Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $HIMS at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

By Thursday, the FDA will likely decide whether a key GLP-1 weight loss drug ingredient is still in shortage. The ruling will reshape the regulatory landscape and impact the future of Hims & Hers Health (NYSE: $HIMS), one of the fastest-growing and most controversial players.

Hims, widely known as provider of hair loss treatments and erectile dysfunction pills, has transformed into a major player in America’s weight loss gold rush by selling GLP-1 drugs. But that business exists not because Hims has developed and gained approval for such a drug, but rather due to a regulatory quirk: if the FDA determines there is a “shortage” of a particular drug, so-called “compounding” pharmacies can produce non-brand name versions of FDA-approved drugs, which companies like Hims can then offer patients at a cheaper price than name-brand versions.

Compounded drugs differ from FDA-approved “generics” too, in that “FDA does not verify the safety, effectiveness or quality of compounded drugs.”

For much of this year, the key ingredients across two categories of GLP-1 drugs were designated in shortage: tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) and semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy).

In October, Tirzepatide was removed from the shortage list, a decision the FDA said it will update by Thursday.

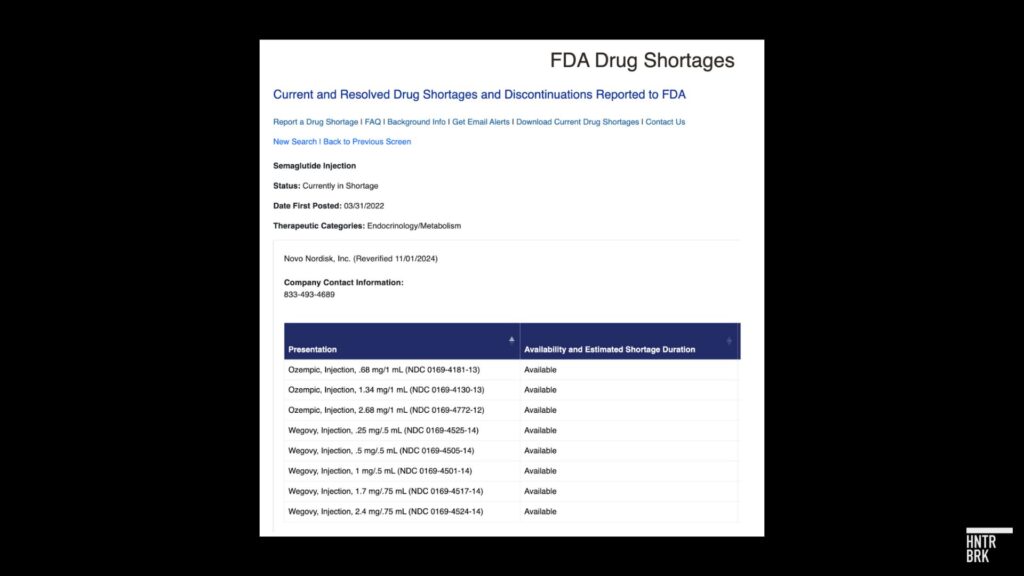

The decision on semaglutide is expected soon as well — with Novo telling Hunterbrook in a statement that it is “happy to share that the status of all our GLP-1 medicine presentations for Ozempic and WeGovy are now reflected on the FDA shortage website as, ‘Available.’”

“All doses of these products are being shipped regularly to wholesalers,” the company added, reiterating that it is “deeply concerned about companies promoting and selling compounded, non-FDA approved knock-off versions of ‘semaglutide.’”

A Hunterbrook investigation earlier this year revealed concerning practices at Hims.

Patients could get compounded semaglutide from Hims through brief online questionnaires without speaking to doctors. The company’s supplier, meanwhile, operated under a corporate umbrella with a history of fraud allegations.

In the following months, Hims strengthened its prescribing requirements, updated SEC risk disclosures, and offered customers certificates of analysis for their medications. Independent laboratory testing commissioned by Hunterbrook later confirmed that samples from Hims contained genuine semaglutide, unlike counterfeit providers in the market. Hunterbrook published a follow-up on the potential benefits to Hims from the nominee for FDA commissioner, who was chief medical officer of a telehealth company that sells compounded GLP-1s.

But now the shortage that enables much of this business appears to be on the verge of ending — potentially before that FDA commissioner takes office — which would force Hims to pursue more creative options.

“The Manufacturer Is Pushing Out Inventory”

In June, Dr. Angela Fitch, past president of the Obesity Medicine Association, told Hunterbrook she expected the GLP-1 shortage to stretch indefinitely. Her pharmacy was sending regular updates marking most doses unavailable. Dr. Fitch told Hunterbrook Media she has consulted with a wide range of clients in the past, including Lilly, Novo, Vivus, Rhythm, Currax, Jenny Craig, Seca, and Sidekick.)

Six months changed everything.

“No shortages here in Boston,” Fitch said this week. The pharmacy’s tracking sheet that had once showed red and yellow warnings is “all green.”

When asked by Hunterbrook, a pharmacy technician at a rural Minnesota Walgreens had a similar report. He said that, while some doses remain “on allocation” with ordering limits set by distributors, the pharmacy has been able to meet patient demand for months.

Ricki Chase, former director of the Chicago District Investigations Branch of the U.S. FDA’s Office of Regulatory Affairs, agrees. “Tirzepatide is not in shortage. That’s not a question,” said Chase in response to inquiries from Hunterbrook. “The manufacturer is pushing out inventory.”

In yet another sign that the shortage may be over, last week, telehealth company Ro announced a partnership with Lilly to distribute tirzepatide — enabling patients with a prescription to access the FDA-approved, name-brand version of the drug online. Lilly also offers telehealth prescriptions of vials of its GLP-1 drugs directly.

“If you’re expanding partnerships… I feel you can definitely make a case that there isn’t a supply issue,” said Paul Cerro, a Hims investor and former Ro employee who still holds equity in Ro. Lilly’s decision to partner with Ro “speaks volumes,” he added, noting that he no longer has a relationship with the company or knowledge of its plans.

The GLP business, he said, was one of the reasons he felt Hims had promise, calling it the company’s “next Moby Dick.”

“Hopefully, in this instance,” he added, “you just don’t want the whale to attack you at the end.”

Neither Hims, Ro, nor Lilly responded to Hunterbrook’s requests for comment at the time of publication.

Legal Limbo: How the FDA’s Decision Could Reshape the Weight Loss Drug Market

The regulatory framework enabling Hims & Hers’ GLP-1 business rests on the FDA’s drug shortage designations. Under Sections 503A and 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, compounding pharmacies can mass produce and distribute versions of FDA-approved drugs only if those drugs are designated by the FDA as being in shortage.

This exemption has allowed companies like Hims & Hers to help meet surging demand for GLP-1 drugs such as tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound) and semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) at a significantly reduced price compared to branded alternatives. (Hims currently only prescribes the latter.) But the FDA’s recent regulatory moves threaten to undermine this business model.

Tirzepatide’s Shortage Status Sparks Legal Battle

In early October, the FDA updated its list and declared the shortage of tirzepatide over, citing sufficient manufacturing capacity and product availability. In light of the high demand for their tirzepatide and semaglutide products, Lilly and Novo have both made billions worth of investments to expand their production capacities.

According to FDA standards, a drug’s shortage status is considered “resolved” when “all the manufacturers combined are able to meet total national pre-shortage supplies” or the current market need, with the agency verifying the presence of safety stock. The FDA said it had enough data to confirm adequate availability of tirzepatide, effectively ending the exemption for compounded versions of the drug.

The FDA generally gives a 60-day grace period to allow 503B compounding pharmacies to fulfill any product orders it began working on while the drug was still in shortage. See FDA Draft Guidance “Interim Policy on Compounding Using Bulk Drug Substances Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act” footnote 21; and FDA Final Guidance “Compounded Drug Products That Are Essentially Copies of Approved Drug Products Under Section 503B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act” footnote 18. After that, any compounders still selling the drug are subject to enforcement action.

The tirzepatide shortage is “Resolved” on the FDA website. Semaglutide is “Currently in Shortage,” though all versions of Ozempic and Wegovy are listed as “Available.” Both Fitch and the Walgreens pharmacy technician told Hunterbrook they’re no longer having challenges getting it.

Another leading drug shortage tracker, from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, also shows availability of tirzepatide and semaglutide. There are subtle differences in how the FDA and ASHP track shortages, with the latter often including more drugs than the FDA as it reflects supply chain disruptions beyond manufacturer capacity.

Both drugs fall under the broader GLP-1 weight loss drug category, but differ in their mechanisms and market availability.

The FDA’s decision on tirzepatide was met with swift legal action. On October 7, compounding pharmacy advocacy groups, including the Outsourcing Facilities Association, sued the FDA, arguing that the agency did not follow the appropriate procedure and that its determination was based on flawed metrics that give an incomplete picture of demand for tirzepatide.

“The FDA’s removal of Tirzepatide from the shortage list without the due process of proper federal notice, at a time when they acknowledge that shortages still exist, is the definition of arbitrary and capricious,” said Lee Rosebush, chairman of the Outsourcing Facilities Association, in a press release. Rosebush is a partner at the law firm Baker & Hostetler LLP, where he leads the Pharmacy & Reimbursement Team and co-leads the FDA Law Practice. On LinkedIn, the Outsourcing Facilities Association address listed is the address of Baker & Hostetler’s office near Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C. “The agency’s decision will have tremendous implications across the nation for patients and physicians, as well as the outsourcing facilities that made an enormous investment to meet patient demand in light of product shortages and delays.”

Gaps in Access Fuel Legal Pushback

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit accused the FDA of ignoring supply realities on the ground.

“The only basis FDA offered for its declaration of victory over the shortage was the ‘stated product availability and manufacturing capacity’ of the drug’s manufacturer — the company that is self-interested in monopolizing the market,” the complaint read. The plaintiffs contended that localized access challenges, compounded demand, and affordability issues for patients were not sufficiently considered in the FDA’s assessment.

The plaintiffs also threw in a reference to the June U.S. Supreme Court decision in Loper Bright — which overturned decades of precedent deferential to agencies under the Chevron doctrine — as authority that the court should interpret parts of the Food Drug & Cosmetic Act regarding shortages without deference to the FDA.

Neither plaintiff responded to Hunterbook’s requests for comment.

OFA also submitted a comment to the FDA that argues the semaglutide shortage remains ongoing: “OFA conservatively estimates that roughly 80 million prescriptions for semaglutide were fulfilled with compounded semaglutide in the last 12 months, inclusive of 503A pharmacy compounders and 503B outsourcing facilities. These compounded products are fulfilling demand that is not being fulfilled by the manufacturer. Absent a demonstration by the manufacturer that it can readily supply more than 80 million prescriptions, semaglutide remains in drug shortage.”

Hims has also pushed back against the FDA. The company submitted a public comment in November and launched its own GLP-1 Supply Tracker to gather evidence of shortages, reporting that “nearly 80,000 customers” have indicated difficulties accessing these medications through pharmacies. Hims argued that compounded GLP-1 drugs serve an essential role in addressing unmet demand, claiming that “nearly 30% of Weight Loss customers who had been prescribed a branded GLP-1 product in the past were unable to fill it because the medication was not available at their pharmacy.”

The Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, another industry group, also contends that the shortage is ongoing, sharing screenshots from pharmacies showing limitations on their ability to order tirzepatide.

FDA’s Decision Delayed by Lawsuit

The lawsuit forced the FDA to quickly consider the compounders’ grievances, and the agency requested a remand to reevaluate its decision on tirzepatide’s shortage status. In its October 11 motion, the FDA committed to reconsidering its determination and agreed not to take enforcement actions against compounders for violations tied to the drug shortage exemption until two weeks after its final decision.

As of now, the FDA’s reevaluation is ongoing, with the next joint status report due on Thursday. Plaintiffs have continued providing what they say is evidence of limited access, including survey data showing that patients in certain regions are still having difficulty getting branded tirzepatide. One filing referenced distributors listing the drug as “out-of-stock or available only in limited quantities,” suggesting gaps in the supply chain despite the FDA’s confidence in Eli Lilly’s manufacturing capacity.

“The FDA generally does not comment on ongoing litigation,”a spokesperson for the FDA told Hunterbrook.

“Pick Your Poison”

Both stories could be true.

Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly may very well be producing adequate stock of semaglutide and tirzepatide to meet national demand, while patients still struggle to access the drugs due to logistical challenges. Cold chain storage, ordering practices, and the capacity of local pharmacies can create bottlenecks that leave patients unable to obtain their prescriptions even when supply appears sufficient on a national level.

But historically, these localized barriers haven’t factored into the FDA’s decisions on drug shortages, according to Chase. “Either the manufacturer can supply or they can’t and FDA uses this shortage list to try to inform and to allow for supply outside of the normal approval process,” said the former FDA investigations branch director. “It was never intended to be a free for all for compounders.”

By law, in other words, what matters is whether manufacturers are producing enough product to satisfy the market overall — not whether every patient has equal access to the drugs. This narrow definition puts the FDA in a bind.

Plaintiff OFA has indicated that if FDA reaffirms that the shortage is resolved, it will not simply accept that determination. “Should the FDA repeat its removal decision when a shortage still genuinely exists, we will return to court,” Rosebush said in a press release.

But on the other hand, if the agency sides with the compounders and reverses its decision on tirzepatide’s shortage status, it risks opening itself up to lawsuits from big pharmaceutical companies like Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, companies whose market dominance could be undercut by the production of compounded versions — and who made billions of dollars in production investments to keep up with demand.

These companies, Chase noted, may be losing billions of dollars due to compounding. If the FDA doesn’t stop that, “the next people they’re going to be sued by are the innovator companies,” she said. “Pick your poison.”

Last month, Sens. Tim Kaine and Tom Cotton and Reps. Abigail Spanberger, and Adrian Smith, introduced bipartisan legislation in both houses of Congress that would modify the FDA definition of a shortage. The End Drug Shortages Act — which would add “surges in demand” to manufacturer reporting requirements and direct the FDA “to consider reports from patients and health care professionals” when evaluating shortages — is unlikely to go anywhere this session, but it hints at a possible legislative package for next congress, according to Politico.

Cold Storage and Access Challenges: The Final Hurdle in GLP-1 Availability

While the FDA may determine that the national supply of tirzepatide and other GLP-1 medications is sufficient to meet market demand, the reality for patients often tells a different story.

Even when manufacturers report robust production and distribution, logistical barriers — particularly those related to cold chain storage and pharmacy practices — can impede access.

As the FDA itself acknowledges on its drug shortages portal, “Patients may not always be able to immediately fill their prescription at a particular pharmacy. That is especially true for refrigerated products and products with multiple dose strengths.”

Fitch highlighted these issues, explaining that cold chain coordination plays a significant role in determining patient access. “CVS doesn’t have big enough refrigerators,” she noted, adding that “pharmaceutical production is improving greatly and someone should now consider focusing on how to better manage the cold chain supply situation. As companies make more drugs, we need more reliable ways of getting it to people in a timely manner.”

Chase agreed that even when the national supply chain is stable, localized logistics often remain the bottleneck. “What will delay you getting that drug is cold chain logistics and pharmacies buying it—or not buying it—where you’re located,” Chase explained. Rural areas, in particular, often experience longer delays due to the additional challenges of transporting and storing temperature-sensitive medications. “It’s more difficult to get cold chain products in more rural locations. It takes longer because of the way you have to maintain the drug,” she said.

This sentiment was echoed by the pharmacy technician at a Walgreens in rural Minnesota, who described the practical challenges pharmacies face when storing and distributing GLP-1 medications. “We have probably about a 10- or maybe 15-cubic-foot refrigerator,” he explained. “And a good quarter to third of it at any given time now is the GLP-1s. … We routinely don’t have space for all of them” in alphabetically ordered containers, “so we’re tucking them between other drugs just to try to get them in the fridge.”

If a patient needs a dose he doesn’t have in stock, he said, “I can almost always order it and get it quickly.” He added this “wasn’t the case six months ago” — back when GLP-1 drugs were in shorter supply.

Corporate policies, however, have created additional barriers to patient access, he said.

Walgreens recently instituted a policy limiting patients to one-month fills of GLP-1 prescriptions, regardless of their doctor’s orders or insurance coverage, he said. The pharmacy tech speculated that this policy may be driven more by profit considerations than by supply constraints, as most patients use copay cards that reduce their portion of the prescription cost by the same amount whether it’s a one-month or three-month fill.

If Walgreens fills a multi-month prescription with the coupon, they only collect that co-payment once. If Walgreens fills a one-month prescription, they collect the co-payment each month. “Limiting patients to one-month fills means they make triple the revenue in copays,” he noted. Walgreens’ new policy “adds about six layers of fuckery to the workflow for all the GLP-1s.”

Walgreens did not respond to a request for comment.

These dynamics highlight a critical distinction between supply and accessibility. While manufacturers and regulators may focus on aggregate production and distribution metrics, patients face on-the-ground realities shaped by pharmacy practices, cold chain infrastructure, and even geography. As Fitch aptly summarized, “Coordination is the bottleneck.”

What Does This Mean for Hims?

For Hims & Hers, the FDA’s upcoming decision on tirzepatide’s shortage status marks a defining moment.

If the agency formally removes GLP-1 drugs from its shortage list, the regulatory pathway that has fueled the company’s rapid expansion into the weight loss space to this point will become less straightforward, forcing a reckoning with its business model and strategy. But that doesn’t necessarily mean Hims will stop offering compounded weight loss drugs.

The 503A Option

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act allows two types of drug compounding: 503A and 503B. A key distinction between them is the scale of the compounded production: 503B allows “outsourcing facilities” to mass-produce compounded drugs, while 503A permits only “patient-specific” compounding of customized drugs for individual prescriptions. Pharmacists and physicians who compound under 503A also cannot “compound regularly or in inordinate amounts” drugs that are otherwise commercially available.

When drugs are in shortage, certain restrictions on both types of compounding are lifted — which companies like Hims have taken advantage of to offer massive quantities of compounded drugs. Hims even bought a 503B outsourcing facility in California this fall in order to “continue to deliver on sterile compounded products like GLP-1 injections.”

But in the event the FDA lifts the shortage designation, Hims appears to be counting on the narrower 503A process to justify its investments in compounding.

Under 503A, there may continue to be specific, limited situations where compounding tirzepatide and semaglutide can take place, if a healthcare provider determines there is either a “significant difference” or a “clinical difference” between the compounded version and the FDA-approved product. Section 503A(b)(2) of the FD&C Act provides an exception for “a drug product in which there is a change, made for an identified individual patient, which produces for that patient a significant difference, as determined by the prescribing practitioner, between the compounded drug and the comparable commercially available drug product.” Section 503B(d)(2)(B) of the FD&C Act bars compounded drugs that are essentially copies of approved drugs “unless there is a change that produces for an individual patient a clinical difference, as determined by the prescribing practitioner, between the compounded drug and the comparable approved drug.” For example, compounding may be necessary if a patient is allergic to a component of an FDA-approved drug and needs a special formulation without the allergen, or if a patient unable to swallow pills needs a liquid form of a drug they can drink.

Hims has suggested it might continue compounding after the shortage ends — providing custom versions of these drugs.

During the Hims Q3 2024 earnings call, CEO and Co-Founder Andrew Dudum pointed to customization aimed at mitigating side effects as justification for the company to continue compounding drugs for weight loss once the shortage is resolved.

”Given you’re talking about north of 100 million people suffering from obesity in this country and the very, very high side effect rate with these medications, we fully expect that there’s millions of patients that will need that level of personalization, that our platform over the long haul is really well equipped to deliver on,” Dudum said. ”We believe that dosing specifically for this type of a treatment to mitigate side effects is very much right down the center of what that compounding exemption is built for.”

A recent bullish note from Morgan Stanley argued that Hims is “well positioned to transition the compounding process from 503B to 503A pharmacies,” claiming that 503A pharmacies are regulated at the state level, rather than by the FDA.

Such a move, however, could provoke enforcement actions — or lawsuits from manufacturers like Lilly.

Novo and Lilly are keen to prevent competitors like Hims from exploiting the 503A option. Both companies have requested the FDA add semaglutide and tirzepatide, respectively, to its “lists of drug products that present demonstrable difficulties for compounding.” These DDC Lists identify substances that are considered particularly risky to compound, and drugs on these lists cannot be compounded under either 503A or 503B — which could be the biggest problem for companies like Hims. DDC lists do not yet exist, though the FDA is required by law to create them. The agency published a Proposed Rule to establish criteria for DDC lists on March 20, 2024, but the Proposed Rule has not yet been finalized.

“The nomination of semaglutide to the FDA’s Demonstrable Difficulties for Compounding (DDC) Lists is a significant step towards keeping people safe from unapproved and potentially harmful versions of knock-off ‘semaglutide’ drugs,” a Novo spokesperson told Hunterbrook. “These drugs are inherently complex to compound safely, and the risks they pose to patient safety far outweigh any benefits. Novo Nordisk’s aim with this nomination is to ensure that patients receive only FDA-approved, safe, and effective semaglutide products.”

“The FDA is reviewing the petition and will respond directly to Novo Nordisk,” an FDA spokesperson told Hunterbrook.

While Novo submitted a citizen petition for its semaglutide nomination, Lilly nominated tirzepatide to the DDC via public comment on an open rulemaking docket. “The latest information about the proposed rule can be found on the Federal Register. The agency is in the process of reviewing comments for consideration in issuing a final rule,” the FDA spokesperson said.

Novo is also taking legal action against compounders, telling Hunterbrook it has filed “63 lawsuits nationwide, across 19 states, against medical spas, weight-loss clinics and compounding pharmacies engaging in unlawful marketing and sales of compounded drugs claiming to contain ‘semaglutide.’” Novo provided links to three press releases highlighting some of their legal actions: May 30, 2024 release; June 20, 2023 release; November 29, 2023 release. The company also said “Our ongoing efforts, detailed on semaglutide.com, are geared towards protecting patients and ensuring they have access to safe and effective FDA-approved medicines.” The company said it will continue to pursue legal recourse “against other entities engaged in similar conduct.”

This raises the question: Given the uncertainty around the future of compounding for these drugs, will Hims transition away from compounding, or will it gamble on prolonging its high-margin business and risk legal blowback?

Transitioning to Branded Medications

If Hims exits compounding, a viable alternative would be to distribute FDA-approved branded GLP-1 drugs approved for weight loss, like Mounjaro or Wegovy. In its Q3 2024 letter to shareholders, Hims indicated it intends to offer branded medications once the company is able “to gain consistent supply of these medications.” But this pivot would come with challenges.

For one, branded GLP-1 medications come with steep price tags, even for patients with insurance, which could alienate Hims’ cost-conscious customer base. When asked whether the company would build out capacity for insurance reimbursement on branded GLP-1s during Hims’ most recent earnings call, Dudum said “the cash pay market is probably our approach.”

There is also far more competition in the branded space, with doctors offices across the country prescribing the name-brand drugs — and competitors better positioned due to partnerships like the one between Ro and Eli Lilly.

It may also mean lower margins for Hims. In a Bank of America note published on Monday, the analyst argues that “brand mail pharmacy margins can be 5-10% (and in many cases pharmacies are losing money on GLP-1 scripts), which are significantly lower than the 50% gross margins we estimate HIMS is capturing in its GLP-1 portfolio.”

“It is unlikely that HIMS will follow Ro’s lead to partner with brand manufacturers,” the analyst added, because “HIMS’ differentiation and success is tied to its own brand equity for its products” and “selling branded pharmaceutical drugs would both hurt margins and cannibalize its core products.”

Diversifying Beyond the Major GLP-1 Drugs

Hims could also look to broaden its weight loss offerings, leveraging its established telehealth platform to incorporate non-drug-based solutions.

This might include one-on-one coaching and educational tools to complement weight loss medications. Currently, Hims says it offers “evidence-based content, tips and tricks, and convenient recipes” to its weight loss customers. This support seems to rely on consumers using tracking tools in the Hims and Hers apps that will algorithmically recommend content based on user responses.

Hims also recently launched meal replacement packages of diet bars and shakes “to complement each individual’s weight loss plan, especially those patients losing weight on GLP-1 medications.” These start at $110/month.

And finally, Hims may continue exploring medications or treatments for obesity that aren’t subject to the same regulatory limitations.

Hims already offers “personalized medication kits” consisting of generic or compounded pills for weight loss and can include combinations of the drugs “metformin, bupropion, topiramate, vitamin B12, and naltrexone” that are around $79/month, and plans to begin offering a generic GLP-1 called liraglutide in 2025.

During the Hims Q3 2024 earnings call, Dudum confirmed the company had “already confirmed a core supplier” for generic liraglutide, a drug whose branded version is sold by Novo Nordisk under the brand names Victoza and Saxenda for Type 2 diabetes and weight loss, respectively.

Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries (NYSE: $TEVA) began marketing the authorized generic of Victoza this June, and Teva CEO Richard Francis told investors during the Q3 2024 earnings call that the company plans to launch generic Saxenda in 2025. Former Novo exec and former Teva CEO Kåre Schultz joined the board of Hims in July.

Several other companies have entered settlements with Novo Nordisk related to generic liraglutide products. Hikma Pharmaceuticals (LON: $HIK) won tentative approval for its generic this June.

Author

Laura Wadsten is a journalist based in Washington, D.C. She is also Executive Director of the nonprofit Moving to Value Alliance, where she produces and occasionally co-hosts the MTVA Unscripted Podcast. Previously, Laura wrote about antitrust and health care markets as a Correspondent for The Capitol Forum, a premium subscription financial publication.She was a Hodson Scholar at Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a B.A. in Medicine, Science & the Humanities.

Editor

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.