Three mysterious entities. Tens of billions in revenue.

Our multinational investigation reveals how CVS, UnitedHealth, and Cigna created new subsidiaries to divert billions of dollars from health plans and patients.

All three tried to keep it secret. None answered repeated questions. CVS sued to stop evidence getting out. Cigna called the police on a reporter.

And the cost isn’t just higher drug prices. People have died.

Hunterbrook Media’s investment affiliate, Hunterbrook Capital, does not have any positions related to this article at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. Hunterbrook Media and its affiliate Hunterbrook Law are working with a litigation firm that may bring potential legal claims based in part on our reporting. See full disclosures below.

If you have information related to PBMs, PBM GPOs, or other topics investigated in this article, please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share with Hunterbrook Media, which can keep you anonymous.

Vacant again.

Reception: empty. Offices: deserted. This time, mail piled by the door.

Multiple visits found no activity at the ghost headquarters in Minnesota. There was a logo on the wall: a company with no apparent website, contact email, or phone number.

An entity whose address only appeared in lawsuits.

Zinc Health Services.

Across the ocean in Ireland, the same phenomenon.

A security guard escorted a Hunterbrook Media reporter through a building in Dublin to the offices of a company supposedly headquartered within. We’re referring to this location as Emisar’s HQ because job postings at Emisar list two Optum office locations, both in Ireland: Dublin and Letterkenny. The Letterkenny office appears to be a smaller, satellite location and Optum’s Ireland operation lists the Dublin address as its registered office. We visited the office in Dublin, which The New York Times referred to as Emisar’s office. In court filings, the company has rejected claims that it is based in Ireland, citing its Delaware incorporation, but we could not find evidence of an Emisar physical presence or office in the United States.

Emisar Pharma Services.

Again, no website, email, or number.

A dozen or so cubicles. Fluorescent lights illuminating empty chairs.

No one there.

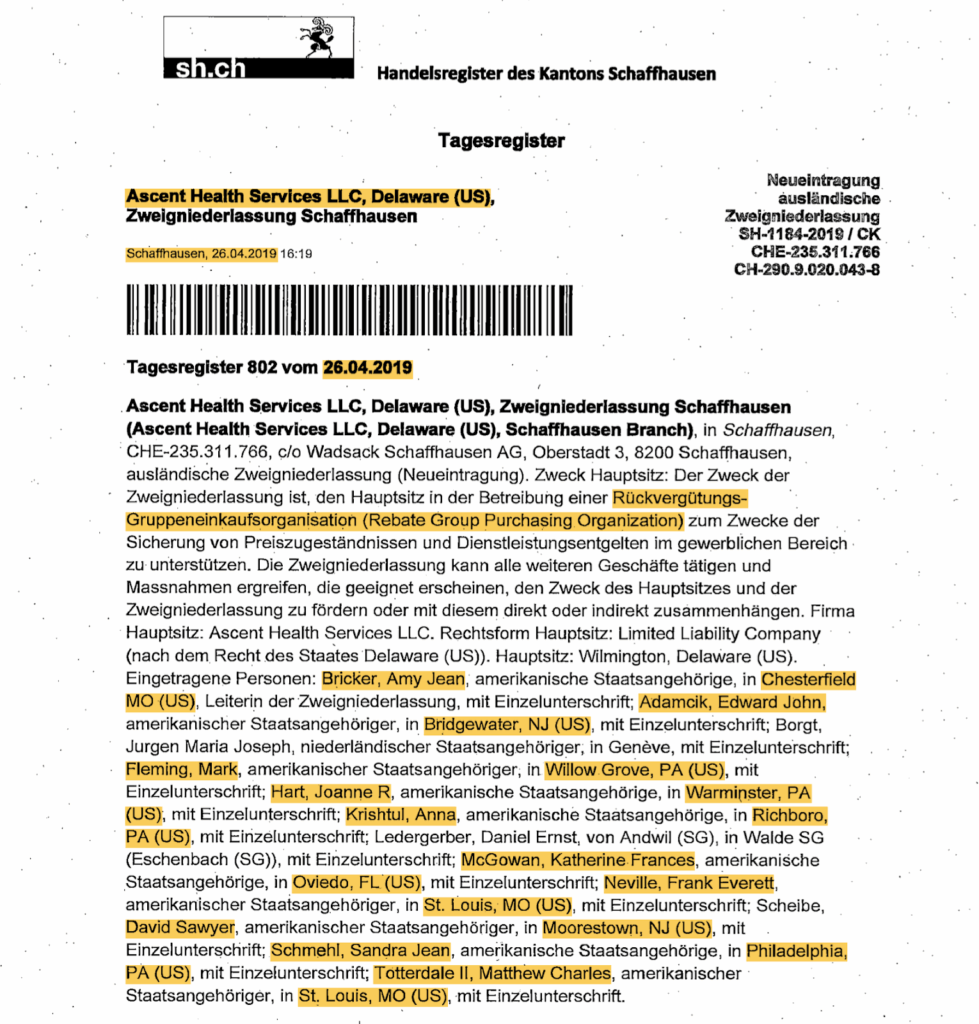

A third company occupied a one-floor headquarters in the scenic Swiss town of Schaffhausen, known as a haven for luxury watches and tax avoidance by American companies.

Ascent Health Services.

This one has a website.

There were a half-dozen employees in the office, and dozens of others apparently work remotely.

But after Ascent called the Swiss police on a Hunterbrook reporter observing from a neighboring kebab shack, two executives refused to answer questions or even share contact information for the company — despite a request from the Polizei.

Three supposed headquarters. Three countries. Three entities that seem to barely exist, relative to their purported revenue.

According to financial records, lawsuits, and dozens of interviews, these three entities — Zinc, Emisar, and Ascent — may be among the most lucrative companies in the world, bringing in tens of billions of dollars for their parent conglomerates.

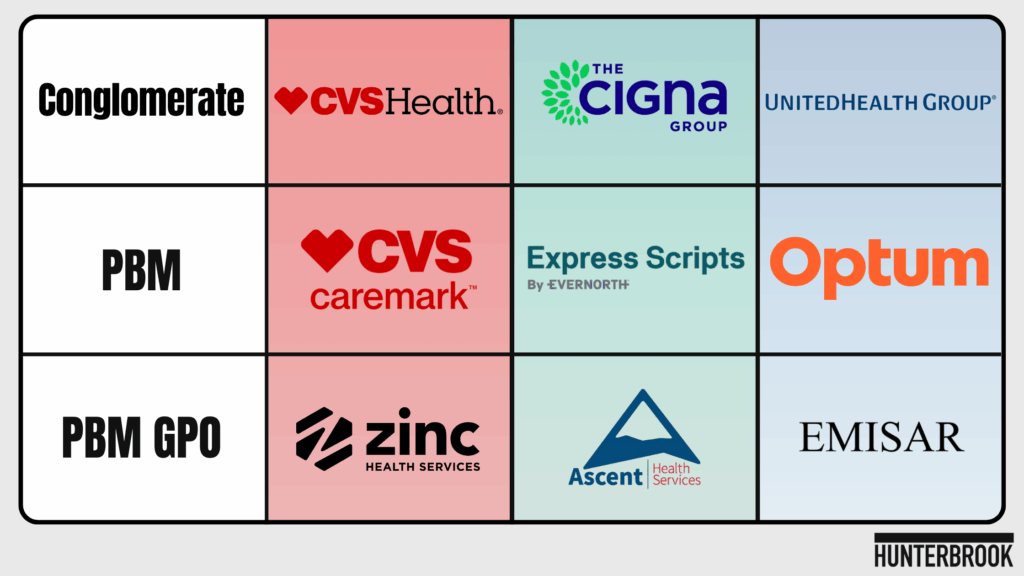

If you’re reading this investigation from the United States, there’s about a nine-in-ten chance that one of these corporations plays a role in what you pay for healthcare. The Big Three Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) — CVS Caremark, UnitedHealth’s Optum Rx, and Cigna’s Express Scripts — managed 80% of total prescription claims in 2024. The fourth- and sixth-largest PBMs — Humana Pharmacy Solutions and Prime Therapeutics, with 2024 market shares of 7% and 3%, respectively — also use Ascent to aggregate rebate negotiations. 80% + 3% + 7% = 90% market share. Additional smaller PBMs also use the Big Three PBM GPOs, experts told Hunterbrook.

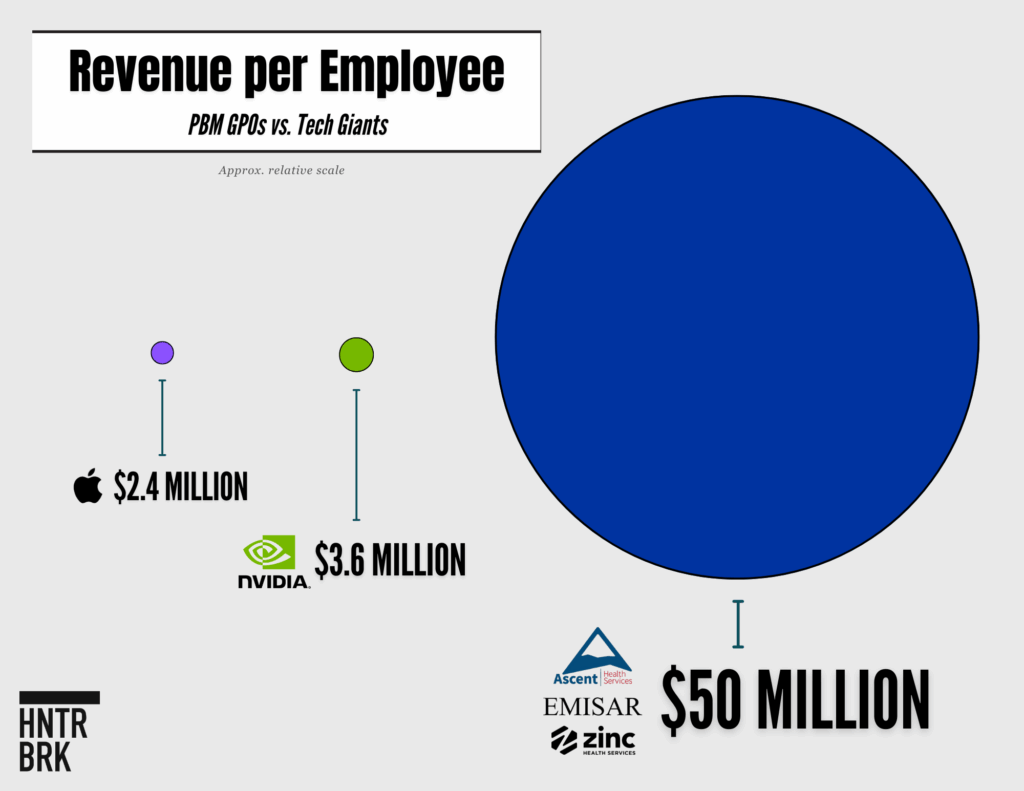

So what are these companies? And how do they appear to generate 25 times the revenue per employee as companies like Apple or Nvidia?

The Middlemen of Medication Coverage

Who decides what drugs your insurance covers — and how much you’ll pay for them?

It’s not your doctor or employer. It’s not even your insurer.

It’s a middleman: a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM).

Over 80% of America’s prescription drug market is reportedly controlled by the “Big Three” PBMs: Optum Rx, CVS Caremark, and Evernorth Express Scripts. Their parent companies UnitedHealth Group ($UNH), CVS Health ($CVS), and Cigna Group ($CI) are some of the largest corporations in the world, ranking third, fifth, and 13th, respectively, on the Fortune 100 list in 2025.

These three companies grip every corner of healthcare, from the drugmaker to the doctors who write prescriptions to the pharmacies that dispense drugs.

PBMs originally emerged in the 1960s to process insurance claims for prescriptions. Since then, they’ve evolved into complex intermediaries with enormous market power.

The premise is straightforward.

By combining the buying power of health insurance plans, PBMs are meant to secure better deals for those plans from drugmakers. These discounts often take the form of “rebates” — payments from drugmakers to PBMs, typically a percentage of the product’s list price. Rebates are supposed to reduce the cost of medication for health plans and their members.

Really, it often looks more like a quid pro quo: Drugmakers pay rebates for favorable placement on the list of drugs covered by a given health plan, called a “formulary.”

PBMs design those formularies, determining which drugs make it on the list and how they’re covered. Because PBMs historically keep a cut of the rebates they negotiate for each health plan as compensation, drugmakers offer bigger rebates in exchange for PBMs giving their products the best spot on a formulary.

Over time, PBMs began to keep a greater and greater slice of rebates for themselves. A Nephron Research report estimates total commercial rebate value in 2022 at $64 billion; a BRG whitepaper funded by PhRMA provides 2023 estimates of total commercial “Negotiated health plan and PBM rebates and fees” at $143.3 billion, and rebates to the “Medicaid Drug Rebate Program” at $51.6 billion. A Pew study from 2019 estimates PBM pass-through from 2012-2016 at around 91% to commercial payers, and estimates total rebates in 2016 at $89.5 billion. The Drug Channels Institute 2024 Report estimates that “the gross-to-net bubble, which measures total rebates and discounts paid by manufacturers, reached $334 billion for all brand-name drugs in 2023.” A 2018 Health Affairs article noted, “We estimate a total of $89 billion in rebates on brand name drugs were passed through to health plans and insurers, with the largest amounts collected by Medicaid ($32 billion) and Medicare Part D ($31 billion), and a smaller amount collected by private insurers ($23 billion). These figures exclude rebates that were retained by PBMs and not reported in our data sources.” During a May 2023 Senate HELP committee hearing, executives from CVS Health, Express Scripts, and Optum Rx testified that they passed through over 95% of rebates to clients.

Eventually, scrutiny metastasized.

Red and blue states alike began to regulate PBMs.

State attorneys general, President Trump’s first administration, and Lina Khan’s Federal Trade Commission each shined a light on PBMs.

Efforts to crack down on the middlemen gained broad bipartisan support.

Clients started wising up to the scheme, demanding that 100% of rebates negotiated by PBMs be passed through to the health plans the PBM was acting on behalf of. Employers insisted that they should receive the discounts on drugs paid for by their health plans for their employees, not PBMs.

The days of rebate profiteering seemed numbered — at first.

The Middlemen’s Middlemen: Big Three Create Secretive “PBM GPOs”

With their cash cow at risk, the Big Three PBMs pivoted.

To keep more of the money while technically fulfilling promises to pass through all rebates, PBMs created secretive new subsidiaries.

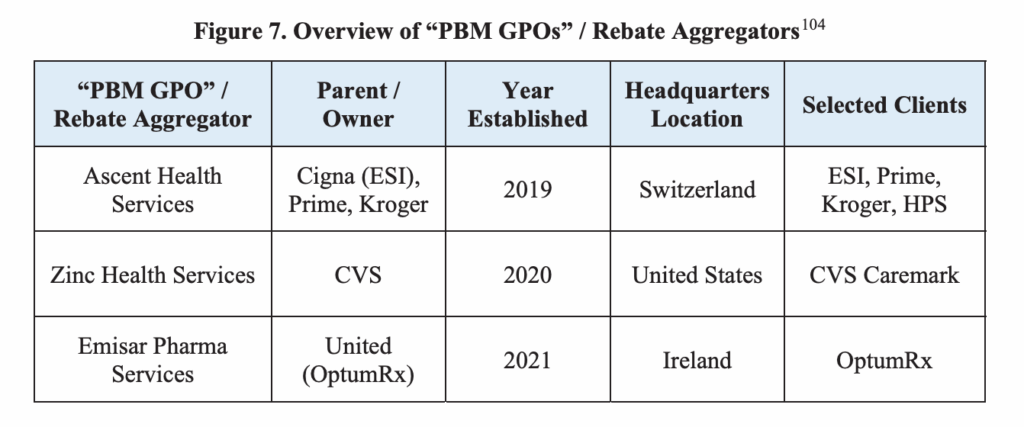

The PBMs branded these new backroom entities PBM “Group Purchasing Organizations” (PBM GPOs). Certain payments to group purchasing organizations (GPOs) are exempt from the federal Anti-Kickback Statute. The safe harbor provision at 42 C.F.R. 1001.952(j) allows a GPO to keep payments from vendors so long as the GPO arrangement meets certain transparency requirements and payments are not conditioned on referrals to a federally funded healthcare program, like Medicare. According to FAQs on the HHS OIG website, PBM payments from drugmakers could arguably fall under the GPO safe harbor, if the specific arrangement complies with all aspects of the provision. William Sarraille, a professor of practice at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, published an analysis of the FAQ and safe harbor situation on Substack in November 2024. See subheading PBM “GPOs” Aren’t Even GPOs for more on how Zinc, Ascent, and Emisar differ from traditional GPOs.

The FTC, by contrast, calls them “rebate aggregators.”

These entities in Minnesota (Zinc), Dublin (Emisar), and Schaffhausen (Ascent) are little known and have faced limited scrutiny.

Hunterbrook interviewed executives and former staffers from each entity and their parent PBMs; spoke with health plans, drugmakers, and other industry experts; analyzed insurance, healthcare, and employee data; visited offices from Ireland to Switzerland; applied to job posts; and reviewed thousands of pages of contracts and court records.

The takeaway: PBM GPOs appear to generate astronomical revenue with skeleton staff — making Zinc, Emisar, and Ascent among the world’s most lucrative enterprises on paper, even though they appear barely to exist in the real world.

“They are covers for the Big Three to say in a contract that they pass through 100% of the rebates they get.”

— Mark Cuban, co-founder of Cost Plus Drugs

“A lot of the functionality of PBMs has shifted away from the nucleus into its surrounding rings. If you look at a GPO level, the truth is that we’re looking at around 95% of all claims transactions that are running through three companies,” said Antonio Ciaccia, co-founder and CEO of the prescription drug data analytics nonprofit 46brooklyn Research and president at 3 Axis Advisors, a healthcare consulting firm.

A few health plans have caught on to the scheme through reviews of their own financials. These health plans have recovered tens of millions of dollars from PBMs and their GPOs, according to public audit reports and court filings.

Health insurance benefits are often a company’s second-largest expense behind payroll. Employer healthcare costs are projected to increase 10% in 2026, according to data from the nonprofit employer group the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans. Rising awareness of the PBM problem has some employers looking beyond Caremark, Optum, and Express Scripts. In the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions’ annual survey, 61% of employers reported contracting with one of the Big Three PBMs in 2025, down from 72% the year prior. In the same poll, 55% of employers said they were considering switching PBMs, and an additional 6% had changed vendors in the past year. The largest private employer in Maryland, Johns Hopkins University, ditched Express Scripts for Capital Rx in 2024. Fortune 100 company Tyson Foods also left the Big Three — dropping Caremark for Rightway — and reported saving 13.5% on annual pharmacy costs.

But thanks to the GPOs, switching PBMs doesn’t necessarily free companies from the grip of the healthcare oligopoly: Other PBMs go through Zinc, Ascent, or Emisar to negotiate with drugmakers, industry insiders told Hunterbrook.

These Big Three have extracted and retained billions in rebates and other fees from drugmakers, while purportedly acting on behalf of thousands of health plans operating in the U.S.

“You get 100% back of what you know about, but not the stuff they’re hiding.”

— MIchael Sherman, former chief medical officer of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care

Industry insiders confirmed Hunterbrook’s findings about PBM GPOs.

“They are covers for the Big Three to say in a contract that they pass through 100% of the rebates they get,” the billionaire Mark Cuban, co-founder of Cost Plus Drugs, told Hunterbrook.

Dr. Steve Miller had helped create Ascent while chief clinical officer at Cigna and Express Scripts, where he successfully challenged Pfizer and other drugmakers to lower the price of medicines ranging from statins to the antiparasitic whose price was jacked up by Martin Shkreli. Miller explained that PBM GPOs “double-, triple-dip on fees.” He said that at first, health plans and their consultants didn’t know about it.

Kent Rogers, who helped create Emisar while senior vice president at UnitedHealth’s Optum, confirmed that the PBM GPOs bring in “tens of millions, if not close to $100 million, per employee.”

PBMs claim that PBM GPOs receive these payments from drugmakers for services they provide, like data processing and rebate negotiation.

But according to Hunterbrook’s visits to these companies’ ostensible headquarters, as well as its review of employment websites and interviews with numerous industry experts including former employees, few people work at Zinc or Emisar. While Ascent boasts a larger team, it is still one of the most lucrative companies in the world, relative to its actual size.

The Big Three and their affiliates were functionally unresponsive to this investigation. Hunterbrook sent repeated inquiries to CVS Health/CVS Caremark (the owner of Zinc); Cigna Group and Evernorth Express Scripts (the owner of Ascent, which was also repeatedly contacted directly); and UnitedHealth Group and Optum Rx (the owner of Emisar) seeking clarity on the PBM GPOs. None answered Hunterbrook’s questions and a couple even took steps to interfere with the investigation.

Multiple industry stakeholders said the situation felt like smoke and mirrors.

“We reached out to PBMs and we said, ‘Hey, can you explain to us what these GPOs do?’ They said the GPOs are going to negotiate with the drug companies to get the very best deals, because they are going to aggregate all of the covered lives that we have, for all of our customers. And we said, ‘That doesn’t make any sense, because that’s exactly what a PBM is supposed to do! So what exactly is the GPO going to do?’ They gave us a Cheshire Cat grin, and no more information,” James Gelfand told Hunterbrook.

Gelfand is president of the ERISA Industry Committee (ERIC), a lobbyist group that represents large, self-funded employers on health and benefit plans issues.

“The way the scam is intended to work, the PBM farms out what used to be the PBM’s job to the GPO … The entire thing was a scam in order to be able to do that fee function that we just described as a way of hiding that money so it is never disclosed to the plan sponsor,” he added.

According to a former Zinc executive, the work PBM GPOs allegedly do for pharmaceutical companies is largely a mirage.

“It was all on paper and it was all transactional money flowing through contracts. There was nothing I had to send to you or to sell to you,” they said, asking to remain anonymous due to what they described as a pattern of “retaliation” from the Big Three.

“The Stuff They’re Hiding”

UnitedHealth Group’s then-CEO Sir Andrew Witty had promises to keep.

“This morning we are committing to a full 100% pass-through of all rebates we negotiate at the PBM back to the payer, the state, or the union,” he proclaimed on his January 2025 earnings call. On the same earnings call, Witty told investors that, “Last year, our PBM passed through more than 98% of the rebate discounts we negotiated with drug companies to our clients,” but UnitedHealth Group reportedly does not publish data that would be necessary to verify the claim. Witty also said the company intends to make sure that “100% of rebates will go to customers by 2028 at the latest.”

It was the first earnings presentation since the killing of Brian Thompson, CEO of the insurance division that provided three-quarters of the conglomerate’s more than $400 billion in 2024 revenue.

Witty’s pledge responded to a question from a JPMorgan analyst: How would UnitedHealth navigate efforts to outlaw the lucrative rebates drugmakers paid PBMs? JPMorgan is currently facing a class action lawsuit alleging the company mismanaged its own employees’ pharmacy benefits, in breach of its fiduciary duty under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). According to the complaint, JPMorgan not only overpaid for drugs but also let its own venture, Haven Healthcare, fail in order to appease industry players like CVS Caremark — which is both a client of JPMorgan and the PBM contracted to provide its employees prescription drug coverage. The case against JPMorgan was part of a string of lawsuits seeking to hold employers accountable for allowing PBMs to waste plan funds and overcharge patients. One major hurdle these plaintiffs have faced is proving they have “standing” — that employees suffered concrete, direct harm due to the employers’ mismanagement of PBMs. As of the time of publication, JPMorgan’s motion to dismiss appears to be fully briefed and is pending before the court.

But it wasn’t a particularly hard promise to make.

Because by then, Optum and its peer PBMs had spent years moving money around: Optum was receiving payments from the pharmaceutical industry through its PBM GPO, Emisar.

“The pharma companies aren’t paying less, they’re paying differently,” hypothesized Michael Sherman, former chief medical officer of the nonprofit Harvard Pilgrim Health Care system.

“By categorizing as fees not rebates, and laundering through the GPOs, they don’t have to pass through the rebates, they’re somehow carving it out.”

Miller corroborated Sherman’s speculation. Drugmakers “were reducing rebates to pay Ascent more,” he told Hunterbrook.

Rogers echoed Sherman and Miller in testimony to the FTC. “The industry feared that the rule would make the rebate system illegal,” he said, referring to the first Trump administration’s “rebate rule,” which removed rebates from a regulatory safe harbor that had protected drugmakers and PBMs from prosecution under the Anti-Kickback Statute. Pharmaceutical rebates were long considered exempt from the federal Anti-Kickback Statute under a safe harbor provision. In July 2020, Trump issued an executive order directing the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to finalize proposed regulation removing rebates from the “discount” safe harbor. HHS published the final rule in November 2020, but a PBM industry trade group sued and got the rule struck down. Still, according to FAQs on the HHS OIG website, PBM rebates in Medicare Part D are illegal — unless the entire rebate amount is shared with the patient at the pharmacy counter (aka the “point of sale”). But this is just the agency’s stated interpretation of the regulation, not a settled matter of law. The OIG FAQ also notes two other safe harbors PBMs could arguably fall under: the “GPO” safe harbor, or the “personal services” safe harbor.

“The intention of the G.P.O. is to create a fee structure that can be retained and not passed on to a client,” Rogers told The New York Times in 2024. (Years after the emergence of PBM GPOs, this article from the NYT appears to be the first time the PBM GPOs received substantive media scrutiny.)

Cigna recently made the same promise as UnitedHealth Group. In its latest earnings call, an executive all but admitted the commitment to rebate pass-through was performative.

“You should think of this as not meaningfully changing from today in terms of client level earnings contributions, meaning that we would expect comparable earnings contributions from our rebate-free model as we have today in our existing solutions,” said Brian Evanko, president and chief operating officer of Cigna Group.

In an interview with Hunterbrook, Rogers said PBM GPOs were a necessary solution to replace the lost revenue stream from rebates.

He blamed hospital markups and other parts of the pharmacy supply chain for the affordability crisis in U.S. healthcare.

The former president of Express Scripts and co-founder of Ascent, Amy Bricker, also argued that PBMs and PBM GPOs help reduce prices. It’s hard to conclusively say whether PBMs are “worth it,” or if eliminating PBMs would achieve greater savings. A 2023 Visante analysis funded by PBM lobbying group PCMA claimed, “PBMs save payers and patients 40-50% on their annual drug and related medical costs compared to what they would have spent without PBMs.” But an April 2025 analysis found that Ohio saved $140 million in two years by kicking PBMs out of their state Medicaid program.

“I’ve testified a number of times in front of Congress and had pharma at the table,” Bricker told Hunterbrook. Bricker left Express Scripts to become chief product officer at CVS Health, but Cigna successfully sued to prevent Bricker’s transition to CVS based on her noncompete. “In every one of those hearings, drugmakers are asked, if we did away with rebates, would you lower your list price unilaterally to make up for those rebates? Not once was the answer yes.” When testifying before Congress, representatives of the pharmaceutical industry have been cautious about promising price cuts and generally decline to unequivocally state that they would reduce list prices if rebates were eliminated. However, Hunterbrook identified one instance where a clear commitment was offered: During a 2019 Senate Finance Committee Hearing, AstraZeneca CEO Pascal Soriot said, “if the rebates were removed from the commercial sector as well, we would definitely reduce our list prices.”

Rogers agreed, telling Hunterbrook: “You may not like it, but it’s not illegal.”

The legality appears to be an open question based on recent litigation.

In 2024, the Illinois Attorney General recovered $45 million from CVS Caremark for retaining money from Zinc that should have been passed through to the state health plan that Caremark and Zinc represented.

CVS capitulated in a settlement prior to any litigation. In addition to the money, the settlement explicitly modified the contract between Caremark and the state to ensure that rebates negotiated by Zinc, as well as Caremark itself, would be fully passed through to the state.

“The Illinois case tells you: Forget the cost of litigating. Even aside from that, they don’t want to talk about this publicly: Let’s make this go away,” said Sherman.

The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA) CVS Health, Express Scripts, Optum Rx, and Prime Therapeutics are members of PCMA. — a lobbying group for the PBM industry — provided the following statement to Hunterbrook regarding PBM GPOs:

“GPOs are used in health care and many other industries to aggregate purchasing volume and obtain lower prescription drug costs for patients. Employers and PBMs should be able to use every tool at their disposal to push back against the high drug prices set by drug companies. PBMs, including smaller market companies, need the leverage provided by GPOs to aggressively negotiate with drug companies to secure savings on lifesaving medications for patients and employers.”

CVS Sued To Stop Release of Public Records Revealing That PBM GPOs Don’t Pass Through Revenue to Health Plans and Patients

After Hunterbrook requested further information about the case from Illinois under the state’s Freedom of Information Act, Zinc’s owner, CVS, sued to stop the state attorney general from releasing the information without significant redactions.

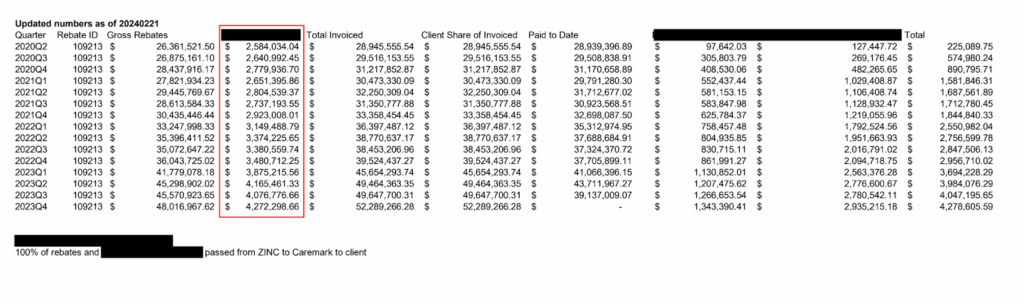

The information Hunterbrook did receive, however, showed a gap between what drugmakers paid Zinc and what Zinc ultimately passed through to CVS and therefore patients.

The same exhibit stated, “100% of rebates and [Redacted] passed from ZINC to Caremark to client.”

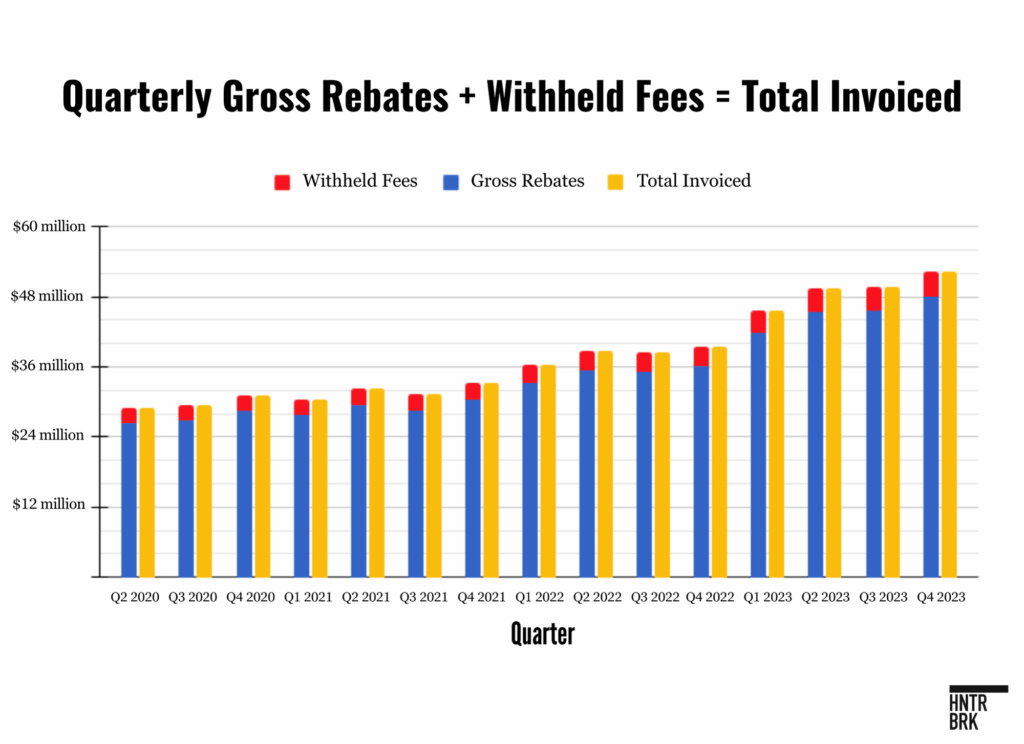

The share of funds not passed through (the left-most redacted column in the table above, outlined in red (“Column 4”) — appeared to grow substantially from 2020 to 2023.

During that period, Column 4 payments totalled nearly $49 million — a similar amount to what Zinc was later forced to pay in settlement — accounting for 8.66% of the total invoiced each quarter, on average. And this was just one health plan among thousands across the country.

On the chart above, the numbers in Column 4 show the amount left when “Gross Rebates” are subtracted from the “Total Invoiced.” Therefore, this difference likely represents fees — such as “Manufacturer Administrative Fees” — Zinc itself charged drugmakers for its services on behalf of a plan.

The amounts in Column 4 fluctuate in lockstep with rebates — whenever “Gross Rebates” increase over the previous quarter, the value in Column 4 increases by roughly the same proportion. This suggests the amounts in Column 4 are, like rebates, calculated as a percentage of drug list prices.

The attorney general’s office declined to comment for this story, citing active litigation.

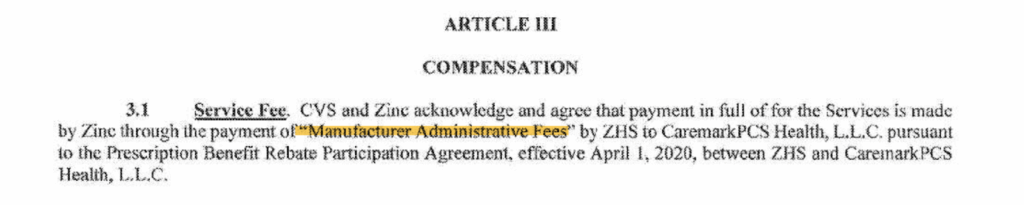

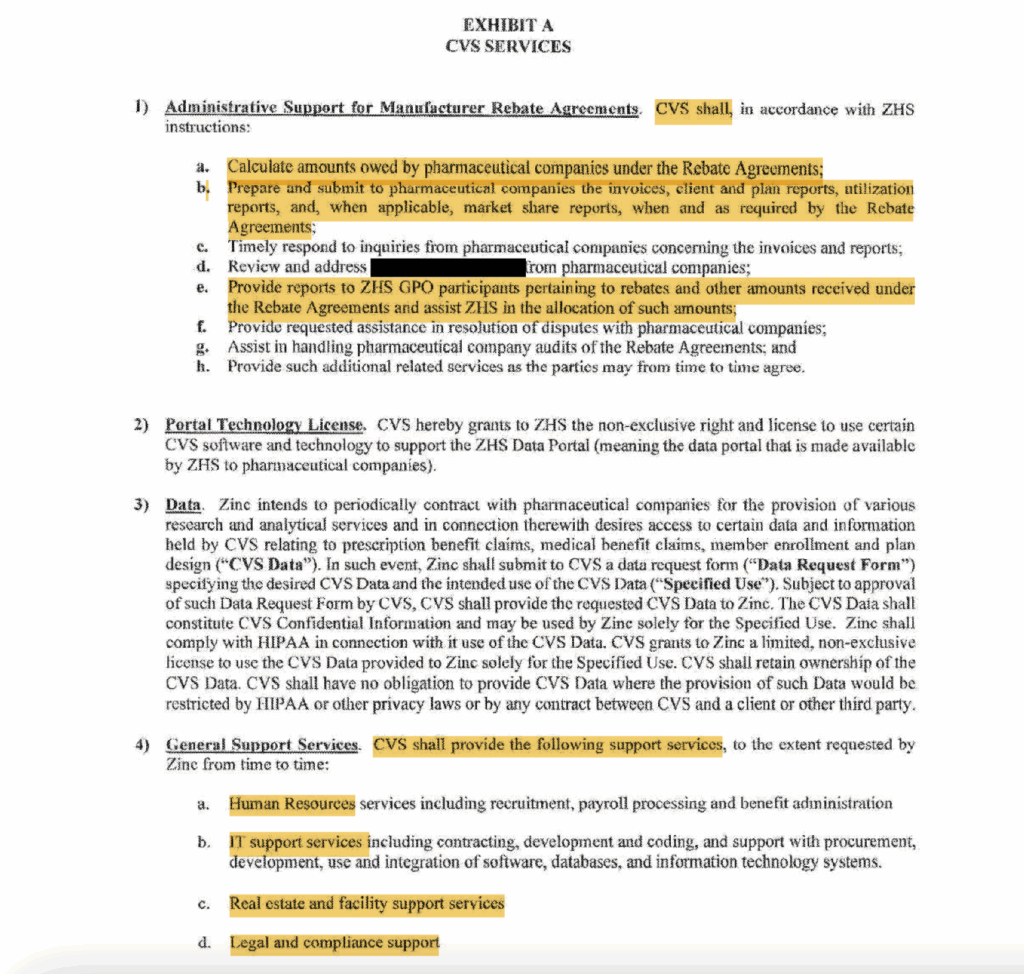

The documents from the Illinois case also include Zinc’s contracts with CVS Caremark (the PBM) and CVS Pharmacy.

The contract between Caremark (“Company”) and Zinc (“GPO”) states:

“Company and GPO acknowledge and agree that a portion of the [Redacted] remitted by GPO to Company constitutes compensation for services rendered by Company to GPO pursuant to that certain Services Agreement, effective April,1 2020, between Zinc Health Ventures, LLC, the parent company of GPO, and CVS Pharmacy, Inc., the parent company of Company.” “This Prescription Benefit Rebate Participation Agreement, effective as of April 1,2020 (‘Effective Date’), is entered into by and among Zinc Health Services, LLC, a Delaware limited liability company (‘GPO’), and CaremarkPCS Health, L.L.C., a Delaware limited liability company (‘Company’).” Emphasis added.

The redacted term appears to be “Manufacturer Administrative Fees” — based on the “Services Agreement” between Zinc and CVS Pharmacy.

It’s tricky teasing out the exact division of work between Zinc and its parent company.

The “Services Agreement” suggests that CVS outsourcing to Zinc is mostly a formality: In fact, Zinc hires CVS Caremark to do work that the PBM says falls under the GPO’s responsibilities. Zinc then pays a portion of the manufacturer administrative fees to Caremark in exchange for these services.

The services Zinc pays Caremark for include “General Support Services” — like Human Resources, IT Support, and Legal and Compliance Support — as well as “Administrative Support for Manufacturer Rebate Agreements.”

In the latter category, CVS seems to handle the accounting, reporting, and drugmaker correspondence for rebate payments between Zinc and drugmakers.

What work is left for Zinc?

According to the contract, Zinc “is engaged solely to provide the rebate contracting and financial analysis and consultation services described herein.”

The analysis and consultation services appear to involve modeling how different terms in plan contracts would impact the amount of money paid by plans. Aside from the parts of “rebate contracting” assigned to CVS, it seems as if Zinc is solely securing rebate deals with pharmaceutical manufacturers.

The agreement also shows that CVS Caremark sees how money flows between the drugmakers, GPO, PBM, and plan clients — even if CVS won’t let its plan clients see this information. Experts told Hunterbrook that PBMs often make it difficult for plan sponsors to audit rebates and discounts, telling clients they don’t have access to, or are prohibited from disclosing, rebate and fee data.

Greg Baker, the CEO of AffirmedRx — an independent PBM that positions itself as a more transparent alternative to the Big Three — called claims that Zinc, Ascent, and Emisar lower drug prices “a blatant joke.”

“It’s profiteering that hurts patients in the long run,” Baker told Hunterbrook.

“Where there’s mystery there’s margin,” U.S. Rep. Jake Auchincloss, a Democrat from Massachusetts, told Congress.

Visits Indicate PBM GPOs Are Largely Shells

Emisar — owned by Optum and UnitedHealth

In response to an FTC lawsuit last year, Optum Rx confirmed that Emisar was a separate, stand-alone legal entity.

They claimed to have launched Emisar “to focus on negotiating rebate agreements with pharmaceutical manufacturers and developing manufacturer-facing technology solutions,” as well as providing “innovative data analytics services.”

But despite Irish offices, no entity named Emisar was registered to operate in Ireland, according to the Irish business database.

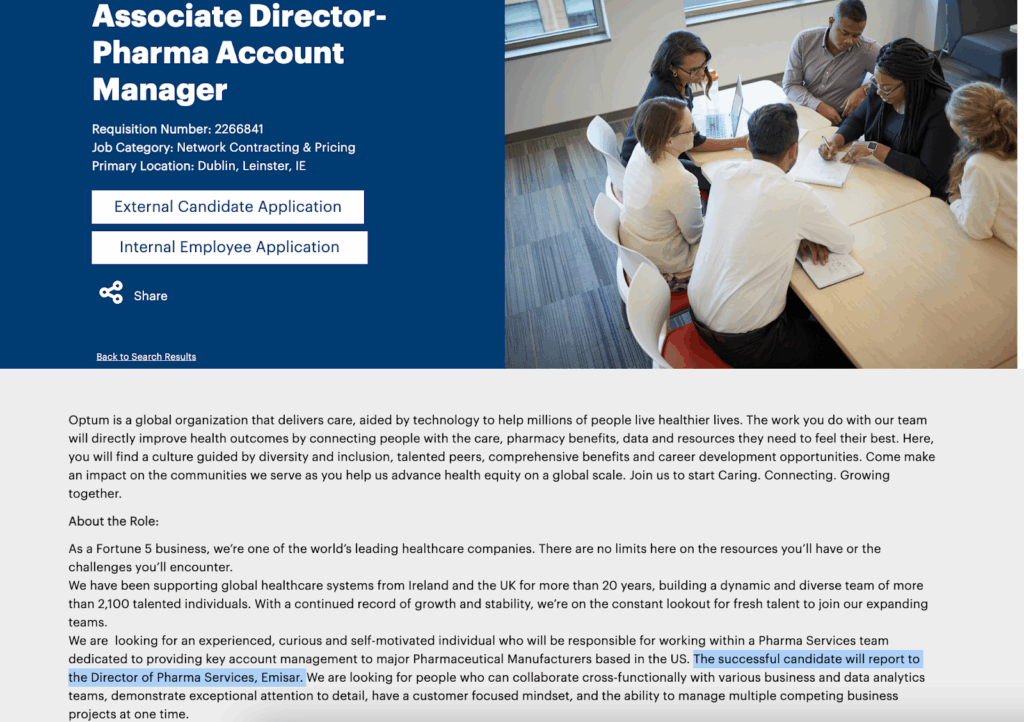

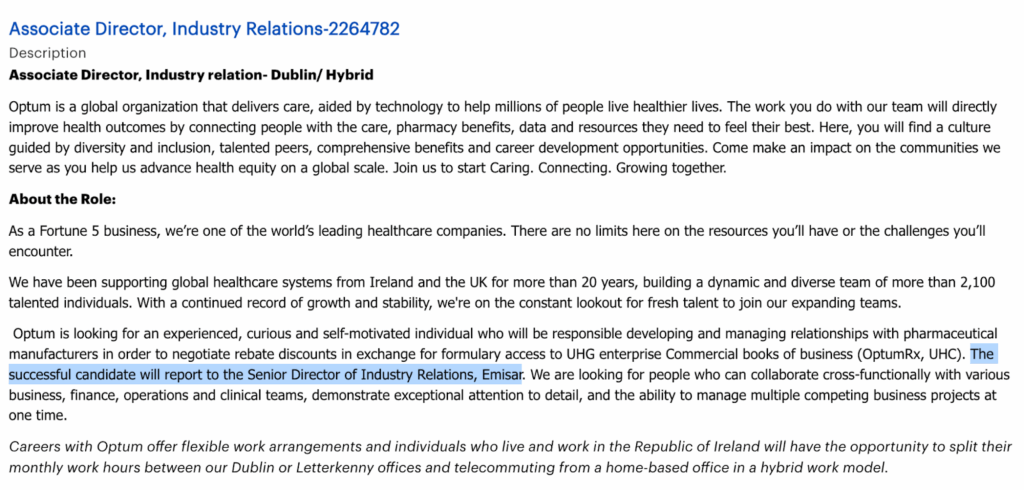

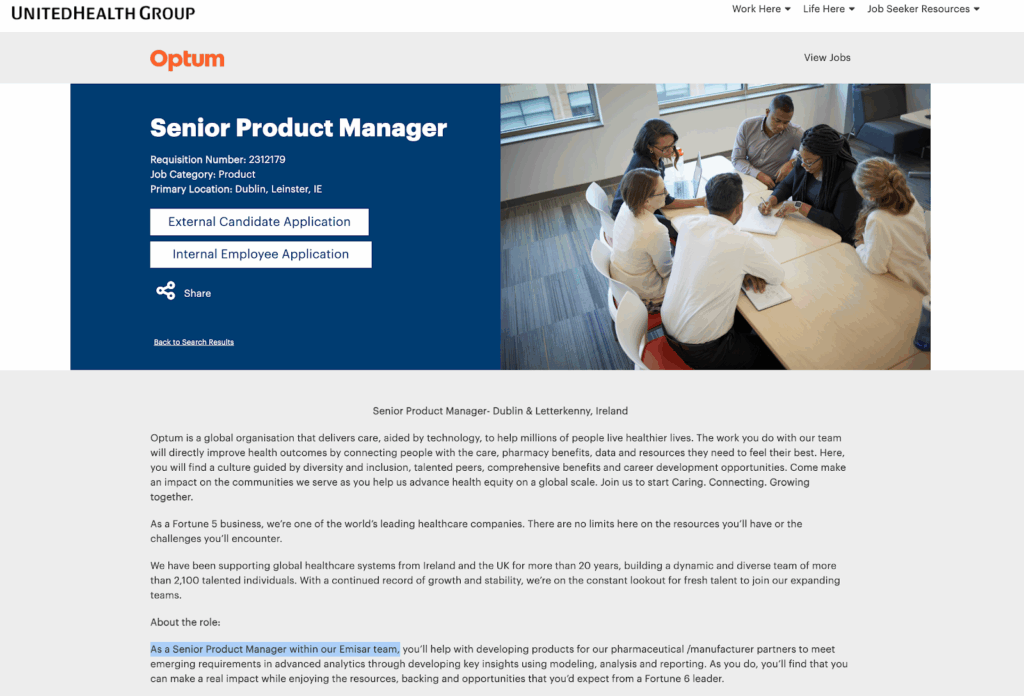

Emisar also appears to lack a website or phone number. It only has about two dozen employees on LinkedIn. And its job openings intermingle with those of UnitedHealth and Optum, suggesting it may not be a particularly independent operation.

The Optum roles of “Pharma Account Manager” and “Associate Director – Pharma Account Manager” both “report to the Director of Pharma Services, Emisar.”

A job posting for an “Associate Director – Industry Relations” at UnitedHeath would “report to the Senior Director of Industry Relations, Emisar.” There’s also a posting for a “Senior Account Manager” role at Optum “within our Emisar team.”

A visit to UnitedHealth’s Optum headquarters in Dublin somewhat clarified the situation.

During a workday in January 2025, an Optum security guard escorted a Hunterbrook reporter through the Optum office building to what appears to be Emisar’s global headquarters, to the extent it exists.

A single room in the Optum building.

An Emisar logo by the door.

About 10 cubicles.

That room — from which Emisar supposedly negotiates billions of dollars of discounts, while also purportedly selling drugmakers a wide array of data, analytics, and administrative services in exchange for massive fees that UnitedHealth claims are not Optum rebates requiring pass-through to health plans, and certainly not kickbacks — was empty.

No one was working there.

Photographs of Optum’s Dublin, Ireland, office by Hunterbrook contributor Doug Donovan, who investigated healthcare fraud for The Baltimore Sun, which won a Pulitzer Prize related to his reporting. Source: Doug Donovan for Hunterbrook Media

“Emisar, which operates out of Ireland, was established in 2021 by Optum and it still doesn’t have a website. When you look at Ireland registered entities, it doesn’t exist. You can hardly find any employees on LinkedIn. Something feels way off here,” Baker told Hunterbrook.

“Emisar is acting behind the scenes on behalf of UnitedHealth Group’s OptumRx PBM. They do not serve any other PBM or external members. If Emisar is adding so much value, why isn’t it actively pursuing other customers?”

Criticizing similar remarks Baker made while testifying before Congress in 2023, On pg. 32 of the hearing transcript, Baker is quoted saying, “These GPOs were established, two of the three, overseas. If you go online and you look on LinkedIn, I have never been able to find more than 30 people associated with these big three GPOs, and they are bringing in close to $200 billion a year in revenue for three entities.” a longtime PBM GPO executive told Hunterbrook, “He’s calling out the problems, I don’t think he’s bringing the solutions.”

On UnitedHealth’s fourth-quarter 2024 earnings call, Witty insisted, “We are committed to full transparency” — but never mentioned Emisar. When Witty was the CEO of GSK, the global drugmaker, he said in a 2017 earnings call: “I think there needs to be a better balance in the system than there is today. There needs to be more transparency. … of $100 paid to an innovative drug company, only $63 on average makes it through to the company, so that is $37 out of the $100 being paid to non-innovators in a system which thinks it is paying high prices for innovation.”

The CEO of Optum posted a LinkedIn message echoing his boss, Witty, promising to “make more transparent who is responsible for drug prices in this country.”

Many of the comments on the Optum CEO’s post were harsh critiques of the PBM.

“Claiming that nearly 100% of rebates are or will go to customers is a twist of words,” wrote Nicolas Ferreyros, who runs a nonprofit that advocates for cancer patients.

“And what about the offshore GPO $$$?” asked Mike Sharp, a pharmacist and industry consultant with SharpRx Pharmaceutical Consultation Services.

Sharp added in an interview with Hunterbrook: “It’s a shell game by PBMs to scrape more money.”

“Are you also going to clarify that ‘non-rebate cash flows’ from pharma will also be passed through? And that this includes the cash flows wrt Emisar?” posted Jens Thorsen, who runs a business that advises health plans on their policies and interactions with PBMs.

In an interview with Hunterbrook, Thorsen called the PBM GPOs a “bait and switch” to hide revenue from PBM contracts. “This is bullshit, they’re passing through some but not others.”

The conclusion: Emisar appears to be essentially a front for Optum and UnitedHealth.

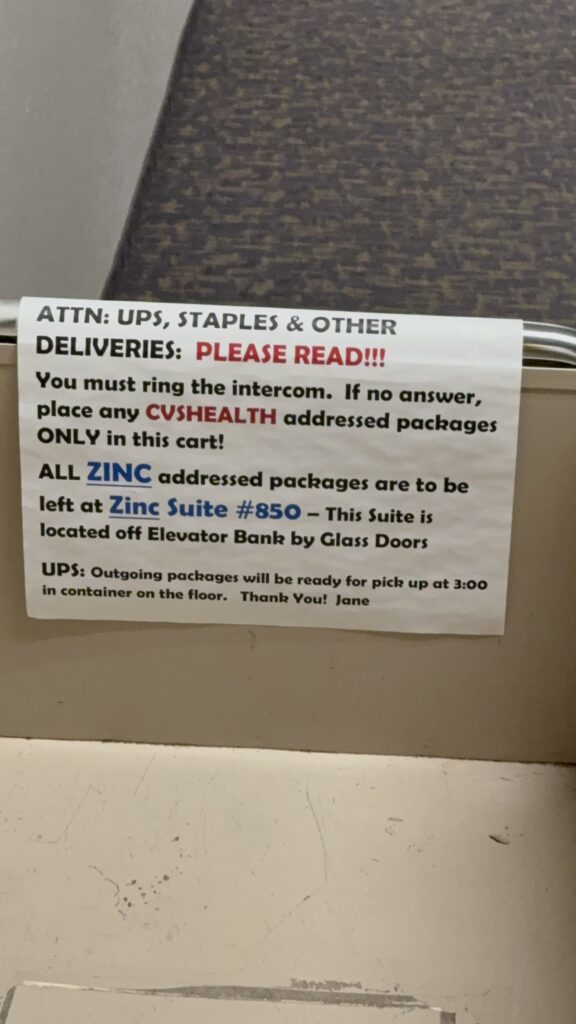

Zinc — owned by CVS Caremark: Firewall? Or No Wall?

Like Emisar, Zinc does not appear to have a website or phone number.

According to LinkedIn, Zinc may have even fewer employees than Emisar.

And its headquarters — whose address was revealed in a lawsuit — turned out to be a single, empty suite in an office building outside Bloomington, Minnesota.

Image of the office building in Bloomington, Minnesota, that purportedly houses the Zinc headquarters. Source: Google Maps

“It looked like a caricature of a front,” said the Minnesota-based singer-songwriter Raffaella, who visited Zinc at Hunterbrook’s request during two separate workdays in early 2025.

She interviewed two CVS employees from the adjacent office, who said they did not know anyone who worked at Zinc.

Was anyone ever at Zinc?

“Occasionally,” said one. “Here and there.”

“They keep it locked,” said the other. “If you’ve got information we can email them … I don’t think there’s a general email, but if you’ve got your information, I’d be happy to pass it along to them.”

“It’s walled off from us.”

Both claimed not to know what Zinc does, or how a person would make an appointment, given the absence of a phone number or an email for Zinc, which could only be contacted through CVS.

A former Zinc executive also employed by CVS Caremark explained the dynamic, requesting anonymity due to risk of retaliation.

They corroborated what numerous industry insiders told Hunterbrook: CVS carefully guards information about Zinc, often intimidating current and former employees to keep quiet.

“Other people at CVS may be scared to talk to you. Leadership, especially Caremark, is very heavy-handed, will threaten them if they say anything publicly negative about the company. They may try to do something via the PBM formularies.”

The former executive scoffed at the healthcare conglomerate’s claim of separation.

“You really don’t know a PBM from a GPO because there is no difference,” they said. “Think of the PBM/GPO as one entity … there was literally a temporary wall put up between Zinc and Caremark. No separate building. … Zinc and Caremark reported to the same VP.”

The purpose of Zinc, they explained, was to rack up charges from drugmakers. “Nobody knows how they broke those monies out, how much the GPO kept, how much was passed to plan.… It was all on paper and it was all transactional money flowing through contracts, there was nothing I had to send to you or sell to you, here buy 500 of these. It was access to the formularies.”

The best example was making drugmakers pay Zinc for data access. They described how the conversation went with drugmakers.

“‘I don’t need it, I don’t want it,’” the drugmakers would say. And in return, Zinc would threaten to “disadvantage you versus your competitors.”

“Will you buy it? Yeah. Do you use it? Probably not,” they said of drugmakers, adding, “If you’re not compliant, they’ll try to disadvantage you versus your competitors. … This is Caremark, Express Scripts, Optum, they all do that.”

They also noted that the charges would increase year over year — with data portal fees quadrupling — despite the fact that “the data was not, in my opinion, very useful from a pharma perspective. … It was minimal.” “Data portal fees, started off charging like .5% then 1% then 2% and if you don’t participate they disadvantage you … not to participate in the data they’ll only pay .5% that means they’re gonna get on a lower formulary tier, disadvantaged.”

What about Ascent?

Ascent — owned by Cigna’s Evernorth Express Scripts

The takeout shack didn’t open until 11 a.m., local Swiss time.

Next door, on the fourth floor of a small office building about an hour from Zurich, a subsidiary of a subsidiary of a subsidiary of the American conglomerate Cigna had its headquarters: Ascent Health Services.

Ascent appears to be the most established of the PBM GPOs — employing about 88 people, according to LinkedIn, and potentially a handful more, according to an office visit. But it’s still a tiny slice of its parent Evernorth Express Scripts, which has tens of thousands of employees.

“Small Company Feel, Big Company Benefits,” reads Ascent’s website. (This one has a website, unlike Emisar or Zinc.)

“We have the energy and boldness of a startup and the expertise and pragmatism of a scale-up, all in one place,” reads another section.

“We are a boutique rebate contracting organization,” reads a third.

An industry expert questioned the branding.

“Isn’t that the exact opposite of their argument now?” asked Sherman. “‘You don’t want a boutique, you want scale.’ It seems like bullshit.”

“I used to do my own rebates at Harvard Pilgrim. I didn’t want to give them up because I didn’t trust the PBMs,” recounted Sherman. Speaking figuratively, he continued: “They came in and put a gun to my head with our CFO and said: ‘Your guys want to keep this because they like doing it, but we have scale.’ We were the boutique contracting shop in that case.”

“In my opinion, it’s corporate fiction,” said Ann Lewandowski, a whistleblower and fractional compliance officer for health plans. Lewandowski founded the consultancy Healthcare Rebel Alliance to help employers improve oversight and compliance of their medical and pharmacy benefits.

Thorsen, the healthcare insurance advisor who had said, “This is bullshit” — referring to the fees collected by PBM GPOs from pharmaceutical companies — was especially skeptical of the Swiss headquarters.

“If there’s a good explanation that’s not sheltering cash, I’ll be darned.”

Looking for that explanation, a Hunterbrook reporter visited Ascent’s headquarters in Schaffhausen.

In the elevator to the office, a postman had a package for Ascent.

Did he deliver to Ascent often? “No, not regularly, not so much.”

A receptionist at Ascent took the package and walked the reporter through the open floor-plan office past a dartboard to the kitchen for a glass of water. She confirmed Ascent had the entire floor and guessed the company numbered “maybe about a hundred” people.

How many came to the office?

“It really depends. Just a few,” she told Hunterbrook.

That day, it appeared to be about a half-dozen, between the office visit and observation from the outdoor patio of the neighboring takeout shack.

“I started with just kebabs and donuts. Now I have more. And different sauces,” said Ahmed, the proprietor of Albeek Take Away.

Did he have any customers from Ascent?

“No, no, no, from Ascent, nobody,” he said. He pointed at two other small offices in the area. “I get people from there and there, not there,” he said, pointing back to the Ascent office.

Did he ever deliver to Ascent?

“No, no, no delivery.”

At the closest café, the barista, Chiarra, recognized the name Ascent, though she said she did not have any regular customers from the office.

“They order from here once or twice a month,” she said.

By 5 p.m., Ascent had called the police on the Hunterbrook reporter at the outdoor patio of the takeout shack.

Two Polizei approached, saying that Ascent had called “a couple of minutes ago.”

One officer, Ismail Scheuermeier, stayed with the reporter at the shack while the other went up to Ascent.

Scheuermeier asked about the reason for Hunterbrook’s investigation, then shared his own perspective on the healthcare system.

“We think it is stupid in America,” he told Hunterbrook. “Our medicine is also expensive … But as a regular working man or woman, it is affordable, you do not end up on the street,” he said, referring to the Swiss healthcare system. “In America there are people on the street. Someone gets cancer they end up on the street. You hear about it in the media, in movies. Not many positive things.”

“We think it is stupid in America … Someone gets cancer they end up on the street. You hear about it in the media, in movies.” —

A Swiss police officer called by Ascent, the offshore subsidiary of Cigna and Evernorth/Express Scripts, to check out a Hunterbrook reporter

The other police officer returned with two men from Ascent. Both declined to share their names.

“That’s not relevant,” replied one of the men, who later confirmed via LinkedIn that he was Ascent’s chief commercial officer. According to LinkedIn, the CCO previously worked for Cigna’s Express Scripts from Orlando, Florida, before moving to Switzerland in 2022.

In response to hearing about the empty Emisar office in Dublin, he said, “We are not a fake company, there are ways for press to reach us.”

But there was no press contact on Ascent’s website. The “Contact Us” link didn’t work on certain browsers. And after initially offering to share a corporate contact, the Ascent executive instead asked for a Hunterbrook contact.

The next day, the U.S.-based managing director of external affairs for Cigna followed the reporter’s public account on X and sent a request to follow the reporter’s private Instagram account.

In response to a follow-up request for comment through LinkedIn, the CCO referred to Ascent and Cigna jointly as “our company.”

“It is our policy that all media inquiries about any and all aspects of our company be referred to our media relations team which has a publicly available email address. The email address for media relations is on the Cigna website.”

During the conversation outside the Swiss office, the Ascent executive said he’d called the cops because of concerns raised by the December 2024 killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, allegedly by Luigi Mangione.

“Look, with everything that’s been going on, you know, the shooting in New York, and you come here this morning, then disappeared for a few hours, and then you’re back,” he said. “And we’ve got anxious people here. Look, I hope you won’t come back again and try to talk to people.”

The reporter offered not to return if they’d answer a couple of questions. What was the purpose of this Swiss subsidiary, and were he and his colleague from America?

“We work at Ascent, that’s all I’ll say,” he replied.

The police officer wrapped up the impromptu interview, asking that the Ascent executive share a contact email and Hunterbrook write to that email rather than returning to the office.

The officer concluded, “There are many other beautiful things to see in Schaffhausen.”

One proved to be the newsroom of the regional business paper AZ, which investigated the proliferation of the “many letterbox companies in Schaffhausen,” as an AZ journalist called the local shell companies.

The journalist pulled a copy of Ascent’s filings from the town’s commercial registry, dating back to Ascent’s incorporation in April 2019. Ascent’s many signatories are almost exclusively American and include Amy Bricker, the former president of Express Scripts.

“The 8:05 a.m. train from Zurich to Schaffhausen is full of Americans every morning, big sign of this small town as U.S. tax haven,” the journalist said.

A former employee of Ascent contradicted this purpose. “From here it looks like shifting money,” they told Hunterbrook, requesting anonymity to avoid retaliation. “They move money here and there.”

Ascent has the strongest case for being an actual “group purchasing organization” — PBMs beyond Express Scripts, including a PBM called Prime Therapeutics, are publicly involved in Ascent.

Offshore PBM GPOs like Ascent and Emisar are particularly worrisome to Alden Bianchi, an attorney at McDermott Will & Emery LLP who advises large employer group health plans.

“There’s just zero transparency with the cross-border cooperatives,” he said, referring to Ascent and Emisar.

“There’s no broker disclosure law, for example, that requires them to tell you what’s going on. So I view them with a good deal of suspicion, especially if you are a fiduciary of a plan, which a lot of my clients are,” Bianchi continued.

“How do you possibly exercise your fiduciary duty over some oversight when you’re dealing with an offshore cooperative?”

The broker disclosure law Bianchi mentioned is part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, which implemented transparency and reporting requirements for employer-sponsored health plans and the vendors that deliver these benefits.

Were taxes the reason for the Swiss jurisdiction?

“Yes, it’s nothing else,” a former Ascent employee told Hunterbrook.

Miller, the Ascent co-founder, independently confirmed the tax advantages.

“We had a skunks team that looked at all the regulations and tax implications,” he told Hunterbrook, referring to a team within the overall Cigna/Express Scripts organization that helped create Ascent.

“There’s obviously the advantages of being offshore also.”

After starting out as a physician, Miller became the chief medical officer of his hospital system and then joined Express Scripts when the PBM had just begun scaling up.

He was widely credited for his pioneering work to dramatically reduce the price of statins, which are essential to tens of millions of people. Early in his career at Express Scripts, he challenged Pfizer — then the largest pharmaceutical company in the world — and stripped Pfizer’s blockbuster drug Lipitor from his PBM’s formulary, favoring a more affordable generic.

Miller later took on Martin Shkreli — the felonious pharmaceutical executive who notoriously hiked the price of antiparasitic medicine Daraprim from $13.50 to $750 per pill. Miller partnered with a compounding pharmacy to undercut Shkreli with a $1 alternative.

In other words, Miller embodied what PBMs were originally meant to do: reduce healthcare costs.

When Cigna acquired Express Scripts, Miller became the chief clinical officer of both companies.

“I spent an enormous amount of time fighting inevitable regulations, legislation, and sort of hatred in the marketplace,” he told Hunterbrook. Miller continued: “Pharmaceutical manufacturers have essentially painted the PBMs as the root cause of all evil and all high prices. The retail pharmacists have done the same thing, and they’ve flooded the airwaves, and over the last three years or so, they’re now winning the day. They’ve gotten patients mad at them, clients mad at them, legislators, regulators, et cetera. And so, while they still have a stranglehold on the market, their Achilles heel is not so much that a new model would disintermediate them as much as legislators, regulators are going to disintermediate them. Perhaps.”

This onslaught led to the creation of the PBM GPOs.

“Hand-in-glove to the whole conversation of how do you sustain your profitability over time is you’ve just got to continually be evolving new things,” he told Hunterbrook.

Miller explained that a core benefit of the PBM GPOs is that they can charge fees that are not considered rebates, and therefore do not need to be passed through to health plans and patients.

“There are lots of different fees you can charge. You can charge data fees. You can charge administrative. You can charge clinical fees. The fees fall into different buckets,” he explained.

“You can double-, triple-dip on fees.”

“This is why there’s so much hatred now, because as these details become more known, people are like, what a screwy business this is, right?”

Baker of AffirmedRx elaborated on the kinds of “details” Miller was referring to.

Baker showed Hunterbrook an example of an Express Scripts client letter that displayed a single number, versus the itemized breakdown AffirmedRx provides in its pursuit of differentiation through transparency.

He said AffirmedRx had identified 23 different sources of fees charged by PBM GPOs. “All of these fees add up and there is no accountability or visibility,” Baker told Hunterbrook.

Countering that criticism, Miller argued that PBMs are probably necessary to rein in drug pricing by drugmakers. “When the pharmaceutical manufacturer sets its price, if the PBM did not exist, would they set the price any lower?”

Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs is already testing this hypothesis, cutting out PBMs by selling drugs directly to consumers – and contracting directly with employers.

Were Ascent’s fees adding profit on top of what could be taken from rebates, or were drugmakers adapting by reducing the rebate payment as they paid Ascent more?

“They were reducing rebates to pay Ascent more,” Miller said, confirming the core issue: Health plans were getting less money because of payments to PBM GPOs.

This was, Miller explained, the nature of the PBM business: facing off against the consultants hired by the health insurance plans to review bids by the PBMs.

“When you’re dealing with these PBMs, they’re much more aggressive, smarter people, a little more creative,” he said. “It’s a pretty sharp-elbowed business.”

“When you first create something, you’re trying to get ahead of the consultants and their knowledge, right? So when you initially set up an Ascent, they’re unaware of this,” Miller said, apparently indicating that the PBM GPOs were at least in part deceiving the health plans and their consultants.

“Nothing stays quiet for long. Someone starts understanding, oh, there’s this new pool of money, so we’re going to put it in our contracts to cover that also. And so it’s a whack-a-mole thing. And this is why consultants are involved in almost every bid.”

Referring respectively to health plans, consultants, and PBMs, Miller said: “Because you’re [health plans] paying them [consultants] essentially to try to understand where’s the next innovation of how they’re [PBMs] going to try to rob me [health plans].”

“Once it gets discovered, the consultants narrow in on it, you end up disclosing more and more,” Miller concluded.

“It seems like bullshit.” —

Michael Sherman, former chief medical officer of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care

The Numbers: Millions of Dollars in Revenue per Employee

Despite the ghost offices, tiny head-counts, and opaque operations, a staggering amount of money flows through these subsidiaries.

Hunterbrook reviewed LinkedIn profiles, team photos, corporate filings, and job listings to determine the staffing at all three entities. We identified fewer than 150 employees total — about 88 at Ascent, and roughly two dozen each at Emisar and Zinc. Hunterbrook identified LinkedIn profiles of current employees for all three PBM GPOs. Ascent had a company page, which facilitated clearer estimates of its workforce, but neither Zinc nor Emisar had websites or LinkedIn pages. Due to these limitations, we used generous criteria in identifying profiles for classification as Emisar and Zinc employees. Accordingly, the true revenue per employee is likely even higher than our estimated ~$50 million per employee.

These skeleton crews apparently handle billions of dollars a year.

Neither the PBM GPOs nor their parent companies report financial information for these specific entities, but the limited data available suggest these businesses are improbably lucrative.

A 2023 Nephron Research report cited by the FTC estimates PBMs earned $7.6 billion in fees related to their GPOs in 2022. With fewer than 150 employees across all three entities, these PBM GPOs generate more than $50 million in revenue per employee. By comparison, Apple — long considered one of the world’s most profitable companies — generated approximately $2.4 million per employee in 2024. Nvidia, the AI chip giant whose market cap has surpassed $4.5 trillion, brings in about $3.6 million per employee.

This napkin math was backed up by the former Optum and Emisar executive Rogers, who estimated to Hunterbrook that the GPOs bring in at least “tens of millions” per employee.

The persistent lack of transparency surrounding PBM GPOs makes it difficult to untangle any value they may be adding, according to Ben Link, a pharmacist who previously worked for a PBM and now leads 46brooklyn and 3 Axis Advisors alongside Ciaccia.

“When these GPOs were created, was there a transfer of assets into the GPO? Like, either they actually did develop something, or from an account management standpoint, there would have had to have been a transfer of assets, right?” Link posited. He added, “Because, again, if you didn’t do those things, well, that would certainly seem to suggest more so, again, this is a shell, right? This isn’t actually doing anything. There’s no unique value here, aside from slip slapping a label on it.”

Ciaccia and Link have worked with states to identify problematic PBM practices, including a major 2018 investigation revealing nearly a quarter-billion dollars of margin PBMs made from the Ohio Medicaid program unrelated to GPOs. The state cut ties with PBMs based on the findings.

The federal government has looked into PBMs as well. As part of a sweeping investigation of the pharmaceutical supply chain, the FTC sued the Big Three PBMs and their PBM GPOs for inflating insulin prices in 2024. The FTC also specifically flagged PBM GPOs as entities of concern in a July 2024 interim report on PBMs. The report discusses PBM GPOs in detail in Section 2.C. “CORPORATE RESTRUCTURING OF PBM REBATE NEGOTIATION SERVICES RAISES CONCERNS” on pages numbered 21-24; they’re also mentioned on pages numbered 2 and 10-11.

A spokesperson for the FTC declined to comment for this story.

Calling Emisar, Ascent, and Zinc “rebate aggregators,” the FTC found evidence of financial engineering on a massive scale: “Internal PBM documents appear to show novel methods of fee generation from these new rebate aggregators. One report estimates that since the PBMs spun off their rebate aggregators, they have extracted from drug manufacturers billions of dollars in additional fees, which doubled from $3.8 billion in 2018 to $7.6 billion in 2022.”

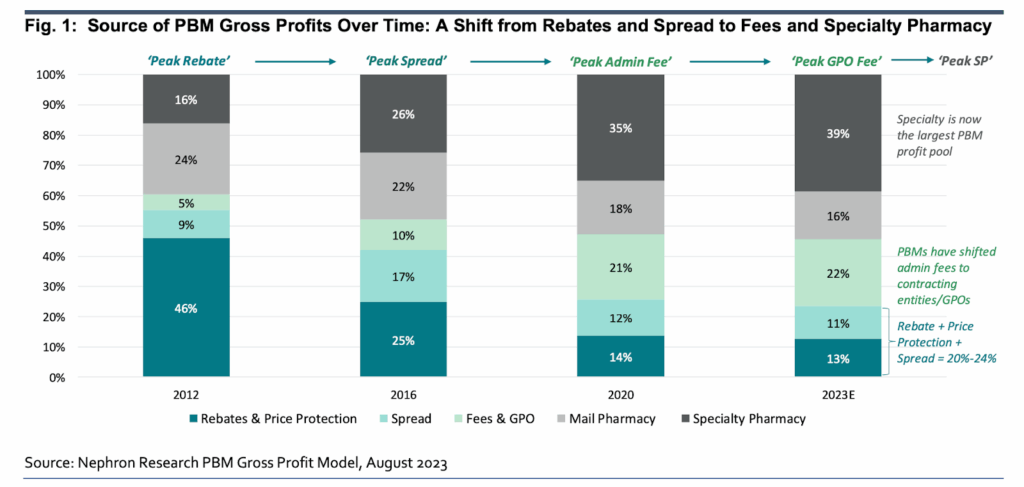

The FTC cited data from Nephron Research, showing that “Fees & GPO” overtook “Rebates & Price Protection” and the “Spread” PBMs collect as a percentage of PBM gross profits. This growth accelerated between 2016 and 2020. That coincided with a proposal by the first Trump administration to remove the safe harbor for PBM rebates from federal anti-kickback laws.

“These aggregator fees have grown substantially since the initiation,” said Sharp. “They’re becoming very material in terms of what pharma has to pay to obtain access to these formularies.”

“They started out as 1 to 2.5% of rebate amounts,” he told Hunterbrook. “The PBMs knew they’d eventually have to be transparent about rebates. They started this side pool to protect their margin and revenue. Now, they’re in the 15-to-20% of total rebate amounts.”

This extraordinary revenue flows through a labyrinth of payment categories sources say are carefully engineered to avoid transparency: entity administration fees, prescription data services, data portals, enterprise fees, and other charges that PBMs insist are not rebates and therefore don’t require pass-through to health plans. These revenue streams exist on top of the PBM’s typical administrative service fees of about 3% to 5% of the wholesale price of each drug, further inflating healthcare costs.

The effectiveness of the scheme is enhanced by its invisibility. Most healthcare payers (health plans, unions, self-insured employers) — and certainly patients — have no idea these PBM GPOs or their fees even exist.

“It’s fight club. First rule of fight club, you don’t talk about fight club,” Link, the pharmacist and former PBM employee, told Hunterbrook, referencing the film “Fight Club.”

“You don’t know what you don’t know, and to the extent the PBMs themselves are delivering what they said, it wouldn’t even occur to a health plan,” said Sherman.

“Even when I was a health plan CMO, I don’t know, barring some shock or data point, how I would figure out that there were tens of millions of dollars that they were sucking up somewhere,” Sherman told Hunterbrook. “I always assumed they were screwing with me somehow, and if you can minimize that, you’re ahead of the game. But I wouldn’t have known how to look for it.”

PBM GPOs Begin Receiving Legal Scrutiny

Beyond the FTC, a few others have begun to wise up to the scheme.

States including Illinois, Ohio, Louisiana, Vermont — as well as the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the United States Office of Personnel Management — have each begun to tackle the PBM GPO scheme. On April 14, 2025, 39 state attorneys general sent a letter to party leaders in both houses of Congress highlighting concerns about PBMs and urging the passage of federal legislation barring PBMs from owning pharmacies.

In June 2025, Louisiana filed a lawsuit against Zinc and Caremark in state court. Shortly afterward, a Hunterbrook reporter contacted the attorney general’s office about a potential error in the company’s name in the complaint. While it declined to comment on or confirm that the flagged text was incorrect, citing “active litigation,” the attorney general’s office re-filed its complaint the next day, correcting the error. On June 23, 2025, the Louisiana attorney general filed a petition identifying “Zurich Pharma Solutions GmbH” as CVS Caremark’s GPO. A Hunterbrook reporter corresponded with the attorney general’s press secretary on June 25 about the case, including an email asking, “I just wanted to confirm if your complaint filed yesterday intended to include Zinc Health Services LLC, rather than Zurich Pharma Solutions GmbH? The entity Zinc Health Services (in Bloomington, MN) is known to be CVS/Caremark’s GPO, whereas the entity Zurich Pharma Solutions does not appear to exist.” On June 26, the attorney general’s office filed an amended petition that replaced “Zurich Pharma Solutions” with “Zinc Health Services.”

Louisiana and CVS Caremark are discussing a settlement, Attorney General Liz Murrill said in December 2025. CVS would pay around $50 million to resolve the lawsuit concerning Zinc, as well as two related cases over Caremark’s practices.

“We can confirm we have an agreement in principle with CVS. The suits will be dismissed, and they are eligible for the discretionary one-year extension as a Managed Care Organization. We will announce the specifics once finalized,” a spokesperson for Attorney General Murrill told Hunterbrook.

In Ohio, the attorney general is pursuing a case similar to the one in Illinois, claiming that Express Scripts used Ascent to fix prices and rebates among a handful of supposed competitors. Ohio alleged: “Ascent has provided a convenient vehicle for Express Scripts, Prime Therapeutics, and Ascent’s PBM customers to aggregate and access each other’s pricing, discount, rebate, and negotiations information” and “act in concert to harmonize their Manufacturer negotiations and demands, effectively eliminating all competition between themselves and further ensuring that they continue to profit from supracompetitive drug prices.” The attorney general’s office did not respond to Hunterbrook’s request for comment.

In April 2025, Michigan’s attorney general accused Express Scripts and Prime Therapeutics of using Ascent as part of an illegal price-fixing cartel.

Prime Therapeutics is a separate PBM with a minority ownership stake in Ascent. Prime’s then-CEO Ken Paulus described Ascent as a “real shared effort” between the two PBMs in a 2021 interview.

”We have direct access to all of the contracts in the GPO. We have employees that work in the GPO with, with their employees,” Paulus said. He noted that, at the time, Ascent represented “100 million lives” and had generated “literally in the billions of dollars of, I think, savings for our clients that we wouldn’t have otherwise seen.”

Prime Therapeutics declined to provide comment for this story.

Rather than compete against each other, Express Scripts and Prime Therapeutics agreed to leverage their combined buying power to undercut independent pharmacies in the state — leading to “pharmacy deserts” and bolstering Express Scripts’ market power, according to the Michigan attorney general’s complaint.

“To effectuate the Agreement, Prime and ESI exchange CSI — including the confidential terms of their contracts with retail pharmacies and drug manufacturers — in part through a secretive, off-shore, jointly-owned group purchasing organization (‘GPO’) called ‘Ascent,’” read the complaint.

Meanwhile, there’s been pushback at the federal level.

In August, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform opened a probe into Emisar and Ascent. The creation of offshore GPOs “appears to be yet another example of the institutional intent at opacity and avoidance of oversight within your company,” read the letters sent to Cigna and Optum Rx.

The Committee’s Majority staff did not respond to repeated Hunterbrook inquiries about the status of the probe. PBM executives have faced heated exchanges and aggressive grilling during Congressional appearances in recent years. Last summer, Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer, a Republican from Kentucky, suggested the leaders of Caremark, Optum Rx, and Express Scripts may have perjured themselves in Congressional testimony, threatening fines and jail time.

Federal watchdogs have also been clawing back funds from PBM GPOs.

In March 2024, the Office of Personnel Management reported on its audit of pharmacy benefits administered by Express Scripts, which had been hired by the American Postal Workers Union Health Plan. According to the report, the union was supposed to receive “‘the value of the PBM’s negotiated discounts.’”

But in 2019, Express partnered with Ascent to “handle all drug manufacturer rebate administration.” Now, the PBM and GPO split drug company rebates between them. When the time came to pass through the money, Express sent along its share — but Ascent didn’t. Instead, it pocketed about $15 million that should have gone to the union.

The PBM GPO agreed to return the $15 million. But their counsel insisted Express Scripts “contracted with Ascent to perform rebate management services,” and the payment was a good faith measure. (The letter was included as Appendix B in the OIG Final Audit Report.) Express Scripts argued: “It is our understanding that throughout the audit process, ESI reiterated that its operations were appropriate and compliant under the Agreement, however, understood that OIG took the position that contracting through Ascent for this short period of time without providing a monetary adjustment was inadequate. While contractual interpretations may vary, given its commitment to its FEHB customers, ESI voluntarily agreed to credit the amount to APWU rather than contest OIG’s position, and will also credit LII upon validation of the calculated amount.” FEHB refers to Federal Employee Health Benefits, ESI is Express Scripts, APWU is the union, and LII stands for lost investment income.

Later in 2024, the Office of Personnel Management had déjà vu: Its audit showed Ascent had kept nearly $10.6 million in rebates it owed the Compass Rose federal employee health plan. Once again, the contract apparently required “pass-through transparent drug pricing” so the plan would “receive the value of the PBM’s negotiated discounts, rebates, credits, and other financial benefits.”

Yet, millions in rebates were withheld from Compass Rose because of “lower rebate percentages agreed to internally between the PBM and Ascent,” according to the OIG’s Audit Report.

Ascent kept 14.264% of the total rebates it received for Compass Rose from mid-2019 through 2021. “As a result, we asked the PBM to identify the rebate amounts withheld by Ascent for the period of June 1, 2019, through December 31, 2021.” … “The PBM provided evidence showing that Ascent collected $70,382,646 in rebates for the Carrier and the FEHBP, but only passed-through $60,343,427, resulting in an underpayment of $10,039,219 to the Carrier and the FEHBP.” Calculation: $60,343,427 / $70,382,646 = 85.736% pass-through, other 14.264% retained by GPO.

Express Scripts agreed to credit Compass Rose for the rebates it wrongfully withheld, once again insisting that Ascent is not its “sister company.”

“Of the few that have raised the issue, they’ve immediately caved,” said Sherman. “Why would you think that any health plan is not subject to the same gaming?”

“I think they exist for the sole purpose of hiding data and taking fees,” Jonathan Levitt told Hunterbrook, referring to PBM GPOs.

Levitt is a founding partner of Frier Levitt LLP, a healthcare law firm. He provided testimony on PBM GPOs to the Senate Finance Committee in 2023, and his firm has helped plan sponsors recover millions of dollars PBMs wrongfully diverted to rebate aggregator GPOs.

He told Hunterbrook it is a fiduciary responsibility for plans to audit PBMs, and if the health plan finds underpayment, a fiduciary responsibility to recover it. “If you do an audit, and you’re in the middle of an RFP, I almost guarantee that you will get better terms in the next contract.”

“The manufacturer contracts with the GPOs that we’ve seen reveal a delta between what the plan received and what the manufacturer paid,” he said. “We’ve seen GPO manufacturer agreements that discuss the administrative fees and other fees that the PBM contract with the plan does not mention.”

Zinc, Emisar, and Ascent have also been looped into major multi-district litigation against PBMs, insurers, and pharmaceutical companies for driving up the price of insulin. Over 400 companies, unions, school districts, universities, and state and local governments have signed onto the suit as plaintiffs.

Last January, the plaintiffs moved to add the PBM GPOs as defendants.

Similar drug pricing lawsuits are making their way through state and federal courts, including cases filed by the attorneys general of Hawaii and Rhode Island.

Critics of rebates and high drug prices had only just begun sinking their teeth into PBMs when the conglomerates began ramping up these PBM GPOs. They get just a cursory mention on three pages of the 73-page interim report the FTC published in 2024. The FTC included the Big Three PBMs and other major players: Humana Pharmacy Solutions, MedImpact Healthcare Systems, and Prime Therapeutics, which owns part of Ascent. These six companies control 90% of the market, representing the vast majority of American health plans.

In a brief section about PBM GPOs, a subheading reads: “Corporate Restructuring of PBM Rebate Negotiation Services Raises Concerns.”

Those were the government’s core findings before the 2024 election. “FTC staff has engaged in ongoing negotiations with these entities regarding their required productions of documents and data, with some stating that they currently do not anticipate completing productions until 2025,” wrote the FTC.

PBM GPOs got slightly more attention during listening sessions hosted by the Department of Justice and FTC this summer.

“The largest PBMs created new GPO structures under their own parent companies that are now offshore, primarily in places like Switzerland and Ireland, that negotiate rebates on behalf of almost every patient in the country, at least in commercial markets,” said Joe Shields, founder and president of TransparencyRx. “That’s not reform, that’s not meaningful transparency or market integrity.”

“You can imagine how many times I’ve been physically to the FTC,” said Miller, the former Cigna and Express Scripts CMO. “The PBMs underestimated the problem that was going to create.”

In January 2025, the Trump administration fired the inspector general who had recovered $15 million for the postal workers union and $10 million for other federal employees from Cigna’s Express Scripts and Ascent.

In March 2025, Trump fired the two Democrats of the five-member FTC leadership, leaving the agency without a single commissioner able to oversee the FTC’s insulin lawsuit. Former Commissioners Alvaro Bedoya and Rebecca Slaughter sued the Trump administration alleging illegal termination. The Supreme Court stayed a lower court order letting Slaughter resume her post while the litigation plays out, and heard the case in December. Bedoya is no longer seeking reinstatement to his post, though he maintains that the firings were illegal. Their lawsuit is based on a 1935 Supreme Court ruling that said a president cannot remove FTC Commissioners for political reasons, but only for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.”

As a result, the case was administratively stayed from April 1 through August 27.

Lina Khan, the chair of the FTC at the time the lawsuit was filed, called the firings “A gift to the PBMs.”

Express Scripts accused Khan of having an “anti-PBM bias” when they sued the FTC last fall, alleging the FTC’s July 2024 report on the industry was “unfair, biased, erroneous, and defamatory.”

A month after the proceedings resumed, the FTC’s case was once again put on hold for all of October and most of November, thanks to the month-and-a-half-long government shutdown. An evidentiary hearing is currently scheduled for June 17, 2026.

The PBMs and their GPOs are seeking to have the case dismissed. They’re also challenging the FTC proceeding in federal court as unconstitutional.

Some states are attempting to rein in the PBMs and their GPOs through legislation. In October 2025, California enacted a PBM reform package that decouples PBM compensation from drug prices in favor of a flat fee model and requires rebate pass-through, among other provisions. The law explicitly specifies that rebates include any discounts or fees collected by an affiliated GPO. The bill text amends Section 1385.001 of the Health and Safety Code to read:

“(v) (1) ‘Rebates’ means compensation or remuneration of any kind received or recovered from a pharmaceutical manufacturer by a pharmacy benefit manager, affiliated entity, or subcontractor, including a group purchasing organization, directly or indirectly, regardless of how the compensation or remuneration is categorized, including incentive rebates, credits, market share incentives, promotional allowances, commissions, educational grants, market share of utilization, drug pullthrough programs, implementation allowances, clinical detailing, rebate submission fees, and administrative or management fees.

“(2) ‘Rebates’ also includes fees, including manufacturer administrative fees or corporate fees, that a pharmacy benefit manager, affiliated entity, or subcontractor, including a group purchasing organization, receives from a pharmaceutical manufacturer.

“(3) ‘Rebates’ does not include pharmacy purchase discounts and related service fees a pharmacy benefit manager, affiliated entity, or subcontractor receives from pharmaceutical companies that are attributable to or based on the purchase of product to stock, or the dispensing of products from a pharmacy benefit manager’s affiliated mail order and specialty drug pharmacies. ‘Rebates’ does not include a pharmacy benefit management fee.”

PBMs Fail To Disclose PBM GPOs in Contracts with Health Plans

Hunterbrook reviewed several contracts between health plans and each of the Big Three PBMs — Optum, Express Scripts, and CVS Caremark — as well as marketing materials presented to PBM clients.

Across thousands of pages of contracts and presentations, the PBMs did not include any direct explicit mentions of Emisar, Ascent, or Zinc whatsoever.

“They’re hiding it contractually,” said Sharp, who was instrumental in establishing the CMS NADAC system for tracking pharmacy prices and who helped implement Indiana Medicaid’s supplemental rebate program while pharmacy director for the state’s Medicaid plan. He added, “If I were contracting and I created this aggregator pool, would I really want to tell anybody about it? Probably not.”

Thorsen, the health plan consultant, agreed: “There were other cash flows hidden that were not getting passed back.”

“When I last met with them, it was not on the radar,” Sherman, the former CMO of Harvard Pilgrim, said of his meetings with PBMs, and any mentions of PBM GPOs. “They didn’t differentiate between the PBMs and the companies that were a level down,” despite fiduciary responsibilities and transparency laws.

Certain contracts claim 100% pass-through of rebates to the client. But they limit the scope of rebates, similar to the statement by former UnitedHealth CEO Sir Andrew Witty on the aforementioned earnings call. “They started small. They started out as 1-2.5% of rebate amounts,” said Sharp. “The PBMs knew they’d eventually have to be transparent about rebates. They started this side pool to protect their margin and revenue. Now, they’re in the 15-20% of rebate amounts.”

PBMs generally don’t consider the new “fees” drugmakers pay to their affiliated PBM GPOs to be rebates. Because contracts are between PBM and plan sponsor (not the PBM GPO and plan sponsor), PBMs can argue that their clients are only entitled to rebates that actually hit the PBM’s account.

Consider a hypothetical example:

Company A hires Caremark to be the PBM for its employee health plan. The contract says Caremark will pass through 100% of rebates received by the PBM in relation to claims by Company A’s plan members.

Zinc receives $100 million in total payments from drugmakers for patients on Company A’s health plan. Zinc sends $80 million of this to Caremark, keeping $20 million that it classifies as fees or other GPO compensation. Caremark passes through $80 million — 100% of the rebates Caremark received — to Company A.

The other $20 million belongs to Zinc, not Caremark, even though the funds still ultimately pad the bottom line of their shared parent company: CVS Health.

And because Company A only has a contract with CVS Caremark (not Zinc), Company A has no way to know about the $20 million Zinc kept.

“Rebates have become a term of art, and in the old days we would characterize any money from pharma as rebate,” according to Ciaccia. “They’re now being re-itemized as associated fees along with rebates, even though they may, in fact, walk and talk just like the rebates of old.”

“You’re looking at a business model that, in general, is contorting itself to try and make old money in new ways,” Ciaccia said of the Big Three health conglomerates CVS Health, Cigna Group, and UnitedHealth Group.

The contracts that Hunterbrook reviewed also say that the PBM won’t contract with drugmakers for non-rebate revenue that reduces rebates, contradicting the Cigna CMO’s assertion that drugmakers reduced rebates to pay higher fees.

At least one contract also said that the PBM wouldn’t alter a drug’s status on the formulary list of insured drugs based on fee payments, only rebates.

Sharp said his manufacturer contacts “categorized these as bullshit fees,” he told Hunterbrook. “Manufacturers refer to it as extortion for formulary access.”

“My view of these aggregator fees is it’s another way to recategorize that rebate money and create new revenue streams in their contracts with manufacturers,” Sharp continued.

Baker, the CEO of AffirmedRx, echoed this. “Most of the fees are payment for market access, in my opinion. If I’m being generous, only 5% of the fees are for administering those negotiations,” he told Hunterbrook.

Sharp posed the question: “Are rebates being cannibalized by the aggregator fees?”

Former Emisar executive Rogers said, “As the bubble is bursting, premiums have been set for the next three years and there’s not going to be enough rebates to pay them. And so they’re gonna have to raise premiums for employees.”

Rogers added, “There’s no more money left.”

The former executive of a drug company told The New York Times “he had a set pool of money to cover fees to G.P.O.s and rebates to employers. When he paid more in fees, he offered less in rebates.”

Sharp told Hunterbrook, “Your physician, your legislator, people that use the benefit, they don’t understand what the aggregators are, what they do, what they keep, how they affect drug pricing.”

He explained the impact on how much a patient pays for medicine, demonstrating how the majority of drug revenue is pocketed by the various middlemen. Sharp: “Just take brand drug X. Manufacturer sets the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) at $1000. The drug goes to the wholesaler. From the wholesaler it goes to a pharmacy and from the pharmacy to a patient. And then you show a model of a 45% rebate. And then you take another 15-20% of that rebate as an aggregator fee. So, the majority of the $1000 WAC is essentially being scraped off in those two situations right there. 50-60%! So what’s left over becomes the true net price after all that. But people who go to the pharmacy, the basis of their expenditure, if it’s co-insurance or deductible, is the gross list price (WAC).”

Hunterbrook interviewed drug company executives about their interactions with PBMs and PBM GPOs. The CEO of one billion-dollar, publicly traded pharmaceutical company, who is contracted with all three PBMs, described a byzantine process.

“It’s a little absurd,” he told Hunterbrook. “They own the GPO and the PBM of course, so the GPO is sort of a smokescreen to say we didn’t make a decision on the pharmacy benefits, this GPO did.”