protection

Viscofan’s Danville plant relies on highly toxic and corrosive chemicals, but former workers say basic protective gear was scarce and safety protocols were rarely enforced.

One former worker in the chemical department said he was routinely burned through his gloves by caustic substances. “You were on a two-pair-of-gloves limit a week,” he said. “As soon as your hand hit caustic, the gloves were ruined.”

“I don’t know how many pairs of gloves I was basically forced to wear, because they’re like, ‘No, I can’t give you any more — I’ve reached the limit,’” he added.

He recalled finishing shifts with his pants and shirts soaked in chemicals. “That stuff gets on you — it burns you,” he said. “I’ve probably still got scars on my hands.” Workers were told to rinse chemical burns with soap and water — a method he later found out could irritate the caustic even further. When he tried to raise concerns about exposure risks or ventilation, he said little changed. “Unless there’s a life or death situation, they pretty much brush it off,” he said.

Gonzalez, who worked for two years at the plant, recalled asking his supervisors to replace a drip pan in the plant — a metal tray meant to catch chemicals. The existing one, he said, had been removed, leaving chemicals dripping onto him for months.

“It took them about three months to put another drip pan on there,” he said. “I feel like they don’t really care about their employees at all.”

Johnson, the longtime Viscofan worker who first joined the plant under Teepak in the 1970s, added that respiratory protection was almost nonexistent at first. “They didn’t have masks or anything else. You just did what you wanted,” he said. In his later years, he noticed management began encouraging younger workers to wear masks, but never enforced it across the board.

Brady, who worked in Viscofan’s lab for more than four years, recalled trying to evacuate a workspace due to gas levels above the safety threshold. “As I proceeded to do that due to the exhaust fans not working,” she said, “the supervisors and the higher-ups in management said they are fine and to keep working — and refused to evacuate the employees.”

Others voiced even deeper distrust. Some former lab workers alleged that they had been asked to falsify internal safety data — and that outside oversight was limited. “Every time somebody tries to make a complaint to OSHA, nothing ever gets done,” said Lake, who said she was responsible for recording Viscofan’s gas levels inside the plant.

“I was told by the person training me to only write down good numbers and not to bother the supervisors about the bad readings because they would not do anything anyway,” she recalled.

When she did record actual gas levels and reported them once they became concerning, her warnings were dismissed. She said she was told that “there was nothing they could do because their hands were tied by the owners of Viscofan.”

Several others echoed the sentiment, saying they believe regulators routinely ignored or overlooked issues.

Even major safety certifications, one worker alleged, were treated like pageantry. Street said the plant’s BRC audits usually ended with a barely passing grade. When a new auditor came in, he initially failed the facility outright. A month or two later, he returned and gave the plant a glowing score. Street said nothing changed between the two visits, with the exception that Viscofan “hadn’t swayed him” the first time around.

Despite years of allegations, Viscofan has faced limited OSHA enforcement. The most serious, and expensive, action came only in July 2024, when the agency cited Viscofan’s Danville facility for one repeat violation, seven serious violations, and one other-than-serious violation. The initial penalties totaled just under $200,000 and documented incidents where workers were hospitalized, caught in rollers, and burned with hazardous chemicals, all with insufficient preventative action taken by the company.

But according to photos of notices posted inside the plant and obtained by Huntebrook, Viscofan has received at least three complaints since 2022. The complaints allege that workers were exposed to shock and burn hazards, unlevel and trip-prone working surfaces, and harmful levels of carbon disulfide and ammonia — claiming the plant had “not implemented controls” to remove hazardous gases from the breathing area.

For now, oversight has come in bursts before fading back into the hum of daily life. On paper, the system has worked: the penalties are paid and the doors stay open. But in Danville, the air still smells the same.

In town, there’s perhaps no one who knows Viscofan better than Deborah Stacey. She lives just across the road, in a sagging house where the lawn has grown wild and chairs and tables lie flipped all around.

She’s a squatter, sick with cancer — and she’s learned to live with the industrial hum, and smell, that settles over her front porch every night.

“Sometimes you gotta have bad odor with good odor, you know,” Stacey said. “Because if we ain’t got the bad odor, then you might as well forget the good one.”

Author

Dhruv Patel is an investigative journalist based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, specializing in data-driven reporting. He helps spearhead investigative coverage at The Harvard Crimson, and his reporting has been cited and discussed by The New York Times, CNN, The Boston Globe, ABC News, and BBC, where he also frequently contributes commentary. A John Harvard Scholar at Harvard College, he studies computer science and economics to leverage machine learning for accountability journalism.

Editor

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar (taking much easier classes than Dhruv!) and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Graphics by Daniel DeLorenzo and fact-checking by Wendy Nardi and Jon Ponciano.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please email ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work, or press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.