Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is long $LQDA at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

Drug development is tightly regulated, designed to strike a balance between incentivizing innovation and ensuring access to affordable treatments. Today, a federal judge in Washington, D.C., will consider whether the regulator tasked with overseeing that balance has overstepped, tipping the scales in favor of Big Pharma.

Liquidia Planned to Begin Offering Patients a New Treatment in August

The medicine had proven safe and effective. The developer was ready to launch across the U.S. Dozens of salespeople at Liquidia Corp. (NASDAQ: $LQDA) were primed to market its new product. Yutrepia is an inhaler version of a drug called treprostinil that treats two severe lung conditions in markets worth billions of dollars: pulmonary arterial hypertension, known as PAH, and pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease, known as PH-ILD. Interstitial lung disease is a term encompassing over 200 different conditions that cause scarring and inflammation in the lungs.

“Breathing for us is kind of like breathing through a straw,” a patient named Lynette Chambers told Hunterbrook, describing a life where walking up the stairs or taking a shower can lead to extreme fatigue. Liquidia has waited over four years for the FDA to let it bring Yutrepia — a drug potentially worth billions that could delay disease progression and prolong lives — to patients, fighting against attempts to block its approval by rival United Therapeutics Corp. (NASDAQ: $UTHR), where Liquidia’s CEO used to work.

Yutrepia’s approval would end UTC’s exclusivity over the treatment — a monopoly so lucrative that it has been the major contributor to the company’s reaching a market cap of more than $16 billion, to say nothing of its building a 35,683 foot hangar at Concord Municipal Airport, rumored to house UTC’s helicopters, Gulfstream, and turboprop planes. (The company shields its ownership of its fleet using a trust service.)

In 2023 alone, UTC generated $1.23 billion in revenue from the two therapies that Yutrepia would directly compete with.

Experts told Hunterbrook that bringing Liquidia’s product to market could lead to savings for thousands of patients suffering from incurable lung disease. In its own court filings, UTC has shared a similar perspective, citing the “risk” that the new drug coming to market could lead to “permanent price erosion.”

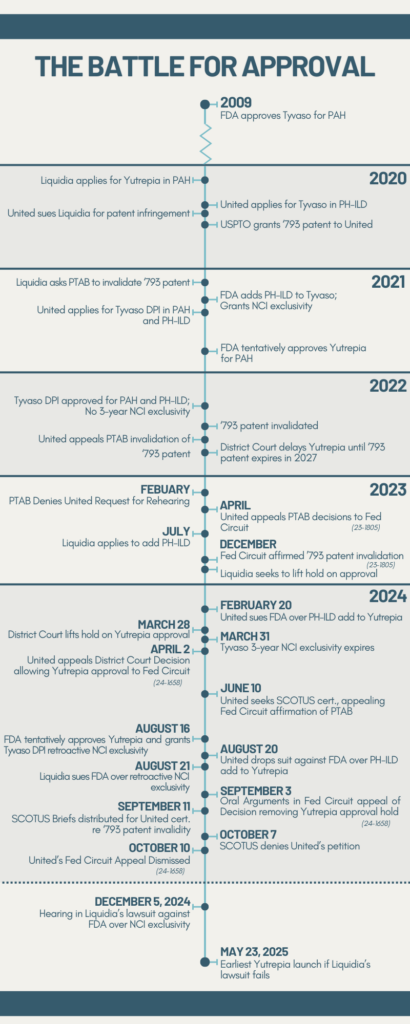

Timeline of Liquidia’s Battle for Approval of Yutrepia

The FDA’s Sudden Reversal

On the eve of Yutrepia’s anticipated launch in August 2024, Liquidia faced an unprecedented surprise.

Having knocked out the patents and waited out the initial regulatory exclusivity blocking its entry, Liquidia expected the FDA to grant final approval to Yutrepia. Instead, the agency afforded retroactive exclusivity to a competing product developed by UTC.

UTC had been suing the FDA since February for allowing Liquidia to add treatment of PH-ILD to its Yutrepia application for PAH. Two lawyers Hunterbrook spoke to speculated that, under the pressure of this lawsuit, the FDA scrambled to find a middle ground in the Liquidia-UTC rivalry — landing on awarding a late exclusivity to UTC.

Suddenly, Yutrepia couldn’t launch until May 2025. Liquidia’s stock fell over 30% within minutes, losing over $330 million in market cap that day.

Stand down, Liquidia told its new sales team, which suddenly had nothing to market. The company had spent millions of dollars on inventory that would now expire and go to waste.

It was the latest in a long line of wins for UTC, whose stranglehold over the treprostinil market persists despite the original patent on the active ingredient expiring over 20 years ago. UTC’s stock leaped over 8% — gaining more than a billion in market cap — the day news broke of the delayed Yutrepia launch.

Then Liquidia sued the FDA, accusing it of improperly flip-flopping in favor of UTC without explanation.

In a memo filed August 27 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Liquidia contended the FDA’s about-face unfairly blocks Yutrepia from reaching patients, despite the company being “the first to conduct a clinical study with a dry powder treprostinil formulation, the first to submit such a formulation for FDA approval, and the sponsor of the first dry powder treprostinil formulation found by FDA to be a safe and effective drug warranting approval.” This afternoon, Judge Timothy J. Kelly will hear arguments in the case to help him determine whether Liquidia can launch earlier than May.

UTC Uses Every Tool Available to Delay Yutrepia

Despite Liquidia being the first to develop and apply for FDA approval of a dry powder inhaler formulation of treprostinil, UTC — a much larger company with decades of market dominance — managed to secure approval for its Tyvaso DPI first, in part by purchasing a $105 million priority review voucher. Priority review vouchers shorten the timeline of FDA review from 10 months to 6 months, as incentives to develop drugs for specific priority conditions. The vouchers can be redeemed for any drug application and can be sold to other drugmakers, often for hundreds of millions of dollars. .

When Liquidia submitted its application for Yutrepia to the FDA in 2020, UTC sued Liquidia for patent infringement — triggering a statutory hold

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, also known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, allows applicants to rely on studies completed for previously-approved products. Companies seeking FDA approval under these abbreviated pathways must submit certifications about all patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book for the existing product they rely on. If a company wants approval before patents on the existing drug expire, they submit a “paragraph IV certification” — attesting that the patents are “invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the … product.” If the patent holder sues the applicant within 45 days of the paragraph IV certification, it triggers an automatic stay that prevents FDA from approving the application for 30 months or until the patent litigation is resolved.

on FDA approval of Yutrepia. Initially, UTC succeeded on the basis of one patent, securing a final judgment that blocked Liquidia from approval until the patent’s expiration in 2027.

But Liquidia managed to get this patent thrown out by the U.S. Patent Trial and Appeal Board. In January 2021, Liquidia challenged the validity of UTC’s ‘793 patent before the PTAB through a process called Inter Partes Review. The PTAB sided with Liquidia in July 2022, finding all claims of the ‘793 patent invalid. A month later UTC requested a rehearing, which the PTAB denied in February 2023. UTC appealed in April 2023 to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the PTAB decision in December 2023. UTC appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2024, which declined to hear the case in October. In March, the judgment barring Yutrepia’s approval was vacated.

After four years of litigation, it seemed like Liquidia had finally prevailed — until the FDA’s August decision extending UTC’s exclusivity.

In parallel, the FDA gave Liquidia an unexpected “tentative” approval, finding that Yutrepia is safe and effective in treating PAH and PH-ILD but cannot launch until May 2025, when Tyvaso DPI’s retroactive exclusivity expires.

It was a major win for UTC, which has strategically released new formulations of treprostinil since acquiring the rights to it in 1999, extending its exclusivity. UTC has taken advantage of FDA guidelines awarding “orphan drugs” that target rare diseases with seven years of exclusivity. Companies can unlock another three years of exclusivity if they conduct a “new clinical investigation” that reveals significant new information about an existing drug. These incentives and a “patent thicket” helped UTC build a wall defending its blockbuster franchise.

UTC has also taken more creative approaches to keeping alternatives to its treatments off the shelves.

But even after all these successes, the August win over Liquidia stands out — for two reasons:

1) Normally, the FDA makes exclusivity determinations when a drug is approved, not two years after a product hits the market; and

2) When the FDA approved UTC’s drug in May 2022, the clinical review staff did not think its study deserved NCI exclusivity, according to the agency’s “Exclusivity Summary” from the time, released in response to a FOIA request by a law firm representing Liquidia.

UTC has close ties to the FDA, with two board members who each led the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA’s parent agency. Louis Sullivan was HHS secretary from 1989-1993 under George H.W. Bush; Tommy Thompson was HHS secretary from 2001-2005 under George W. Bush.

Experts told Hunterbrook that the dispute between Liquidia and UTC exemplifies broader issues with the current legal and regulatory framework around the drug market.

While the specific issue in Liquidia’s lawsuit is whether the FDA is applying the regulations and statutes in a way that fulfills its obligations, Rebecca Wolitz, an assistant professor of law at The Ohio State University, said this case also raises a larger question: Are the results we’re seeing from the existing framework for exclusivities serving the public interest?

Sean Tu, a West Virginia University law professor focused on patent and drug law, said that the problem is a mismatch between incentives like exclusivity and the value of the innovations they reward. “Part of the problem is we’re not paying for the incremental innovation. We’re paying for the entire innovation, or we’re treating the incremental innovation as if it was a new molecular entity, and that’s a problem,” Tu said.

The Stakes: Patient Lives and Billions in Revenue

The tortured launch episode reveals the protracted legal wrangling that can keep drugs off the shelves and pharmaceutical prices out of reach. About one in every hundred people in the world suffers from pulmonary hypertension, a diagnostic category that includes PAH and PH-ILD, among other illnesses. Pulmonary hypertension is an incurable condition that causes the heart to struggle to circulate blood through the lungs for oxygen. After time, overwork strains the heart muscle, in some cases causing it to fail.

Chambers said she was first diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension nine years ago. This spring, she was also diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis — a type of interstitial lung disease.

Her symptoms started as shortness of breath, a symptom that defines most patients’ experiences with pulmonary hypertension. This made it hard to walk; after getting home from work, she struggled to make it up the sidewalk from her car into her home.

“I would go up four stairs, and I would have to sit down there before I could make it through to go into the house. And then I would have to sit down on my couch and try and fully recuperate. I just couldn’t get a full breath in,” Chambers told Hunterbrook. “It was like there was a shelf that you go to breathe, and it just kind of stops at that shelf and says, ‘No, you can’t have any more.’ So I wasn’t getting a full breath in, and I was getting to a point where I was really scared.”

Her shortness of breath got worse, and when she saw a doctor: “I sat down in the waiting room, and thankfully, you know, you’re generally in there for a little bit before the doctor sees you. Then by the time I walked from the waiting room into the doctor’s office, I couldn’t breathe again.”

After a plethora of tests, Chambers was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, and told she had just two to five years to live. She refused to accept this “expiration date” and has been fortunate to far surpass it. She said she is still able to live her life — she continues to work and spend as much time as possible with her family — things just look a bit different. Chambers has not tried inhaled treprostinil (which isn’t approved in Canada, where she lives) and doesn’t recall having ever taken any form of treprostinil. She takes medications for other medical conditions, including two inhalers that help with her breathing difficulty symptoms (though they’re not specifically approved as PH-ILD treatments), and her medical team is monitoring the progression of her PH and pulmonary fibrosis.

“Stairs are not a good friend of mine,” she said. “Things like having a shower take everything out of you, and you know that you’re not going to be able to breathe well through it.” Chambers and her husband are also considering selling their split-level house, so she doesn’t have to deal with as many stairs.

“It’s like having a glass of water and only having access to half of it,” she said, describing her disease. “You know that your lungs have more, you just can’t get it.”

In the U.S., about half of PAH patients and one-third of PH-ILD patients die within five years. Treating PH-ILD is particularly challenging due to the lack of options: UTC’s Tyvaso — inhaled treprostinil taken via nebulizer — and Tyvaso DPI, aka dry powder inhaler, are the only products currently approved.

They aren’t cures, but they are invaluable to patients who rely on them to live their lives.

The drugs are also, of course, quite valuable to UTC.

Tyvaso DPI has quickly become UTC’s most lucrative product. In Q3 2024, Tyvaso DPI alone brought in $274.6 million — accounting for 36.67% of the company’s total worldwide revenue that quarter. Liquidia CFO and COO Michael Kaseta told investors PH-ILD has an addressable market of 60,000 patients to 100,000 patients at a September 2024 Conference

Tu told Hunterbrook that based on UTC’s 2023 financials, one single day of exclusivity is worth millions to the company.

“Of course they would be incentivized to get even a week of added exclusivity,” Tu said. “How much does litigation cost? On the expensive end, maybe, like, five or six million.”

“If I delay it a week, that’s $30 million. If I delay it a day, it’s $3 million,” Tu said. “That’s real money.”

“The litigation has paid for itself, and then 10 times over, probably.”

BTIG estimated that the total market for treprostinil dry powder inhalable in PAH and PH-ILD “is estimated to be in excess of $3B at maturity,” referring to the value in a single year of peak sales.

Liquidia expects the PH-ILD market alone could be worth between $2 billion and $4 billion, with Chief Operating Officer and Chief Financial Officer Michael Kaseta stating the company is “very bullish” on Yutrepia at a September investor conference. The company projects it will reach profitability within three or four quarters after launching the product.

Liquidia sues FDA for penalizing the “true innovator”

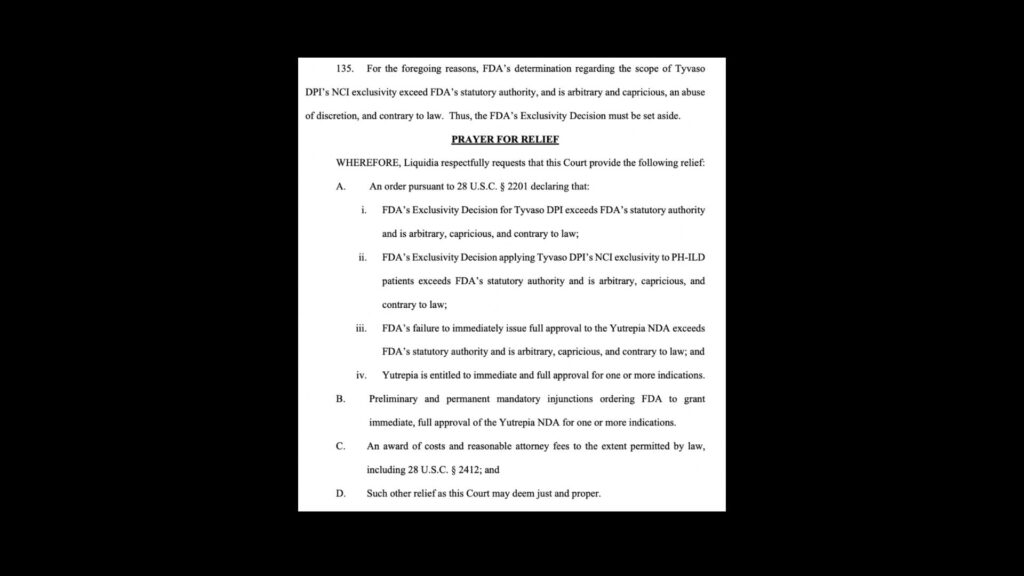

Liquidia argued that the FDA’s decision to grant UTC exclusivity for Tyvaso DPI was unlawful and improperly delays Liquidia from bringing Yutrepia to patients.

“UTC is being rewarded for copying Liquidia’s innovation and then slowing approval for Liquidia’s drug through meritless patent litigation, not any actual innovation by UTC. Meanwhile the true innovator, Liquidia, is penalized,” Liquidia’s filing stated.

Liquidia asked the court to kill the NCI exclusivity — or at minimum narrow its scope — and require that the FDA let Yutrepia launch immediately. UTC promptly intervened.

Though Judge Kelly could rule from the bench at today’s hearing, Liquidia executive Kaseta told investors at the September conference that they expect Kelly will issue his opinion a month or two after the hearing.

The FDA defended the new NCI exclusivity as proper and its scope as reasonable in its response filing. Contacted by Hunterbrook, the agency noted its policy of not commenting on litigation.

A spokesperson for Liquidia directed Hunterbrook to its press release announcing the litigation:

“The FDA’s action improperly allows United Therapeutics to tack on yet another regulatory exclusivity, stifling competition and patient choice,” Liquidia CEO Roger Jeffs stated. “It is our strong belief that the FDA’s decision to grant Tyvaso DPI this new NCI exclusivity should be vacated, and Liquidia should be allowed to bring YUTREPIA to market for the benefit of patients immediately.”

Jeffs joined Liquidia after working for 18 years at UTC, departing as president and co-CEO in 2016.

UTC declined Hunterbrook’s request for comment.

FDA Denies Changing Its Mind, but Administrative Record and Timing of Decision Suggest Otherwise

Granting an exclusivity this late after approval is rare.

A lawyer specializing in FDA matters who spoke to Hunterbrook on condition of anonymity said that about “97% of the time these things go in the Orange Book within a month of approval.” The Orange Book is where the FDA publishes its exclusivity decisions, as well as a list of relevant patents protecting existing drugs.

And the timing of these decisions is critically important, because companies base their product development and launch strategies on information in the Orange Book.

“It’s broadcasting to the world when people can go after these drug products, so it’s not insignificant when they make those determinations,” William Garvin told Hunterbrook. Garvin is co-chair of Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney PC’s FDA and biotechnology law practice.

The anonymous lawyer with FDA expertise echoed Garvin’s concerns about the FDA’s decision to grant exclusivity so late.

“You’re a competitor, and you’re having to make decisions about, you know, building out a sales force, and you’re advising investors,” the lawyer said, referring to Liquidia’s predicament. ”For two years, this competitor product has been approved with no exclusivity, and then all of a sudden, it kind of falls on you.” There’s a “certain lack of fairness, I think, in the delayed decision.”

Yet, according to the FDA, the August exclusivity decision isn’t even a reversal, but rather the agency’s “first and only determination” regarding Tyvaso DPI’s eligibility for exclusivity. The original exclusivity summary was just a recommendation from one component of the agency, according to the FDA’s October 23 legal brief.

The FDA’s stance that it hasn’t reversed course from an earlier exclusivity determination is a tough sell, according to Garvin.

“It looks like they approved something in 2022 and had a certain exclusivity determination, and now they’ve decided to say, ‘No, that was not our final determination, this now is our final determination’ in August,” Garvin told Hunterbrook. “This is the first time I’ve heard of the idea that you don’t really have exclusivity once you’re approved, you’ve got to wait until some later time when there’s a final determination.”

The agency’s handling of the exclusivity determinations also undermines this idea, Liquidia argued in an October 30 reply brief. The FDA itself called the 2022 and 2024 review documents the “Original” and “Superseding” exclusivity summaries, respectively. “If an earlier exclusivity decision were never made in the first place, it cannot be ‘supersed[ed],’” Liquidia stated in the reply brief.

In its reply brief, Liquidia also pointed to the fact that the FDA released the “Original exclusivity summary” in response to a FOIA request in August 2022. If the earlier document was, indeed, a predecisional assessment, the agency would have been exempt from releasing it. Liquidia claims the FDA could have relied on an exemption under the Freedom of Information Act called “deliberative process privilege” at 5 U.S.C.§ 552(b)(5). FDA regulations outline this exemption at 21 CFR 20.62.

The FDA refuted Liquidia’s characterization, arguing that it had waited to make an exclusivity decision for Tyvaso DPI “until 2024, when the agency needed to determine whether any such exclusivity would block approval of Yutrepia.”

For Garvin, whether the FDA’s August 2024 decision was a reversal will be a key question for the court.

“When does the FDA make determinations on exclusivity? Is it at the time that it’s actually approved, or can FDA come around later and say, ‘Well, actually, since there was no real challenge, it didn’t change anything for our approval, the only time when we actually know whether something has exclusivity is when there’s an actual determination about whether it’s blocking a product or not,’” Garvin asked. “Is that what Congress intended with determinations of exclusivity?”

Court Will Review FDA’s Decisionmaking Process and Application of Statutes, and the Value of UTC’s Study

When seeking FDA approval for a product that uses an existing active ingredient in a new way, applicants can rely on the safety and efficacy of previously approved products and submit “bridging studies” to show how their new medication compares to the existing “reference” product. Both UTC and Liquidia took advantage of this for their treprostinil dry powder inhaler applications: nebulized Tyvaso is the reference drug for both Tyvaso DPI and Yutrepia.

UTC submitted three bridging studies The three bridging studies submitted with UTC’s application for Tyvaso DPI were TIP-PH-101 (AKA BREEZE), TIP-PH-102, and MKC-475-001. for Tyvaso DPI; one of these, the BREEZE study, was determined to qualify for NCI exclusivity by the FDA. BREEZE was a small, short-term clinical trial that followed 51 patients with PAH who switched from nebulized Tyvaso to Tyvaso DPI over just three weeks. It did not include any PH-ILD patients, nor did it study any patients who were not already taking nebulized Tyvaso.

Liquidia has argued that the BREEZE study used to justify UTC’s new exclusivity does not meet statutory requirements, and that the FDA’s decision to award it over two years after approving Tyvaso DPI constitutes an improper reversal by the agency, in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

Not everyone is convinced the court will see it that way.

“I’ve done this for 31 years. More times than not, if the company asks for exclusivity, and there’s a basis for it, FDA gives it to them, because it encourages innovation,” Alan Minsk, a lawyer who specializes in life sciences and FDA matters, told Hunterbrook. “It’s a judgment call by the FDA.”

Minsk is chair of Arnall Golden Gregory LLP’s food and drug practice. He does not advise either company on this issue.

Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, a “new clinical investigation” must be a study in humans that was “essential to the approval” of the drug. And it only includes “investigations (other than bioavailability studies).” 21 USC §355(c)(3)(E)(iii). See also 21 CFR 314.108(b)(4)(iv) and 21 CFR 314.108(a)

This means only trials designed to demonstrate the safety or efficacy of the drug in humans are eligible. Studies that merely show how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted by the body are not considered for this exclusivity.

Liquidia claimed the BREEZE study yielded no new clinically significant insights and was merely a bioavailability study. At first, the FDA seemed to agree. The original exclusivity summary from the time of approval stated that, “The safety and tolerability study provided confirmatory efficacy information only,” and indicated “NO” to whether the application contains reports of clinical investigations “conducted on humans other than bioavailability studies.”

Interestingly, the FDA exclusivity summary form includes a note that, “Studies comparing two products with the same ingredient(s) are considered to be bioavailability studies.” BREEZE undeniably matches this description: The study is a before-and-after comparison of 51 patients who switched from Tyvaso nebulizer to Tyvaso DPI.

But in the August letter to Liquidia, the agency took the position that BREEZE was not “solely a bioavailability study.”

Liquidia also argued that the exclusivity awarded is too broad for the BREEZE study’s findings. In its reply memorandum, the FDA defended the scope of exclusivity by asserting that a clinical investigation can yield insights beyond the specific bounds of what it studied.

The agency argued that it “is especially suited to determine what conclusions can be extrapolated from the BREEZE study results, and its conclusions are entitled to deference.”

It will ultimately be up to the court to decide whether the August exclusivity award was, in fact, the FDA’s first and only decision — or if it was an “arbitrary and capricious” reversal in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

The APA allows courts to review agency actions and set aside an unlawful decision or compel the agency to take an action it unlawfully withheld. If Judge Kelly determines the FDA did violate the APA in reversing its original exclusivity determination, it could order the agency to reconsider its decision.

For Charles Duan, an assistant professor at American University who specializes in intellectual property law, the case boils down to whether a study like the one UTC conducted is worth the value of three years of exclusivity to a drugmaker.

“The story that Liquidia wants to tell here is this is just a very half-baked study, and look how much exclusivity and how much value you’re giving them for it. And to the extent that you can get that exclusivity from a very, very cheap study, what sort of incentives are you giving people?” Duan told Hunterbrook. “You’re just telling people, ‘Hey, do some sort of very, very simple, low cost study, and that gets you three extra years of exclusivity.’ And I have to imagine that that’s going to weigh on the court’s mind. It would just seem disproportionate to allow that sort of thing.”

UTC does not disclose how much it spent to conduct the BREEZE study. BREEZE was a Phase 1b study, using a small number of patients. It was short in duration with only a handful of study visits. It did not include any comparison group or placebo.

Phase 1 trials are the cheapest and research shows that the primary predictors of trial costs are the number of participants and number of patient visits.

Based on these factors, the cost of BREEZE may be in the ballpark of $10 million, though industry trial expenses may be inflated by corporate factors. Using a model from a 2021 HHS report and a generous estimate of $50,000 per patient, the clinical trial in the BREEZE study could be estimated to cost around $2.55 million for 51 patients. This estimated cost is for a Phase 1 trial of generic inhalers in 2020 dollars, the year UTC completed the trial, so no inflation adjustment is needed. This report also cited a 2019 issue of ONdrugDelivery magazine in which the CEO of Nanopharm wrote that the cost of a single, 900+ person clinical endpoint study of bioequivalence to bring a generic inhaler to market is around $45 million. Bioequivalence is typically assessed with bioavailability studies, and BREEZE was a bioavailability study — though at 51 participants, it was much smaller than this estimate and can therefore be assumed to have cost much less. An earlier report commissioned by HHS found that on average, Phase 1 trials for novel respiratory system therapeutics cost $5.2 million. Though this is generous — BREEZE did not study a novel therapeutic, but rather compared Tyvaso DPI to its predecessor Tyvaso — we also gave a generous estimate of inflation since the data used in that report’s model are from 2004-2012. Assuming the $5.2 million figure represents Jan. 2004 value (beginning of any data for the analysis), this high-end estimate puts the cost of the BREEZE study at $7.3 million in Dec. 2020 – when BREEZE was completed.

As Tu noted, $10 million is about equal to what UTC makes on Tyvaso products in just three days. That’s quite a bargain for three years of exclusivity.

“And drug prices actually go up over time, so the end portion of the drug’s lifespan is actually the most valuable portion,” Tu said. “So delaying a product’s launch is very significant.”

Of course, the court does not have to make an all-or-nothing decision.

If the scope of UTC’s exclusivity were narrowed to PAH patients — the population BREEZE studied — Liquidia could launch for PH-ILD patients only before May 2025. And this patient population is the most important market segment, due to the lack of treatment options for PH-ILD.

Expanding the Limited Options Available to PH-ILD Patients

Both pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease can be debilitating illnesses on their own — but the combination, PH-ILD, can lead to worse outcomes.

“It’s associated with increased risk of death, an increased risk of exacerbations, and worse symptoms. As such, PH-ILD is associated with increased challenges for the patients,” Dr. Nicholas Kolaitis told Hunterbrook. Kolaitis is a pulmonologist specializing in pulmonary hypertension and assistant professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Jordin Rice, a registered nurse at National Jewish Health who has focused on treating patients with pulmonary hypertension for the past six years, told Hunterbrook that PH-ILD is the worst type of pulmonary hypertension to have.

“These patients, unfortunately, they don’t have a long lifespan. We just don’t have a lot of treatments,” she said. “There’s a few things we don’t touch that we would use in other types of PH that don’t use in PH-ILD, and it makes it a difficult disease, because we really don’t have a ton of options, especially if somebody doesn’t tolerate a medication like Tyvaso.”

Rice said that the diseases are difficult to manage because patients progressively decline.

“Our goal as a clinic is to have people get on therapy that works well for them, and that means either maybe feeling the same, like maintaining what you have, or basically just not feeling worse on the medicine. You might feel better, you might feel the same, but you shouldn’t feel worse,” Rice said.

Rice noted, for instance, that inhaled treprostinil can improve exercise capacity in patients — helping them continue to engage in daily activities and supporting overall quality of life.

“We can’t overpromise that the medication is going to make them better, but the goal is to really maintain what you have and keep these pressures that are really high in your heart down, maybe more normalized,” Rice said.

Kolaitis told Hunterbrook that inhaled treprostinil also differs from medications that treat ILD alone (not PH and ILD) because it’s the only treatment that has been shown to actually help patients feel better.

Bringing Yutrepia to the market is important, experts told Hunterbrook, because it would expand the limited options available for PH-ILD, and competition from a new entrant could reduce the cost of these expensive medications.

“Certainly more options are beneficial to patients, right? Because the more options you have, the more affordability there will be, in general,” Kolaitis told Hunterbrook.

“The most realistic short-term strategies to address high prices include enforcing more stringent requirements for the award and extension of exclusivity rights increased competition contributes,” according to a 2016 JAMA article published by researchers from Harvard Medical School’s Program On Regulation, Therapeutics, and Law.

There are also limitations to the existing treatments, and each patient is unique — a product that works great for one person may be too difficult to use, intolerable, or ineffective for another. New formulations like the dry powder inhalers offered by Liquidia and UTC can also improve the usefulness of the treatments by making them more convenient and therefore easier to use regularly, and by delivering medication directly to the lungs — which could mean fewer side effects.

“Another medication would be helpful so we have another drug in our arsenal to treat people with,” Rice said.

For example, she noted that while nebulized the Tyvaso is the “gold standard” for PH-ILD patients, it needs to be taken four times per day, and because the device is the size of a “small cappuccino machine,” it’s not very portable — which can lead patients to miss doses.

“Tyvaso is really the only thing on the market right now for PH-ILD, so if there is something new that comes, we would probably really welcome it,” she said. “We can … lay out all these options, lay out the data we have, and patients can make a decision of what’s right for them and what fits their lifestyle. Because, to be honest, the nebulizer does not fit everybody’s lifestyle.”

Tolerability Issues, Lack of Data on UTC’s Tyvaso DPI Leaves Unmet Need for PH-ILD Patients

UTC’s Tyvaso DPI and nebulized Tyvaso are the only treatments currently available for PH-ILD. But neither Rice nor Kolaitis is comfortable prescribing Tyvaso DPI for these patients, leaving the nebulized version as their only option.

A recent guidance document The guidance document was created to aid health care providers — especially primary care physicians inexperienced in lung diseases — in diagnosing and managing pulmonary hypertension, with recommendations compiled by a roundtable of pulmonary hypertension experts. The American Lung Association and Pulmonary Hypertension Association convened the roundtable with funding support from the pharmaceutical company Merck. published by the American Lung Association and Pulmonary Hypertension Association also includes a footnote that Tyvaso DPI is “anecdotally associated with more cough” than nebulized Tyvaso.

Dr. Richard Channick — one of Liquidia’s expert witnesses in a patent litigation case — testified earlier this year that, in his experience, “patients who have used UTC’s Tyvaso DPI reverted back to the Tyvaso nebulized product due to Tyvaso DPI’s difficulty of use.” Channick is a pulmonologist at UCLA Health and a professor of medicine who specializes in treating pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease.

At National Jewish Health, Rice has seen similar challenges for PH-ILD patients who tried Tyvaso DPI.

“We started to notice quite a few issues pop up, like there were a few more side effects such as cough,” she said. “There were some people that did amazingly well for the first few months, they felt a lot more freedom using the smaller device. And then there were some that really failed it really quickly. They felt more hypoxemic, their oxygen dropped when they walked. It was a small group of people, but it was just something that raised some alarm bells for us to look at this really closely.”

Rice said she has seen much greater success with nebulized Tyvaso for PH-ILD than Tyvaso DPI — with only an 11% discontinuation rate (30% including discontinuation due to deaths) in their patient population. In contrast, more than half of the PH-ILD patients who tried Tyvaso DPI discontinued (50% of patients who switched from the nebulizer, 69% of patients who had never tried inhaled treprostinil).

This suggests the problem with Tyvaso DPI is more specific to the product, possibly related to the inhaler device UTC uses or the specific dry powder formulation, such as its inactive ingredients.

She noted that discontinuation rates for all pulmonary hypertension treatments are relatively high, due to tolerability issues with the active ingredients.

Rice has presented her clinic’s data on Tyvaso DPI for PH-ILD at conferences across the country — where others have told her about similar experiences with the product. The majority of Rice’s patients stopped taking the medication, mostly due to cough or a worsening of their condition.

“There’s certainly people that love Tyvaso DPI, and that it works well for. I’ve talked to those people, and we’re really happy that’s the case,” she said. “I just wish it was the case for more people, because it is really convenient. It does have a lot of good things about it, but our experience has kind of been remarkably different from what we expected.”

Rice and her colleagues are working on preparing their data for publication, she told Hunterbrook, highlighting the fact that there is still not a single published study on Tyvaso DPI use in PH-ILD patients — even over two years after its approval.

A Delaware District Court judge who reviewed evidence from UTC and Liquidia on the unmet “current market need” for PH-ILD treatments wrote in May: “Based on the present record, I am convinced that at least some patients would likely suffer negative consequences if Defendant were enjoined from launching Yutrepia for the PH-ILD indication.”

It’s hard to say how much of a game changer Yutrepia could be for patients without a full picture of its real-world use — which won’t come until it hits the market. Negative reactions to Tyvaso DPI have been reported since the product’s launch, though there is no conclusive link between the reported issues and the specific characteristics of UTC’s product.

Yutrepia Could Be a Better Option for PH-ILD

Liquidia claims Yutrepia could work better than Tyvaso DPI for PH-ILD patients, who have diminished lung capacity.

Yutrepia’s device is an inhaler that’s been used for treatment of “COPD and asthma for at least two decades,” said Liquidia Chief Medical Officer Dr. Rajeev Saggar. By contrast, Tyvaso DPI uses an adapted insulin inhaler not originally designed for individuals with compromised lung functions Liquidia’s Phase 3 trial of Yutrepia had a lower discontinuation rate – meaning fewer people dropped out of the study – than UTC’s Phase 3 trial of nebulized Tyvaso (24% vs. 41%). Both of these trials studied patients with PAH, not PH-ILD; Unfortunately, a head-to-head comparison between UTC and Liquidia’s products in PH-ILD is impossible as there’s no clinical trial data on Tyvaso DPI in PH-ILD. .

Rice explained that National Jewish Health performed an observational study on Tyvaso DPI to try and understand how the product would work for these patients whose “lungs are not 100%.”

“With a dry powder inhaler, you have to be able to create a breath strong enough to both break up the medication and disperse it into the lungs,” she said. “If a patient could not take a deep breath, or a quick enough breath, or basically produce enough force, would that impact the amount of medication they get? Would that impact the way they feel? Could it cause some declines in their condition?”

Kolaitis also has concerns about how compatible the devices are for patients with damaged lungs. “Dry powder inhalers can get really deep lung penetration when inhaled properly, with the right inspiratory force,” Kolaitis said. “But what we don’t know is that, in patients with ILD, how capable are they in getting that inspiratory force?” He added, “What we don’t know is whether the effect of the medicine is the same in patients with ILD when delivered via this dry powder inhaler. Essentially, does the dry powder act the same in patients with ILD as it does in those without?”

There’s variation among different dry powder inhalers, which can lead to variability in the product that works best for an individual patient.

“They have different resistance, you have to maybe have a really good posture while you’re taking it, some of them are very dependent on the way it’s tilted, if it’s taken at the wrong angle. So there’s some nuance, but there is good data that dry powder inhalers are helpful for various lung conditions,” Rice said.

“Is it possible that one of the devices could be better tolerated than the other one? It’s possible. Is it possible that for one patient, one device is tolerated better than the other device, and then for a different patient, it’s the opposite? That’s possible too,” Kolaitis told Hunterbrook.

But neither Rice or Kolaitis could speak to Liquidia’s claims that Yutrepia would work better for PH-ILD patients.

“Can I tell you one way or another? No. It might be that one of them is better than the other. Might be that they’re exactly the same. I don’t know because I can’t tell you that I’ve used both devices head-to-head in similar patients because one of them is not approved by the FDA,” Kolaitis said.

Data on how well PH-ILD patients tolerate Yutrepia will shape how providers feel about prescribing it. “We have concerns at our center, just about tolerability with the DPI, which I think we’d probably have with the Yutrepia inhaler as well, until we have more data on it,” Rice said. “There’s a few things that are different about it that, you know, I don’t know if that would make it more tolerable or not.”

Kolaitis is also concerned with the lack of clinical trial data on treprostinil dry powder inhalers for PH-ILD. He told Hunterbrook that he wouldn’t feel comfortable prescribing Yutrepia or Tyvaso DPI for these patients without evidence in the specific condition.

“Once there is data for a dry powder device in PH-ILD, that would probably be the one that I would favor, just because of ease of use and the existence of evidence. But until there’s actual clinical trial data on it, I personally will stick with the inhaled [nebulizer] device because, again, that is the one that was studied in this disease population,” Kolaitis said.

Still, Rice said the FDA’s exclusivity decision delaying Yutrepia was disappointing.

“As providers, we don’t care who makes the drug or where it comes from. We just want to make sure it’s helpful for our patients and that we have more options,” she said. “So it was kind of a sad thing for us, because if there were patients that didn’t tolerate Tyvaso DPI, we could have another option. They could very well not tolerate that one as well. But I think we look forward to having more options for people.”

And for now, Liquidia and UTC will be the only games in town. Both UTC and Liquidia face potential competition from Insmed’s treprostinil palmitil inhalation powder, or TPIP. TPIP’s appeal lies in its once-daily dosing, in comparison to Tyvaso DPI and Yutrepia — which are taken four times per day. Insmed is currently recruiting for a Phase 3 clinical trial of TPIP for PH-ILD, as well as Phase 2 and Phase 3 studies of TPIP for PAH. Liquidia is developing a twice-daily inhaled treprostinil product called L606, which would also reduce dosing frequency. L606 uses a “next generation” nebulizer that’s the size of an iPhone — much smaller and more portable than the Tyvaso nebulizer. The company is recruiting for a Phase 3 clinical trial that the FDA has confirmed will support both PAH and PH-ILD indications for L606. The L606 trial has an earlier anticipated study completion than TPIP’s trials, with Liquidia and Insmed racing to introduce less frequent dosing. Insmed did not respond to a request for comment

UTC Revives Claims Against FDA It Had Dismissed in August

In a September 16 filing, UTC brought its own claims against the FDA, asserting that the agency should have required Liquidia to file a separate application in order to add PH-ILD for Yutrepia.

UTC had already sued the the FDA over this issue — before dropping the suit just days after the agency granted the NCI exclusivity. The court was considering motions to dismiss that suit altogether before UTC voluntarily withdrew it. The FDA and Liquidia each filed motions to dismiss UTC’s claims, citing multiple other instances where the FDA has allowed products to add additional indications via amendment. The FDA sent a letter to UTC on Aug. 16 — the same day it awarded the retroactive NCI exclusivity and issued Yutrepia tentative approval for PAH and PH-ILD — justifying the addition of the PH-ILD Indication via amendment. In it, the FDA identified six products where it has allowed the same course of action, establishing precedent for accepting Yutrepia’s amendment: Pemetrexed (NDA 208297); Fulvestrant (NDA 210326); Romidepsin (NDA 208574); Paclitaxel (NDA 211875); Bortezomib (NDA 209191); Paclitaxel (NDA 216338).

Multiple legal experts Hunterbrook spoke to questioned whether UTC’s earlier lawsuit over Yutrepia’s application spurred the FDA to grant this exclusivity.

“It feels to me that they sort of made a decision, and then because of this litigation and the intense scrutiny, other people came and took another look, a closer look, and decided, where do we want to be on something like this?” Garvin observed.

“The delay in granting the exclusivity, the ‘flip flop’ on the exclusivity summary, in light of the other litigation, suggests that FDA may be acting in a very considered manner here, thinking about what’s the outcome that they can defend most easily,” the anonymous lawyer specializing in FDA matters said. “And unfortunately in this case, for patients, that means one product on the market instead of two.”

The agency may also have considered this exclusivity as a path of least resistance, given its approaching expiration in May. “If there were three years left, maybe FDA comes out differently,” the anonymous lawyer said.

Tyvaso DPI Exclusivity Award Could Be Vacated or Sent Back to FDA, Potentially Allowing Yutrepia to Launch Before May 2025

Experts told Hunterbrook that it’s hard to predict the outcome of this lawsuit because it’s such an unprecedented situation.

“I don’t know of anything that mirrors this. This is very odd,” Garvin said.

If Liquidia does prevail, it’s unlikely the court would order the FDA to grant immediate approval of Yutrepia.

“Maybe, there’s certain nuts-and-bolts aspects of an application that are no longer approvable, So even if you were to disagree with us,” Garvin said the FDA would argue, “you got to give it back to us so we can double-check everything before this thing gets on the market.”

Regardless of the outcome of the litigation, this abnormal waffling on exclusivity reflects poorly on the FDA, according to legal experts.

“This went down in a way that FDA I don’t think wants things to go down. They don’t want to be second-guessing their own position on exclusivity after the approval of a product,” Garvin explained.

The anonymous lawyer specializing in FDA matters called the move “embarrassing” for the FDA and pointed to the initial summary as evidence that “at least part of the agency” did not think Tyvaso DPI deserved exclusivity. “That’s the part of the agency that’s more well-versed in clinical information than the sort of legal side,” the anonymous lawyer said. “It doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence in FDA, from someone who watches these exclusivity determinations carefully.”

While the FDA made a reasonable argument to defend its decision, “it seems like a very small study to extend the fourth product from UTC to block a competitor that’s been waiting in line, fighting off all the patents and things like that,” the lawyer added. “I mean, the day they got tentative approval was the day that they announced the three year exclusivity for UTC. It’s just not how an agency should operate.”

Judge Kelly Sided with Plaintiffs in Past FDA Challenges

This isn’t the first time Kelly will be deciding a dispute over FDA exclusivity. Eagle Pharmaceuticals Inc. sued the agency for denying orphan drug exclusivity to its cancer treatment, Bendeka. Kelly sided with Eagle in 2018, finding the FDA’s interpretation contrary to the plain text of the law and ordering it to grant the exclusivity. The FDA challenged the ruling, but lost its appeal in 2020.

In another recent lawsuit challenging an FDA flip-flop, Kelly stayed final approval of a generic epinephrine injection from BPI Labs LLC and gave the agency six weeks to reevaluate its decision.

Kelly’s history suggests that he will look closely at the statutory text and Congress’s intent behind the law. It’s also notable that while Kelly ruled against the FDA in these cases, his decisions were in favor of the exclusivities. There’s also a call-back to Kelly’s early legal career: He helped defend the maker of notorious recalled diet pills — which can causepulmonary hypertension, among other heart and lung problems — in patient injury lawsuits. The cases Kelly worked on were resolved with a massive Diet Drug settlement, but there have since been reportedly over 50,000 lawsuits filed and over $21 billion paid out to patients who suffered lung and heart damage after taking the diet pills.

Competition From Yutrepia Could Bring Cost Savings

Another potential benefit of bringing Yutrepia to market is that competition typically drives down prices. A lack of competition invariably results in patients paying more for their drugs. “Promoting Competition To Address Pharmaceutical Prices,” Health Affairs Policy Options Paper, March 15, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20180116.967310; Rajkumar, S.V., (2020). The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions. Blood Cancer Journal, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020- 0338-x; “In Focus: Selected Issues in Pharmaceutical Drug Pricing,” Congressional Research Service Report, March 1, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12337 Exclusivity gives drugmakers monopoly power, allowing them to set prices without market forces as a check.

According to Kolaitis, potential cost savings could be one of the primary benefits of getting another option on the market.

“These medicines are not cheap, and I don’t know what the cost is going to be if the Yutrepia device is approved, but typically, when there’s two different competing companies that are making the same device or same medicine, typically that reduces the cost, because typically the other company will have a pricing scheme that makes them competitive,” he said. “So I think from a cost standpoint, could it be beneficial? Yes.”

He noted that patient assistance programs are common for treatments like these, and differences in the terms between each company’s program could apply to different patients, potentially helping expand access.

At a Wells Fargo Investor Conference on September 5, Kaseta said, “Pricing strategy is a critical component to our launch strategy,” but declined to offer further details on how much Liquidia will rely on price to compete with UTC.

UTC itself has acknowledged it would face pressure on pricing if Liquidia’s drug came to market.

In another patent case against Liquidia, one of UTC’s expert witnesses testified that Yutrepia could launch at a 20%-30% discount from Tyvaso DPI, “placing pressure” on UTC “to offer price concessions as well.”

Tyvaso DPI is an expensive drug. A recent investor presentation from Insmed Inc. (NASDAQ: $INSM), which is developing a competitor treprostinil inhaler with once-daily dosing called TPIP, noted the “list price” of Tyvaso DPI was around $300,000 in March 2024.

According to the telemedicine company and price tracker GoodRx, a maintenance kit of 112 packages (a roughly 28-day supply, given Tyvaso DPI’s four-times-daily dosing) of 64 mcg Tyvaso DPI has an out-of-pocket cost of $26,456. Drugs.com puts the estimated cash-price, before insurance, of the same dose and supply at $24,233.84.

In 2022 (the most recent data available), the average cost per claim — meaning an individual payment the programs made when a beneficiary got Tyvaso DPI — was $21,277.43 for Medicaid and $22,843.38 for Medicare Part D. Recent spending is likely much higher, as the price of Tyvaso DPI has increased since it launched in mid-2022.

Duan explained that while a single new entrant doesn’t typically lead to dramatic price drops, meaningful price differences are still often seen, “because of the fact that you have a duopoly instead of a monopoly.”

“The fact that you have these two products in competition means that there will be choices and choices tend to drive prices down,” Duan said.

Individual patients may not see most of the savings from Yutrepia as few patients could likely afford paying cash for such expensive specialty drugs, relying on health insurance coverage and manufacturer assistance programs to foot most of the bill. That means the greatest benefactors of reduced costs may actually be insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, and the government (and therefore, taxpayers who would benefit from lower prices through reduced costs to Medicare and Medicaid).

Once Yutrepia Launches, UTC Will Turn to Reimbursement Strategies to Defend its Market Share — But Insider Sales Indicate Company May Not Be Sure How Effective This Will Be

In anticipation of competition from Liquidia, UTC has already updated its contracts with payers (aka insurance plans and other middlemen like PBMs).

During UTC’s most recent earnings call, President and Chief Operating Officer Michael Benkowitz said the company had negotiated “terms very favorable to UTC Therapeutics” that include rebates and assurances that plans will not give preference to competitors.

It’s another tactic straight out of the Big Pharma playbook: Drugmakers offer insurers and PBMs rebates in exchange for plan designs that keep patients from switching to a competitor.

Formularies are lists of drugs that insurance plans cover. Plans design formularies to shape the treatments patients get, setting restrictions like prior authorizations and separating drugs into “tiers” that correspond to patient out-of-pocket cost. Patients are incentivized to use drugs in lower tiers because they have lower copays.

It’s a quid pro quo: Drugmakers pay rebates to health plans for giving their product favorable placement on the formulary.

“We think entering into these contracts now positions us very favorably for when a competitor comes to the market because we will, at that point, have rebate dollars already flowing through the payers, and we have parity and non-disadvantaged language,” Benkowitz said. “I think they’re going to be reluctant to just turn those off overnight. And so we thought it was important to kind of get those contracts in place.”

Which is to say, don’t worry folks: Even if Yutrepia is approved, UTC will probably be able to keep its aircraft hangar — at least for a little while.

Though, Benkowitz may not be as confident in the company’s prospects as he sounds in that interview — based on his sales of UTC stock. In the last month alone, he has dumped nearly $29 million worth of shares according to FactSet — with this year marking his highest ever pace of selling.

Martine Rothblatt, the company’s CEO, has also been selling UTC stock more prolifically than ever — bringing her sales in 2024 to over $191 million.

AUTHOR

Laura Wadsten is a journalist based in Washington, D.C. She is also Executive Director of the nonprofit Moving to Value Alliance, where she produces and occasionally co-hosts the MTVA Unscripted Podcast. Previously, Laura wrote about antitrust and health care markets as a Correspondent for The Capitol Forum, a premium subscription financial publication.She was a Hodson Scholar at Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a B.A. in Medicine, Science & the Humanities.

EDITOR

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.