Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time.

The Hastings High class of 2000 suspects that something is deeply wrong.

Its Facebook group is usually a place where former classmates reminisce. About the last victory of the high school football team in the old stadium back in 1999. Or about that school storage closet dubbed “the green room” because of the Mountain Dew bottles students taped to the wall.

But lately, the Facebook group has become a chronicle of tragedy.

One classmate recently died from leukemia. Another succumbed to chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, a debilitating autoimmune disorder. A third classmate’s daughter died from brain cancer.

One post asks group members if they have daughters with health issues. The responses include a litany of birth defects, neurological disorders, and other diseases. Children with anencephaly, biliary atresia, arteriovenous malformation.

For a small town and a class not even middle-aged, it doesn’t seem right.

“I don’t see just our daughters having issues,” one classmate wrote. “It’s our children in general. It’s also some of our classmates. I see many of our classmates with infertility, miscarriages, migraines, arthritis, chronic pain, unknown autoimmune issues, cancers, just seems to be a lot of health issues within our classmates and some of the surrounding other classes.”

This Facebook thread and an anomaly in Hunterbrook Media’s nationwide database of toxic emissions led us to investigate what’s going on in Hastings, a town best known as the birthplace of Kool-Aid.

Our investigation found a long history of environmental pollution.

The classmates were just toddlers when their hometown made national headlines in 1986 as Nebraska’s first Superfund site — a federal designation reserved for the most contaminated locations, where pollution is so severe it requires long-term cleanup under a special program.

The class of 2000 grew up on at least partially remediated ground, but people in Hastings are still getting sick at extraordinarily high rates, according to National Cancer Institute data.

Adams County, which includes Hastings, had the highest leukemia rates in Nebraska between 2017 and 2021, with an age-adjusted incidence rate of more than 19 cases per 100,000 people. The County’s bladder, brain, and thyroid cancer rates are also among the highest in the state for those years.

Hunterbrook’s investigation revealed a possible explanation for the continued spate of illness.

One of the companies the EPA originally deemed responsible for the contamination isn’t only still operating in Hastings, it’s also still emitting the same chemical that poisoned the community in the first place.

A second factory next door appears to be emitting toxic chemicals as well, according to Hunterbrook’s analysis of EPA data.

The situation mirrors many communities across the United States that are on the long path toward remediation after decades of industrial pollution, but suddenly face the risk of new contamination due to lax oversight.

So we visited Hastings — where there is a distinct odor in the air, and a sense that something is wrong, but nobody seems to know exactly what has happened. Our job was to try and find out.

Rare Diseases, Unknown Causes

On the Sunday afternoon of Memorial Day weekend, Amy Hamburger stood on her front porch with Conner, her 14-year-old son.

Hamburger had posted about his medical problems in the Facebook group. “I have a son with lots of medical problems. He is 14 and they still can’t figure out what has caused the many different medical diagnoses he has,” she wrote.

“He’s put us through a lot,” she told a visiting Hunterbrook reporter.

“He has intellectual disability. … He still has a feeding tube. Low muscle tone. Microcephaly, his head’s super small.”

“What do you mean?” asked Conner, speaking through a new microphone she’d given him.

“Your head’s super small,” replied his mother.

“I know, like a bowling ball,” Conner remarked.

Osteopenia. Weak bones. A major back surgery, right around Christmas.

How did he feel now?

“Good,” Conner boomed into his microphone.

“He always feels good,” explained Amy. “He has such a high, high pain tolerance, too. He broke his arms, two years ago at school, and went half the day with two broken arms. Didn’t say a word. Then they must have really started bothering him. The nurse calls me. And I’m like: ‘What, Conner’s complaining about pain?’ So I picked him up, and he’d broke both his arms!”

“Yeah, but I’m still here,” remarked Conner.

“Well, yeah, you’ll be here for a long time buddy.”

“Yay!” he exclaimed into the microphone.

Hamburger said she was raised in Hastings, which means next to the Superfund sites and the remnants of decades-long pollution. Right after graduating, in 2001, she and Conner’s father left Hastings for Lincoln. But 15 years ago, she moved back to her hometown, where she still had family.

“I needed help with you,” she told Conner.

She recounted the numerous maladies of her classmates and their children. She described the classmate’s daughter with a rare liver issue, and the one who died from a brain tumor.

The cause? Unknown.

She said her father, who worked in construction, had told her “about some of the EPA stuff way out on Highway 6, and some of the old factories. … He just says there’s junk out there. They need to clean that up. Why the government hasn’t done it is beyond him.”

Conner chimed in: “Meh, I just have fun.”

“You do just have fun. You live your life.”

“Yeah, totally,” her son replied.

“Mhm.” Hamburger laughed. “You don’t know. You’re just a happy go kid. Whatever he’s been through has not stopped him one bit, which is a plus.”

She reflected on the mystery of his ailment and the history in Hastings that may have caused it.

“It’s just bizarre.”

“Yup,” nodded Conner. Then he looked up from under the porch at the darkening sky.

“Might be some more rain coming,” he said.

Something in the Air

The answer to why Hamburger’s son is sick — and why so many of her classmates or their children have fallen ill — may be just blocks away, according to Hunterbrook’s investigation.

Less than two miles from her home, two inconspicuous brick factories sit in the center of Hastings, Nebraska, along U.S. Highway 6, which stretches from California to Massachusetts, dividing the town into north and south.

The smaller factory is owned by the Dutton-Lainson Company, a storied Nebraskan manufacturer founded in 1886.

The larger plant belongs to the Flowserve Corporation ($FLS), a multinational conglomerate.

What many residents said they didn’t know: According to EPA data from 2020, these nondescript industrial facilities harbor an invisible menace: The neighborhood that abuts the factories has one of the highest cancer risk levels in the entire country.

The EPA estimated Dutton-Lainson — a winch manufacturer — was among the 15 top emitters of trichloroethylene (TCE) in 2020. Dutton did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

TCE is a toxic industrial chemical. It causes liver cancer, kidney cancer, and blood cancer, as well as damage to the nervous and immune systems, including elevating the risk of Parkinson’s.

TCE is the culprit in A Civil Action, a movie starring John Travolta, based on the nonfictional account of actual litigation seeking restitution for people with cancer — a series of cases that ultimately generated over $75 million in payments.

The EPA in December issued a ban that would have phased out TCE for most industrial uses by the end of 2025, but the rule is in limbo after industry groups and Republicans in Congress challenged it. The Trump administration is reviewing the ban and could decide to roll it back.

Next door, Flowserve — a multinational manufacturer of industrial pumps and valves — was among the top 40 emitters of hexavalent chromium (Chromium VI) in 2020, according to data it submitted to regulators in April of 2021. In January 2025, the company resubmitted its 2020 emissions report and now says its emissions were actually 10 times lower due to an error in its original filing.

Hexavalent chromium is another toxic industrial chemical, often used in electroplating, stainless steel production, leather tanning, textile manufacturing, and wood preservation, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. It’s linked to lung cancer, nasal cancer, and sinus cancer, among other conditions.

It’s also the toxin in Erin Brockovich, starring Julia Roberts, a dramatized account of the actual, intrepid paralegal who catalyzed a $333 million settlement for victims of groundwater contamination in California.

Rather than being located in an industrial park, the Dutton-Lainson and Flowserve factories sit across from family homes and local businesses.

The residential block across from Flowserve’s facility between Kerr Avenue and N. Briggs Avenue has the 11th-highest lifetime cancer risk in the entire country, according to the EPA’s estimates from 2020: a chance of 8 in 10,000.

According to the EPA’s definition, a risk of 8 in 10,000 means that eight people out of 10,000 “assumed to be exposed under similar conditions could develop cancer as a result of lifetime exposure to one or more potential carcinogens.” If the EPA updates its numbers based on Flowserve’s revised emissions estimate, the assumed cancer rate calculation may be much lower.

That’s eight times higher than the threshold the EPA deems acceptable, rivaling the cancer risk of Louisiana’s infamous Cancer Alley.

A Toxic Legacy

The government established the Superfund program in 1980 to clean up hazardous waste sites.

Public awareness of the health risks caused by chemical contamination had grown in the 1970s after toxic dumps such as Love Canal in Niagara Falls and the so-called “Valley of the Drums” in Kentucky received national attention. The Superfund program also requires the responsible parties to either remediate the sites themselves or reimburse the government for cleanup work led by the EPA.

The agency calls the Hastings Superfund site one of its “largest and most complex groundwater cleanup projects,” with seven subsites. The contamination stretches about five miles from the city center to the east and southeast.

Hastings inadvertently discovered the shocking level of toxins in the water when it reactivated an old well in 1983; within hours, a local resident complained about her drinking water’s strange odor and taste.

Three years later, the EPA placed Hastings on its National Priorities List. An investigation found that a vapor degreasing operation, former landfills, a coal gas plant, an industrial park, and a grain elevator had contaminated public and private water supplies.

The EPA identified a smorgasbord of toxic chemicals: “benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene (BTEX) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in subsite soils and groundwater.”

The government closed four municipal wells in 1983 because of TCE, according to a City of Hastings statement sent to Hunterbrook. It took years to identify the potentially responsible parties mandated by the EPA to remediate the sites.

Among those parties: Dutton-Lainson.

A 2006 decision of the Nebraska Supreme Court, stemming from a lawsuit the company filed against its liability insurers for declining to cover cleanup costs, laid out how its chemicals had contaminated the soil and groundwater in Hastings. Ultimately, Dutton was only awarded a fraction of the $5 million in damages it sought.

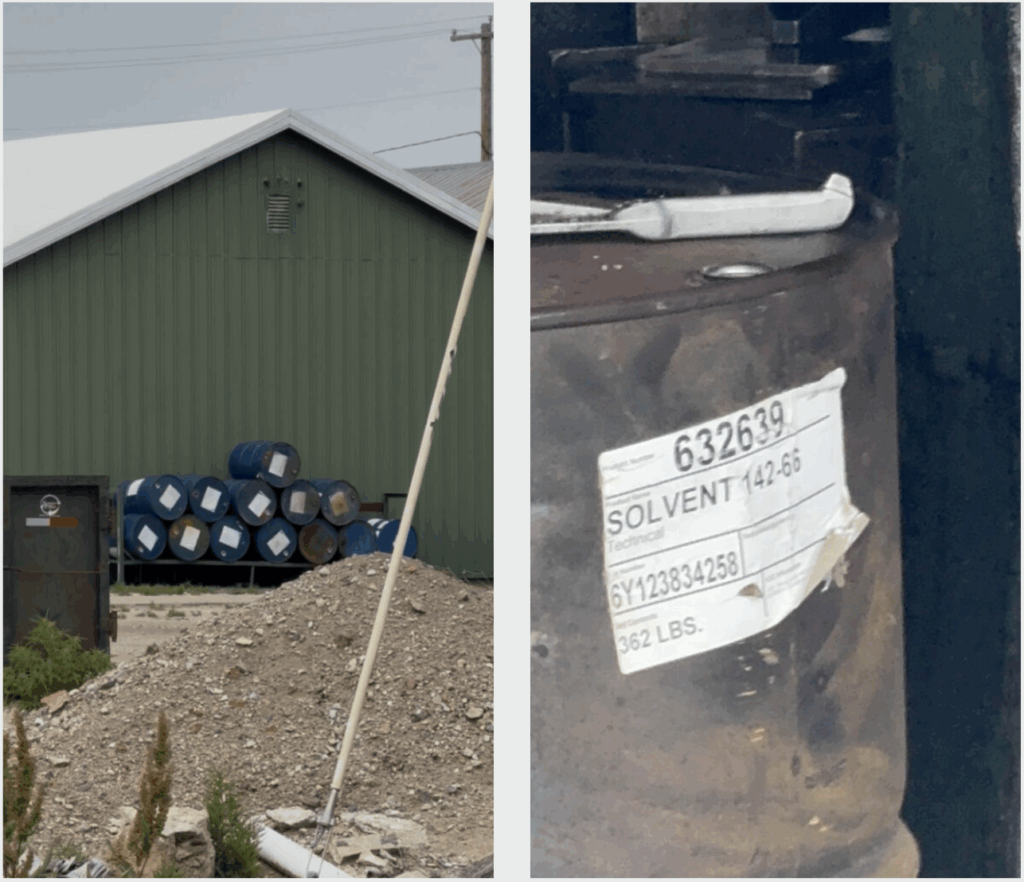

According to the Supreme Court opinion, from the 1960s to the 1980s, Dutton deposited metal drums containing TCE and 1,1,1, trichloroethane (TCA), also a solvent, in the North and South Landfills, both operated by the City of Hastings. The drums were then either emptied out into the landfills or crushed with bulldozers.

“This was done either directly by Dutton employees or by the landfill operators with full knowledge of Dutton,” the Court concluded, while noting that this was done “in compliance with then-existing laws and ordinances.”

The opinion recounts that, from 1948 to 1987, solvents containing TCE and TCA also spilled onto the concrete floor of its plant in Hastings and seeped into the groundwater underneath the building and an adjacent property — the area, still home to Dutton-Lainson’s factory, is now known as the “Well No. 3 subsite.”

Cleanup activities at the Well No. 3 subsite started in 1996, with the company treating contaminated soil and groundwater. Dutton-Lainson also began operating a groundwater extraction system in May 2003 and still samples the water twice a year. The EPA has conducted several five-year reviews of the Dutton-Lainson subsite.

After Decades of Cleanup, Toxic Emissions Continue

People in Hastings talk about the contamination in their city as if it is ancient history. But EPA data, public records, and interviews show that the pollution never stopped.

Over the past 30 years, Dutton-Lainson has emitted an average of about 30,000 pounds of TCE annually, according to emissions numbers the company submitted to the EPA Toxic Release Inventory (TRI).

| Dutton-Lainson’s TCE emissions over the past 30 years | |||

| Year | On-Site Fugitive Air (lbs) | On-Site Stack Air (lbs) | On-Site Total Air Emissions (lbs) |

| 1995 | 250 | 64,000.00 | 64,250.00 |

| 1996 | 250 | 54,000.00 | 54,250.00 |

| 1997 | 250 | 51,000.00 | 51,250.00 |

| 1998 | 250 | 43,000.00 | 43,250.00 |

| 1999 | 250 | 30,700.00 | 30,950.00 |

| 2000 | 250 | 28,575.00 | 28,825.00 |

| 2001 | 250 | 22,983.00 | 23,233.00 |

| 2002 | 250 | 30,838.00 | 31,088.00 |

| 2003 | 250 | 31,795.00 | 32,045.00 |

| 2004 | 5 | 29,506.00 | 29,511.00 |

| 2005 | 5 | 29,217.00 | 29,222.00 |

| 2006 | 5 | 35,290.00 | 35,295.00 |

| 2007 | 5 | 30,329.00 | 30,334.00 |

| 2008 | 5 | 26,275.00 | 26,280.00 |

| 2009 | 5 | 18,005.00 | 18,010.00 |

| 2010 | 5 | 23,311.00 | 23,316.00 |

| 2011 | 5 | 22,421.00 | 22,426.00 |

| 2012 | 5 | 20,047.00 | 20,052.00 |

| 2013 | 5 | 21,255.00 | 21,260.00 |

| 2014 | 5 | 23,946.00 | 23,951.00 |

| 2015 | 5 | 22,597.00 | 22,602.00 |

| 2016 | 5 | 26,810.00 | 26,815.00 |

| 2017 | 5 | 28,066.00 | 28,071.00 |

| 2018 | 5 | 25,221.70 | 25,226.70 |

| 2019 | 5 | 30,068.12 | 30,073.12 |

| 2020 | 5 | 26,815.00 | 26,820.00 |

| 2021 | 5 | 28,560.00 | 28,565.00 |

| 2022 | 5 | 20,473.64 | 20,478.64 |

| 2023 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2024 | 5 | 13,895 | 13,900 |

Dutton-Lainson did not report its TCE emissions to the EPA Toxic Release Inventory in 2023. It did, however, submit emissions reports to Nebraska’s Department of Environment and Energy, now the Nebraska Department of Water, Energy, and Environment (DWEE), which show the company emitted 7,220 pounds of TCE that year.

The cleanup efforts at Dutton-Lainson’s Superfund subsite are focused on removing TCE from groundwater. But EPA reports show that the continuing air emissions pose a similar risk to human health as the groundwater pollution.

In a multiyear analysis, the agency modeled the exposure of people living close to facilities that use TCE for degreasing, including Dutton-Lainson’s. It found that in 51 out of 53 cases, the cancer risk for fenceline communities exceeded EPA benchmarks at a distance of 100 meters, or about 330 feet. This is also true for Dutton’s plant, the report shows.

Dave, an electrician who told Hunterbrook he’s worked at the Dutton-Lainson facility for 40 years, confirmed that the company is still using TCE today. “We use TCE for degreasing,” he said, standing next to his truck in the Dutton-Lainson parking lot.

He said the TCE situation is better than it used to be and hasn’t caused him problems personally. He described how Dutton-Lainson cleaned up a pool of TCE three years ago. Now, the factory tracks the number of TCE barrels it’s using.

“They’re getting touchy about it recently. The government is getting touchy about it. That’s the scuttlebutt.”

“They’re getting touchy about it recently. The government is getting touchy about it. That’s the scuttlebutt.”

Public records show that in 2015 Dutton reported a TCE spill at its Hastings facility to the Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality — now also part of Nebraska’s DWEE. The letter states that a normally open valve of a degreaser had been closed to take a sample and then not reopened, which ultimately caused 40 gallons of TCE to overflow and spill “out onto a cement floor where it evaporated.” The company claims the substance did not enter the ground or stormwater system.

But factory floor spills like this one caused the contamination below its facility, as the Nebraska Supreme Court noted.

The DWEE and the EPA told Hunterbrook they aren’t aware of any other chemical releases at the facility.

Flowserve Can’t Get Its Numbers Straight

Less than 500 feet from Dutton-Lainson’s facility, just a little farther down Highway 6, sits the second-largest emitter of hexavalent chromium in Nebraska, according to EPA AirToxScreen tool data from 2020. Flowserve emitted about 190 pounds of the carcinogenic substance that year, the agency estimates based on the company’s total reported chromium emissions. Chromium releases can include either hexavalent chromium, which is toxic and carcinogenic, or trivalent chromium, which is nontoxic and generally considered harmless. A standard formula in the 2020 National Emissions Inventory Technical Support Document estimates that 34% of reported total chromium emissions are of the hexavalent form.

The numbers the EPA calculated for Flowserve, based on the data the company submitted in 2021, put the company in the top 40 of hexavalent chromium emitters in the country, and raised the cancer risk in adjacent census blocks to some of the highest levels in the country, according to the agency’s modeling. But the EPA apparently never confirmed with the company whether its estimate was actually accurate.

“When possible, EPA Region 7 partners with state agencies and facilities to verify emissions estimates. Due to the limited screening nature of AirToxScreen, we have not directly verified the accuracy of the 2020 [National Emissions Inventory] reported emissions estimates of hexavalent chromium for this facility,” the EPA’s Midwest office said in a statement to Hunterbrook.

In January 2025, Flowserve resubmitted its emissions report for 2020 and now says its chromium emissions that year were actually just a fraction of what it originally reported. According to a company spokesperson, the high emissions numbers it submitted to the DWEE were the result of a data entry error.

In response to questions from Hunterbrook, Flowserve attributed the error to changes in the way regulators requested data to be submitted. The DWEE, however, stated that it did not make any such changes during the relevant time period.

Hunterbrook asked the DWEE if regulators had reviewed Flowserve’s new numbers and if the company had presented any evidence that its emissions were actually significantly lower, but the department did not respond.

For 2024 the company originally reported 480 pounds total of chromium emissions, which would mean it still emitted about 163 pounds of hexavalent chromium, according to the EPA’s standard formula.

But the company now says it made yet another data entry error and is working with regulators to change its emissions report for that year as well. The DWEE confirmed that it had given the company access to review and amend the record. Flowserve says it expects the revised chromium numbers to be significantly lower, similar to the emissions reduction for 2020.

Hastings residents will have to take the company’s word for it.

Proposed TCE Ban Stuck in Limbo

New EPA regulations on air emissions could help lower the cancer risk in Hastings.

In December 2024, the agency issued a rule that would effectively ban TCE by the end of 2025 for most industrial uses — including degreasing at Dutton-Lainson. Only a limited number of critical industries would be allowed to phase out the substance over a longer period, with more robust worker protections in place.

The new rule was originally intended to take effect in January, but both industry and environmental groups disagree with the TCE exposure limits included in the ban (albeit for different reasons), and are challenging it in court. House Republicans have proposed a joint resolution that would prevent the agency from enforcing the rule.

While litigation is ongoing, the TCE ban is on hold and its future is uncertain.

The EPA has said that the rule is subject to an executive order signed by President Trump on January 20, which freezes all pending regulations for review, meaning that the administration could simply decide to roll back the ban.

In other words, it doesn’t appear regulators will be coming to Hastings’ rescue anytime soon.

That’s bad news for the residents of the neighborhood next to the factories — the handful of bucolic tree-lined streets between Kerr Avenue and North Briggs Avenue that boasts the 11th-highest cancer risk in the entire country. So Hunterbrook asked residents for their stories.

“I just lost my wife to cancer,” said Bob, who was working on a couple of cars in his friend Bill’s driveway over Memorial Day weekend. Dutton-Lainson loomed at the end of the street.

“I just lost my wife to cancer,”

He said that her name was Corinne. Breast cancer. They’d lived together two doors down.

TCE is a known cause of breast cancer.

“Well, I’m probably lucky,” said Bill, a former automotive body man who has driven for Dutton-Lainson. “I’ve been here 30 years but I’m only home on the weekends because I drive trucks for a living. But my wife, she’s had a lot of health issues lately.”

Bill demonstrated how metal dust from the factory floats through the air and wreaks havoc on the paint jobs of his cars. “We spent a whole day cleaning this car, and it’s already getting back on it.” He explained, “It’s metal out of the foundry.”

He sprayed the hood of the first car with Iron Removing Spray Clay, which turns from white to purple in the presence of metal particulates. On the hood of the small white sedan he’d been cleaning that day, it took a minute for the spray to become purple. Then, on the hood of his truck, the foam immediately turned dark purple.

“Well, you know, that foundry’s sitting right there,” said Bob, referring to the Dutton-Lainson facility at the end of the street. “I mean, shit, we’re not that far from it.”

“And this isn’t the first time it’s happened,” added Bill. “Supposedly, they just redid the foundry because people were complaining about it.” He said the factory paid to clean an earlier car of his, after the metal in the air “messed it up pretty good too.”

They both said Dutton-Lainson treats its people well, including a worker who got injured. And they explained the history of the EPA facility across town, finishing each other’s sentences.

“It all boils down to the NAD —” said Bill, referring to the Naval Ammunition Depot, where Hastings hosted the largest inland World War II naval ammunition plant, now another EPA Superfund site.

They’re “just burning the dirty ground,” he said.

“Just burning the dirty ground,”

“It was all contaminated,” added Bob. “That was back when the Navy —”

“— Where they built bombs and stuff —”

“— I know there’s a lot of contamination out there —”

“They used to just have bottled water because you weren’t supposed to drink the water —”

“— You couldn’t even drink the water.”

“— You couldn’t even drink the water.”

Another couple of blocks over, Cindy Moore lost her husband, David Moore, to cancer in 2018.

“David died,” she began. She didn’t think it was the factories. Lung cancer ran in his family.

“David’s family, out of eight people, seven of them had the same kind of cancer. They all died. … Mom. Dad. ’Bout two brothers and ’bout two sisters. David was the one that lived the longest so far.”

“David’s family, out of eight people, seven of them had the same kind of cancer. They all died.”

She added, “I’ve got cancer now.”

“It’s between my lungs. I had a kidney removed ‘cause of cancer. That was white cell.”

White blood cell cancers include leukemia and lymphoma — both linked to chemicals polluting Hastings.

“I did five weeks radiation, and two treatments of chemo. That put me in the hospital for 12 days. So now I’m doing infusions,” she said.

Over by the middle school — just off Highway 6 — Dick Urwin’s wife, Merna Urwin, died of cancer in 2019. She was 65.

“She went to Vegas with her girlfriends. When she came back she had a stomach ache. It was pancreatic cancer. That’s the end of it. We don’t need no interview.”

Maddie, the bartender at Steeple Brewing Company — equidistant between Dutton-Lainson/Flowserve and the EPA Superfund site — described multiple cancer clusters.

“Four or five of our elementary school teachers have had cancer,” she recalled. “We had signs up that said, ‘Do not drink the water if you’re pregnant,’ and we remember that, like, oh, that’s weird. It’s okay for us eight-year-olds to drink it?”

“Four or five of our elementary school teachers have had cancer,” she recalled. “We had signs up that said, ‘Do not drink the water if you’re pregnant,’ and we remember that, like, oh, that’s weird. It’s okay for us eight-year-olds to drink it?”

She also said, “There’s certain areas where a ton of neighbors have cancer. Up by Marian Road and Lochland Road, there’s three or four people who have had cancer.”

“I don’t know if it’s something to do with the pollution in the water.”

The City of Hastings told Hunterbrook that no TCE has been detected in its drinking water since the well contamination was first discovered in 1983.

Whether the government will enact or repeal the TCE ban remains uncertain. And residents in Hastings continue to wonder why so many of them have gotten sick.

For now, emissions from the two downtown factories continue. Across the street, a billboard advertises jobs at Flowserve. The other side of the billboard is an ad for a cancer center.

AuthorS

Till Daldrup joined Hunterbrook from The Wall Street Journal, where he focused on open-source investigations and content verification. In 2023, he was part of a team of reporters who won a Gerald Loeb Award for an investigation that revealed how Russia is stealing grain from occupied parts of Ukraine. He has an M.A. in Journalism from New York University and a B.S. in Social Sciences from University of Cologne. He’s also an alum of the Cologne School of Journalism (Kölner Journalistenschule). Till is based in New York.

Nathaniel Horwitz is CEO of Hunterbrook. He has contributed to The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, The Harvard Crimson, The New York Times, and The Australian Financial Review. He co-founded, invested in, and served on the boards of several biotechnology companies, ranging from AI-designed medicines for cancer to cell therapies for autoimmune diseases. He has a BA in Molecular Biology from Harvard, where he coauthored biomedical research in the scientific journal Cell. His first job out of high school was reporting for his hometown newspaper. He volunteers as executive chair of the 501(c)(3) education nonprofit Mayday Health.

EditorS

Sam Koppelman is a New York Times best-selling author who has written books with former United States Attorney General Eric Holder and former United States Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal. Sam has published in the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, Time Magazine, and other outlets — and occasionally volunteers on a fire speech for a good cause. He has a BA in Government from Harvard, where he was named a John Harvard Scholar and wrote op-eds like “Shut Down Harvard Football,” which he tells us were great for his social life. Sam is based in New York.

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2026 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.