Based on Hunterbrook Media’s reporting, Hunterbrook Capital is short $RELY and $WU at the time of publication. Positions may change at any time. See full disclosures below.

UPDATE: This article has been updated to include comments from Grupo Elektra and Banco Azteca.

The scion of a Mexican billionaire suddenly leaned forward from their seat on the private jet.

“You absolutely cannot use my name,” the investor warned.

They then described how cartels launder billions of dollars each year — including by funneling cash through remittance companies like Western Union ($WU) and Remitly ($RELY).

“It’s an open secret,” they said.

Here’s how the scheme allegedly works: Cartels smuggle drugs into the U.S. Dealers sell drugs for cash. They distribute that cash to thousands of people in the U.S., who take the money to remittance companies and transfer it to Mexico in sums too small to attract attention. Contacts in Mexico receive the transfer, which is now clean money. Cartel operatives retrieve the cash.

The intermediaries get a cut — 3% to 5%, according to an investigation by the 501(c)(3) nonprofit InSight Crime, which mirrored the investor’s claims and cited Remitly as a payment system used by these “‘money-mule’ networks.”

“It’s an open secret”

Now, with cartels officially designated terrorist organizations under the Trump administration, remittance companies — which facilitate tens of billions of dollars in cross-border transfers every year — face growing scrutiny and severe risks.

If linked to cartel money laundering, these financial networks could be subject to sanctions, asset seizures, and stricter federal oversight, potentially compromising the entire industry.

On February 20, Secretary of State Marco Rubio — who had just restricted remittances to Cuba on January 31 — announced that eight cartel organizations would receive terrorist designations.

As a result of the terrorist designation, financial institutions can face serious legal ramifications if they process transactions linked to a cartel. Transfers can be delayed or blocked under the anti-terrorism provisions of the Patriot Act. These regulations significantly increase the burdens of anti-money laundering (AML) and know your customer (KYC) compliance — and substantially raise the consequences of any violation. “All property and interests in property of those designated today that are in the United States or that are in possession or control of a U.S. person are blocked, and U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions with them,” explained the State Department. Reuters echoed this statement, reporting that the “terrorist label for cartels raises prosecution risks for companies,” making them “subject to prosecution for material support of a terrorist group under the U.S. criminal code.”

“Cartel activity in the U.S. is not sicarios. It’s bankers, businessmen, and money laundering,” Stefano Ritondale, chief intelligence officer of the AI company Artorias, told Hunterbrook Media. “A multibillion industry that would be on the Dow Jones.”

Ritondale is a military intelligence veteran and runs @All_Source_News, a widely-followed X account focused on cartel violence and the drug trade.

“Willful ignorance is not necessarily a valid defense,” he noted. “Especially for remittances.”

Companies caught conducting business with terrorists have faced massive penalties. In 2022, the French industrial conglomerate Lafarge paid $778 million for facilitating terrorist payments, according to the U.S. Justice Department. Years earlier, HSBC paid $1.9 billion for allowing drug money to be laundered through the bank’s accounts, according to The Guardian.

Could remittance platforms be next?

On March 11, the Treasury Department’s FinCEN announced it would increase the scrutiny of cross-border money transmitters — requiring them to report all transactions of greater than $200. The previous threshold was $10,000.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said the policy was grounded in “deep concern with the significant risk to the U.S. financial system of the cartels, drug traffickers, and other criminal actors along the Southwest border.”

“Cartel activity in the U.S. is not sicarios. It’s bankers, businessmen, and money laundering.”

For now, the policy is targeted — focusing on businesses located in 30 zip codes across California and Texas — but could mark the beginning of a crackdown on the industry, which may present challenges for companies like Remitly, which receives “substantially all our revenue” from “digital cross-border remittances.”

It is unclear how much of that revenue is tied to organized crime. Remitly did not answer repeated requests for comment. But in a statement to Congress, its CEO noted that “in addition to being subject to our own Know Your Customer process that independently verifies the customer’s identity with high confidence, our customers have also already been identified and verified by a U.S. bank or credit card issuer.”

Remittance platforms do not, however, have visibility into everyone who ends up with the money on the other side of each transaction. And a Hunterbrook investigation revealed that Remitly’s top banking partner in Mexico, its largest market, has been repeatedly linked to cartels.

This could be a hook for the Trump administration, whose leaders — including Vice President Vance, Secretary of State Rubio, Treasury Secretary Bessent, Attorney General Pam Bondi, and President Trump himself — are focusing on remittance networks linked to cartel financing.

While studies and news reports have unearthed substantial evidence that cartels use remittances, the vast majority of remittances sent from the U.S. to Mexico are not implicated.

Many of the proposed policies aimed at combating illicit cartel finance — including transaction limits and remittance taxes — would burden people in the U.S. who are sending money home, often to their families.

These customers would also be impacted if remittance companies were to raise their fees to pass compliance costs along to customers, or to decide to leave the Mexican market entirely, leaving people with fewer legal ways to transfer funds.

“People who barely scrape by and try to send money home, if they have to show IDs, and companies take their commissions, then it is extra punitive to add more taxes, more tariffs, in the supposed effort to fight the cartels and fentanyl,” Ricardo, a former kindergarten teacher and U.S. Navy veteran who has sent remittances to Mexico for 30 years, told Hunterbrook Media. “These people are not the culprit.”

And there is indication that the regulatory focus on remittances is not only about cartels, but targeting ordinary workers as a part of a more general plan to crack down on immigration. At least one state evaluating remittance legislation — Florida — has made this purpose explicit.

Remitly: A “Disruptor” That Ended Up Charging Immigrants More Than Competitors

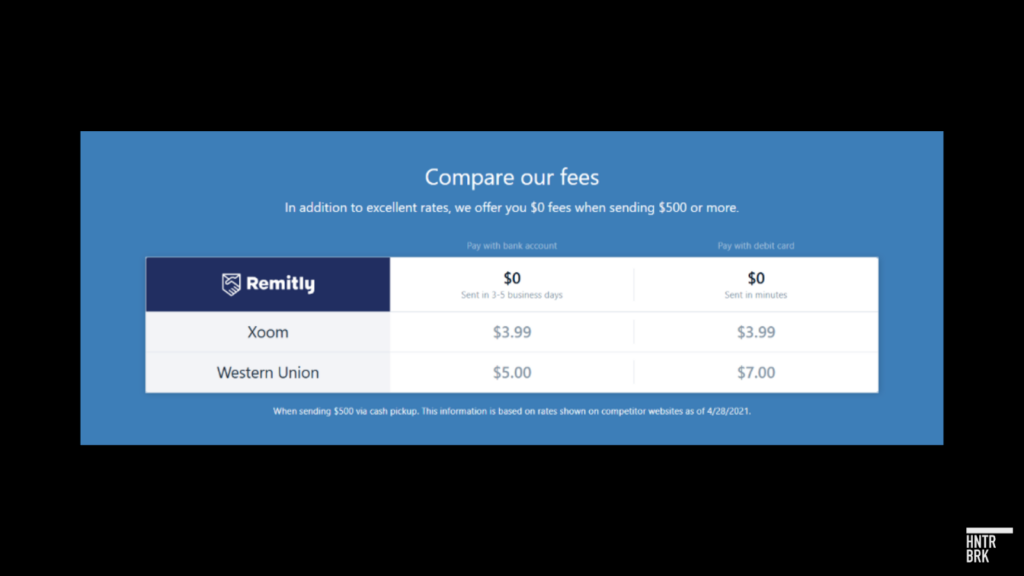

Remitly, which now claims to serve over 7.8 million active customers across 170 countries, built its brand by promising to “disrupt” the sector, taking on legacy players its CEO criticized for predatory pricing. While Western Union typically charged around 8% for transfers to countries like Mexico, Remitly initially undercut incumbents with fees as low as 2%.

In a statement to Congress, CEO Matt Oppenheimer said: “We have cut the cost of service by more than half — from 8 to 10% to under 2% — putting hard-earned money back into customers’ pockets while delivering a better overall user experience.”

Remitly’s website used to boast this fact, prominently displaying side-by-side comparisons with the fees and rates charged by competitors.

Those comparisons are now gone.

Source: Remitly-advertised rates on its “send money to Mexico” page in 2021. Remitly later deleted the comparison.

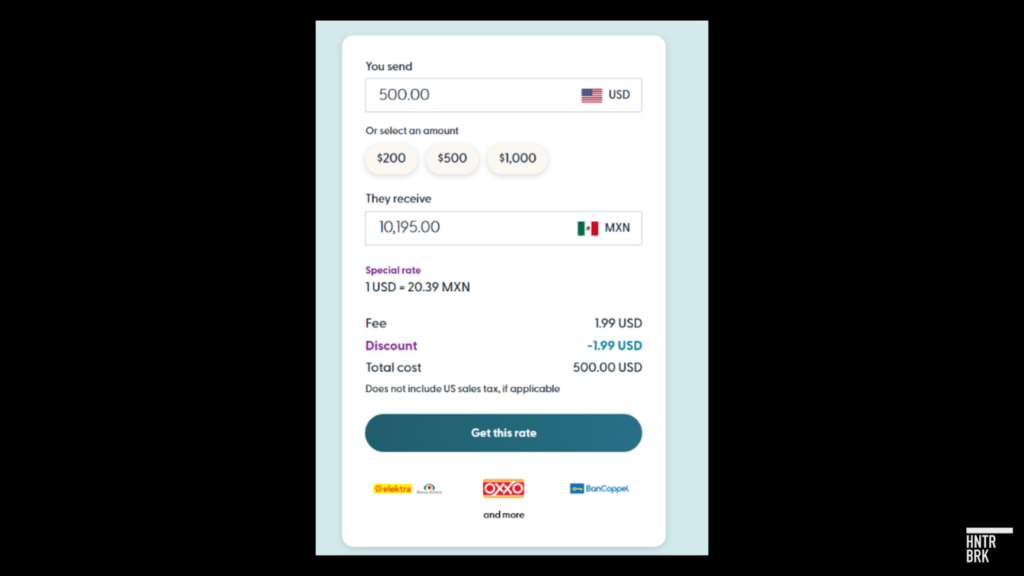

Source: Remitly-advertised rates on its “send money to Mexico” page in March 2025.

Remitly’s pricing practices have now drawn official criticism from Mexico’s consumer protection agency. In March 2024, PROFECO (Procuraduría Federal del Consumidor), Mexico’s equivalent of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, published an official report exposing Remitly as the worst-value remittance provider in the Mexican market.

In a March 2024 report titled “Who is Who in Money Transfers” (Quién es Quién en el Envío de Dinero), PROFECO provided a detailed comparison of remittance services. The government agency’s findings were unambiguous, stating:

“Remitly, la que pagó menos, tanto en envío en efectivo como en depósito a cuenta.” (Translation: “Remitly paid the least, both for cash transfers and account deposits.”)

The study compared providers based on a standard $350 USD remittance and found that Remitly delivered the lowest total amount to recipients. According to PROFECO’s official press release: “The one that paid the least was Remitly (5,671.10 pesos), with a $3.99 commission fee and an exchange rate of 16.39 pesos.”

For comparison, the top-ranked provider (ULINK) delivered 6,160.00 pesos for the same $350 transfer — nearly 8.6% more money reaching the recipient.

PROFECO’s Federal Consumer Prosecutor emphasized a crucial point for consumers: while remittance companies often advertise low commission fees, their exchange rates can significantly reduce the actual amount received. This aligned with Remitly’s strategy—while their commission was comparable to competitors, their exchange rate (16.39 pesos per dollar) was substantially worse than the top provider’s rate (17.60 pesos per dollar).

Dr. David Aguilar Romero, who served as head of PROFECO at the time of the study, presented these findings publicly in February 2024. His comprehensive analysis placed Remitly last in both major service categories—cash transfers and bank account deposits.

“We must always consider the exchange rate and commission fees when determining the best way to send money,” he said, in Spanish.

A later, December 2024 analysis, found that Remitly still had the worst exchange rate, but charged less in fees than a couple competitors.

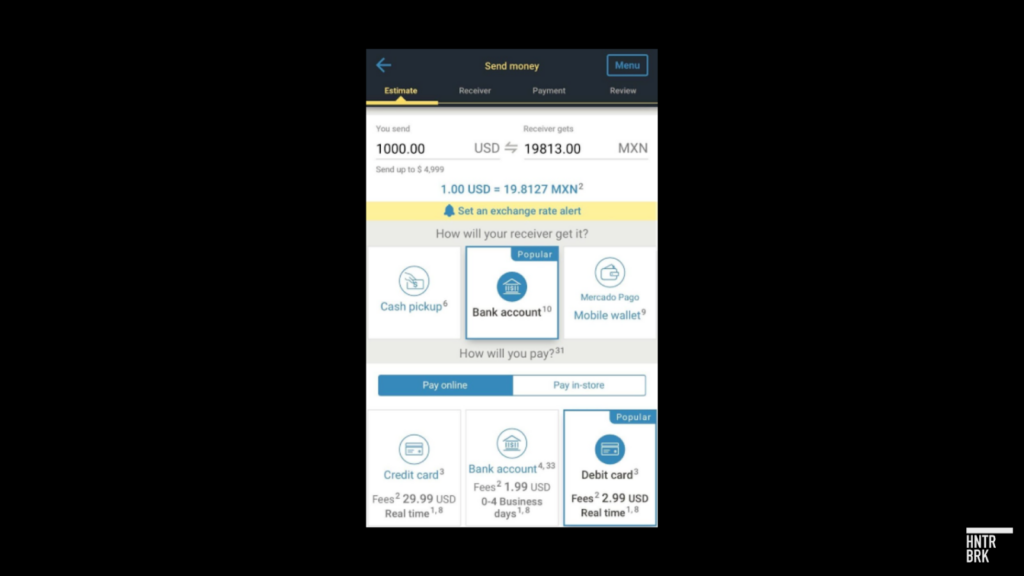

Ricardo walked Hunterbrook through what this process looks like from a consumer’s perspective — focusing on the Western Union user experience. Ricardo would pay $2.99 to send money to Mexico by debit card, plus $18.61 in currency conversion based on the exchange rate on March 12. So he’d send $1002.99, and the recipient would receive $981.39, a 2.15% rake. He does not use Remitly.

Source: Western Union screenshot shared by Ricardo, a former kindergarten teacher and U.S. Navy veteran, who said he has sent remittances to Mexico for 30 years.

The Conglomerate Remitly and Western Union Rely On

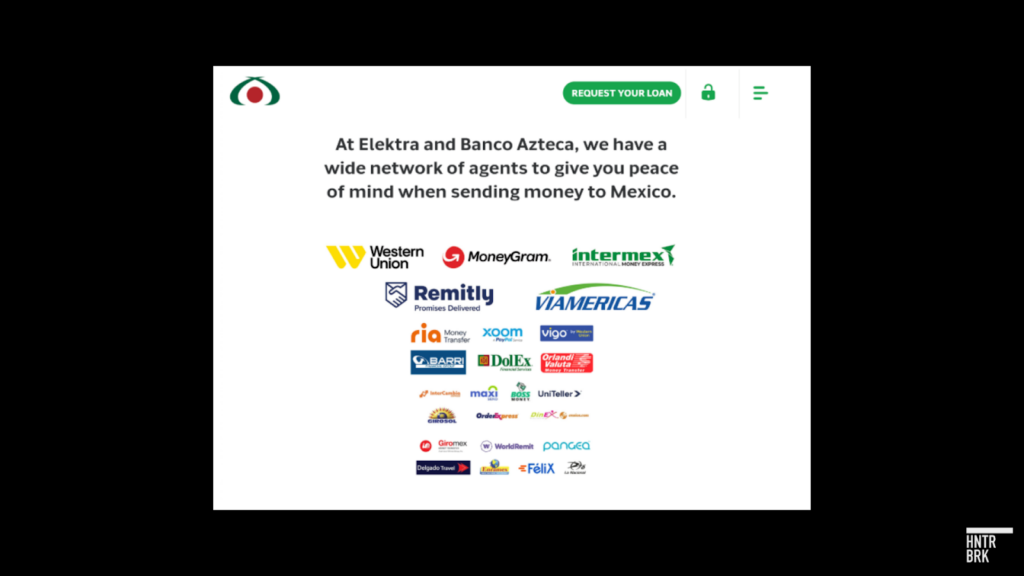

Banco Azteca and Elektra retail stores are part of Grupo Elektra, a vast financial and retail network in Mexico — one that certain reports have mentioned as providing services that criminal organizations have used, among others, to move money.

Source: Remitly list of partners in Mexico.

In 2023, Reuters referenced Grupo Elektra in its Special Report: “How Mexican narcos use remittances to wire U.S. drug profits home.”

“Reuters saw at least five people on motorcycles, wearing fanny packs and accompanied by bodyguards, collecting cash from people exiting branches of Banco Azteca, Banorte and BanCoppel … Six locals told Reuters these couriers worked for the Sinaloa Cartel picking up drug money sent as remittances.”

This reporting followed an earlier Reuters investigation on kidnapping, which noted that “most abductors ask for the money to be sent to retail bank Banco Azteca.”

An investigation by Univision and a report by the Yale Journal of International Affairs also identified Grupo Elektra and Banco Azteca, respectively, as providing services that have been exploited by money launderers.

Neither Grupo Elektra nor Banco Azteca responded to Hunterbrook’s requests for comment prior to the original publication.

After the article was published, the companies sent Hunterbrook a “formal rebuttal,” stating: “Neither Grupo Elektra nor Banco Azteca are associated with organized crime, nor do we facilitate money laundering or illicit activities.”

The companies further pointed to their “robust Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Terrorism Financing (CFT) compliance programs, which have been rigorously developed and continuously strengthened for over a decade,” saying these “programs have undergone extensive review by specialized U.S. and Mexican regulatory firms, demonstrating our unwavering commitment to financial integrity.”

“Every transaction we process is fully identified, aggregated, risk-assessed, and compliant with reporting obligations to Mexican authorities, just as our U.S. counterparts comply with the Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) obligations.”

The company has received scrutiny for other reasons as well. In 2024, a grand jury indicted Democratic congressman Henry Cuellar for money laundering, bribery, and conspiracy due to his relationship with Banco Azteca and a company in Azerbaijan, according to the Department of Justice. “Bribery case against US lawmaker implicates Mexico’s Azteca,” reported Bloomberg.

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that a bank led by Eric Hovde, then a Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, received $26.2 million in cash flown into Wisconsin by Banco Azteca. A Democratic spokesperson described this as “‘extraordinarily concerning.'”

In its statement to Hunterbrook, the bank also denied this reporting. “As we already replied to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s malicious reporting and misleading claims, this transaction pertained to the repatriation of U.S. dollars within the Mexican financial system—a legal and transparent process conducted with complete regulatory oversight on both sides of the border. Moreover, neither Grupo Elektra, Banco Azteca, nor its executives, shareholders, or board members are part of the indictment related to the ongoing Texas investigation.”

Elektra’s troubles have extended beyond these allegations to questions, with its stock plummeting by over 75% in 2024. The freefall drove litigation by investors including Astor Asset Management, a Chicago firm that has filed counterclaims against Banco Azteca, Grupo Elektra, and chairman Salinas.

In its statement to Hunterbrook, Banco Azteca pushed back on these allegations, arguing that Astor Asset Management is “an entity led and sponsored by a convicted fraudster in the U.S. and other countries, Vladimir ‘Val’ Sklarov, who has engaged in illegal financial activities, including the unauthorized sale of collateral shares.”

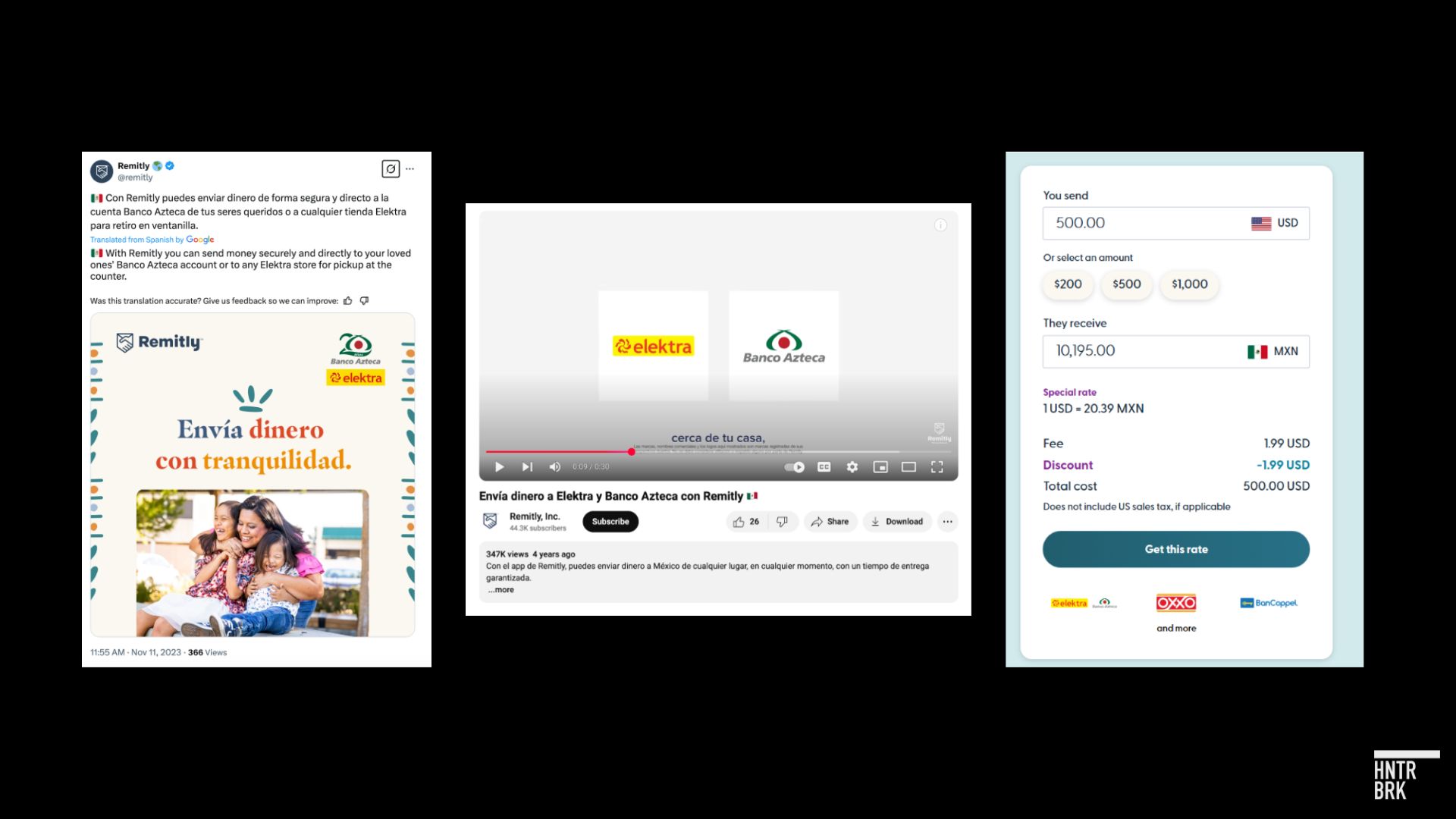

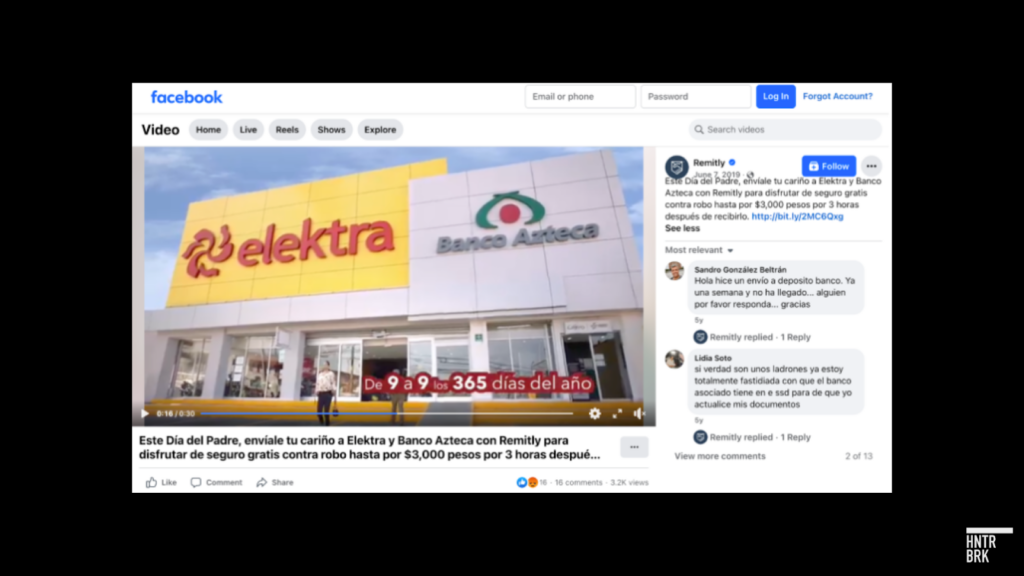

Remitly Has Highlighted Banco Azteca and Grupo Elektra for Years

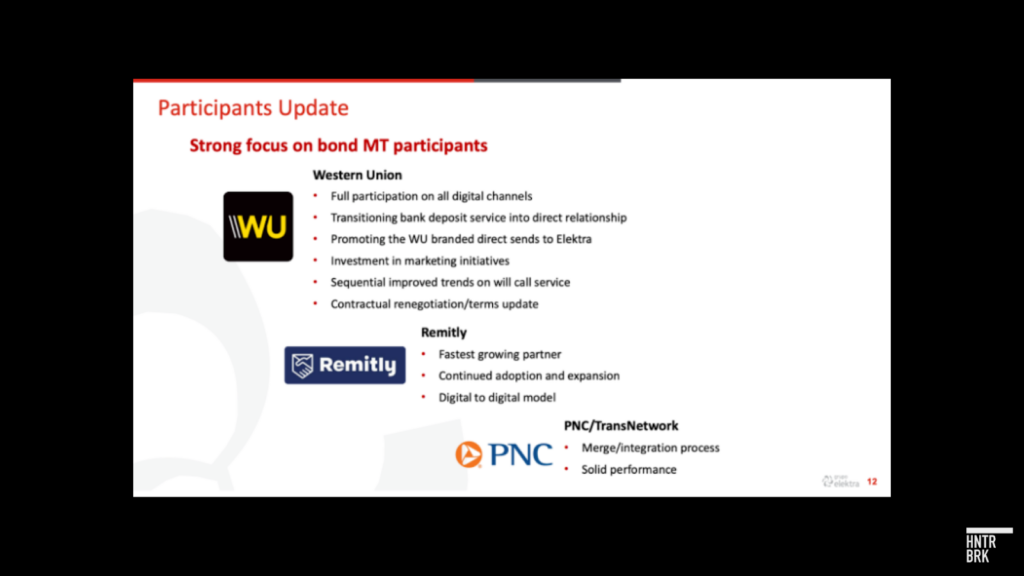

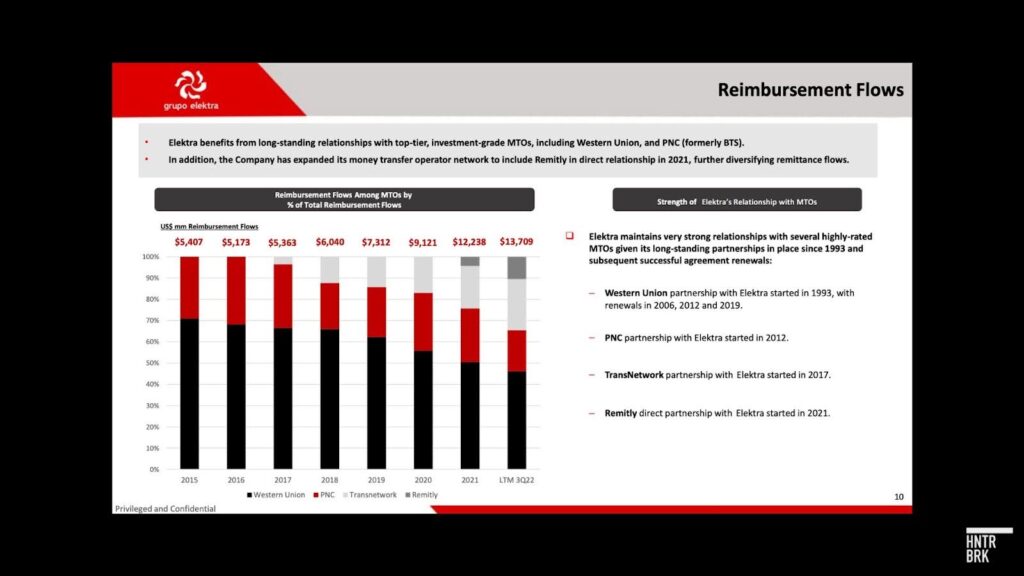

The partnership between Remitly and Banco Azteca/Grupo Elektra dates back several years and has been touted by the companies as a strength. In a 2024 presentation, Grupo Elektra called Remitly its “fastest growing partner,” showing Remitly taking market share from Western Union since 2021, when Elektra’s “direct partnership” with Remitly began.

Source: Grupo Elektra corporate presentation

Source: Grupo Elektra corporate presentation

Grupo Elektra holds “more than 40% share of the money transfers paid in Mexico,” according to S&P Global.

Source: Remitly.com FAQ

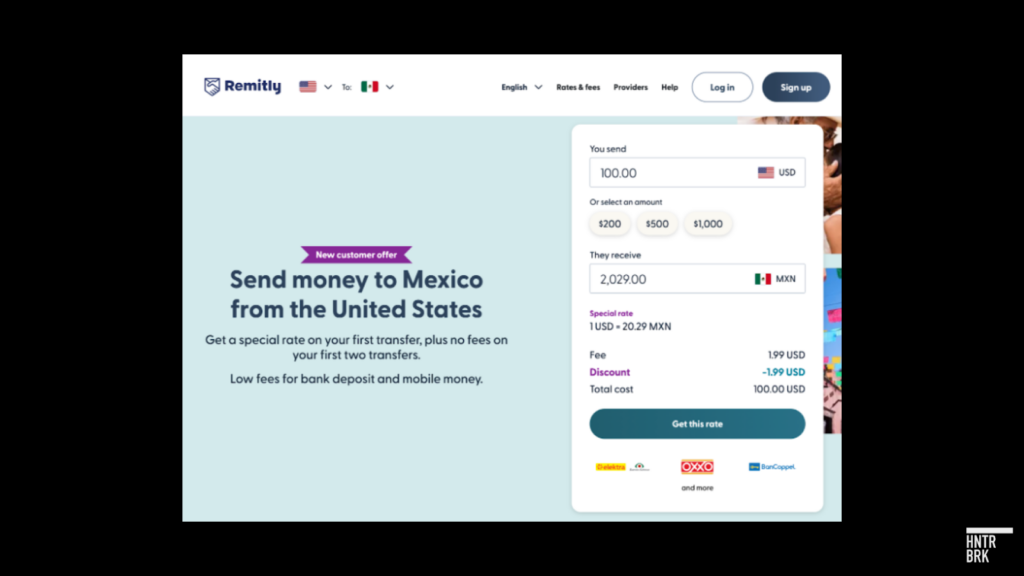

A “new customer” offer by Remitly features Elektra/Banco Azteca alongside two other banks, including BanCoppel.

Source: Remitly.com, featuring Elektra/Azteca, Oxxo, and BanCoppel in the bottom right corner.

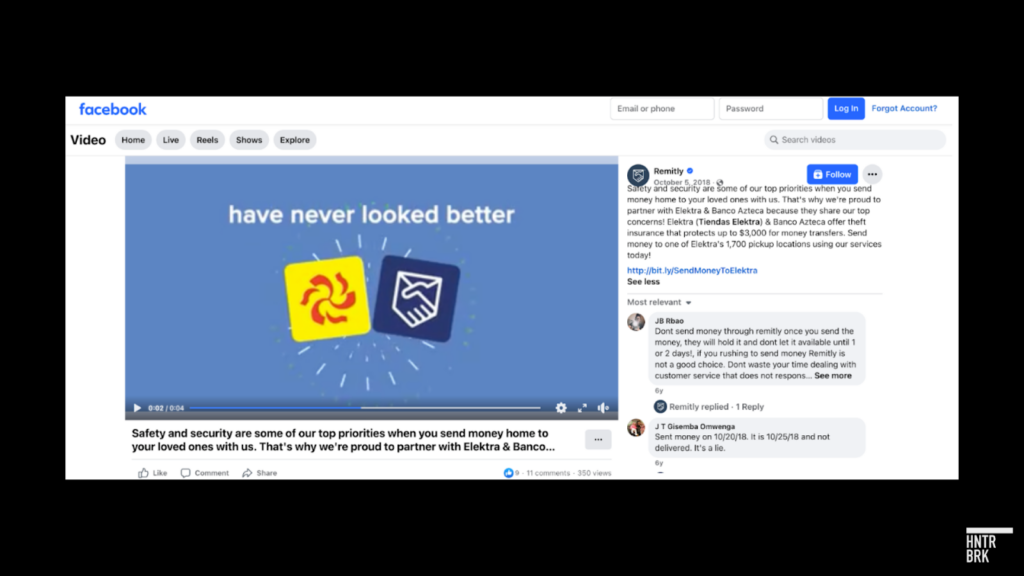

Elektra, Banco Azteca, BanCoppel and OXXO are prominently featured by Remitly’s social media as well.

Remitly’s Role in the Fentanyl Supply Chain

Remitly is also being used as a payment tool for illegal narcotics. Last year, Solana County Public Health put out a bulletin on opioid death prevention, noting that “sales can be made secretly, via online payment apps like Venmo, Zelle, Cash App and Remitly.”

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has noted that after potential buyers respond to drug traffickers’ advertisements, a payment request is often sent “using one-click apps like Venmo, Zelle, Cash App, and Remitly.”

“The darker side of Mexico’s $63bn remittances boom: Suspicions are growing that drug traffickers, as well as hard-working migrants, are sending money home,” wrote the Latin America editor at The Financial Times.

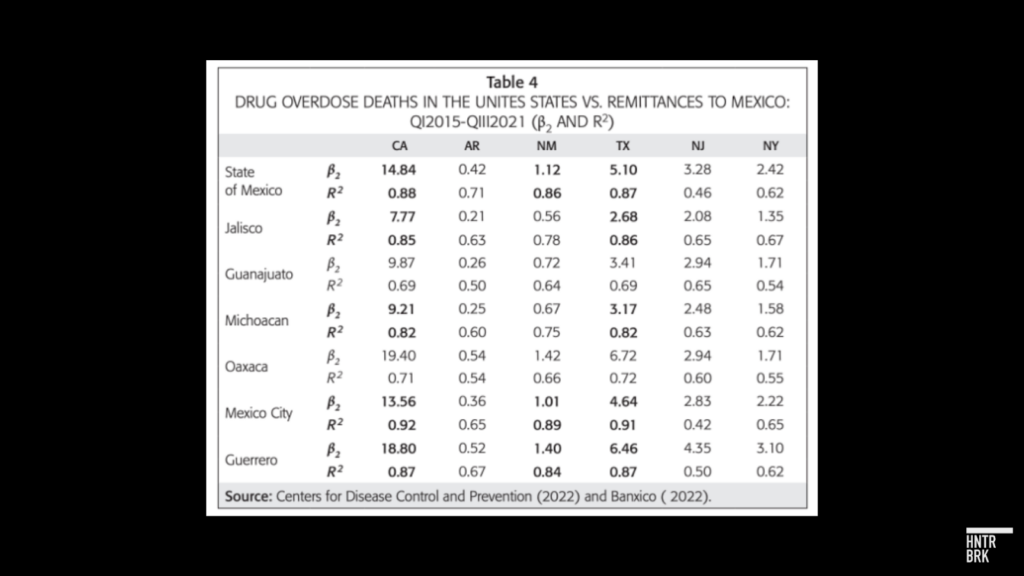

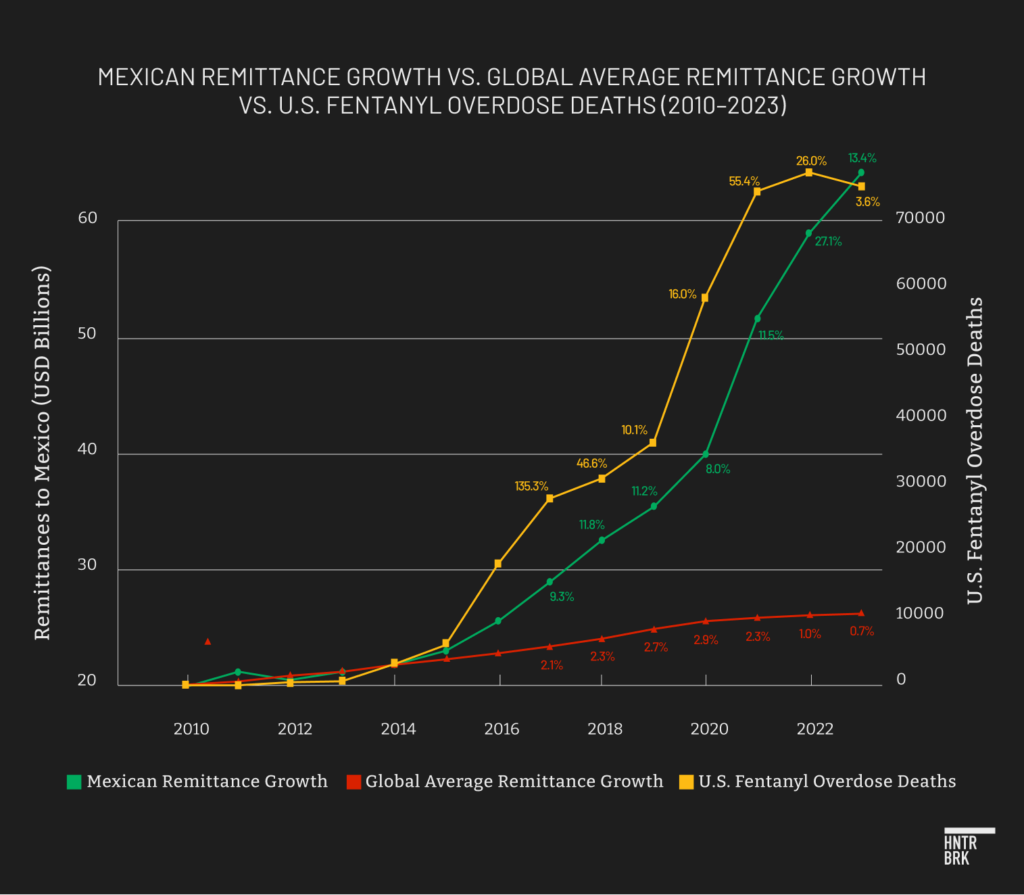

A 2023 peer-reviewed study published in the academic journal Norteamérica offers statistical evidence supporting the connection between remittances and narcotrafficking proceeds. The paper — “Mexico: Remittances, Organized Crime and U.S. Drug Overdose Crisis in Borderlands (2015-2021)” — examined the anomalous spike in remittances to Mexico during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We traced the tendency of three variables,” Gerardo Reyes Guzman, a co-author of the study and former professor at Universidad de la Salle Bajío, told Hunterbrook, referring to remittances, murders related to organized crime, and overdose deaths in the United States. “These three variables were spiking at the same time.”

The study’s methodology revealed particularly strong statistical correlations (R² values exceeding 0.80) between drug overdose deaths in U.S. border states and remittances to specific Mexican states with entrenched cartel presence.

The researchers propose a logical explanation for this phenomenon: COVID-19 border restrictions severely disrupted traditional money laundering methods. With physical cash smuggling routes constrained by pandemic border controls, cartels likely intensified their use of remittance services to move drug proceeds.

This was echoed by the FT: “Mexico’s flourishing drug cartels switched during the pandemic to sending money home disguised as remittances because border closures prevented the traditional method of smuggling back cash in vehicles.”

Guzman told Hunterbrook that before the pandemic, “the average remittances per person were about $300 to $400 monthly,” but in border states like California, Arizona, and New Mexico, “They jumped from $400-$500 to $1200-$1300 in a very short time.”

This shift coincided with another critical trend — synthetic drug trafficking surged during the pandemic, with fentanyl-related overdose deaths in the U.S. reaching unprecedented levels. According to DEA data cited in the study, “fentanyl reports to the National Forensic Laboratory Information System increased 18 times, from 5,541 in 2014 to 100,378, in 2019.” The researchers found that “drug overdose deaths and remittances behave similarly,” with both metrics accelerating dramatically after 2015 and spiking during the pandemic period.

Source: Hunterbrook recreation of data analysis based on Statista, the Baker Center for the U.S. and Mexico, CSIS, USA Facts, and the CDC. Mexican remittance growth has since slowed going into 2025, according to the Bank of Mexico.

The Trump Administration Has Remittances in Their Sights

Under the second Trump administration, led by a president who has been a longtime critic of remittances, Remitly and Western Union are facing a tough audience.

The Treasury Department’s March 11 announcement that remittance companies operating in certain geographic locations would now have to report any transfers above $200 to FinCEN (down from $10,000) is a potential harbinger of sector-wide requirements. The companies must also verify the identities of remittance senders.

“This action is being taken in furtherance of Treasury’s efforts to combat illicit finance by drug cartels,” wrote Andrea Gacki, director of FinCEN. “The Covered Business, and any of its officers, directors, employees, and agents, may be liable, without limitation, for civil or criminal penalties for violating any of the terms of this Order.”

In 2023, then-Senator Vance introduced the Withholding Illegal Revenue Entering Drug Markets (WIRED) Act, seeking to “tax cartel’s international money transfers.” The law would not only tax cartel-related transfers, but every transfer by noncitizens out of the U.S., essentially making it a tax targeted on any noncitizens sending money home.

Texas Sen. John Cornyn, who now heads the U.S. Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, introduced a bill targeting remittances in 2019 — with the stated purpose of preventing “the use of remittances by certain individuals and crime syndicates for purposes of financing terrorism, narcotics trafficking, human trafficking, money laundering, and other forms of illicit financing.” Similar restrictions were included in an anti-money laundering package introduced by now-Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley.

Trump’s new National Security Advisor, former Congressman Mike Waltz, co-sponsored a 2023 bill to authorize military force against Mexican drug cartels. Attorney General Bondi announced that Justice Department prosecutors will prioritize cartel cases.

And in March, the Stop Fentanyl Money Laundering Act of 2025 may reach the House floor, after unanimously advancing from committee 49-to-0 with bipartisan support in February. The Act mandates that the Treasury Department will strengthen regulations on domestic financial institutions, including remittance providers, within 180 days, which could significantly increase compliance costs for companies like Remitly and Western Union.

At the state level, Oklahoma has imposed a $5 fee on transfers under $500 and a 1% remittance tax above $500. Florida, Ohio, Alabama, Utah, and Pennsylvania are reportedly evaluating similar proposals. Arizona is considering a 30% remittance tax.

These policies are being encouraged by conservative think tanks like the America First Policy Institute and the Heritage Foundation, which also seek to weaponize remittance burdens against immigrants.

The AFPI wrote: “Narcotic trafficking networks typically use international wire transfers to send money out of the country. Trafficking networks favor international wire transfers because these companies lack the oversight of traditional banks, making it easier to structure the transactions to hide their illicit nature.”

The Heritage Foundation proposed that states “prevent or tax remittances sent abroad” as a way to prevent illegal immigration, which appear to see remittances as a leverage point to wield as part of their broader anti-immigrant agenda.

And in the 2025 reconciliation package, the House Freedom Caucus and Republican Congressman Chip Roy proposed a remittance tax.

“People who barely scrape by and try to send money home, if they have to show IDs, and companies take their commissions, then it is extra punitive to add more taxes, more tariffs, in the supposed effort to fight the cartels and fentanyl,” a former kindergarten teacher and U.S. Navy veteran who has sent remittances to Mexico for 30 years told Hunterbrook Media. “These people are not the culprit.”

Against this tightening regulatory backdrop, the growth in remittances to Mexico has already decelerated. After surging 25.9% in 2021, remittances growth declined to 12.1% in 2022, 7.6% in 2023, and only 2.3% in 2024. For January 2025, the most recent month reported by the Bank of Mexico, growth fell 11% from December 2024, alongside smaller average transfer size.

Western Union’s CEO told investors on March 11 the remittance company has seen a “slowdown in our Latin America business” and guided lower for 1Q25, blaming “anxiety in the marketplace post-election.”

The Threat of Competition

Beyond the growing legal risks, Remitly, Western Union, and their private equity-owned peer MoneyGram also face several competitive threats.

Visa Direct enables instant, direct-to-card money transfers, lowering transaction costs. Another challenger is crypto, with financial technology companies like Coinbase and Robinhood offering transfers. Stablecoins like Tether and Circle are also on the rise, with Stripe and Bank of America evaluating transfer services. And then there’s Zelle, Venmo, and Cash App.

“Stretched valuation makes the stock highly sensitive to any revenue slowdown. Even minor deceleration could trigger sharp multiple compression,” wrote an investment director who covers Mexico at a global investment manager. “Slowing revenue growth could significantly impact profitability due to the company’s heavy spending on marketing and R&D. As operating deleverage sets in, profitability could quickly plummet, leading to a sharp negative impact on the stock price.”

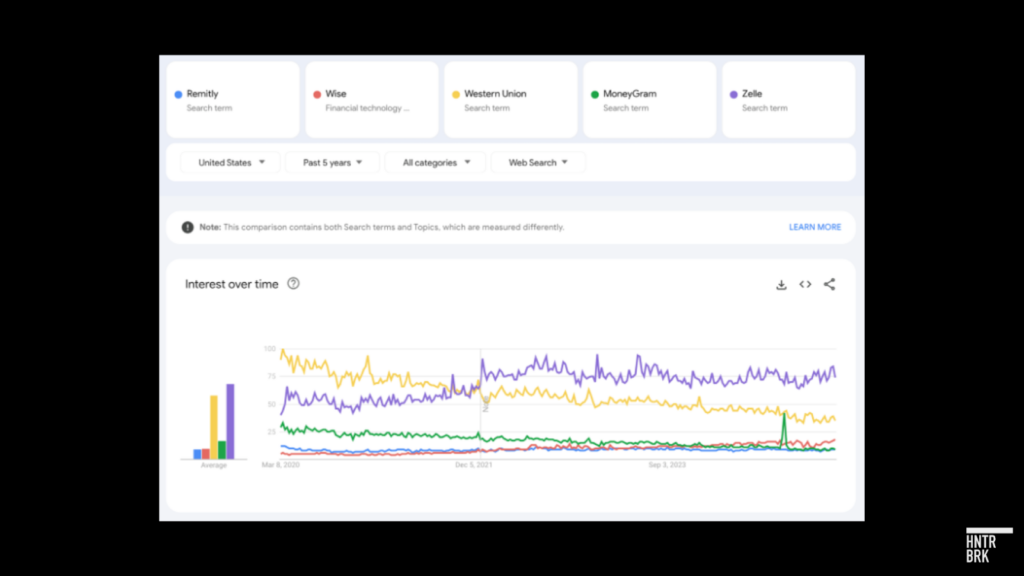

Interest in the company has also fallen relative to peers, according to Google Trend data.

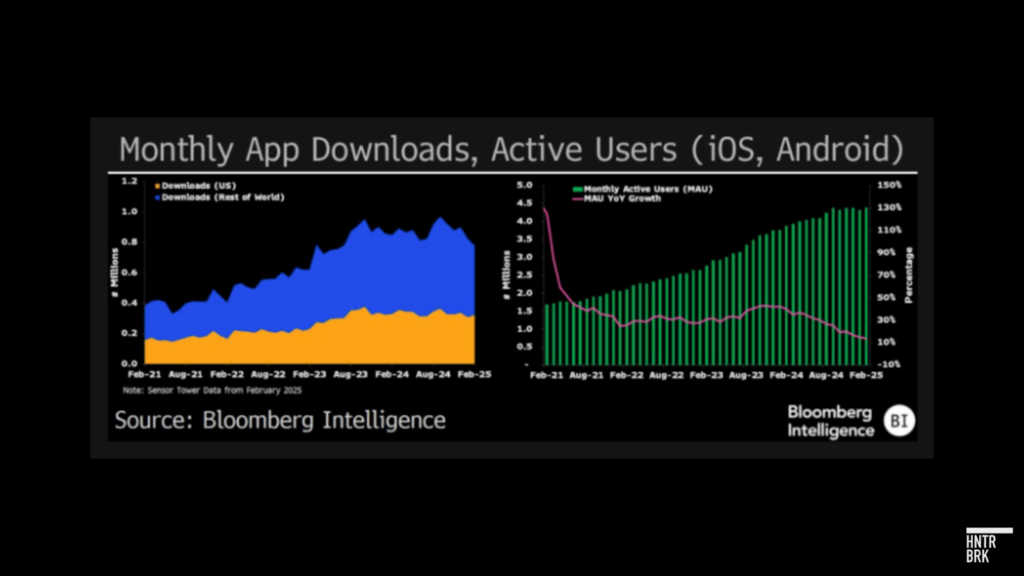

Remitly’s app has also seen declining growth, according to data from Sensor Tower reported on by Bloomberg — which revealed an 8% drop in downloads since last year, despite a 13% increase in monthly active users

Source: Bloomberg, data for Remitly

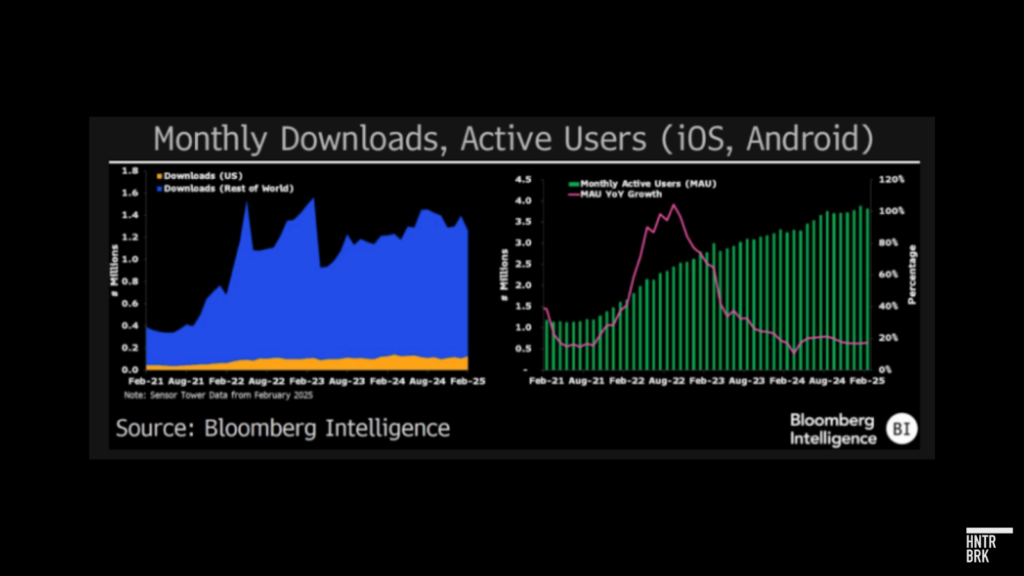

Wise (formerly TransferWise), by contrast, has seen its downloads continue to grow — while Western Union has seen its usage decline.

Source: Bloomberg, data for Wise

Source: Bloomberg, data for Western Union

Barclays, which covers Remitly in its sell-side analyst coverage, highlighted Remitly’s potential to regain an accelerated growth trajectory in a February report, but added: “We note that the FY25 outlook assumes no changes in macro or political conditions, and the company sounded confident on the call regarding the ability to remain resilient vs. any macro/regulatory changes.”

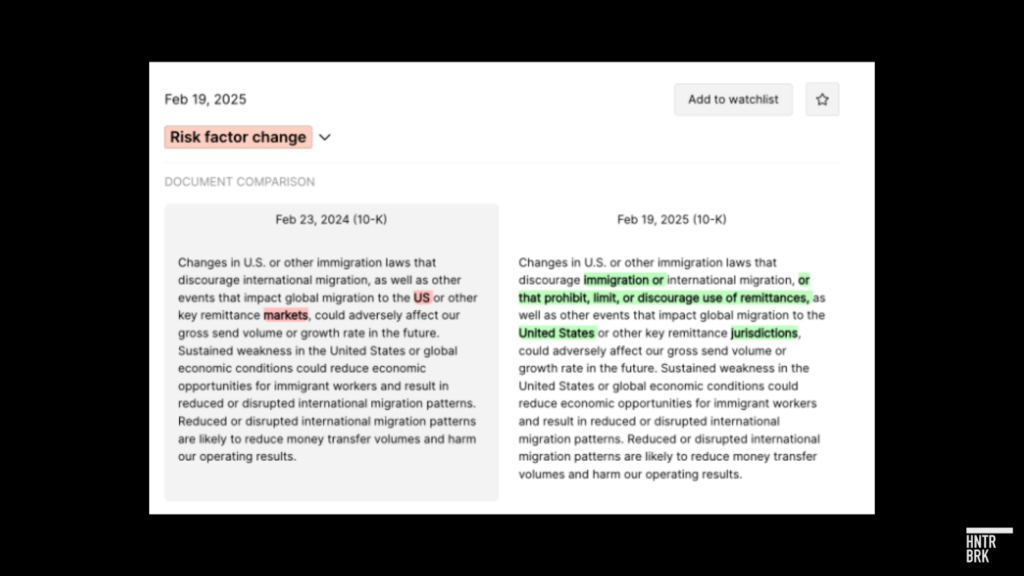

Remitly, however, is clearly aware of the risk posed by the change in administration, based on updated risk factor language in its 10-K:

Source: Canary Data

The company has also experienced turnover related to its accounting. Its CFO and EVP, head of customer and culture departed in 2024, following material weaknesses in SEC filings the prior year. Its chief accounting officer left at the start of 2025.

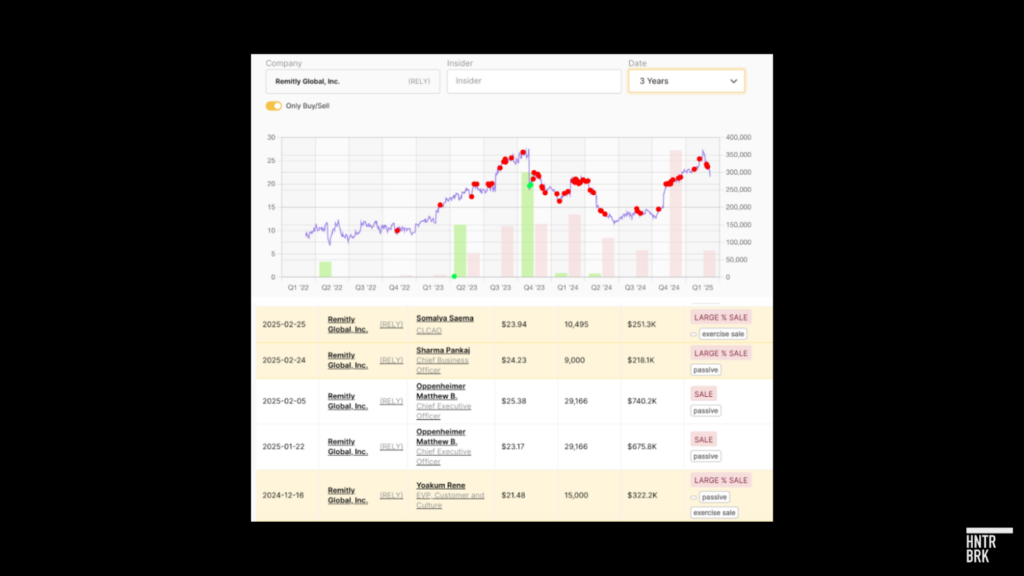

Remitly’s remaining executives do not appear bullish either, with several executives selling stock through 2024 and into 2025. As investment fund Spruce Point Management noted in a short report on Remitly posted March 11, Remitly’s co-founders — including its CEO and former COO — and CBO have each initiated substantial stock sales. Spruce Point also criticized Remitly for its accounting, false marketing, and other misrepresentations.

Source: Canary Data

Silence From the Remittance Companies

Remitly, Western Union, and MoneyGram did not reply to repeated requests for comment about cartel activity on their platforms or efforts to limit it.

Months after the Mexican investor told Hunterbrook about this “open secret” as the chartered jet hummed over the U.S. — now with the new administration cracking down, investigators detailing the scheme, and several outlets reporting on remittance risks — it’s no secret at all.

Authors

Nathaniel Horwitz is CEO of Hunterbrook. He has contributed to The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, The Harvard Crimson, The New York Times, and The Australian Financial Review. He co-founded, invested in, and served on the boards of several biotechnology companies, ranging from AI-designed medicines for cancer to cell therapies for autoimmune diseases. He has a BA in Molecular Biology from Harvard, where he coauthored biomedical research in the scientific journal Cell. His first job out of high school was reporting for his hometown newspaper. He volunteers as executive chair of the 501(c)(3) education nonprofit Mayday Health.

Till Daldrup joined Hunterbrook from The Wall Street Journal, where he focused on open-source investigations and content verification. In 2023, he was part of a team of reporters who won a Gerald Loeb Award for an investigation that revealed how Russia is stealing grain from occupied parts of Ukraine. He has an M.A. in Journalism from New York University and a B.S. in Social Sciences from University of Cologne. He’s also an alum of the Cologne School of Journalism (Kölner Journalistenschule). Till is based in New York.

Blake Spendley joined Hunterbrook from the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), where he led investigations as a Research Specialist for the Marine Corps and US Navy. He built and owns the leading open-source intelligence (OSINT) account on X/Twitter, called @OSINTTechnical (>925K followers), which now distributes Hunterbrook Media content. His OSINT research has been published in Bloomberg, the Wall Street Journal, and The Economist, among other top business outlets. He has a BA in Political Science from USC.

Jack Scullion is a political researcher who has worked on Senate, gubernatorial, and House campaigns across the United States. His investigative work has covered one of the country’s largest financial firms, a large municipal police department, and reproductive rights issues.

Editor

Jim Impoco is the award-winning former editor-in-chief of Newsweek who returned the publication to print in 2014. Before that, he was executive editor at Thomson Reuters Digital, Sunday Business Editor at The New York Times, and Assistant Managing Editor at Fortune. Jim, who started his journalism career as a Tokyo-based reporter for The Associated Press and U.S. News & World Report, has a Master’s in Chinese and Japanese History from the University of California at Berkeley.

Hunterbrook Media publishes investigative and global reporting — with no ads or paywalls. When articles do not include Material Non-Public Information (MNPI), or “insider info,” they may be provided to our affiliate Hunterbrook Capital, an investment firm which may take financial positions based on our reporting. Subscribe here. Learn more here.

Please contact ideas@hntrbrk.com to share ideas, talent@hntrbrk.com for work opportunities, and press@hntrbrk.com for media inquiries.

LEGAL DISCLAIMER

© 2025 by Hunterbrook Media LLC. When using this website, you acknowledge and accept that such usage is solely at your own discretion and risk. Hunterbrook Media LLC, along with any associated entities, shall not be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of information provided in any Hunterbrook publications. It is crucial for you to conduct your own research and seek advice from qualified financial, legal, and tax professionals before making any investment decisions based on information obtained from Hunterbrook Media LLC. The content provided by Hunterbrook Media LLC does not constitute an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to purchase any securities. Furthermore, no securities shall be offered or sold in any jurisdiction where such activities would be contrary to the local securities laws.

Hunterbrook Media LLC is not a registered investment advisor in the United States or any other jurisdiction. We strive to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided, drawing on sources believed to be trustworthy. Nevertheless, this information is provided "as is" without any guarantee of accuracy, timeliness, completeness, or usefulness for any particular purpose. Hunterbrook Media LLC does not guarantee the results obtained from the use of this information. All information presented are opinions based on our analyses and are subject to change without notice, and there is no commitment from Hunterbrook Media LLC to revise or update any information or opinions contained in any report or publication contained on this website. The above content, including all information and opinions presented, is intended solely for educational and information purposes only. Hunterbrook Media LLC authorizes the redistribution of these materials, in whole or in part, provided that such redistribution is for non-commercial, informational purposes only. Redistribution must include this notice and must not alter the materials. Any commercial use, alteration, or other forms of misuse of these materials are strictly prohibited without the express written approval of Hunterbrook Media LLC. Unauthorized use, alteration, or misuse of these materials may result in legal action to enforce our rights, including but not limited to seeking injunctive relief, damages, and any other remedies available under the law.