Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $HIMS at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

On December 18, Hunterbrook reported on the looming end of the shortage for the blockbuster GLP-1 drug tirzepatide and what it could mean for companies like Hims & Hers Health — which have been using a regulatory exception that allows companies to sell “compounded” versions of FDA-approved drugs during shortages.

As the Hunterbrook article predicted, the following day, the Food and Drug Administration resolved the shortage on the weight-loss drugs Mounjaro and Zepbound. After the news broke of the FDA’s decision, Hims saw its share price fall by as much as 15%.

A silver lining for Hims was that, the day the FDA lifted the tirzepatide shortage, the agency reiterated that semaglutide — the GLP-1 drug offered by Hims — was still considered to be in shortage. That meant, for the moment, Hims could continue providing compounded GLP-1 drugs to customers.

But that consolation may be short-lived.

Novo Nordisk, the manufacturer of Ozempic and Wegovy, told Hunterbrook in a statement that all doses of its semaglutide drugs are available — which has been reflected on the FDA’s website since October.

And Hunterbrook’s data analysis indicates that, once a manufacturer reports all doses of a drug are “available,” the FDA generally lifts the shortage designation within two months, if not quicker — with only rare exceptions.

The FDA ending the semaglutide shortage could significantly impede Hims’ GLP-1 business — as the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act prohibits compounding of products that are “essentially a copy” of another drug on the market, unless the copied drug is labeled as “currently in shortage” on the FDA’s drug shortage list. The “essentially a copy” prohibitions are codified as section 503A(b)(1)(D) and Section 503B(d)(2) of the FD&C Act. The FDA defines the shortage exception in two 2018 guidances for 503A and 503B compounding.

This means when the FDA resolves a drug shortage, the exception to federal laws prohibiting copycat compounded drugs goes away, rendering compounding illegal.

With All Doses of Semaglutide “Available,” FDA Likely To Act Soon

All forms of semaglutide have been labeled “available” since October 30, about 62 days ago, according to the FDA’s drug shortage database.

That’s the same number of days it took for tirzepatide to go from being listed as “available” on the FDA’s website in August to its shortage being officially resolved in October. (After a legal challenge by compounders, that tirzepatide shortage resolution was then postponed until December 19.)

There’s no prescribed timeline for the FDA to resolve a shortage once it reports a product is available. The law governing shortage monitoring only requires the agency to “maintain an up-to-date list of drugs that are determined by the Secretary” of Health and Human Services, the FDA’s parent department, “to be in shortage in the United States,” and the FDA website notes that it updates the shortage list daily.

“The FDA cannot provide a general timeline for when a drug may come off the shortage list because each drug shortage is assessed on a case-by-case basis,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Hunterbrook. “The FDA continues to actively monitor drug availability and is currently working to determine whether the demand or projected demand for semaglutide within the U.S. exceeds the available supply.”

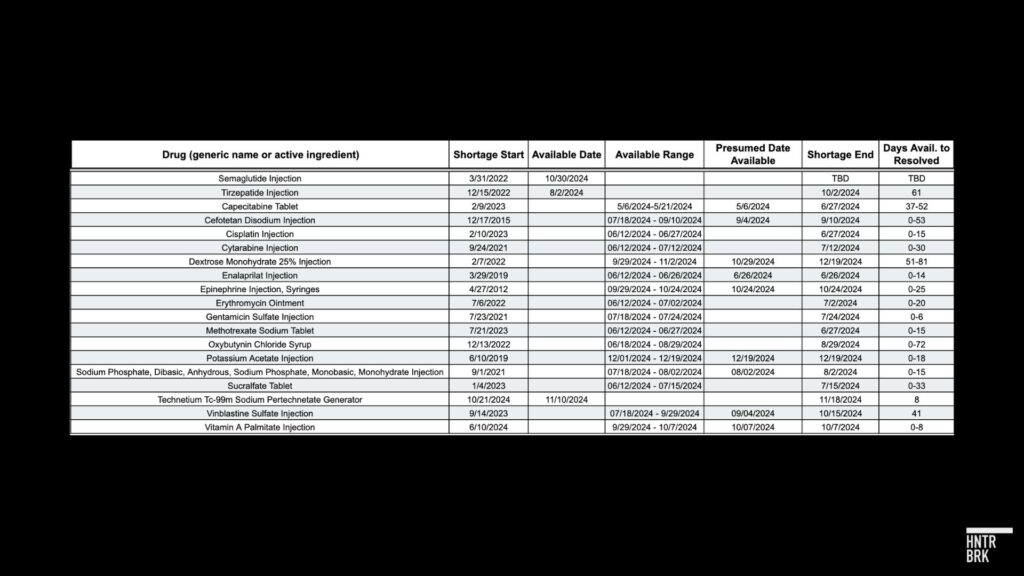

To estimate the average time between the initial reporting of product availability and the resolution of shortages, Hunterbrook analyzed historical data on drug shortages resolved by the FDA over the past several months. We collected archives of the FDA drug shortage database and searched for updates on availability and resolution for 18 drugs, including tirzepatide. For products in shortage with multiple versions (i.e., multiple dosage strengths, forms, or manufacturers), Hunterbrook determined a product in shortage to be available once all versions of the listed product were available.

The archived data of the FDA shortage website is incomplete: Hunterbrook couldn’t find data from every single day of the search period for the products compared. As a result, the estimates for many of the comparison timelines are provided as ranges.

The “Available Date” column shows dates that are certain. “Presumed Date Available” contains our best estimated date when the product was first reported available but for which there is a range (see “Available Range” column) rather than a certain date. While the FDA initially resolved the tirzepatide injection shortage on October 2, 2024, the final resolution of the shortage was delayed by the compounders’ lawsuit until December 19, 2024. That whole process took 139 days.

Based on this analysis, between June and December of this year, it has taken an average of about 20 days for drugs to go from being listed as “available” to shortages being officially “resolved” by the FDA. In two cases, the time between when the product was first available to when the shortage was alleviated is certain: eight days for Technetium Tc-99m Sodium Pertechnetate Generator, and 61 days for the tirzepatide shortage.

Hunterbrook also looked for cases where drugs were marked as “available” before again being designated “unavailable” — and remained on the shortage list for years. One rare case was identified: Letermovir Injection was marked available in December 2019 but remained on the shortage list until late 2021.

The approximately 60-day decision making time frame for tirzepatide, however, was mentioned as standard in several of Hunterbrook’s discussions with close observers.

David Rosen, a lawyer and pharmacist who worked at the FDA for 14 years, told Hunterbrook the process of resolving a shortage once the product is available “should be relatively quick.”

“When I say relatively quick, I’m saying 60 days, somewhere in that ballpark,” Rosen said. Rosen is a partner at Foley & Lardner LLP, where he leads the FDA Practice Group.

Other analysts and former FDA officials repeated that the agency aims to lift a shortage in around that time frame.

Between reporting a drug is available and declaring a shortage is over, the FDA’s drug shortages staff may communicate with manufacturers and wholesale distributors to confirm adequate supply and availability.

According to Rosen, it’s a “pretty straightforward” determination by the FDA that a shortage has been resolved: “Do they have sufficient materials in the supply chain, and can they meet the market demand for the product?”

“In my experience, FDA wants at least one year of finished goods in stock, and six months or more of raw materials to be able to continue to make sure that the pipeline is secure,” Rosen said. “In this situation, there might even be more because the demand has been so great.”

And taking time before declaring a shortage over can further the agency’s public health mission. “What they don’t want to do is stop everybody from compounding, have the product not being available, create more of a problem for people that have been already on it,” Rosen said.

Rosen expects the FDA will resolve the semaglutide shortage “in the near future,” though he was skeptical that the agency will make the decision this week.

“A lot of people aren’t working, I mean, it’s the end of the year,” Rosen said. “At least in my experience, at the end of the year, they were trying to get the end-of-the-year approvals out, to add to the calendar-year approvals.”

Ricki Chase, a former director of an FDA Investigations Branch, shared a slightly different perspective. “The FDA is weird because the administration comes in on January 20th — and the FDA is already almost halfway through their fiscal year at that point. The second half of their fiscal year is their hard push. So they don’t want distractions.”

In her view, this means the FDA will move as quickly as it can to resolve the shortages, especially given the incoming administration’s links to GLP-1 compounding, which Hunterbrook has reported on in the past.

“The unknown feels big with this administration especially because there is a tie to the compounding business,” said Chase. “So I think if they can resolve as much as possible between now and January 20th, they’re going to do it.”

Novo Nordisk Asserts Semaglutide Is Widely Available

A spokesperson for Novo Nordisk told Hunterbrook that all doses of Ozempic and Wegovy “are being shipped regularly to wholesalers.”

This aligns with Hunterbrook’s previous reporting. Dr. Angela Fitch, past president of the Obesity Medicine Association, shared screenshots with Hunterbrook of GLP-1 inventory tracking sheets for Pharmacy Direct in Boston, Massachusetts. The tracker showed Ozempic and Wegovy were fully available as of December 3.

A pharmacy technician at a Walgreens in rural Minnesota also told Hunterbrook he no longer has issues getting enough semaglutide products to meet patient demand.

Novo’s advertisements promoting its semaglutide product Wegovy could be another indicator of sufficient supply, according to “Bayside,” a poster in online investor forums — including Hims House, a community that includes owners of the company’s stock — who identifies themself as a healthcare lobbyist and successfully predicted the resolution of the tirzepatide shortage.

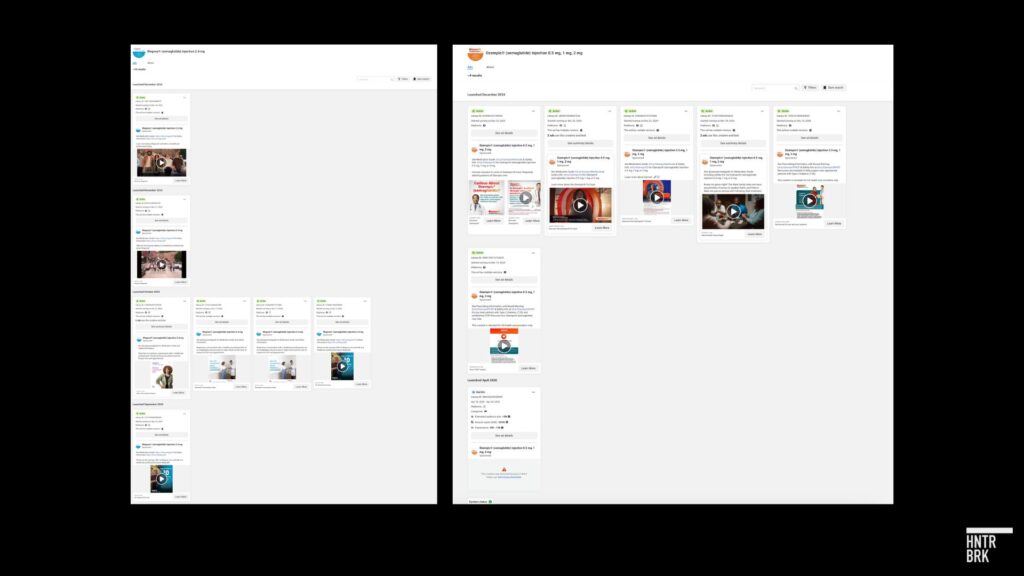

A Meta ad library search by Hunterbrook revealed campaigns for Wegovy beginning in late October, which aligns with the timeline of when Novo’s products became “available” on the FDA shortage database, as well as two other campaigns launched between November and December. That brings the total number of “active” Wegovy ads in the Meta ad library to 11. For comparison, Wegovy appears to have had just one ad running on Facebook this year before June.

Novo appears to have begun advertising Ozempic on Facebook in December for the first time since 2020.

Novo has also been hitting the airwaves — spending an estimated $14.6 million on Ozempic TV ads in October 2024, according to the real-time ad tracker iSpot.TV, “up from $10.8 million in September.” The company spent $41.9 million on TV ads for Wegovy in November, giving the drug the third largest TV ad spend in the U.S. that month.

As Bayside pointed out, a Reddit user complained that Wegovy ads “are played incessantly during sporting events” and another responded “I don’t watch sporting events and I have seen this bizarre commercial so many times it’s becoming part of the fabric of my life… very disturbing.”

Advertising, Bayside argued, was “an interesting thing to do when you are trying to control demand to end a drug shortage.”

Bayside said they also conducted their own channel checks of availability. According to one of their reports shared in Hims House, branded semaglutide is most likely to be available at large pharmacies like Walmart, Sam’s Club, Amazon Pharmacy, and Costco — and less likely to be found at certain smaller pharmacies, due to supply chain dynamics. Bayside claimed to have reached this conclusion after compiling patient-reported data from Reddit and inquiring in person at a handful of retail pharmacies.

Bayside predicted on December 16 that “tirzepatide is 80% likely to come off shortage this week,” which proved true, and asserted, “I think there is a 50% chance the same thing happens with semaglutide, either this week or next.”

After the tirzepatide decision, they raised their estimate to 80%.

In the tirzepatide determination, the FDA clearly stated its legal authority to make its own decisions about ending shortages

As the FDA’s semaglutide decision looms, the agency continues to go back and forth with compounders on tirzepatide.

In the public letter broadcasting its tirzepatide decision, the FDA cited data from manufacturer Eli Lilly.

“The information and data Lilly has provided to FDA demonstrate that Lilly’s supply is currently meeting or exceeding demand for these drug products, and that Lilly has developed reserves that it now holds in its finished product inventory, plus significant units of semi-finished product, and has scheduled substantial additional production over the coming months, such that supply will meet or exceed projected demand,” the agency wrote.

The FDA is offering an enforcement grace period for compounders to stop their tirzepatide operations. The agency stated in its letter that it will not begin enforcement against compounding outside of a shortage until February 18, 2025 (60 days), for 503A compounding pharmacies, and until March 19, 2025 (90 days), for 503B outsourcing facilities.

503A compounding pharmacies are bespoke operations serving individual patients, such as providing a personalized version of a medicine for a patient with an allergy to a typical ingredient that is absent from the compounded version. 503B facilities can mass-produce compounded drugs. A table outlining key legal differences between 503A and 503B compounding can be found on the FDA’s website.

As previously reported by Hunterbrook, the FDA typically gives 503B outsourcing facilities 60 days to wind down compounding before taking enforcement action. There is no prescribed window of deferred enforcement for 503A compounders outlined in FDA guidance. The extended grace period could help assuage aggrieved compounders.

But the Outsourcing Facilities Association didn’t exactly seem satisfied by the FDA’s decision. In a statement, the OFA wrote that it “fundamentally disagrees with the FDA’s determination,” arguing the agency was operating based on “the manufacturer’s say-so.”

“The OFA will continue its efforts to hold the FDA accountable for its obligations under law and duty.”

The OFA did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment by press time.

Another compounding trade group, the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, thanked the FDA for the grace period but insisted that the FDA’s tirzepatide decision is “not necessarily the end of the story.” APC CEO Scott Brunner highlighted the ongoing litigation in a statement, writing that the agency’s ruling was “not a decision by a court.”

“It’s a unilateral action by the agency, so don’t confuse the two,” Brunner said, adding that he anticipated the court would also consider the perspective of compounders. “Which is all to say: Stay tuned.”

“I’m just not persuaded that the data on which FDA is relying in this doubling-down on its shortage resolution decision is complete enough to say the shortage is really over,” Brunner said. “We continue to hear from pharmacies that the FDA-approved tirzepatide drugs are not attainable from wholesalers in quantities needed to meet demand by patients transitioning from compounded to commercial versions of the drug.”

In the FDA’s 12-page letter lifting the tirzepatide shortage, the agency asserted its authority to make its own decisions about shortages, responding to the compounder plaintiffs’ allegations that its process for resolving the shortage was a violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

“Making a determination regarding drug shortage status in a declaratory order issued as a product of informal adjudication is well within FDA’s discretion under the FD&C Act and the APA,” the letter stated. “Such applications of law to facts do not create new law and accordingly do not require FDA to engage in rulemaking, even if they include some amount of interpretation.”

According to Rosen, addressing the GLP-1 compounding situation is a priority for FDA staff and the letter reflects the FDA’s confidence in their position on tirzepatide.

The FDA also appeared undeterred in its work to decide whether the semaglutide shortage should be lifted. The same day the tirzepatide decision was released, the FDA posted that it “continues to actively monitor drug availability and is currently working to determine whether the demand or projected demand for each drug in shortage,” including semaglutide, “exceeds the available supply.”

An update in the back-and-forth between the FDA and compounder associations, which sued the FDA when they first lifted the shortage in October, is due later this week.

In a joint status report filed December 19, the FDA and plaintiffs asked the court to continue a stay of the litigation and pledged to provide an update on next steps in the case by this Thursday. The update will indicate whether the plaintiffs intend to pursue a preliminary injunction against the FDA. If successful, this could effectively extend the shortage on tirzepatide.

If the plaintiffs file their motion by January 2, the FDA has said it will continue to hold back on enforcement against the compounders for at least two weeks after the court decides on the potential preliminary injunction.

Rosen said it’s unlikely the compounders would prevail if they continued to pursue their lawsuit.

“I think it’s a long shot at this point. I do,” he said. “This is the first time I’ve ever seen anyone challenge the drug shortage decisions. And I just think that FDA has had their act together all along. I think what they were doing was just documenting the administrative record a little better and making sure that they were comfortable, because now with the change in the Chevron deference The June U.S. Supreme Court decision in Loper Bright overturned decades of precedent under the Chevron doctrine, which had instructed courts to defer to agency interpretations of statutory ambiguities. Without Chevron, courts have more leeway to decide whether the agency’s interpretation of law is proper. … they may have to have their ducks in a row a little bit more to make sure that they have a strong case.”

Rosen also said he doubts the FDA will give the tirzepatide lawsuit much weight in how it handles semaglutide. “I think they’re treating each product separately,” Rosen said. “Once they have confidence that Novo Nordisk can meet the market demands, I think that they’ll make their final decision.”

The plaintiffs alleged that FDA did not give enough weight to demand for compounded GLP-1s when it determined the tirzepatide shortage was resolved.

In its letter, the FDA explained that it considered information from compounders and other sources when reevaluating the tirzepatide decision but was ultimately not swayed by the data.

“We recognize that significant compounding of tirzepatide injection products is occurring, and that some number of patients currently receiving those products can be expected to seek Lilly’s approved products at a future point when compounding is curtailed. However, the additional information provided by patients, healthcare providers, and others, including compounders does not demonstrate that Lilly will be unable to meet projected demand, especially when weighed against the Lilly-provided data,” the letter reads.

According to the FDA, the difficulty in accessing branded GLP-1 drugs can be attributed not to an ongoing national supply shortage but rather to “the practical dynamics of the portion of the supply chain between Lilly and the individual customers, including wholesale distributors and retailers,” as Hunterbrook had previously reported.

“The fact of the matter is the law is on the FDA’s side,” said Chase, the former enforcement official at the FDA.

“The FDA rightfully admits there will be some people around the country who have trouble getting the drugs,” she said, “but it won’t be because the manufacturer isn’t making enough product.”

The shortage ending would be damaging — but not necessarily fatal — to the Hims GLP-1 business

As Hunterbrook reported on December 18, the resolution of the semaglutide shortage wouldn’t necessarily be the end of Hims GLP-1 business, but its future growth in the space could be hampered and will be dependent on regulatory outcomes.

Under sections 503A and 503B of the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act, there may continue to be specific, limited situations where compounding tirzepatide and semaglutide could take place, if a healthcare provider determines there is either a “significant difference” Section 503A(b)(2) of the FD&C Act provides an exception for “a drug product in which there is a change, made for an identified individual patient, which produces for that patient a significant difference, as determined by the prescribing practitioner, between the compounded drug and the comparable commercially available drug product.” or a “clinical difference” Section 503B(d)(2)(B) of the FD&C Act bars compounded drugs that are essentially copies of approved drugs “unless there is a change that produces for an individual patient a clinical difference, as determined by the prescribing practitioner, between the compounded drug and the comparable approved drug.” between the compounded version and the FDA-approved product.

In a November earnings call, Hims CEO and Co-Founder Andrew Dudum said the company would pursue this exception to continue selling customized compounded semaglutide after the shortage ends.

But this strategy could subject Hims to risk of enforcement by the FDA and legal action from Novo, which has already filed over 60 lawsuits against firms unlawfully marketing semaglutide products and vowed to keep pursuing legal action “against other entities engaged in similar conduct.”

When asked about its customized compounding approach, Hims directed Hunterbrook to information on its website about personalized healthcare, including an October white paper on the topic and a blog post highlighting their customers’ results with personalized weight loss products, as well as the Hims shareholder letter from Q3 2024.

Rosen is skeptical of Hims’ claim that customized dosing intended to mitigate side effects would qualify for this exception. “I don’t think that’s gonna fly, to be honest with you, all right. I think that the minor adjustments in the dose aren’t going to be enough to be clinically significant, in my mind, but I’m not the FDA,” he said.

The exception was intended to help a small subset of patients who are unable to take an FDA-approved product for a legitimate medical reason, like an allergy to a preservative or inactive ingredient. “But to say that there’s a clinical justification and rationale for something like that just so that everybody can have it, so you can get around the drug approval process, I don’t think that ultimately that’s going to be found to be acceptable to FDA at some point in time,” Rosen said.

Resolving the GLP-1 shortages won’t be the end of the FDA’s oversight of compounded weight loss drugs, according to Rosen. “I bet you that sooner or later … once the outsourcing facility situation gets done, either they’ll go after a couple of 503A compounding pharmacies who are compounding things, or they’ll send some warning letters out on the combination products and we’ll see what happens,” he said. “We just saw four or five warning letters that FDA sent out last week for ‘Research Use Only’ products that were represented with therapeutic claims.” On December 17, the FDA shared the warning letters it sent to Veronvy, Xcel Peptides, Swisschems, Summit Research and Prime Peptides for selling unapproved GLP-1s.

One wild card that may favor compounders is the nominee for FDA commissioner. As Hunterbrook reported on November 25, Dr. Marty Makary has worked as chief medical officer of a telehealth startup called Sesame, which also sells compounded GLP-1 weight-loss drugs online.

Hims is also exploring additional weight-loss products. In November, the company announced its intentions to begin selling generic liraglutide, another GLP-1 from Novo that’s been on the market since 2010, in the coming months. The FDA approved the first generic liraglutide from Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA on December 23. Liraglutide is also in shortage, which led the FDA to prioritize Hikma’s generic application, according to the agency’s press release.

Author

Laura Wadsten is a journalist based in Washington, D.C. She is also Executive Director of the nonprofit Moving to Value Alliance, where she produces and occasionally co-hosts the MTVA Unscripted Podcast. Previously, Laura wrote about antitrust and health care markets as a Correspondent for The Capitol Forum, a premium subscription financial publication.She was a Hodson Scholar at Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a B.A. in Medicine, Science & the Humanities.

Dhruv Patel also contributed reporting and data analysis.

Editor

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.