Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time.

Read the full report from The Independent Anti-Corruption Commission and the International Partnership for Human Rights, with support from Hunterbrook, here. Cover illustration by Maksym Filipenko

The woman was in her garden for 10 minutes, covering seedlings against the cold, when she heard the hum.

“I didn’t understand anything,” she later told investigators.

Then, the explosion, 30 feet away from her.

“When I came back to my senses a second later, I saw that there was nothing: the windows in the house were blown out, and the garage was destroyed. At first, I didn’t even understand what fell next to me. Everything that grew nearby was cut down like with a sickle.”

The next morning, she said, Russia had reportedly claimed to have hit military headquarters. “There were no military objects near us. It’s a residential neighbourhood,” she said, describing Hlukhiv, Sumy Oblast, Ukraine.

“We spent nine years building this house, with our money and energy. It’s so sad Russia destroyed all this in one moment.”

It was a Saturday morning. Maybe 200 shoppers were walking through the Epicentr hypermarket in Kharkiv — which is kind of like the Walmart of Ukraine. It’s a place where the whole family can shop for whatever they need: snacks and groceries, lighting and furniture, plants and gardening tools.

On May 25, 2024, it became the site of what legal experts described as a possible war crime.

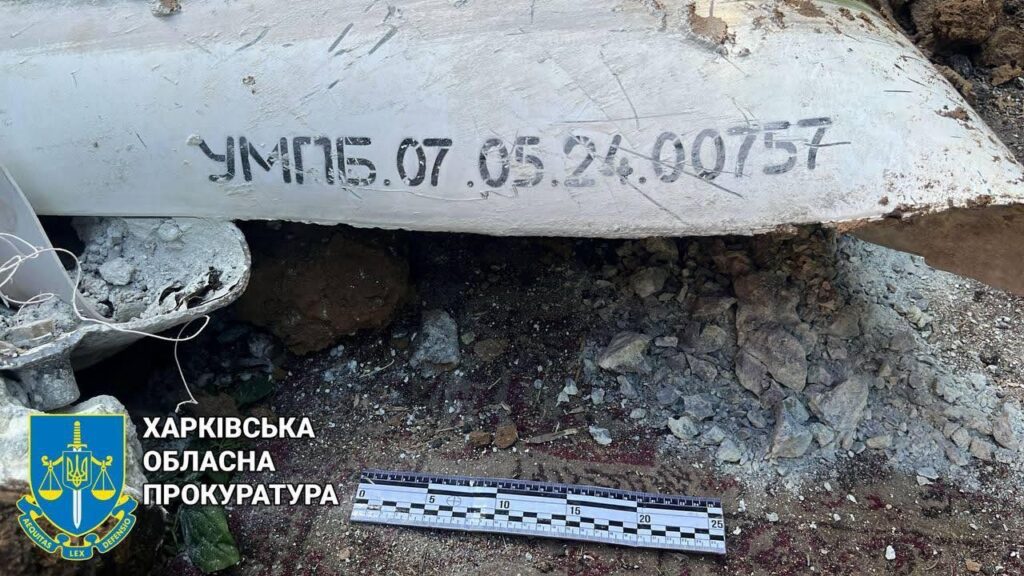

One UMPB D30-SN guided bomb struck the hardware department, another the gardening section, as local officials, journalists, and medical professionals posted online. A third, unexploded bomb landed 262 feet away, its casing stamped “07.05.24” — manufactured just 18 days earlier.

The attack reportedly killed 19 civilians, including six women and two children, while injuring 54 others. The fire consumed 140,000 square feet and took 16 hours to extinguish.

The weapons used in these and other attacks — KAB guided bombs, UMPB D30-SN bombs, and Grom-E1 cruise missiles, fired from Russian military aircraft — have accuracy ranges between 10 and 50 feet. They are designed to hit specific targets with minimal deviation, meaning that when they strike a grocery store or a hospital or a civilian community, that is likely precisely what Russia meant to do.

And these attacks are made possible not just by the bellicosity of the Russian military, but also by the sophistication of Western technology: microelectronics manufactured by household names like Intel ($INTC) and Texas Instruments ($TXN) are integrated into the targeting, navigation, and communications systems that guide Russian weapons to their targets.

This is the conclusion of a new investigation by the Independent Anti-Corruption Commission (NAKO) and the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR), with support from Hunterbrook Media. It is the third part in a series of reports on this issue — and the first that ties components to specific Russian attacks.

Over the last year, amid funding cuts to war crime investigations by the United States government, a team of investigative reporters and international lawyers traced the global supply chains feeding Russia’s war machine — analyzing more than 180,000 customs shipment records and identifying 141 Western companies whose components made their way into Russian military aircraft despite a labyrinth of international sanctions. The investigation’s central finding is that Russian Sukhoi Su-34 and Su-35S fighter jets The types of aircraft and weapons understood to have been used in the attacks were verified on the basis of official statements by the Ukrainian Armed Forces, the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, and local authorities. Russian sources and independent Ukrainian and international media sources were used to further corroborate the circumstances of the attacks. — the workhorses of Moscow’s precision-bombing campaigns — contain more than 1,100 microelectronic components manufactured across 11 Global Export Control Coalition countries. NAKO identified foreign components in Russian Su-34 and Su-35S jets and established manufacturers of those components, their respective jurisdictions, and the components’ export regulations. The identification of components had two stages. First, the Ukrainian military and governmental investigators conducted a preliminary identification by analysing remnants of downed Su-34 and Su-35S jets and data leaked from Russia. Then, NAKO used these preliminary findings to verify that the identified components exist and are on the market by finding them in online datasheets and marketplaces (e.g., DigiKey, Mouser, and so on). NAKO used information on the identified components from the online datasheets and marketplaces mentioned above to tie them to specific manufacturers and identify their head office jurisdictions. In several cases, the identified components were linked to regional offices of companies that produced them and not the head offices (e.g., the Swiss office of STMicroelectronics that is headquartered in the U.S.). More on this process in the full report.

The types of aircraft and weapons understood to have been used in the attacks were verified on the basis of official statements by the Ukrainian Armed Forces, the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, and local authorities. Russian sources and independent Ukrainian and international media sources were used to further corroborate the circumstances of the attacks.

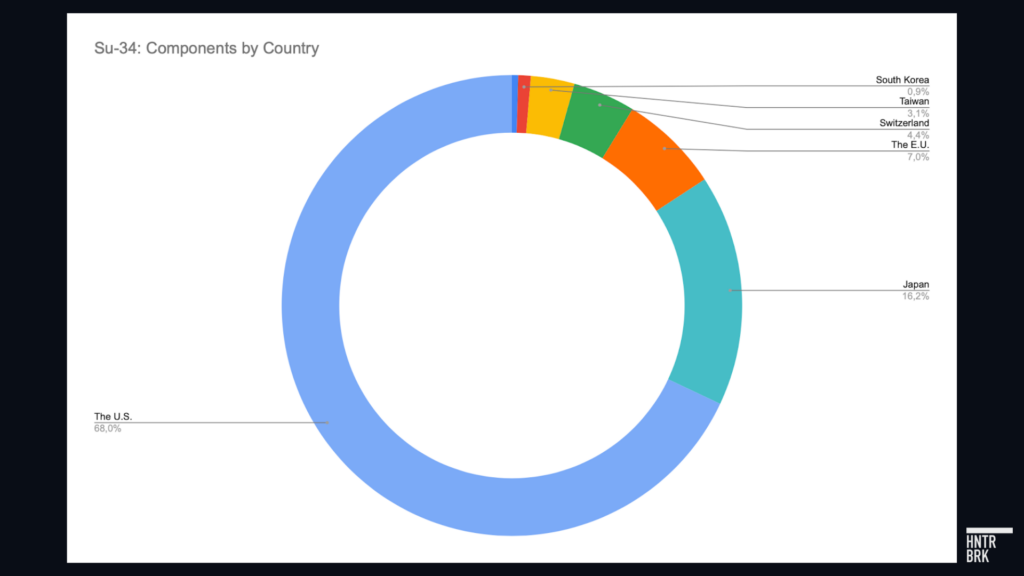

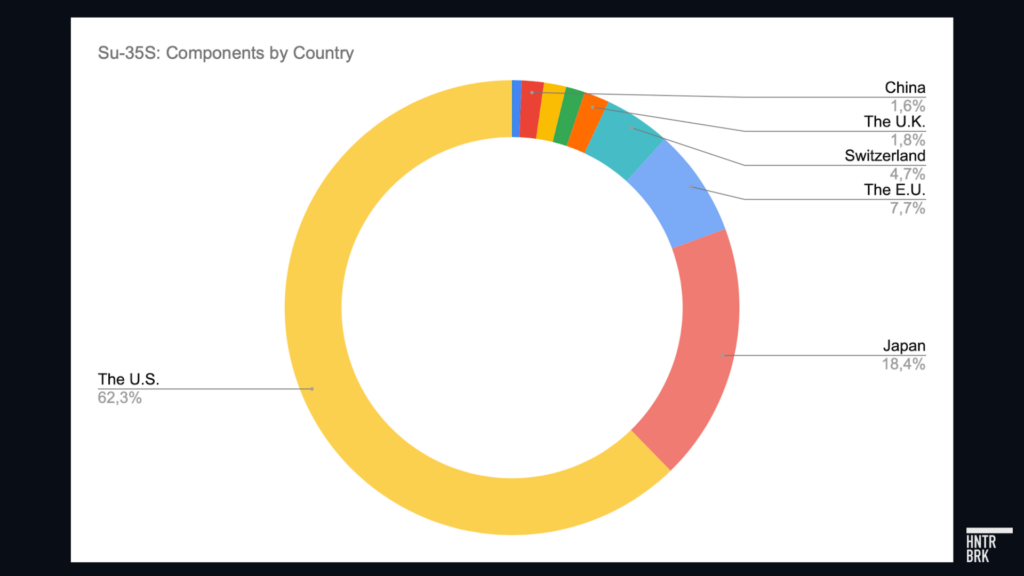

The United States provides the overwhelming majority, but the supply chain goes from Germany to Japan, creating a tapestry of Western complicity in the manufacturing of Russia’s most advanced military aircraft.

Exhibit 1: Origin of components found in Su-34

NAKO independently confirmed 227 out of the 228 components initially identified by military sources. These verified components trace back to 59 companies across eight countries, highlighting the prominent role of U.S. manufacturers in supplying electronic components used in Russian military aircraft production.

Exhibit 2: Origin of components found in the Su-35S

Of the 891 total components sourced from 138 different companies, 58.9% fall under stricter export control regulations, marking them as high-priority items for oversight. While the United States is again the primary foreign supplier, the Su-35S aircraft notably incorporates components from a broader international range compared to the Su-34: Germany, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the U.K., Bulgaria, Belarus, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Israel.

“Russia mastered the art of circumventing sanctions,” said Anastasiya Donets, who runs the Ukrainian legal team at IPHR. “They are still getting Western tech in Russian weapons that are killing Ukrainians every day.”

The investigation focused on what the authors think of as 10 possible war crimes — precision strikes on hospitals, schools, and shopping areas. In each case, the authors geolocated the impact sites, established the weapons used and their accuracy ranges, and ruled out the possibility of the presence of potential military targets in the vicinity of struck objects.

“The ten selected attacks resulted in 26 civilian deaths and 109 injuries,” reads the report. “In five of the ten attacks, children were among the victims. The attacks caused large-scale destruction or damage to civilian infrastructure, including at least 71 civilian houses and apartment buildings, The report concluded, “This is a conservative estimate based on official damage reports that specify the number of affected civilian homes. In four cases with reported damage/destruction to civilian homes, the exact number of affected objects is unknown and was not included in the estimate. Therefore, the real number of destroyed/damaged civilian homes is likely much higher. five schools, five medical facilities, and three energy infrastructure facilities.”

The Technological Sinews of War

Inside the cockpits and avionics bays of the Russian aircraft conducting these strikes, investigators dug up evidence that reveals the global networks sustaining Moscow’s military capabilities. The report found that the Su-34 alone contained 227 verified foreign components from 59 companies across eight countries. The Su-35S, which protects fighter bombers such as the Su-34 on the battlefield, held 891 components from 138 companies spanning an even broader geographic range.

These are not generic parts but technology like semiconductors that form the nervous system of modern military aviation. “The list of microelectronics includes integrated circuits (ICs), capacitors and transistors, field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), which are crucial for reconfigurable computing tasks, and specialised microcontrollers and digital signal processors,” reads the report.

The components identified most frequently came from industry giants: 102 from Analog Devices, 123 from Murata, and 120 from Texas Instruments, according to the report. But the supplier list reads like a who’s who of global technology, including Intel, AMD, Maxim, OnSemi, and Vicor. Each component serves a critical function in the aircraft’s advanced functionality, enabling precise targeting, communications, and navigation systems.

Some of these companies, including Analog Devices, Intel, Texas Instruments, and AMD, came under scrutiny during a hearing held last year by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, titled The U.S. Companies’ Technology Fueling the Russian War Machine. The Senate committee presented evidence that components from these companies were found in the Russian Kh-101 cruise missile that struck Ukraine’s largest children’s hospital in 2024. Senators also highlighted significant gaps in these companies’ export control and compliance processes, notably delays in identifying suspicious entities, inadequate responses to external warnings, insufficient use of advanced analytics for due diligence, and a lack of routine audits.

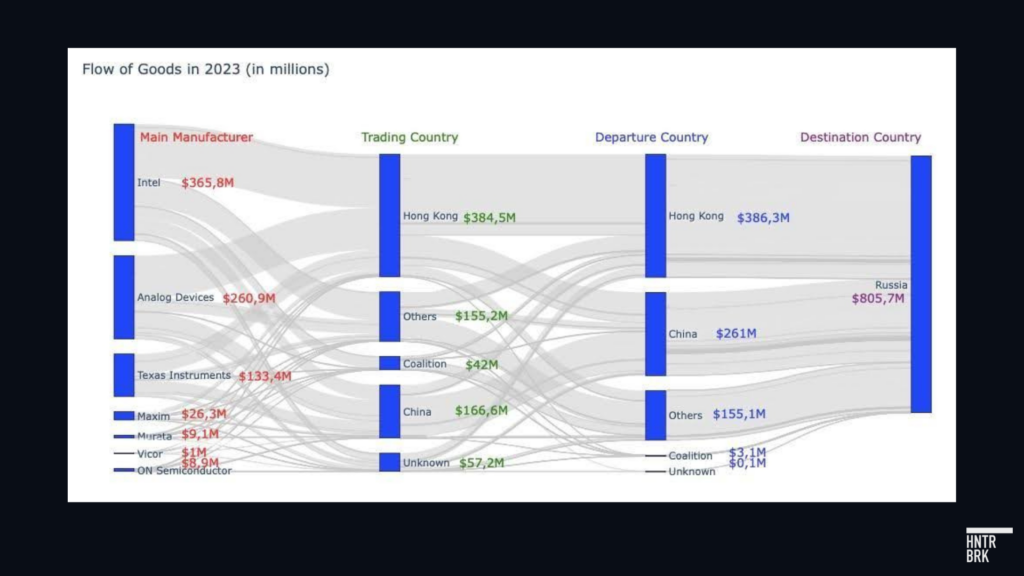

The $805 Million Pipeline

Despite heavy international sanctions, the flow of Western semiconductors to Russia continues on an industrial scale. The investigation’s analysis of more than 180,000 customs shipment records from 2023 The supply chain analysis covers over 180,000 shipments of the prioritized microelectronic goods produced by leading manufacturing companies such as Intel, Analog Devices, and Texas Instruments in 2023. The list of such prioritized microelectronics includes ceramic capacitors, processors, controllers, memory, and electronic integrated circuits. Their imports are crucial for the Russian military industry. reveals a trade worth approximately $805.6 million in microelectronic goods from leading Western manufacturers.

Countries like Serbia exemplify the complex supply chain choreography required to pull this off. Of $50.9 million in transactions, $21.8 million worth of goods allegedly originating in Serbia actually arrived in Russia from Hong Kong and $21.3 million allegedly came from Sri Lanka. Thirteen ostensibly Serbian companies facilitated these transfers, but the components entered Russia from countries thousands of miles away. Serbia, the third-largest country of trade, ensured the financial support for contracts worth at least $50 million. Thirteen of 26 supplier entities are Serbian and make up the majority of the supply: Aktechnology Doo, Conex Doo, Goodforwarding Doo, Kominvex Doo, Lasopsys Doo, Logimix Doo, Metalik Kroj Doo, MKKK Doo, New Case Doo, Research & Development Co Tr Industries Doo, Soha Info Doo, TTS Logistics Doo, and Uspon Doo. The imports, however, mostly came through countries of dispatch in Asia, predominantly from Hong Kong ($21.8 million) and Sri Lanka ($21.3 million).

The intermediary companies themselves range from legitimate businesses to entities that openly advertise sanctions evasion. One company, based in Saint Petersburg, publicly promoted its expertise in “parallel imports” of sanctioned goods through “partners from Turkey, Europe, the UAE, Serbia, and Armenia,” according to what the report’s authors claim was an old version of its website. The company’s website allegedly described its work as “an exciting game, in which we constantly overcome the obstacles, while the level of difficulty increases.”

More troubling are the direct connections to the Russian military industry. As NAKO reported in 2024, for example, customs data reveals that the Ural Optical-Mechanical Plant, a part of Shvabe Holding within state defense conglomerate Rostec that produces bomb aiming systems and laser guidance equipment for military aircraft, received more than $370,000 worth of microelectronics from Texas Instruments, Analog Devices, Intel, and other Western manufacturers through Shvabe’s Chinese subsidiary.

Corporate Excuses

In summer 2024 and spring 2025, IPHR, NAKO, and Hunterbrook conducted two rounds of outreach to 143 companies whose components were found in Russian Su-34 and Si-35S military jets that conducted attacks in Ukraine, which possibly amounted to war crimes. We asked these companies about their awareness of their products’ integration into Russian military jets and their response to such use.

When confronted with evidence of their technology’s role in Russian war crimes, Western manufacturers offered responses ranging from genuine concern to corporate stonewalling. Forty-four companies responded.

Of these, 11 manufacturers went beyond standard compliance statements, outlining three main ways in which Western technology arrives in Russian military systems: legacy inventory shipped before the invasion, counterfeit or relabeled parts, and indirect distributor chains outside the companies’ control.

Legacy inventory emerged as the most common explanation. Peak Electronics traced a converter found in Su-35S wreckage to a model discontinued in 2006. ITT noted that its microswitch was produced only between 2000 and 2007 but has an essentially indefinite shelf life. NEC pointed out that its LCD module left the supply chain no later than 2011. These findings reveal a fundamental challenge: Electronic components can remain dormant for years or decades before resurfacing in active military systems.

Some companies responded robustly. Analog Devices described a comprehensive export control program including quarterly reviews, a “red-flag process,” and a Grey Market Mitigation Team that blocked $66 million in suspicious sales during fiscal year 2023.

Others were less forthcoming. Texas Instruments provided only a general statement: “Texas Instruments (TI) strongly opposes the use of our chips in Russian military equipment and the illicit diversion of our products to Russia. TI stopped selling products into Russia and Belarus in February 2022. Any shipments of TI chips into Russia are illicit and unauthorized.”

The company did not address specific questions about compliance measures, supply chain oversight, or how its 120 identified components reached Russian aircraft. This is particularly significant given that a U.S. Senate investigation found that Texas Instruments had failed to respond to over 100 trace requests from external investigators between August 2022 and February 2024 concerning the presence of their components in Russian weaponry used in Ukraine.

Murata Manufacturing, whose 123 components represented the largest category the investigation found in Russian aircraft, acknowledged it was aware of media reports about its products’ possible military use but stated it was “unclear whether the products in Russian military jets are actually manufactured by Murata.” The company emphasized its policy “prohibiting the use of our products for military purposes” but offered no explanation for how its components reached Russian weapons systems.

War Crimes?

“In all cases included in this report, Russian forces directed attacks against the civilian population or individual civilians not taking part in hostilities,” the report concluded, arguing that the attacks constituted war crimes under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, to which Ukraine is a party, based on the precision of the weapons, the civilian targets, and the absence of military objectives within the accuracy range of the munitions.

“They were targeting not only civilian buildings and densely populated civilian areas, they targeted places with special protections under international humanitarian law — schools and hospitals,” said Donets.

This conclusion is reinforced by the technical specifications of the weapons themselves. UMPB D30-SN bombs, first deployed in March 2024, represent Russia’s effort to create lower-cost precision weapons with longer strike ranges. With an accuracy range estimated at 15 to 30 feet, and equipped with GLONASS navigation systems, they enable attacks from inside Russian territory against Ukrainian border regions.

According to experts from the State Aviation Research Institute (Kyiv) and the State Research Institute for Testing and Certification of Weapons and Military Equipment (Cherkasy), as of 2025, Ukraine still lacks the capability to effectively intercept UMPB D30-SN bombs. That’s, in part, because Russian jets Su-34 and Su-35 deploy these bombs while remaining beyond the reach of Ukrainian air defense systems. Ukrainian and international weapons experts describe them as Russian analogues to American GBU-39 Small Diameter Bombs, which have an accuracy range of about 10 to 25 feet.

Russian military social media posts around the time of the attacks further suggest civilians were deliberately targeted. On the day of the May 22, 2024, attacks in Kharkiv, a pro-Russian blogger published photos of UMPB D30-SN bombs attached to a Su-34 aircraft, along with cockpit video While two bombs from the video are likely to be the ones used in the attacks on the Shevchenkivskyi and Kholodnohirskyi districts, there is no information available about the third bomb. Given that these bombs are launched from Russian territory, are still under development, and are reportedly prone to failure, it can be presumed that the third bomb malfunctioned and did not reach Ukrainian territory. See: Foundation for showing their launch. One bomb bore the inscription “Greetings from Belgorod! 22.05.24″— the exact date and location of the Su-34 bomb strike confirmed by Ukrainian prosecutors. Another bomb carried a message urging viewers to subscribe to the pro-Russian blogger’s channel.

A 19-second video from the perspective of a Su-34 pilot shows UMPB D30-SN bombs being dropped, their wings deploying as they glide toward their targets — headed toward the entrance of a café in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city. The attack reportedly injured 12 civilians, including a 16-year-old.

To Donets, an international lawyer, these attacks are “clear-cut cases of war crimes” — and she said the Western companies whose components contribute to these precision attacks have “not only legal, but also a moral obligation” to do everything possible to ensure their technology is not used in Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.

For now, the U.S. government appears to be going in a different direction. In June, Reuters reported that the White House is thinking about terminating funding for “nearly two dozen programs that conduct war crimes and accountability work globally.”

Among the planned cuts, according to Reuters, are war crime accountability programs in Ukraine.

This comes amid an onslaught of relentless attacks on Ukraine over the summer — with reports that the United States has halted shipments of missile defense systems.

Author

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Other authors contributed to the article. They prefer to remain anonymous — for fear of retaliation.

Editor

Wendy Nardi joined Hunterbrook after working as a developmental and copy editor for academic publishers, government agencies, Fortune 500 companies, and international scholars. She has been a researcher and writer for documentary series and a regular contributor to The Boston Globe. Her other publications range from magazine features to fiction in literary journals. She has an MA in Philosophy from Columbia University and a BA in English from the University of Virginia.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.